Part 2: Councils’ performance in 2021/22 and 2022/23

2.1

In this Part, we look at:

- the revenue reported by councils;

- the operating expenditure of councils;

- how councils are progressing with their reporting on central government funding;

- processing times for building consent applications;

- processing times for resource consent applications; and

- three waters performance measures.3

Summary of findings

2.2

As a whole, councils' total revenue has steadily increased during the past two years. Total revenue was $17.8 billion in 2022/23 (an increase of 18% since 2020/21). Much of the increase is attributed to "other income" and subsidies and grants, including government funding for recovery from severe weather events and stimulus funding for the Three Waters Reform Programme.

2.3

Councils' total operating expenditure increased by 23% during the past two financial years to $15.8 billion in 2022/23. Inflation is a key cause of this increase because councils' operating costs (for example, employee and insurance costs) and costs to maintain and build infrastructure increased.

2.4

Depreciation is increasing because higher costs of construction have resulted in higher infrastructure valuations. Rising interest rates meant that finance costs also increased during the past two years.

2.5

Performance reporting against the key metrics of building consents, resource consents, and three waters show that most councils have areas they could improve.4

2.6

Councils are still struggling to meet timeliness measures for processing building consent applications and resource consent applications. In 2022/23, only three councils processed 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame, and only 13 councils processed 100% of resource consent applications within statutory time frames.

2.7

Some councils do not report on this aspect of their performance to their communities.

2.8

For three waters, the results for 2021/22 and 2022/23 highlight that all councils should prioritise improving their performance against water supply measures. A specific concern in 2022/23 was that fewer than 60% of water supply performance measures were achieved.

Revenue reported by councils

2.9

In 2021/22, councils reported total revenue of $16.3 billion, which was 4% more than budgeted. In 2022/23, councils reported total revenue of $17.8 billion, which was 7% more than budgeted (see Figure 1).

2.10

Excluding Auckland Council, councils reported total revenue of $10.6 billion in 2021/22 (7% higher than forecast) and $11.1 billion in 2022/23 (6% higher than forecast).

Figure 1

Total reported revenue, 2018/19 to 2022/23

| Year | Total reported revenue (all councils) | Budget variance | Total reported revenue (excluding Auckland Council) | Budget variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/19 | $13.3 billion | 3% | $8.5 billion | 5% |

| 2019/20 | $13.9 billion | 2% | $8.7 billion | 3% |

| 2020/21 | $15 billion | 11% | $9.7 billion | 15% |

| 2021/22 | $16.3 billion | 4% | $10.6 billion | 7% |

| 2022/23 | $17.8 billion | 7% | $11.1 billion | 6% |

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.11

Figure 2 shows the main categories of revenue for councils from 2018/19 to 2022/23.

Figure 2

Revenue by subcategory, 2018/19 to 2022/23

| Year | Development and financial contributions | Other income | Rates | Subsidies and grants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/19 | 3.33% | 38.11% | 46.61% | 11.96% |

| 2019/20 | 2.94% | 34.92% | 47.55% | 14.59% |

| 2020/21 | 3.38% | 33.87% | 46.56% | 16.18% |

| 2021/22 | 3.25% | 37.97% | 43.83% | 14.95% |

| 2022/23 | 3.35% | 35.15% | 44.23% | 17.27% |

Note: Development contributions are contributions from developers that a council collects under the Local Government Act 2002 to help fund new infrastructure required by growth.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.12

In 2020/21, $7 billion (46.6%) of councils' total revenue was from rates. In 2021/22, $7.6 billion (43.8%) of councils' total revenue was from rates. In 2022/23, $8 billion (44.2%) of councils' total revenue was from rates. This was largely consistent with the amount of revenue that councils planned to collect from rates.

2.13

We found that other income was $1.9 billion (39%) higher than planned in 2021/22 and $1.1 billion (20%) higher than planned in 2022/23. Examples of other income include fees and charges, gains from land sales, fuel tax, gains on disposal, and new infrastructure that has been vested in councils.

2.14

Examples of other income that increased include:

- constructing more infrastructure assets than were budgeted (which then became vested assets);

- more favourable revenue from fees and charges after growth, in items such as water meter and connection fees or landfill volumes;

- fair value gains from "found" assets;5 and

- selling land.

2.15

For councils as a whole, subsidies and grants revenue was 5% less than budgeted in 2021/22. However, in 2022/23, it was 14% more than initial estimates (by comparison, it had been 16% more than expected in 2020/21).

2.16

The decrease in subsidies and grant revenue in 2021/22 was from factors such as reduced Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency (Waka Kotahi) subsidies and infrastructure projects being behind schedule (which reduced the number and value of infrastructure funding requests).

2.17

Some councils, such as Tauranga City Council and West Coast Regional Council, reported on these reductions, citing delays in their roading and infrastructure projects.

2.18

Tauranga City Council noted that Waka Kotahi had placed limits on its total operating subsidies and that capital project funding was significantly below budget because of a shortage of project managers and contractors.

2.19

Rotorua District Council reported not receiving grant revenue for capital projects because of construction delays and material shortages.

2.20

However, not all councils received reduced subsidies and grant revenue (paragraph 2.47 sets out the main sources of subsidies and grants). Some councils received more external grant funding to support their recovery from severe weather events or as a result of government stimulus funding related to three waters reform.

2.21

In 2022/23, the councils that needed additional support to respond to emergency events received the biggest boost in subsidies and grants revenue. This was particularly the case for councils affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

2.22

Some councils also received additional government grants to realise local projects. For example, Southland District Council received unbudgeted revenue to improve tourism infrastructure in Manapouri and Te Anau.

2.23

Development and financial contribution revenue has continued to increase since 2020/21, when councils received $509 million (31% higher than budgeted). In 2021/22, development and financial contribution revenue was $566 million (12% higher than budgeted). In 2022/23, it was $607 million (7% higher than budgeted).

2.24

Some districts continued to receive strong development and financial contributions during this period (such as Masterton District Council and Waimate District Council). For example, Waimate District Council's development and financial contributions were linked to a large amount of water and sewer capital contributions and subdivision growth.

2.25

Development-related revenue at Grey District Council was also significantly above what it had budgeted. This was from higher than anticipated building and subdivision activity.

2.26

Some councils introduced new development contribution polices, or amended existing ones, to help reduce the financial burden for ratepayers.

Operating expenditure of councils

2.27

In 2021/22 and 2022/23, councils' operating expenditure was higher than forecast (see Figure 3). In some instances, we consider results for councils under five different subsectors (see the Appendix).

Figure 3

Total reported operating expenditure, 2018/19 to 2022/23

| Year | Total reported operating expenditure (all councils) | Budget variance | Total reported operating expenditure (excluding Auckland council) | Budget variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/19 | $11.7 billion | 4% | $7.6 billion | 6% |

| 2019/20 | $12.5 billion | 5% | $8.1 billion | 6% |

| 2020/21 | $12.8 billion | 2% | $8.4 billion | 5% |

| 2021/22 | $13.7 billion | 3% | $9 billion | 4% |

| 2022/23 | $15.8 billion | 10% | $10.5 billion | 13% |

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.28

In 2021/22, the total operating expenditure for all councils was $13.7 billion. This was a 3% increase on what was budgeted ($13.3 billion). In 2022/23, the total operating expenditure for all councils was $15.8 billion. This was a 10% increase on what was budgeted ($14.4 billion).

2.29

When Auckland Council is excluded from these results, councils incurred higher than expected total operating expenditure. In 2021/22, this was $9 billion (compared with a budget of $8.7 billion). In 2022/23, this was $10.5 billion (compared with a budget of $9.3 billion).

2.30

Figure 4 shows the main categories of councils' operating expenditure, as well as councils' actual operating expenditure.

Figure 4

Subcategories and actual operating expenditure, 2018/19 to 2022/23

| Year | Depreciation and amortisation | Employee costs | Finance costs | Other operating expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/19 | 22% | 23% | 7% | 48% |

| Actual $million | 2,524.2 | 2,643.3 | 848.4 | 5,635.2 |

| 2019/20 | 21% | 23% | 7% | 49% |

| Actual $million | 2,661.9 | 2,876.1 | 806.8 | 6,137.4 |

| 2020/21 | 22% | 23% | 6% | 49% |

| Actual $million | 2,863.2 | 2,907.3 | 725.1 | 6,323.8 |

| 2021/22 | 22% | 23% | 6% | 49% |

| Actual $million | 3,039.3 | 3,153.1 | 780.0 | 6,763.0 |

| 2022/23 | 22% | 22% | 7% | 49% |

| Actual $million | 3,539.3 | 3,393.1 | 1,074.0 | 7,808.4 |

Note: Other operating expenditure may include items such as repairs and maintenance, electricity, ACC levies, discretionary grants/contributions, rental and operating lease costs, "bad debts" written off, maintenance contracts, and impairment of property, plant, and equipment.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.31

In 2021/22, employee costs for all councils were 3% higher than budgeted. In 2022/23, employee costs for all councils were 8% higher than budgeted.

2.32

In 2021/22, regional and rural councils had the highest increases in employee costs (7% higher than budgeted). In 2022/23, employee costs for regional councils were 8% higher than budgeted, and employee costs for rural councils were 9% higher than budgeted. However, metropolitan councils had the highest increases in employee costs in 2022/23 (18% higher than budget).

2.33

In our 2021 insights report, we highlighted an overall increase of 2% in employee costs. We also said that we often heard about the challenges councils faced in recruiting and retaining skilled staff, particularly in the engineering and regulatory fields.

2.34

We still hear about these challenges in our regular engagement with councils. Although this has generally been more of an issue for smaller councils, skill gaps are becoming more prominent in metropolitan areas as well.

2.35

Other operating expenditure was 4% higher than budgeted in 2021/22 and 8% higher than budgeted in 2022/23. Actual other operating expenditure was $6.8 billion in 2021/22 and $7.8 billion in 2022/23.

2.36

There were several reasons for these increases – including the ongoing impact of inflationary cost pressures, higher insurance premiums, and increasing electricity costs. Another common reason was remediation works in response to severe weather events.

2.37

For example, in 2022/23, Central Hawke's Bay District Council's other operating expenditure was 101% higher than budgeted. This was partly attributed to costs to repair roads damaged by Cyclone Gabrielle.

2.38

Gisborne District Council's expenditure on operating activities was 114% higher than budgeted. The Council's annual report said that operating expenditure was impacted by a total of $67 million of emergency roading works. The Council spent $51 million to fix the damage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle and Cyclone Hale.

2.39

In our 2021 insights report, we noted that liabilities from leaky-home claims were a long-standing issue that continued to have significant expenditure implications for some councils.

2.40

In its 2022/23 annual report, Queenstown Lakes District Council included additional expenditure from leaky-home settlements, legal fees for weathertightness issues, and increased costs for interest, asbestos removal, electricity, insurance, and forestry. As a result, Queenstown Lakes District Council's other operating expenditure was 125% higher than budgeted.

2.41

In 2021/22, finance costs for all councils were 2% lower than budgeted. However, in 2022/23, finance costs were 20% higher than budgeted. Generally, finance costs include interest expenses and amounts paid or payable on borrowings and debt instruments.

2.42

Reasons for the largest decreases in finance costs for 2021/22 included:

- a decrease in the use of bank overdraft facilities (Environment Southland);

- reduced borrowing (Napier City Council);

- unbudgeted favourable non-cash valuation on derivative financial instruments (Palmerston North City Council); and

- not requiring external debt, resulting in minimal external interest incurred (Southland District Council).

2.43

In our 2021 insights report, we suggested that the 22% decrease in finance costs for 2020/21 indicated that councils were being more conservative. We concluded that councils were likely anticipating that cashflow challenges would continue after the Covid-19 pandemic.

2.44

By 2022/23, finance costs began to increase again. Higher interest costs were one reason for this, which also reflected increasing debt levels to fund more capital expenditure.

Councils' annual reports could better describe how they use central government funds

2.45

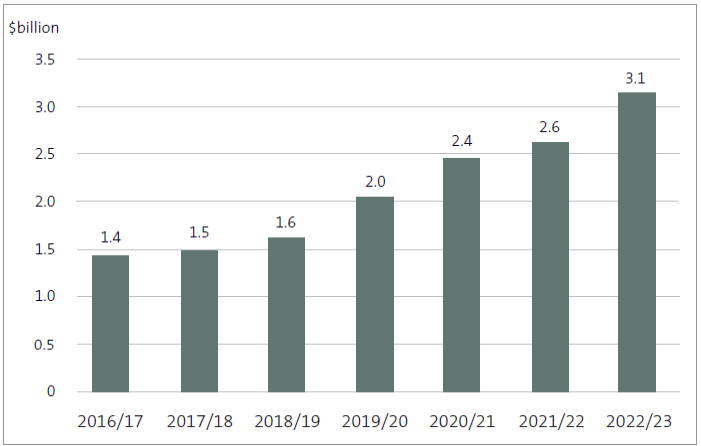

Figure 2 shows that a significant amount of councils' revenue comes from subsidies and grants. Subsidies and grants enable councils to provide many of their services to their communities. Subsidies and grants revenue has become increasingly important to councils, and it has almost doubled since 2018/19 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Subsidies and grants revenue recognised by councils, 2016/17 to 2022/23

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.46

Because councils are not required to consistently report a breakdown of the subsidies and grants they receive in their annual report, it is not clear what is causing this increase.

2.47

We expect that most grants and subsidies that councils receive are from central government. Waka Kotahi co-funds councils' public passenger transport and roading activities. Central government has made several other funds available that councils could apply for, including:

- "shovel ready" funding;

- the Strategic Tourism Assets Protection Programme funding;

- Jobs for Nature; and

- Provincial Growth Funding and the "better off" funding that was made available through the previous government's Three Waters Reform Programme.

2.48

Central government will also financially support councils during emergencies, such as Cyclone Gabrielle.

2.49

When we look at councils' annual reports, it is not always clear what councils have achieved with central government funding. Councils' reporting of what they have achieved with regular and ongoing funding sources (such as from Waka Kotahi) is generally good.

2.50

We have previously stated that councils report information about what they did with other funding sources in a fragmented way.6 This was still an issue in the 2022/23 annual reports we looked at.

2.51

In our view, councils need to be more transparent in their annual reports about what central government funding they have received and what they used it for. We consider that this is important context for when councils report on what they have achieved. We plan to examine this matter in the future.

Processing times for building consent applications

2.52

Councils have a statutory requirement to process most building consent applications in 20 working days (because regional councils do not process building consent applications except for dams, this applies to 67 out of the 78 councils). Our auditors regularly look at how councils meet this requirement as part of their audit of councils' non-financial performance information.

2.53

The requirement to process most building consent applications in 20 working days can also be used as an indicator of councils' effectiveness in responding to growth and development.

2.54

During the past few years, we reported that most councils did not meet the statutory time frames for processing building consent applications. This trend worsened in 2021/22 and slightly improved in 2022/23.

2.55

Although this remains a concern, the total number of building consent applications processed during 2021/22 and 2022/23 increased significantly from previous years. The workload of council staff would have also increased.

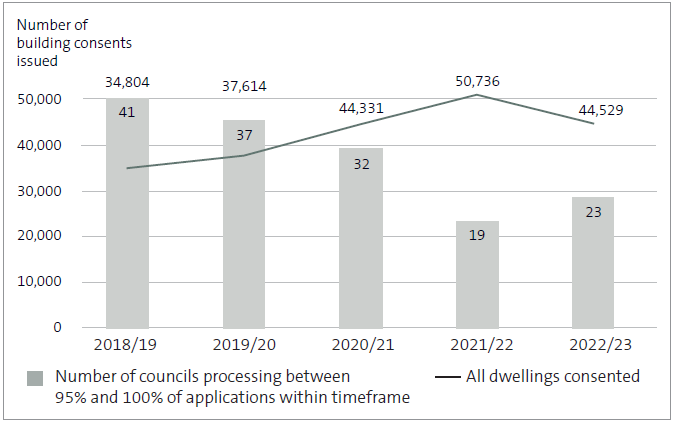

2.56

After the significant 18% increase in building consent applications processed in 2020/21 (a total of 44,331 applications processed), building consent applications increased to more than 50,700 in 2021/22 (a 14% increase). This is the highest number of building consent applications processed in a single year ever recorded.

2.57

In 2022/23, the number of building consent applications processed decreased to about 44,500 (a 12% decrease from 2021/22). This reflects the general slowdown in the housing market after significant activity in 2021 and 2022. However, the number of applications is still high compared to previous years. Figure 6 shows the number of building consent applications processed from 2018/19 to 2022/23.

Figure 6

Total number of building consent applications issued for new dwellings and council performance, 2018/19 to 2022/23

Source: Statistics New Zealand.

2.58

The large increase in higher-density housing throughout the country is one of the main reasons building consent applications have increased in the past few years. Between 2020/21 and 2021/22,7 applications for new multi-unit dwellings increased by 35% to more than 26,800.8 However, between 2021/22 and 2022/23,9 applications decreased by 3% to little more than 26,000.

2.59

A large number of building consent applications are in the Auckland region. Auckland Council issued a record 21,609 building consents for new dwellings in 2021/22 (a 13.5% increase from 2020/21).

2.60

The number of building consent applications Auckland Council processed represented 40% of the total increase in building consents issued and 50% of the total increase in multi-unit building consents issued between 2020/21 and 2021/22.10

2.61

This trend did not continue in 2022/23, and the total number of building consent applications processed in Auckland decreased to 19,085 (a 11.7% decrease from 2021/22).11 However, this is the second-highest number of building consent applications processed annually in Auckland. Multi-unit dwellings made up 77% of this total, which shows the significant shift towards high-density development in the region.

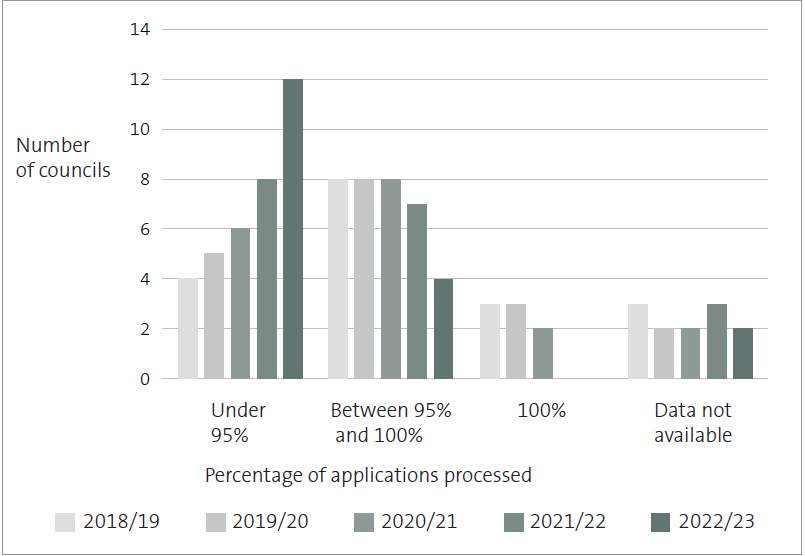

2.62

In 2021/22, 59 councils reported on their performance in processing building consent applications.12 Of those, only two reported that they had processed 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame of 20 working days (compared with six councils in 2020/21).13

2.63

An additional 17 councils reported that they had processed between 95% and 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame (compared with 26 councils in 2020/21). Figure 6 shows this as a total for all councils since 2018/19.

2.64

In 2022/23, 58 councils reported on their performance in processing building consent applications. Of those, only three reported that they had processed 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame,14 and 20 councils reported they had processed between 95% and 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame.

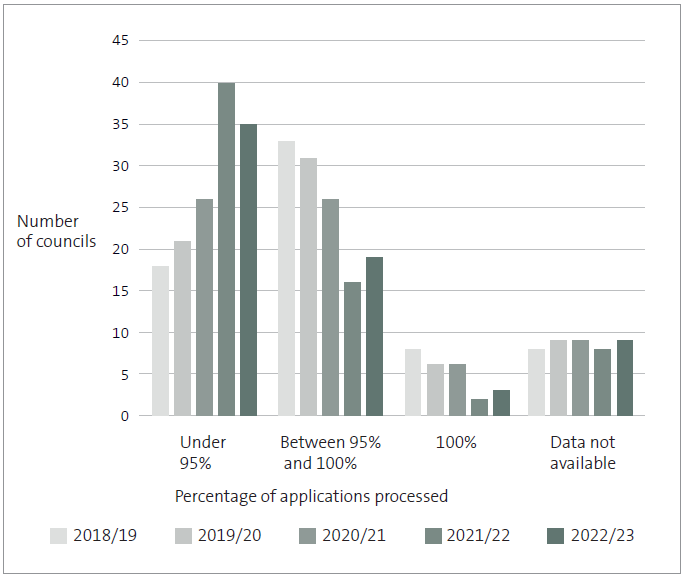

2.65

Overall, the number of councils not meeting the statutory time frame for processing building consent applications is large and increasing. In 2022/23, 35 councils reported processing fewer than 95% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame (compared with 26 councils in 2020/21 and 40 councils in 2021/22).

2.66

This is a matter that councils need to address. Although they improved slightly in 2022/23, councils need to process building consent applications more efficiently so that they can meet challenges such as the higher number and complexity of building consent applications (including those for multi-unit dwellings).

2.67

We did not find usable performance information about the timeliness of building consent applications for eight councils in 2021/22.15 This increased to nine councils in 2022/23.16 These councils did not have a performance measure or used alternative measures.

2.68

We expect all councils to report their performance against the statutory time frame, especially Tier 1 councils under the National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2020 (see the Appendix). Because issuing and monitoring building consents is a core council function, we expect councils to report this information.

2.69

Figure 7 shows the overall results in the timeliness of building consent applications processed since 2018/19.

Figure 7

Percentage of building consent applications processed within 20 working days, 2018/19 to 2022/23

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports. Three reports for 2022/23 had not been finalised when we did our analysis.

Processing times for resource consent applications

2.70

Under the Resource Management Act 1991, all councils have a statutory requirement to process resource consent applications within set time frames. Time frames depend on the type of consent.17

2.71

This requirement can be used as an indicator of councils' effectiveness in responding to growth and the timeliness of their service delivery. Regional councils process resource consents and coastal, discharge, and water permits.

2.72

In 2021/22, 71 of 78 councils included performance information about processing resource consent applications in their annual reports. We did not find usable performance information in the other seven councils' annual reports.

2.73

In 2022/23, we found usable performance information about processing resource consent applications for 70 of 78 councils. Three of these councils had not adopted their annual reports when we did our analysis. Because issuing and monitoring resource consent applications is a core council function, we expect councils to report this information.

2.74

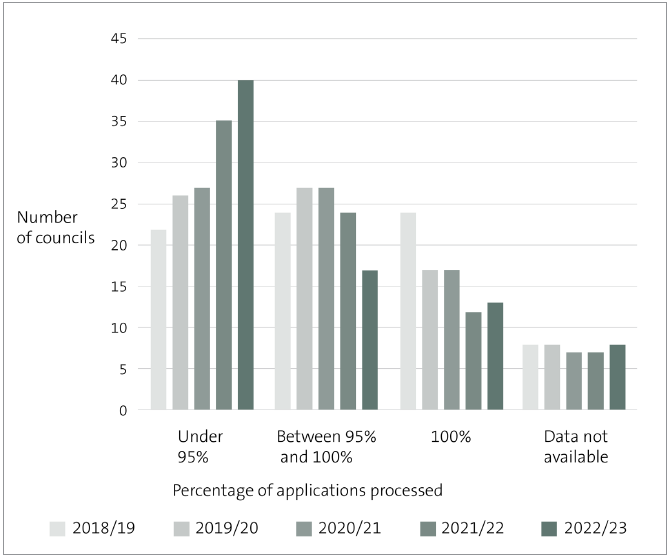

Figure 8 shows trends in timeliness for all councils' performance in processing resource consent applications from 2018/19 to 2022/23. Performance in 2021/22 and 2022/23 declined compared with 2020/21. This is apparent from the increasing number of councils that processed fewer than 95% of resource consent applications (27 councils in 2020/21, 35 councils in 2021/22, and 40 councils in 2022/23).

Figure 8

Councils' compliance with statutory time frames for processing resource consent applications, 2018/19 to 2022/23

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.75

Councils consistently identified high work volumes, planning staff and consultant capacity, the increasing complexity of applications, and the impact of Cyclone Gabrielle as reasons for not achieving performance targets.

2.76

In 2021/22 and 2022/23, none of the 18 Tier 1 councils processed 100% of resource consent applications within the statutory time frame. These councils also reported a steep decline in this area. Twelve of the 18 Tier 1 councils processed fewer than 95% of resource consent applications within the statutory time frame (an increase from eight councils in 2021/22).

2.77

Auckland Council's performance affected the overall result. Auckland Council processed almost 16,000 resource consent applications in 2021/22, which was about a third of all consents for the year. In the last three years, Auckland Council's performance in processing resource consent applications within the statutory time frame declined from 77.6% in 2020/21 to 71.2% in 2021/22 and 65.7% in 2022/23.

2.78

Figure 9 shows trends in timeliness for Tier 1 councils defined by the National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2020.

Figure 9

Tier 1 councils' compliance with statutory time frames for processing resource consent applications, 2018/19 to 2022/23

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.79

No complete dataset is available that shows the number of resource consent applications processed by councils in 2022/23. However, the Ministry for the Environment has data for 2021/22.18

2.80

In 2021/22, councils processed 39,773 resource consent applications (compared with 37,101 in 2020/21). This was the highest number of resource consent applications processed since 2016/17. When reporting their performance, many councils referenced their high workloads in 2021/22 and 2022/23.

2.81

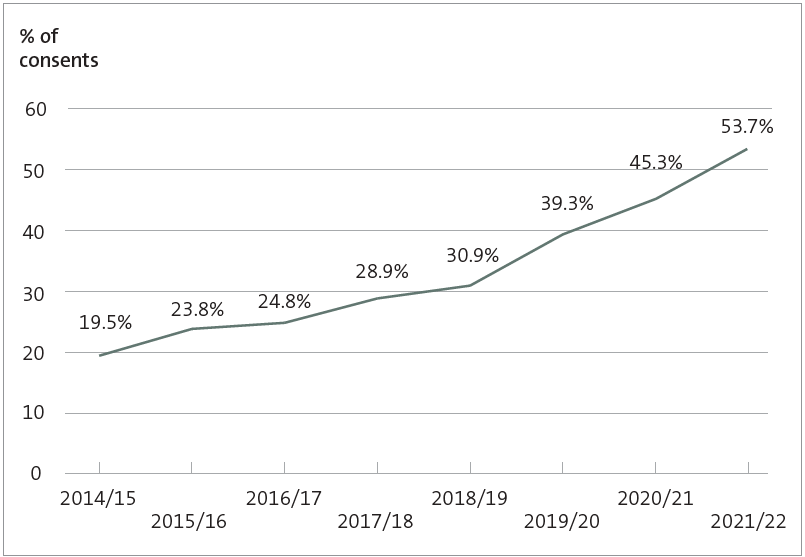

The Ministry for the Environment also identified an ongoing trend of councils increasing their use of section 37 of the Resource Management Act to extend the time limits for processing resource consent applications (see Figure 10). In 2020/21, councils used section 37 of the Resource Management Act for 45.3% of resource consent applications. In 2021/22, this increased to 53.7%. We do not yet know the percentage for 2022/23.

Figure 10

Percentage of resource consent applications that used at least one section 37 (extended time frames) in their processing, 2014/15 to 2021/22

Source: Ministry for the Environment (2023), "Patterns in Resource Management Act implementation: National Monitoring System data from 2014/15 to 2021/22", page 16, at environment.govt.nz.

2.82

Most councils report on performance measures for processing resource consent applications within statutory time frames. However, performance measures relating to timeliness varied between councils, and not all councils explained why they missed their targets. It is good practice for councils to explain why they missed targets in their annual reports. We encourage them to do this.

2.83

Local councils do not adopt performance measures for monitoring, compliance, and environmental outcomes as commonly as regional councils. Because of this, the performance information of local councils, including the effects of consenting decisions, is less transparent. This also affects the ability to compare councils.

2.84

We continue to encourage councils to actively review the effectiveness of their resource consent performance measures, to critically evaluate their performance, and to seek to improve their processing times.

Three waters performance measures

2.85

In this section, we consider whether increased investment in water assets translates into improved performance over time and describe how councils reported on their performance measures for three waters.19

2.86

In 2022/23, councils as a whole invested more than $2.5 billion in three waters assets. This is 56% of total council spending on infrastructure assets for the year and an increase of $207.7 million (9%) from 2021/22. Although this is smaller than other year-on-year increases since 2018/19, it reflects the recent trend of councils' increasing focus and reinvestment in three waters assets.

2.87

Although councils' total spending on three waters assets has steadily increased since 2012/13, councils are still not adequately reinvesting in their assets. As we highlight in Part 4, renewal-related capital expenditure for councils is less than 100%. This indicates that assets are not being replaced at the same rate as they are being run down. If councils underinvest in their assets, there is a bigger risk of asset failure and a resulting reduction in service levels.

2.88

In the past, we found that renewals spending as a proportion of the depreciation expense was lower for three waters infrastructure than for other infrastructure. In Part 4, we discuss how this trend changed slightly in 2021/22 and 2022/23 (see paragraphs 4.32-4.36). Water supply and wastewater had a higher renewals rate than other infrastructure categories. However, stormwater renewals remain lower than every other infrastructure category.

2.89

Although councils have had a particular focus on three waters in recent years, they are also grappling with affordability issues. In some instances, these issues have constrained the amount of funding available for water asset renewals.

Does increased investment in three waters lead to improved performance?

2.90

Councils are required to report their performance against specific performance measures for three waters.20 The Department of Internal Affairs' website provides an outline of these measures.21 Councils report these performance measures' targets as either "achieved" or "not achieved" in their annual reports. We combined the responses from all councils to see what percentage of targets councils reported as "achieved".

2.91

This helps form a picture of which performance measure targets councils are generally achieving and which they are not throughout the country. In some instances, councils did not report whether they achieved a particular target.

2.92

Importantly, this analysis does not take account of the size of the population in each council boundary. Therefore, the results should not be considered as reflecting council performance for the population of New Zealand as a whole.

2.93

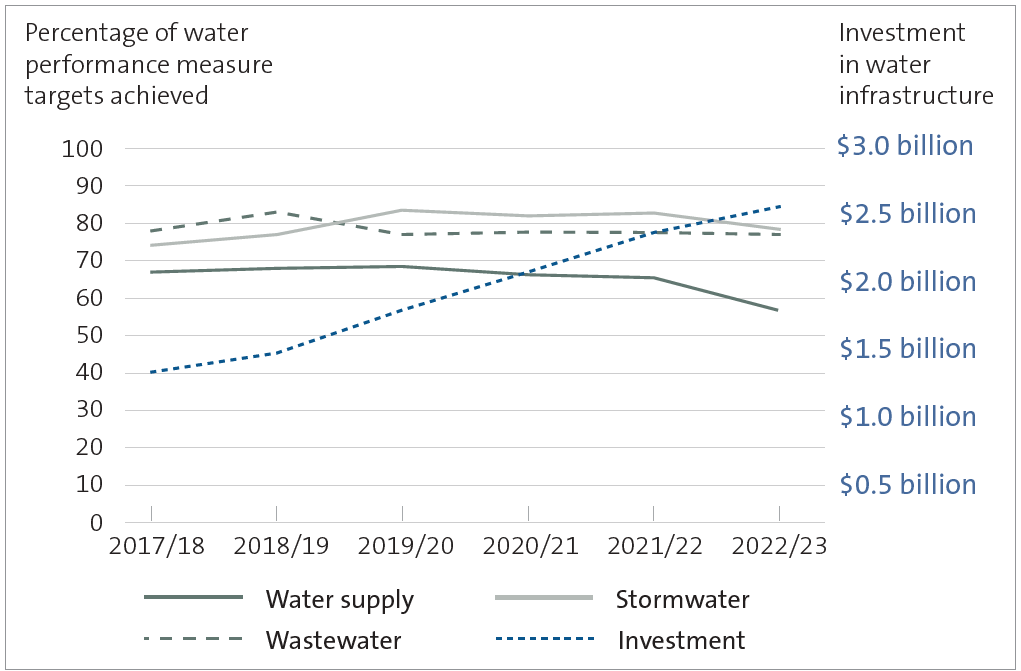

At an aggregate level, performance against the wastewater and stormwater measures has been relatively consistent during the past six years. However, performance against the water supply measures has decreased since 2019/20 (see Figure 11). In contrast, councils' annual investment in water infrastructure has increased significantly during the last six years, having doubled since 2017/18.

Figure 11

Percentage of water supply, wastewater, and stormwater performance measure targets achieved, compared to the level of investment in three waters assets, 2017/18 to 2022/23

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.94

Despite the increased investment in three waters assets, there has not been an improvement in reported performance. In fact, there has been a significant deterioration in achievement of water supply performance measure targets.22

2.95

Although we expect a time lag between increased investment and an improvement in performance, the increased annual investment in three waters has been consistent during the last six years, with little or no sign of improved performance.

2.96

Overall, the results for 2021/22 and 2022/23 show that councils' achievement of water supply measure targets is their lowest area of performance. Councils achieved fewer than 60% of water supply performance measure targets in 2022/23. Councils that report "not achieved" against the mandatory drinking water performance measure targets should prioritise actions to improve performance.

2.97

The historical underinvestment in three waters infrastructure might have contributed to overall performance. Councils have an opportunity to address this in their 2024-34 long-term plans by planning to spend more on their water assets. However, we recognise that uncertainty about the water reforms, as well as councils' affordability issues, make this challenging.

2.98

We provide further detail on council performance for each of the three waters. In some instances, we consider councils under five different subsectors (see the Appendix).

Councils' performance against water supply measures

2.99

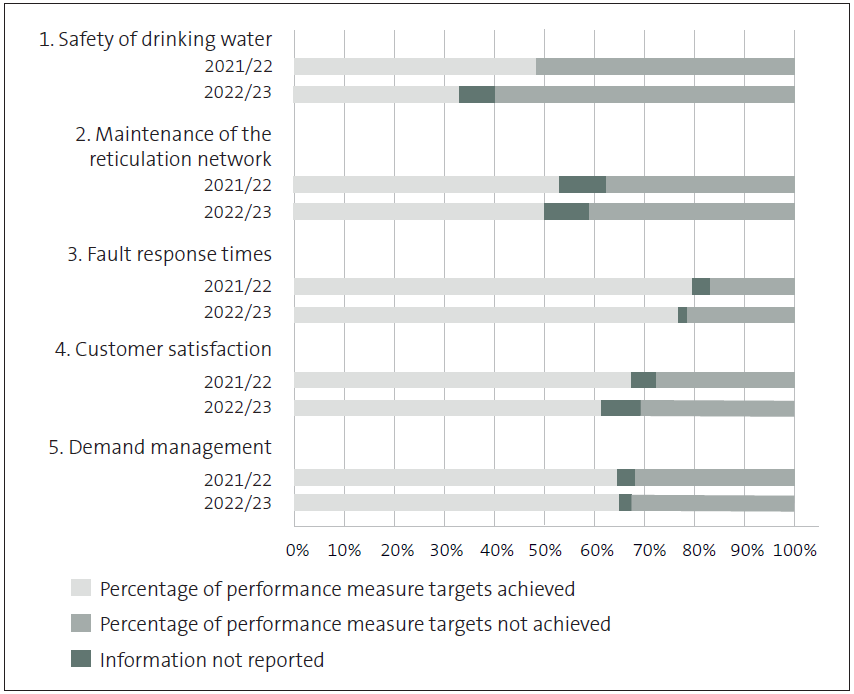

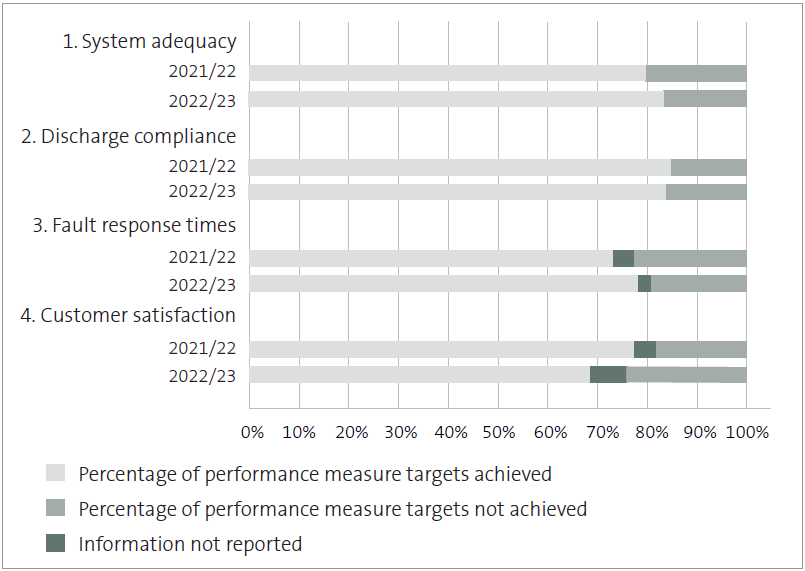

Overall, 56.9% of water supply performance measure targets in 2022/23 could be considered "achieved", which is a decrease from the previous two years (66.3% in 2020/21 and 65.5% in 2021/22). Figure 12 shows each measure in this category for 2021/22 and 2022/23.

Figure 12

Percentage of water supply performance measure targets achieved in 2021/22 and 2022/23

Note: "Information not reported" means councils have not measured that aspect of their performance.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.100

The lowest performance in both 2021/22 and 2022/23 was for "safety of drinking water" measures. Councils achieved 48.3% of safe drinking water performance measure targets in 2021/22, but achieved only 33% of these targets in 2022/23.

2.101

This is an area of significant concern. Our article "Testing the water: How councils report on drinking water quality" provides further analysis on the issues behind this low rate of performance.23

Councils' performance against wastewater measures

2.102

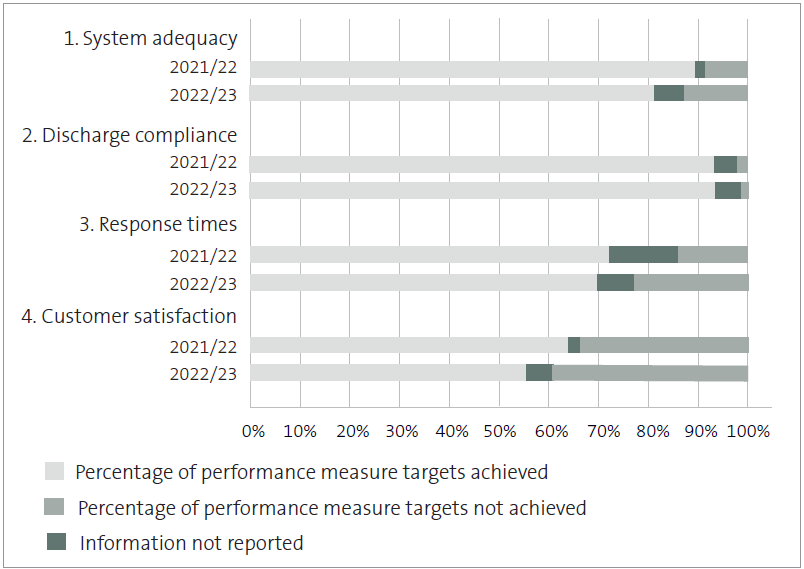

Overall, 77.1% of wastewater performance measure targets were considered "achieved" in 2022/23, which was largely consistent with the last two years (77.8% in 2020/21 and 78.2% in 2021/22). Figure 13 shows each measure in this category in the previous two financial years.

Figure 13

Percentage of wastewater performance measure targets achieved in 2021/22 and 2022/23 for all councils

Note: "Information not reported" means councils have not measured that aspect of their performance.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.103

Councils did not perform as well against the "fault response times" measure in 2021/22 (73% of fault response time performance measure targets were achieved) and the "customer satisfaction" measure in 2022/23 (68.4% of customer satisfaction performance measure targets were achieved).

2.104

The performance against the "fault response times" measure in 2021/22 appears to be mainly affected by poor performance by rural councils. As a group, rural councils achieved only 61.1% of these performance measure targets.

2.105

It appears that the performance against the "customer satisfaction" measure in 2022/23 is mainly affected by poor performance by metropolitan councils (excluding Auckland Council) and rural councils. As a group, metropolitan councils achieved only 65.2% of these performance measure targets and rural councils achieved only 62.1%.

Councils' performance against stormwater measures

2.106

Overall, 78.6% of councils' stormwater performance measure targets were considered "achieved" in 2022/23. This is a decrease from 2021/22, where 82.8% of stormwater targets were considered "achieved". Figure 14 shows each measure in this category for 2021/22 and 2022/23.

Figure 14

Percentage of stormwater performance measure targets achieved in 2021/22 and 2022/23 for all councils

Note: "Information not reported" means councils have not measured that aspect of their performance.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

2.107

"Customer satisfaction" was the poorest performing measure in the category in 2021/22 (64% of customer satisfaction performance measure targets were achieved) and in 2022/23 (55.7% of targets were achieved). These results were mainly due to poor performance by rural councils (rural councils achieved only 40% of these targets in 2022/23).

3: Our analysis for 2022/23 excludes Buller District Council, Rotorua District Council, and West Coast Regional Council. This is because the audited annual reports for these councils were not available when we carried out our analysis. These councils remain in the previous year results because we considered that they are too small to impact our analysis.

4: The three waters are drinking water supply, wastewater, and stormwater.

5: A found asset is an asset that an organisation owns but did not initially record as such.

6: For example, see Controller and Auditor-General (2022), Insights into local government: 2021, at oag.parliament.nz.

7: Statistics New Zealand (2022), "Building consents issued: June 2022", at stats.govt.nz.

8: Multi-unit dwellings include apartments, retirement village units, townhouses, flats, and units.

9: Statistics New Zealand (2023), "Building consents issued: June 2023", at stats.govt.nz.

10: Statistics New Zealand (2022), "Building consents issued: June 2022", at stats.govt.nz.

11: Statistics New Zealand (2023), "Building consents issued: June 2023", at stats.govt.nz.

12: Councils that did not have data available to report in 2021/22 included Central Hawke's Bay District Council, Chatham Islands Council, Clutha District Council, Gore District Council, Hamilton City Council, Timaru District Council, and Whakatāne District Council. In addition, Kawerau District Council collects data but does not publish it in its annual report.

13: These councils were Mackenzie District Council and Waitaki District Council.

14: These councils were Mackenzie District Council, Waitaki District Council, and Far North District Council.

15: These councils include Central Hawke's Bay District Council, Chatham Islands Council, Clutha District Council, Gore District Council, Hamilton City Council, Kawerau District Council, Timaru District Council, and Whakatāne District Council.

16: These councils include Chatham Islands Council, Clutha District Council, Gore District Council, Hamilton City Council, Kawerau District Council, Timaru District Council, and Whakatāne District Council. Buller District Council and Rotorua District Council were not included because the audited annual reports for these councils had not been finalised when we did our analysis.

17: The time frames are 10 working days for fast-track consents, 20 working days for non-notified consents, within 20 working days after close of submissions for notified consents where no hearing is required, and within 15 working days after the hearing for notified consents where a hearing is required.

18: Ministry for the Environment (2023), "Patterns in Resource Management Act implementation: National Monitoring System data from 2014/15 to 2021/22", at environment.govt.nz.

19: Our analysis of three waters performance measures includes the 67 territorial authorities and Greater Wellington Regional Council. Buller District Council and Rotorua District Council were not included in our 2022/23 analysis because the audited annual reports for these councils had not been finalised when we did our analysis. The other 10 regional councils are not responsible for water assets and services, so they do not report these performance measures.

20: These requirements are set out in the Non-Financial Performance Measures Rules 2013 provided by the Secretary for Local Government.

21: See the "Local Government Policy" section on the Department of Internal Affairs website, at dia.govt.nz.

22: Our comparison of investment against performance measures is an indicator only. Although increased investment might allow for improvements in performance, there is not a direct causal relationship. There might also be a time lag between increased investment and an improvement in performance.

23: See Controller and Auditor-General (2024), "Testing the water: How councils report on drinking water quality", at oag.parliament.nz.