Great powers, great responsibilities: Balancing competing rights in the age of Covid-19

The adage from the film Spider-Man, that “with great power comes great responsibility”, is perhaps more relevant now than ever in the age of Covid-19. With individual rights limited to an unprecedented degree – from the Level 4 lockdowns of the past to the “traffic light” restrictions of today – now is a ripe time to reflect on how we can address the “wicked problem” of balancing different and competing rights.

The adage from the film Spider-Man, that “with great power comes great responsibility”, is perhaps more relevant now than ever in the age of Covid-19. With individual rights limited to an unprecedented degree – from the Level 4 lockdowns of the past to the “traffic light” restrictions of today – now is a ripe time to reflect on how we can address the “wicked problem” of balancing different and competing rights.

Chaired by Paul James (Chief Executive, Department of Internal Affairs), the Transparency International Leaders NZ Integrity Forum focused on the tensions and trade-offs between different and competing rights. Given the significant powers held by Government to place restrictions on these rights, there also arises the critical need for Government to act with integrity.

Chief Human Rights Commissioner, Professor Paul Hunt (Chief Human Rights Commissioner) observed that many in New Zealand had a narrow understanding of human rights – one limited to the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act, sitting squarely in the realm of lawyers and courts. He emphasised that New Zealand is bound in international law to advance a wide range of human rights that extend beyond the Bill of Rights Act.

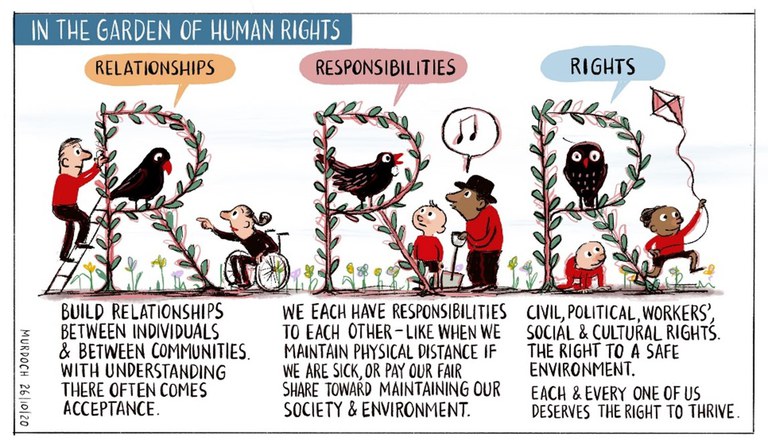

Professor Hunt presented human rights as having Relationships, Responsibilities, and Rights, consistent with both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi (te Tiriti). Rather than viewing human rights as narrowly centred on the entitlements of individuals, this approach also gives attention to the communal and collective dimensions of human rights, which are important features of both the UDHR and te Tiriti.

Professor Hunt further noted that the Bill of Rights justifies limitations on rights and freedoms to “reasonable” limits as prescribed by law in a free and democratic society. For example, recent public health measures (such as vaccine mandates) limited a number of rights (such as the rights to work and assembly). A rather narrow approach to limiting rights, then, would essentially frame these public health measures as a negative that is “bad for human rights”.

Professor Hunt argued that another approach would be to see the Government’s public health decisions as requiring a need to fairly and reasonably balance different rights. To use the previous example, this perspective would balance the rights to work and assembly with the right to access healthcare and health protection. And human rights law and practice have developed sensible criteria to help all parties strike fair, reasonable, rational, transparent, and reviewable balances between competing rights.

Perhaps most importantly, Professor Hunt highlighted that this balancing act is an ongoing exercise. As Government decision-makers during the height of pandemic could attest, we live in a world where new information and evidence emerge every day. New balances need to be struck, and restruck, by decision-makers as the operating context changes around them.

Professor Andrew Geddis (Faculty of Law, University of Otago) began by opining that the topic for discussion – the balancing of competing rights, need, and responsibilities – is essentially the task of government (across its three branches - Parliament, the Executive, and the judiciary).

Professor Geddis reflected that the Government response to Covid-19 was, by necessity, multi-faceted. On one hand, the response was a public health one, based on science, data, and evidence. At the same time, there was also a crisis of fear that demanded its own response. This crisis of fear was not only a fear of the virus, but also a fear of the expansion of state authority, and the use of coercive powers rarely seen before.

During the early stages of New Zealand’s response to the pandemic, public opinion generally converged with public health measures. The limiting of individual rights was widely accepted. As time went on, and public opinion began to splinter on whether the impact on rights was justified, public emotions and opinions challenged Government decision-making. This played out through anti-vaccine debates, legal challenges to vaccine mandates, and even protest actions on the Parliament lawn.

Despite the influence of public opinion, Professor Geddis argues that our Bill of Rights is nevertheless based on a model of rationality – a “Bill of Reasonable Rights” (quoting Professor Paul Rishworth of Auckland University). There are few rights that cannot be reasonably limited in certain circumstances. The reason and evidence-based response is what courts ultimately fall back on; an example is how court decisions responded to challenges to vaccine mandates. This poses a challenge to policymakers, who may make trade-offs on both public opinions and evidence, while courts consider the balancing of rights purely on the “Bill of Reasonable Rights”.

In Professor Geddis’ view, Government policymakers are influenced by public opinion, and their judgement can be based on emotions. While some policy decisions are more easily and obviously based on data and evidence (such as health measures to stop or slow a pandemic), others are less so (such as measures that are put in place to respond to public fear). Regardless, policymakers cannot escape from making trade-offs in making decisions to balance different rights.

As I reflected upon this session, I came back to a message that Professor Geddis raised, and we at the Office of the Auditor-General often reinforce in our work: decisions are much easier for the public to understand, and accept, if their inner workings and reasonings are made transparent. This is one way through which decision-makers can act with integrity when faced with the difficult task of balancing different, and competing, human rights for the well-being and future of New Zealand.