Part 6: Climate change

6.1

In this Part, we discuss how the need for climate action is becoming more urgent. We also discuss the climate change matters disclosed in the 2021-31 long-term plans. This includes:

- our expectations for the 2021-31 long-term plans and our approach to reviewing the references to climate change in the plans;

- how councils are factoring climate change risks and vulnerabilities into their long-term planning;

- the types of climate actions councils are taking, including the councils that declared climate emergencies; and

- the further work we propose to do to consider climate action by councils.

The need for climate action is becoming more urgent

6.2

The need to take urgent action to respond to climate change and its impacts is gaining momentum under the Government's climate response framework.30 This reflects the international consensus that urgent action is needed in the next decade to manage global temperature rise.

6.3

Adapting to, and mitigating the effects of, climate change presents significant challenges for councils. Given the role councils have in environmental planning and regulation, transport planning, and responding to natural hazards and extreme weather events, much of the responsibility for dealing with, and adapting to, climate change effects falls to them.

6.4

There is also an increased focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and on climate-related reporting. In order to meet New Zealand's legislated target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, significant transformation and change will be needed throughout all sectors of the economy.

6.5

The Government's Emissions Reduction Plan, released in May 2022, sets out the actions needed to meet national emissions reduction targets and the principles that underpin the Government's approach.31 The Emissions Reduction Plan and several of the principles could provide useful guidance for councils in their climate action planning.

Our previous work

6.6

After auditing the 2018-28 long-term plans, we observed that:

- most councils were deferring making decisions about how to respond to the effects of climate change because there was too much uncertainty;

- many councils assumed that climate change would not significantly affect their communities in the period of the long-term plan and that there would be no major natural hazard events in that period;

- councils had a limited understanding of the risks natural hazards pose and how climate change could affect their infrastructure assets; and

- it made little sense for all councils to individually consider how to improve their reporting on climate change issues, and there was a need for increased leadership from both central and local government on climate reporting and data requirements.32

6.7

We also reviewed the climate-related content of councils' 2018/19 annual reports. We observed that many councils were giving greater attention to climate change in their governance and decision-making, including some collaborative arrangements in four council regions.

6.8

A small number of councils had formed climate action committees, and some had allocated staff or funding to climate change work and projects. We observed that audit and risk committees play an important role in assisting councillors to consider climate-related risks to achieving objectives – in particular, a council's ability to deliver services to the community.33

Our expectations for the 2021-31 long-term plans

6.9

We expected that climate change would be more prominent in the 2021-31 long-term plans than in previous plans. In our previous work, we had suggested that councils should have a comprehensive discussion of resilience and climate change issues with their communities as part of their 2021-31 long-term plans.34

6.10

As a result, climate change assumptions and disclosures were a focus for our auditors when auditing the 2021-31 long-term plans.

6.11

We expected that all councils would include an assumption about climate change effects and impacts in their long-term plan, with some supporting evidence. The expected effects of climate change could include increases in sea level, rainfall events, floods, droughts, and the severity of adverse weather events and temperature changes.

6.12

We also expected councils to show how much they understand the potential impacts that the expected effects of climate change will have on their critical assets and communities.

6.13

For most councils, these are likely to include impacts on:

- three waters services – this includes water supply security issues, reduction in water quality, increased wastewater overflows from heavy rainfall, and flood protection assets not working;

- the transportation network – disruption from sea-level rise or flooding and landslides, leading to increased maintenance costs;

- coastal infrastructure and property – sea-level rise causing coastal erosion that will put property and assets at risk, and may mean some places become uninsurable; and

- biodiversity and pest management – changes in the type and distribution of pest species.

6.14

In assessing whether a climate-related assumption is reasonable, our auditors look at the council's process for making the assumption (including supporting information such as an assessment of climate effects from an expert climate organisation) and how the council has considered the impacts of that information on its activities and its community.

6.15

There may be instances where a community is already experiencing significant climate change effects. In these instances, more detailed modelling of climate change effects may be needed to demonstrate the reasonableness and supportability of the assumption.

Assessing climate-related actions and their priority

6.16

As well as considering climate change assumptions, which are largely focused on how councils are planning to adapt to the effects of climate change, we wanted to assess the steps that councils are taking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and whether councils are prioritising climate action over other priorities.

6.17

To carry out our assessment, we:

- reviewed our auditors' findings on the climate-related disclosures in the long-term plans;

- compared the number of references to climate change in the 2021-31 long-term plans to the number in the 2018-28 long-term plans;

- reviewed whether the long-term plans refer to climate change as a strategic issue for the council – for example, in the mayor/chairperson's or chief executive's introduction or in the description of significant challenges and issues; and

- reviewed the climate actions councils are taking, including those that declared climate emergencies.

How councils are factoring climate change risks and vulnerabilities into their long-term planning

Climate change assumptions

6.18

We are pleased to note that:

- all councils included a disclosure about climate change effects in their long-term plan;

- our auditors did not raise any significant concerns about the climate change assumptions in the 2021-31 long-term plans (but suggested improvements in some instances);

- our auditors did not draw attention to any climate-related matters or concerns in their audit reports.

6.19

Councils take a fairly standard approach to setting out their climate change assumptions. The climate change assumption often involves a description of the likelihood and impact of climate change, with supporting information about forecast district- or region-specific climate effects. It then sets out possible impacts on council infrastructure, activities, or communities.

6.20

To show how a council's approach has evolved, we provide an example of a climate change assumption from Central Otago District Council's 2021-31 long-term plan (see Figure 19) and compare it with the climate change assumption in its 2015-25 long-term plan (see Figure 20).

Figure 19

Central Otago District Council's long-term plan 2021-31 climate change assumption

| Climate Change |

|---|

| Central Otago District Council commissioned Bodeker Scientific to undertake analysis and prepare a report of climate change impacts on the Central Otago District in 2017. This includes the projection under the worst case or highest warming scenario, as well as the implications this may have for the district. The Otago Regional Council has engaged Tonkin and Taylor to undertake analysis of the expected impacts of climate change on the wider Otago Region. The implications of climate change on Central Otago presented in the Tonkin and Taylor report are similar to those in the Bodeker Scientific report. Central Otago District is predicted to warm by several degrees by the end of the century. Total precipitation is not projected to change much in the district. However, the distribution and intensity of rainfall is likely to alter, with a greater likelihood of more frequent extreme rainfall events. These events have occurred infrequently in the past, which provides valuable information regarding the consequences of these events to improve planning for the future. Central Otago District Council declared a climate crisis in Central Otago on 25 September 2019. Further details of this can be found in the Infrastructure Strategy. Council has joined the Toitū Carbon Reduce certification scheme, which measures, manages and reduces its greenhouse gas emissions. This is a key strategic focus of Council's Sustainability Strategy. The emission sources that Council is responsible for have been measured for the 2017-18, 2018-19, and 2019-20 financial years. Emissions are broken down into three categories by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, and by Council activity in order to better understand the source. These will be audited by June 2021, along with Council's emissions management and reduction plan. There is a risk that if these assumptions are wrong, then Council could face growing costs from more frequent weather events, damage to assets and growing insurance costs. Council continues to monitor the impact of climate change across Council's assets. The risk of direct impact from climate change within the 10-Year Plan timeframe is medium. |

6.21

In contrast, the climate assumption information in the 2015-25 long-term plan and infrastructure strategy focused on uncertainty.

Figure 20

Central Otago District Council's long-term plan 2015-25 climate change assumption

| Climate Change Resilience |

|---|

| At present the impacts climate change may have on Central Otago are largely unknown. A wetter climate is a likely scenario and will impact on the district's stormwater and roading assets. The most common natural hazards that affect the transportation network are flooding and snow. Council has established procedures for responding to these events. The degree and severity of these scenarios is not yet known. Subsequently, no significant individual capital projects relating to climate change are identified in this strategy. The impact of these events on the transportation network will be monitored from 2014 using the One Network performance framework for resilience. |

6.22

Central Otago District Council's approach has evolved significantly since its 2015-25 long-term plan. Its current approach is supported by expert analysis of climate effects for the district and Otago region, and a decision to declare a climate crisis and take actions in response.

6.23

Our auditor reviewed the Council's climate-related actions and assumption. Our auditor concluded that it was reasonable and supportable and acknowledged an appropriate level of uncertainty. Our auditor observed that the Council has been taking steps in the right direction to identify and mitigate climate change. This was clearly set out in the long-term plan.

The prominence of climate change disclosures in the 2021-31 long-term plans

6.24

We checked whether climate change is more prominent in the 2021-31 long-term plans than in the 2018-28 long-term plans. We did so by:

- counting references to "climate change" in the 2018-28 long-term plans and the 2021-31 long-term plans; and

- checking whether councils assessed climate change or climate action as a strategic priority issue up front in their 2021-31 long-term plans, compared to their 2018-28 long-term plans.

6.25

We acknowledge the limitations of this approach in assessing the prominence of climate-related content. Although it does not consider the quality of the information, it does give an indication of the relative emphasis councils gave to climate change in their 2021-31 long-term plans compared to their 2018-28 long-term plans.

6.26

In the 2018-28 long-term plans, we counted 2127 references to climate change. In the 2021-31 long-term plans, we counted 5161 references to climate change. This is an increase of 143%.

6.27

The average number of references to climate change in the 2018-28 long-term plans was 27. In the 2021-31 long-term plans, the average number was 66.

6.28

The highest number of references to climate change in a long-term plan was 355 and the lowest was 11. The largest change between the two long-term plans was Waitomo District Council. In its 2018-2028 long-term plan, climate change was referenced once. In its 2021-31 long-term plan, climate change was referenced 35 times.

6.29

About 55 councils (70%) identified climate change or climate action as a strategic priority at the front of their 2021-31 long-term plan, either in the mayor/chairperson's or chief executive's introduction or in a section on key issues or priorities. This was a notable increase from about 20 councils (25%) that mentioned climate change at the front of the 2018-28 long-term plans.

6.30

Many councils also identified climate change as a key challenge in their infrastructure strategies in both their 2018-28 and 2021-31 long-term plans. We also observed that some councils increasingly refer to climate action as well as climate change.

Taking climate action

6.31

We considered what councils said about their climate change activities in their 2021-31 long-term plans and what climate action they are taking or planning. We wanted to consider the nature and extent of climate action by councils and whether climate action is an urgent priority compared to councils' other priorities.

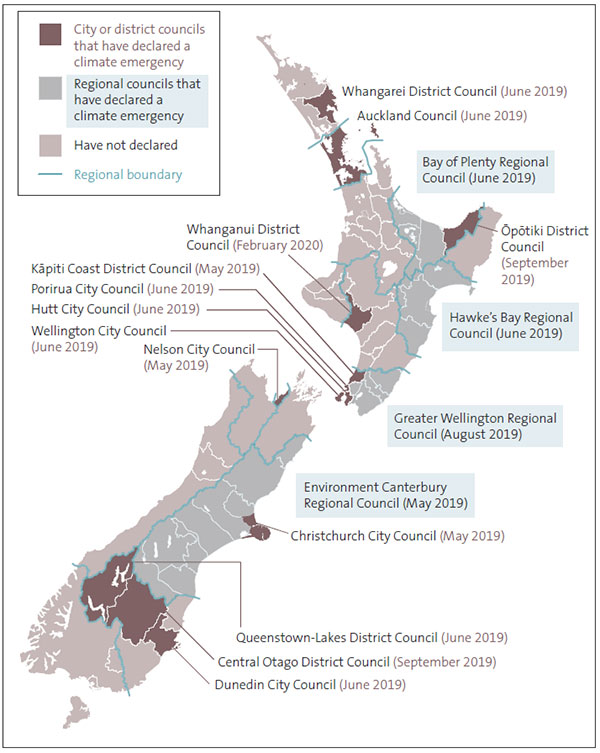

6.32

We paid particular attention to the 17 councils that had declared climate emergencies in 2019 and 202035 (see Figure 21). (Central Otago District Council has declared a climate crisis rather than a climate emergency.) We expected that declaring an emergency would result in tangible actions or programmes relating to mitigating and/or adapting to the effects of climate change and that these would be priority areas of council activity and investment evident in the long-term plan. This was the case for most of those councils.

6.33

We are aware that some councils have identified climate action as a strategic priority for the council and their communities but have not declared a climate emergency. We expect that our further planned work on climate action in local government will consider a broader range of councils than the councils that have declared a climate emergency.

Increasing resilience to climate change

6.34

We observed two main approaches to disclosing information about resilience to climate change. Councils either:

- have disclosed climate change resilience as a key challenge or issue in their long-term plans and have some work under way to consider what they are going to do about it (mainly focusing on adapting to climate change rather than reducing emissions); or

- say that they still have significant work to do to improve their understanding of their exposure and vulnerability to climate change and know that they need to do much more work to identify and consider the impact on the community and the council's assets and activities. This includes large councils such as Christchurch City Council and smaller councils such as the Chatham Islands Council.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

6.35

Several councils have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These are either the council's own emissions or the emissions for the city, district, or region, or both. In some instances, councils have ambitious targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

6.36

In a 2011 report, we assessed that about 25% of councils were taking steps to measure and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.36 They had begun doing so as part of former initiatives such as the Communities for Climate Protection New Zealand programme.

6.37

The 2021-31 long-term plans show that, for some councils, reducing emissions is their first step to taking action on climate change. This is illustrated by some of their statements in their plans.

Figure 21

The location of councils that have declared a climate emergency

6.38

For example, Waitaki District Council said that:

… [the] Council recognises the importance of reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. In 2019 we commissioned a greenhouse gas inventory report to provide some base data to help understand our organisation's emissions. This will be used to track and compare emissions over time.37

6.39

The Chatham Islands Council said that:

… [the] Council is committed to taking a collaborative approach to addressing any identified local causes and impacts of climate change, which includes strategically varying our core Council infrastructure and internal policies to reduce or mitigate any greenhouse gas emissions.38

6.40

Approaches to reducing their own corporate emissions include setting targets, providing data on a baseline year for emissions so they can assess progress, and having specific actions to reduce emissions.

6.41

Some councils have adopted New Zealand's legislated target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050 for their district or region.39 Some councils have interim targets, such as a 50% decrease by 2030. For example:

- Dunedin City Council aspires for Dunedin to be a carbon neutral city by 2030.

- Nelson City Council is adopting central government's targets and budgets for reducing emissions and aims to reduce its own greenhouse gas emissions for each council activity by 5% by 2025.

- Greater Wellington Regional Council aspires to be carbon neutral by 2030. It goes further by aspiring to be "climate positive" by 2035 through stock reduction, tree planting, and clean transport solutions.

Climate-related performance measures

6.42

Councils that have adopted emissions reduction targets need to have measures to assess their progress and be accountable to their communities. Some councils are beginning to include climate-related performance measures in their long-term plans, such as emissions reduction targets for their own operations or for their district or region, which they will report on in their annual reports.

6.43

Some measures are in the council's community outcome measures, rather than as part of their (audited) activity-related performance information. Some examples of measures include:

- measures of the council's greenhouse gas emissions from its own activities and facilities (corporate emissions), expressed in tonnes of CO2 emitted as a percentage change against a baseline, and including direct and indirect emissions;

- time-based measures for reduction in emissions from council-owned fuel vehicles – for example, 20% reduction in 2021/22, zero emissions by 2030;

- year-on-year reduction measures from a baseline starting year – for example, 10% decrease in emissions from baseline in organisational emissions year on year;

- measures that also include greenhouse gas emissions for all council subsidiaries, business units (and the share of jointly owned council-controlled organisations based on ownership share); and

- district-, city-, or region-wide measures, including:

- percentage reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from public transport services and assets;

- total city greenhouse gas emissions – for example, 43% reduction by 2030; and

- number of native trees planted in region.

6.44

This is a developing area, but it will become increasingly important for councils that wish to be accountable to their communities for their progress with climate action. We will consider the state of climate-related performance reporting by councils in our proposed performance audit, which we discuss at the end of this Part.

Engaging with communities and collaboration with other councils

6.45

Several councils are collaborating with other councils in their regions to share climate-related information and approaches. For example, the eight councils in the Manawatū-Whanganui region signed a memorandum of understanding in December 2020 about how they will collaborate on climate change resilience and emissions reductions in their region.40

6.46

The councils formed a Climate Action Joint Committee in early 2021 to guide their climate action activities, including completing a regional risk assessment to identify issues that most urgently need attention.

6.47

Councils are also taking action to raise community awareness of climate change mitigation and adaptation challenges and are working with communities and other partners and groups on solutions.

6.48

Several councils confirmed additional funding for climate-related projects or work in response to feedback during the consultation on the long-term plans that the community wanted their council to do more.

6.49

For example, Nelson City Council received 147 submissions on climate change, with most supporting the Council being proactive in addressing the challenges of climate change. Some urged the Council to progress as fast as possible and prioritise dealing with climate change over other spending. Ten submitters were opposed to work in this area. The Council elected to proceed with its proposed changes.

6.50

Whangarei District Council observed that it saw a majority of submitters asking the Council to do more about climate change and sustainability. Elected members responded to this by confirming the $3.7 million of new funding that we consulted on. The Council also increased the contestable fund by $100 thousand per year for community waste minimisation projects and clean ups.41 The Council notes that the funding of $3.7 million was aligned to its capacity to deliver the projects in both the adaptation and mitigation realm. This includes delivery of priority actions within the Te Tai Tokerau Climate Adaptation Strategy, which is a region-wide strategy developed collaboratively and adopted in 2022 by the four Northland councils.

Integration

6.51

The statutory purposes of a long-term plan include integrated decision-making, taking a long-term focus for the council's decisions and activities, and being accountable to communities.42

6.52

Climate change is an issue with long-term implications, and it needs to be integrated into the council's processes, plans, and strategies. Communities that seek climate action have an interest in how their council accounts for its climate-related performance.

6.53

Several long-term plans reflected the council's strategy to integrate climate change into its planning and decision-making or embed climate change considerations into all decisions.

6.54

For example, Hawke's Bay Regional Council observed that:

Climate change is therefore a focus in all of our planning and decision-making with climate change projections, adaptation and mitigation a key component of this Long Term Plan.43

6.55

Waitaki District Council disclosed that:

Using the best available information, climate change considerations are becoming a core part of our planning. The impacts of climate change are being considered in our work on strategies and plans, including this plan, the AMP's, our Financial Strategy, our Coastal Roads Strategy and our District Plan, and through design and construction standards, identification of hazards, and redundancy and mitigation (such as insurance) over the life of the Long-Term Plan.44

Some councils have reflected a sense of urgency and priority

6.56

Councils that declared climate emergencies tend to give a sense of urgency and priority to climate action in their long-term plans. This is reflected in statements in their long-term plans.

6.57

Nelson City Council said that:

Responding to climate change is our biggest global challenge. We have less than a decade to accelerate our emissions reductions to avoid the full effects of global warming.45

6.58

Porirua City Council said that:

To accelerate our response to climate change, Council agreed to invest an additional $6 million during years 2022/23 and 2023/24 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from council facilities, reduce organic waste going to the landfill and accelerate the transition of Council's fleet to electric vehicles where we can.46

6.59

Wellington City Council said that:

We are in a climate and ecological emergency and we need to take action now to adapt to the changing climate, and to lessen the extent of the impacts through supporting the city to radically lower emissions. In addition, the city has ongoing ambitions to protect and enhance the city's indigenous biodiversity, outlined in Our Natural Capital – Wellington's Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, that will need continued Council investment.47

Climate action plans

6.60

Some councils are increasingly referring to climate action as well as climate change, and several councils have adopted or are working on dedicated climate action plans.

6.61

In 2020/21, we carried out a preliminary review of climate action planning by councils before beginning the long-term plan audits. We found that 21 councils had a dedicated climate action plan or a similar document, such as a sustainability plan or climate change strategy, policy, or roadmap setting out needed actions.

6.62

A further 19 councils had some documentation relevant to climate change (for example, a collection of actions without an overarching plan, an environmental scan, or principles for addressing climate change). We could not find any publicly available climate action plans or similar documents for the remaining 38 councils.

6.63

For this report, we considered the climate action plans of councils that have declared a climate emergency. We are aware that some councils that have not declared emergencies also have climate action plans.

6.64

Some of the councils that have declared a climate emergency acknowledge that they are at the early stages of taking climate action. Not all councils that have declared a climate emergency have adopted a climate action plan, but most of those have draft action plans or are developing them.

6.65

We provide examples of three councils that have more developed action plans.

6.66

Queenstown-Lakes District Council consulted on a second iteration of its climate action plan during the 2022/23 annual plan process. The Council aims to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and to be resilient to the local impact of climate change throughout the whole district. The Council uses a climate reference group and its audit and risk committee to guide its climate-related actions.

6.67

Auckland Council adopted a climate action plan in December 2020 for itself and the Council group. The climate action plan is comprehensive and well advanced compared to other councils, but the Council says that more needs to be done. The Council consulted on a new "climate action targeted rate" in its 2022/23 annual plan process to further support the actions in its climate action plan, particularly in the transport sector. The proposed rate would raise $574 million during a 10-year period.

6.68

Wellington City Council's climate action plan sets the city's target of net zero carbon by 2050. The Council plans to invest $47 million in climate action during the period of the 2021-31 long-term plan, including to measure its emissions, engage residents, and develop more climate action initiatives in partnership with a range of stakeholders. The Council is also developing a framework to measure progress and be accountable for emissions reductions.

Climate justice and a focus on transition

6.69

Some councils are considering the equity or social justice aspects of climate change, as a general recognition that some communities may be affected by climate change and transitioning to a low carbon economy more than others.

6.70

For example, Dunedin City Council's long-term plan describes the Council's work to build resilience and identify opportunities and plan for long-term adaptation for South Dunedin, a low-lying, highly populated area of the city. Dunedin's mayor stresses the importance of the need for "ensuring a just transition to a safer climate future" in his introduction to the long-term plan.48

6.71

Auckland Council's climate action plan considers equity, climate change as a social issue, and climate change through a te ao Māori perspective.49

6.72

An "equitable transition" is one of the five underpinning principles of the Government's Emissions Reduction Plan. This could provide useful guidance for councils thinking about equity in their climate action planning.50

Climate change response as a new activity

6.73

Porirua City Council created a new "climate change response" activity as one of its main groups of activities, with associated outcomes and performance measures and three focus areas – mitigation, adaptation, and transition.

6.74

The Council established the new activity to guide and direct its response to climate change. The activity provides expert advice to the Council, identifies and manages key projects that address specific climate-related issues, and supports other groups within the Council that are working on climate-related issues.

6.75

The Council has introduced the following time-based measures, with a target of 100% completion on time:

- 2021/22 – develop business cases for actions to reduce the Council's greenhouse gas emissions;

- 2022/23 – greenhouse gas targets are adopted by the Council; and

- 2023/24 – the Council's greenhouse gas mitigation plan is developed and being implemented. Adaptation planning is under way with the community.51

Use of climate guidance and reporting frameworks

6.76

Some councils are using climate-related guidance or membership organisations to assist their thinking or are applying reporting frameworks on a voluntary basis.52

6.77

For example, Greater Wellington Regional Council has joined CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), a charity that runs a global disclosure system to help entities and regions manage their environmental impacts.

6.78

The Council is also drawing on the recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).53 This is an international organisation set up to develop voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for organisations.

6.79

Auckland Council has voluntarily adopted the TCFD's climate reporting framework. The Council produces a separate volume of its annual report about climate-related risks and opportunities for the Auckland Council group.

6.80

The Council considers that identifying and disclosing its climate-related financial risks is key to providing a transparent view to improve its stakeholders' understanding of the financial implications associated with climate change.

6.81

The Council said that applying TCFD's recommended disclosures has meant making fundamental changes to embed climate risk management into its governance structures, strategic, and financial planning processes.

Climate change opportunities

6.82

Some councils are also considering opportunities associated with climate change. The TCFD's guidance states that efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change also produce opportunities for organisations – for example, resource efficiency and cost savings by adopting low-emission energy sources, access to new markets, and building resilience along the supply chain.

6.83

Greater Wellington Regional Council describes climate-related opportunities in transport, including the potential to find innovative ways to further decarbonise its public transport fleet (bus, rail, and ferry) and implement nationwide electronic ticketing for public transport.54

6.84

Nelson City Council sees many opportunities in its climate change response, including restoring biodiversity, improving water and soil quality, building sustainable urban environments, and promoting healthy lifestyle choices and connected communities in a more liveable city.55

We are proposing further work to consider climate action by councils

6.85

It is encouraging to see that all councils are thinking about climate change in their 2021-31 long-term plans, and that some have identified climate action as a strategic priority and recognise the urgency to take action.

6.86

This is a marked improvement from the 2018-28 long-term plans. A notable change is that several councils have dedicated climate action plans and resources or are working on them. Councils that want to develop climate action plans have plenty of good examples and experience from other councils to draw on, as well as guidance and direction from international frameworks such as TCFD or the Government's 2022 Emissions Reduction Plan.

6.87

It is encouraging to see councils beginning to put performance targets and measures into their plans so that they can assess and report on progress and be accountable to their communities, including to those who want more climate action.

6.88

Climate action and reporting is a developing area. Councils that have included climate-related targets and measures into their long-term plans will be among the first public organisations to formally report their progress with climate actions. Councils that have included relevant metrics as part of their performance measurement framework will be well positioned to report on their contribution to the Government's emissions reduction targets.

6.89

The discipline of long-term planning is well established in local government. Councils have good experience in considering future effects and scenarios about matters that could have a significant impact on their operations and in forecasting related costs. This will be helpful for more formal climate-related reporting should such requirements be established for councils.

6.90

As councils develop their next long-term plan, they could consider the opportunity to take a strong leadership role in climate action in their district or region. The current local government reforms could provide scope or opportunity for councils to take more climate actions in the future.

6.91

We intend to consider climate action by councils in more depth in a performance audit in 2022/23.56 This assessment of climate actions set out in the 2021-31 long-term plans and our performance audit will provide a baseline for comparison with future long-term plans. We will use it to measure how councils are progressing with climate actions over time and to track any increasing urgency and activity.

30: As implemented by the 2019 "zero carbon" amendments to the Climate Change Response Act 2002.

31: Ministry for the Environment (2022), Te hau mārohi ki anamata: Towards a productive, sustainable and inclusive economy.

32: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans, Part 6.

33: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Insights into local government: 2019, Part 5.

34: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans, page 39.

35: In the 2019 calendar year, 16 councils declared climate emergencies. Whanganui District Council declared a climate emergency on 11 February 2020.

36: Office of the Auditor-General (2011), Local government: Results of the 2009/10 audits, Part 4.

37: Waitaki District Council (2021), 2021-2031 Long term plan, page 326.

38: Chatham Islands Council (2021), Long term plan 2021-2031, page 66.

39: Climate Change Response Act 2002, as amended by the Zero Carbon legislation in 2019.

40: Horizons Regional Council (2020), Manawatū-Whanganui climate change action plan towards a climate-resilient region.

41: Whangarei District Council, Long term plan 2021-31, Volume 1, page 10.

42: Section 93(6) of the Local Government Act 2002.

43: Hawke's Bay Regional Council, Time to Act – Kia Rite! 2021-2031 Long term plan, page 12.

44: Waitaki District Council, 2021-31 Long term plan, page 325.

45: Nelson City Council, Your wellbeing, Nelson's future – Oranga Tonutanga: Nelson's long term plan 2021-2031, page 26.

46: Porirua City Council, Porirua – our people, our harbour, our home: Long-term plan 2021-51, page 11.

47: Wellington City Council, Tō mātou mahere ngahuru tau: Our 10-year plan, Volume 1, page 21.

48: Dunedin City Council, Tō tātou eke wakamuri – The future of us: 10 year plan 2021-31, page 2.

49: Auckland Council (2020), Te Tāruke-ā-Tāwhiri: Auckland's climate plan, pages 11-12.

50: Ministry for the Environment (2022), Te hau mārohi ki anamata: Towards a productive, sustainable and inclusive economy, chapter 3.

51: Porirua City Council, Porirua – our people, our harbour, our home: Long-term plan 2021-51, page 96.

52: International guidance on climate reporting is available, including from the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. This guidance is being used to develop climate-related reporting requirements for certain New Zealand entities that operate in financial markets, including a small number of public sector entities.

53: For more information about the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, see www.fsb-tcfd.org.

54: Greater Wellington Regional Council, The Great Wellington Regional story – Ko Te Pae Tawhiti: Long Term Plan 2021-2031, page 66.

55: Nelson City Council, Your wellbeing, Nelson's future – Oranga Tonutanga: Nelson's long term plan 2021-2031 on the Nelson City Council's website, page 26.

56: See Office of the Auditor-General (2022), Annual plan 2022/23 at oag.parliament.nz.