Valuing the priceless

Publicly funded museums, galleries, and heritage organisations own or are responsible for the care of many of our nation’s taonga. They are the storehouses for our memories, provide important resources for bringing local communities together, and teach our younger generation about our past.

Publicly funded museums, galleries, and heritage organisations own or are responsible for the care of many of our nation’s taonga. They are the storehouses for our memories, provide important resources for bringing local communities together, and teach our younger generation about our past.

How these organisations report on the dollar value of these heritage assets is a vexed issue, so we thought we’d explain in this blog why it’s important that they do.

Why should we put heritage assets into our financial statements?

Recognising heritage assets can help entities to meet the objectives of accountability and transparency, and help governing bodies better manage their assets. For example, if an entity wants to apply for funding to continue to care for its heritage assets, having audited accounts with values attached to heritage assets may help support a business case for additional funding.

Also, there are requirements in the accounting standards to value heritage assets and put them into the accounts. The standards that refer to heritage assets are:

- PBE IPSAS 17 Property, Plant and Equipment (applying to larger public benefit entities);

- NZ IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment (applying to larger for-profit entities); and

- PBE SFR-A (PS) Public Benefit Simple Format Reporting – Accrual (applying to smaller public benefit entities).

Aren’t heritage assets about people and culture, not money?

Some entities may argue that it is inappropriate to attach a dollar value to some cultural heritage assets. We accept that it may be wrong to put a dollar value on cultural heritage assets in some cases, which is why care needs to be exercised before deciding not to attach a dollar value to cultural heritage assets. However, a big advantage of attaching a dollar value to such assets is being able to justify the resources put into looking after them.

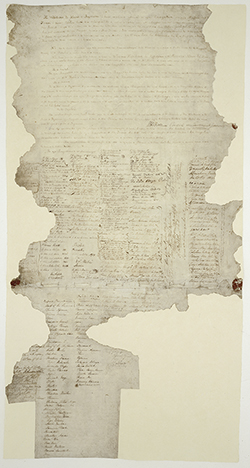

An example of a unique cultural heritage asset that has been assigned a value for accounting purposes is Te Tiriti o Waitangi – the Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty is part of the National Archives Heritage Collection and is referred to in the Department of Internal Affairs’ annual reports. Items in the National Archives Heritage Collection, including the Treaty, are valued independently at least every three years.

Do auditors know how hard it is to put a dollar value on heritage assets?

Some entities with large holdings of heritage assets – such as museums – find it a real pain to be told that they have to identify and attach a dollar value to their heritage assets for their accounts. They may say that they don’t have a lot of money to perform expensive valuations and even when they do, the dollar amount is more of a “stab in the dark” as opposed to a reliable figure. Surely museums’ time and money are better spent actually collecting and looking after heritage items?

We understand the frustrations. The accounting standards say that the value of heritage assets should be reported in the accounts, so auditors are going to ask questions. Entities can adopt the “cost model” of valuation and only perform a valuation once. The idea here is that you identify and value your heritage assets once and then treat that as “deemed cost”. You may have cost figures for heritage assets that your entity bought, but often heritage assets are given or donated to an entity, so it’s helpful for it to be valued once to establish a deemed cost. Then, after that, the heritage assets can be depreciated each year – that is, if they depreciate at all. Depreciation recognises that assets wear out, disintegrate, or become obsolescent over time. Even if assets are rising in value, they usually do depreciate.

Some heritage assets are going to be easier to put a dollar value on than others. For example, there is probably going to be an active market for art work. Some assets will be much harder to value, like a collection of dried spiders or insects. The key is to put a dollar value on all the heritage assets you can and make good written disclosures about the others in the accounts. You need to be able to show that you tried hard to value each heritage asset (or group of heritage assets) before you conclude you couldn’t do it.

How can I learn more about what is required?

If you play a part in looking after our heritage assets and have any questions, have a chat with your auditor about exactly what accounting standards apply to you and what they say. Your auditor is best placed to help you work through the detail.