Part 2: The financial strategies adopted by councils and their impact on rates and debt

2.1

In this Part, we discuss:

- what financial strategies are and how effective they were;

- the rates limits that were set in councils' financial strategies and what this meant for proposed rates to be set throughout the sector; and

- the debt limits that were set in councils' financial strategies and how councils are looking to manage debt.

2.2

We also discuss why some of the financial assumptions that councils made affected the audit reports we issued.

What is a financial strategy?

2.3

The Local Government Act 2001 (the Act) sets out the purpose and required content of the financial strategy. Section 101A(2) states that the purpose of the financial strategy is to:

- facilitate prudent financial management by the local authority by providing a guide for the local authority to consider proposals for funding and expenditure against; and

- provide a context for consultation on the local authority's proposals for funding and expenditure by making transparent the overall effects of those proposals on the local authority's services, rates, debt, and investments.

2.4

The financial strategy is a mix of forecast information about what could have a significant financial effect on the council (such as changes in population or land use), expected capital expenditure in significant areas, and disclosures about the financial parameters that the council will operate in (limits on rates increases, borrowing, and targeted returns for financial investments).

2.5

The financial strategy is a critical part of the long-term plan. Along with the council's infrastructure strategy, it provides the strategic direction and the underpinning context for the long-term plan. Taken together, the financial and infrastructure strategies provide the reader with a sense of the costs, risks, and trade-offs that underpin the development of the expenditure programmes in the long-term plan.5

How effective were the financial strategies?

2.6

Councils should clearly explain their financial strategies to their communities by summarising what happened in the past, describing the present situation and challenges, and setting goals for the future (including why these are desirable and important).

2.7

For readers of the long-term plan to meaningfully assess the prudence of councils' financial management, the financial strategy must be clear about its goals and trade-offs and be presented in a concise way.

2.8

In our view, Hamilton City Council, Tasman District Council, and Greater Wellington Regional Council had effective financial strategies.

2.9

Hamilton City Council's financial strategy, which is seven pages long, is clear, concise, and easy to read. The Council highlights as a key challenge the unprecedented growth the city is experiencing and the increased pressure this has placed on infrastructure and services.

2.10

This provides a good link between the Council's infrastructure and financial strategies. The Council then explains how it has adapted the financial strategy to respond to these challenges, including by increasing the debt-to-revenue limit. There is also a clear description of the risk of the growth assumptions being higher or lower than planned and what the implications for the strategy would be.

2.11

Tasman District Council's financial strategy, which is 17 pages long, is a good example of "telling the story" to the community. It has a clear beginning (setting the scene), middle (explaining the current challenges), and end (describing the destination and its importance and impact – for example, the impact on drinking water quality and level of service).

2.12

The Council uses effective headings such as "The lay of the land", "What are our goals?", and "What's the plan?" to help the reader engage with the strategy. The Council also provides a good description of land use and the expected changes caused by growth.

2.13

Greater Wellington Regional Council's financial strategy, which is 19 pages long, clearly states its guiding principles. The Council clearly explains its current challenges, with a particular focus on climate change. There are good links to the Council's infrastructure strategy. Overall, the financial strategy is presented in a way that is easy for the reader to engage with.

2.14

In our view, presenting a clear and concise strategy, then adding any other required disclosures that have not already been covered, will produce a more effective financial strategy.

2.15

In our previous audits of long-term plans, we commented that presenting financial strategies in a clear and concise way would be more effective. Therefore, in our report on matters arising from the 2018-28 long-term plans,6 we set councils the challenge of producing clear and concise financial strategies that were no longer than five pages in their 2021-31 long-term plans.

2.16

We have reviewed the financial strategies in the 2021-31 long-term plans to see whether councils met this challenge. Although the Act sets out the minimum requirements of a financial strategy, some councils chose to provide additional information in the long-term plan's financial strategy section.

2.17

This additional information may include the financial prudence graphs or combining the financial and infrastructure strategies in the same section.7 This makes it more difficult to directly compare the length of financial strategies between councils.

2.18

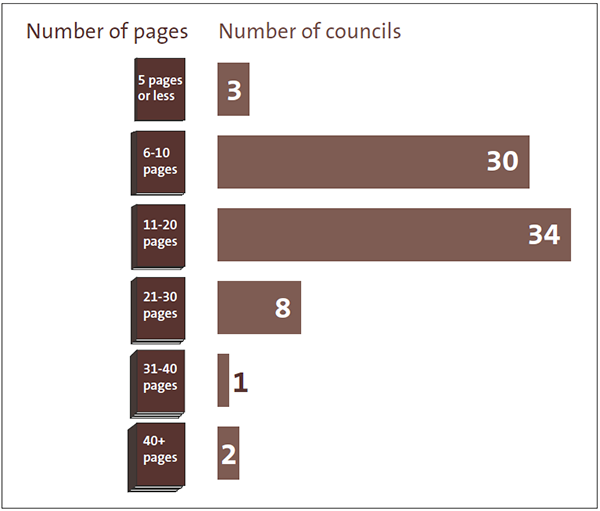

However, because not many councils include the financial prudence graphs and infrastructure strategies, the overall analysis gives us a reasonable idea of the length of financial strategies. Figure 2 gives more information on the page count of councils' financial strategies.

Figure 2

The length of councils' financial strategies in their 2021-31 long-term plans

2.19

The average length of all financial strategies was 14 pages. Thirty-three councils had financial strategies that were 10 pages or fewer, and 67 councils had financial strategies that were 20 pages or fewer. This indicates that councils tried to present the necessary information to their communities in a clear and concise manner.

The rates limits set by councils in their financial strategies

2.20

Section 101A(3)(b)(i) of the Act requires a council's financial strategy to include a statement about the council's quantified limits on rates increases. Some councils continue to set a total limit for rates (for example, by stating that rates would not exceed a certain percentage of total revenue), although the Act no longer requires this.

2.21

Councils set their own rates increase limits, which may be the same for each of the 10 years or an average of the 10 years of the plan. Alternatively, limits may vary year on year.

2.22

Slightly more than one-third of councils linked their rates increase limits to the local government cost index.8 Of these councils, most set a limit of local government cost index plus a single specified percentage (ranging from 2% to 9%). Most councils with rates increase limits not tied to the local government cost index had a specified percentage limit or a range that was generally tied to the council's actual results for the previous year.

2.23

Several variables are also involved – for example, whether the limits apply to general rates only or whether they also apply to targeted rates. The limits may also specifically include matters such as inflation, growth, water by meter, and rates penalties. This makes it difficult to directly compare councils. With this in mind, we have reviewed the information about rates increases in councils' financial strategies.

2.24

Porirua City Council, Rotorua Lakes Council, and Buller District Councils are among those setting the lowest rates increase limits (at 1.6%, 2%, and 2.2% respectively). For the 10 years covered by their long-term plans:

- Buller District Council's limit remains at 2.2% during all 10 years of the plan;

- Porirua City Council's limits range from 1.6% in 2029/30 to 7.6% in 2021/22; and

- Rotorua Lakes Council's limits range from 2% in 2026/27 to 9.2% in 2021/22.

2.25

However, Buller District Council is proposing to breach its limits in the first four years of its long-term plan.

2.26

Otago Regional Council, Wellington City Council, and Environment Southland are among those setting the highest rates increase limits (at 49%, 27.5%, and 20% respectively). All have quite large ranges in their limits (at 6%-49%, 3%-27.5%, and 5%-20% respectively).

2.27

In some years, Wellington City Council's limits are significantly higher than its forecast rates increase. For example, year one of the long-term plan has a 27.5% limit against a 14% forecast, year four has a 25.2% limit against a 6.5% forecast, and year five has a 20.2% limit against a 2% forecast.

2.28

As a subsector, regional councils set the highest rates increase limits largely due to the need to increase compliance with government standards. They have four of the five highest limits.9 However, a ratepayer pays a significantly lower amount of rates to a regional council than to a territorial authority. Appendix 2 lists which councils are in each subsector.

2.29

This means that the impact of higher rates increase limits for a regional council may not be as significant for an individual ratepayer as higher rates increase limits for a territorial authority.

2.30

Like Buller District Council, 20 other councils have set the same rates increase limit during all 10 years of the long-term plan. Of the remaining 57 councils, the general trend for most (46 councils) is to set the highest rates increase limits in the earlier years of the plan and for these to decrease during the 10 years of the plan.

2.31

Most of the limits are not substantially different to the movements forecast in the long-term plans. Some councils have set their forecast rates increases equal to the limit set for some or all years of the plan. This suggests that the limits may be restraining actual practice in setting rates, or it could mean that limits are set to fit around the financial forecasts – and so do not really function as a true limit.

2.32

Although councils set their own rates increase limits (see paragraph 2.21), 30 councils forecast that they will breach their rates increase limits in at least one year of the long-term plan. Central Hawke's Bay District Council and Greater Wellington Regional Council forecast that they would breach their limits in seven years of their plans.

2.33

It appears that these two councils have opted to keep their prescribed limits, despite knowing they are likely to be breached in some years. These councils have included explanations for this in their long-term plans.

2.34

Councils should be clear about what limits they have set. Importantly, they should explain why using that specific limit to assess their financial health or prudence is appropriate.

Effective financial strategies should clearly disclose the rates increase limit set and why the limit is prudent.

2.35

Although Christchurch City Council was not expecting to breach its rates increase limits, it described the limits as "soft". This means that the Council could choose to exceed them if it could explain why it would be prudent to do so. This implies that the Council is treating the limit more like a guideline that can be flexible if needed. The Council has taken this approach because it recognises that the Christchurch earthquake rebuild and changing economic environment could result in a change in forecasts and ultimately the level of rates the Council will need to set.

2.36

Although councils forecast to keep to the limits they set in most instances, many ratepayers cannot relate the increases in their rates invoice from one year to the next to the rate increase limits set by their council. This is because rates increases are generally reported as an increase in total revenue, where individual ratepayers will pay more or less depending on factors such as rating policies and changes to differentials.

What are the proposed rates to be set for the sector in long-term plans?

Rates as a percentage of total council revenue remains consistent

2.37

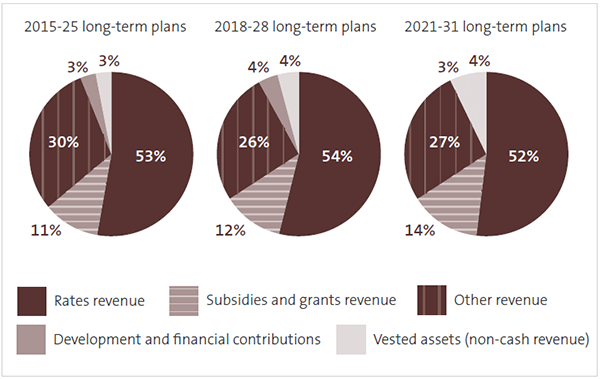

The total amount of councils' revenue forecast to be received from rates has increased in the last three long-term plan rounds (2015-25 long-term plans: $65.3 billion; 2018-28 long-term plans: $77.8 billion; and 2021-31 long-term plans: $98.7 billion). However, the percentage of revenue received from rates has remained relatively constant at between 52% and 54% (see Figure 3).

2.38

Individually, the average percentage of forecast revenue made up by rates revenue during the 2021-31 period varies from 7% (Chatham Islands Council, which has fewer than 1000 residents and rateable units and relies heavily on central government funding for its operational and capital expenditure) to 81% (Kawerau District Council).

2.39

Three councils have forecast rates revenue that makes up less than 40% of their total income. For 14 councils, forecast rates revenue makes up more than 70% of their total income during the same period.10

2.40

Some councils said in their financial strategies that they will actively seek to minimise their reliance on rates to fund their operational expenditure by promoting other revenue sources, such as government grants, sponsorship, and "user pays" policies.

Figure 3

The composition of total revenue by revenue type for the 2015-25, 2018-28, and 2021-31 long-term plans

Rates revenue is the largest forecast revenue stream, making up more than 50% in each long-term plan round. The next highest categories are other revenue, making up between 26% and 30% of forecast revenue, and subsidies and grants revenue, making up between 11% and 14%. "Other revenue" includes council fees and charges revenue, and investment revenue such as interest and dividends.

2.41

However, other councils are taking the opposite approach. Hawke's Bay Regional Council has signalled an increase in rates as a percentage of total revenue from 50% to 60% in its 2021-31 financial strategy to reduce its reliance on investment income. Rotorua Lakes Council said that it is prudent to rely on rates (rather than other revenue sources) because it is a stable revenue base. It also said that the impact of Covid-19 restrictions on other revenue streams had proven this.

2.42

As mentioned in paragraphs 1.22 to 1.35, councils' long-term plans were affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. This included councils needing to decide whether to continue rates relief initiatives they applied in 2020/21.

2.43

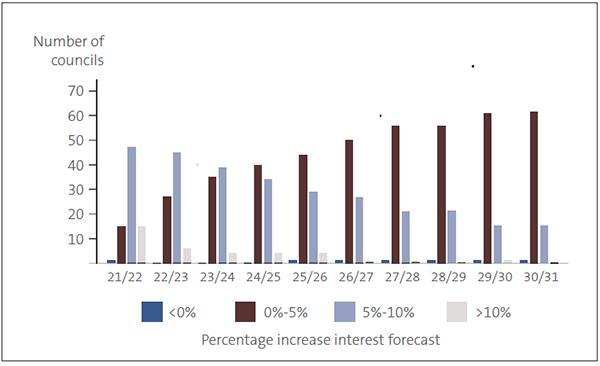

Figure 4 shows the spread of increases in rates forecast by councils in their 2021-31 long-term plans. Most councils forecast to increase their rates by between 5% and 10% in 2021/22, 2022/23, and 2023/24. Fifteen councils forecast to increase their rates by more than 10% in 2021/22. From 2024/25, most councils' forecast rates increases were between 0% and 5%.

Figure 4

The number of councils forecasting to increase their rates for 2021/22 to 2030/31 and the percentage increase forecast

The graph shows how many councils forecast to increase their rates by certain levels for 2021/22 to 2030/31. We have categorised forecast rates increase by less than 0%, 0% to 5%, 5% to 10%, and more than 10%. The largest categories are 5% to 10% (for 2021/22 to 2023/24) and 0% to 5% (for the other financial years).

2.44

The general trend is that most councils have forecast their highest rates increases to be in years 1-3, and rates will decrease during the 10 years of the plan. There appears to be a bias to the shorter term compared with the long term because of an increased level of uncertainty.

2.45

This creates certain expectations in the community about what future rates will look like. However, history shows us that rates increases seldom stay as low as forecast.

2.46

Given that most council spending is on infrastructure, this could suggest that councils are being overly optimistic with their assumptions about the level of future investment or reinvestment in assets needed in the later years of the plan.

2.47

It is reasonable for the community to understand that there is less certainty in the later years of the plan and that new projects (which are not yet known) will need funding, possibly through rates.

Councils need to make robust assumptions over the 10 years of the long-term plan to provide reliable and transparent forecasts for expected future rates increases.

2.48

However, communities could lose trust and confidence in a council if they feel that their expectations of rates increases have not been met. In our view, councils need to continue to focus on the robustness of their planning during the full 10 years of the long-term plan.

What borrowing limits did councils set in their financial strategies?

2.49

As well as requiring a council's financial strategy to set a limit on rates increases, section 101A(3)(b)(i) of the Act also requires a council's financial strategy to include a statement about the council's quantified limits on borrowing. Councils can choose what limits to set. Many councils apply multiple limits.

2.50

The limits set in accordance with the Act should not be confused with debt covenants or limits set by lenders. For example, the New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA) applies debt limits to council borrowers.11

2.51

We have previously encouraged councils to consider whether the debt limits they set are a strategic control on financial practice. A limit on borrowing needs to reflect the council's risk appetite. There is a risk that some councils applied the LGFA debt limits without considering how well these limits fit their own situation and that some councils set limits well above the actual position forecast in the long-term plan.

2.52

In our report on matters arising from the 2015-25 long-term plans, we analysed the range of debt limits that councils used.12 Although the LGFA limit was the most commonly used, we found that councils were using up to five other debt limits. We have repeated some of this analysis for the 2021-31 long-term plans.13

2.53

Figure 5 shows the range of councils' borrowing limits and how this compares to our analysis of the 2015-25 long-term plans. Councils can have more than one borrowing limit.

2.54

Some results are similar to the 2015 limits. Given that councils are now taking on more debt than ever before, the increases are expected.

Figure 5

Range of councils' borrowing limits

| Highest in limit range | Lowest in limit range | Average limit | Number of councils using this limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt as a % of operating income | 300% (2015: 275%) |

40% (2015: 50%) |

193% (2015: 162%) |

68 (2015: 45) |

| Debt as a % of assets | 50% (2015: 20%) |

10% (2015: 10%) |

21% (2015: 16%) |

6 (2015: 8) |

| Debt as a % of rates income | 280% (2015: 200%) |

280% (2015: 25%) |

280% (2015: 160%) |

1 (2015: 6) |

| Debt as a % of equity | 20% (2015: 28%) |

10% (2015: 5%) |

18% (2015: 18%) |

4 (2015: 8) |

| Maximum debt per capita or rateable property | $8,000 (2015: $5,788) |

$500 (2015: $500) |

$4,167 (2015: $2,782) |

3 (2015: 12) |

| Maximum total debt | $250 million (2015: $590 million) |

$15 million (2015: $12 million) |

$103 million (2015: $181 million) |

7 (2015: 10) |

2.55

The highest maximum total debt limit has decreased from $590 million in 2015 to $250 million in 2021. However, because only seven councils are using this limit (compared to 10 in 2015), it is not indicative of the debt trends we see throughout the sector.

2.56

The results for the debt as a percentage of rates income also look quite different. However, because only one council used this limit in 2021, the data is skewed.

How much are councils proposing to borrow?

Councils are forecasting steep increases in their debt levels

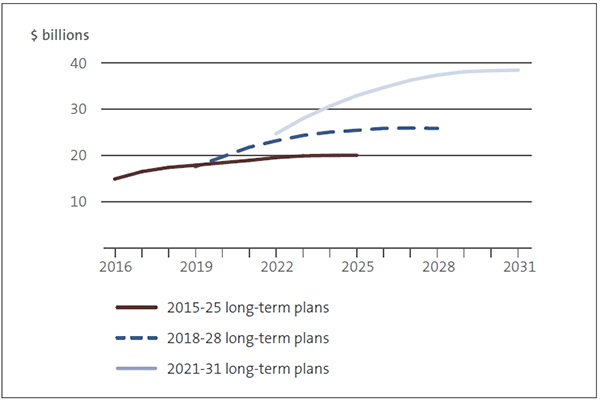

2.57

Figure 6 shows a significant increase in councils' forecast borrowing in the 2021-31 long-term plans compared with the 2018-28 and 2015-25 long-term plans. The level of forecast borrowing in the current long-term plan is the highest it has ever been.

2.58

If the forecasts in the 2021-31 long-term plans are met, councils will have borrowed about $11 billion more by 2028 than they had forecast three years ago. Debt is forecast to be more than $38 billion by the end of the long-term plan forecast period. By comparison, councils had forecast that debt would peak at about $25 billion in their 2018-28 long-term plans.

Figure 6

Comparison of debt forecasts from the 2015-25, 2018-28, and 2021-31 long-term plans

The graph presents the forecast debt levels for councils, as presented in the 2015-25, 2018-28, and 2021-31 long-term plans. In the 2015-25 long-term plans, councils forecast debt to increase from $14.9 billion in 2015/16 to $20.0 billion in 2024/25. In the 2018-28 long-term plans, councils forecast debt to increase from $17.6 billion in 2018/19 (about the same amount as was forecast in the 2015-25 long-term plans) to $25.9 billion in 2027/28. In the 2021-31 long-term plans, councils forecast debt to increase from $24.7 billion in 2021/22 (about the same amount as was forecast in the 2018-28 long-term plans) to $38.4 billion in 2030/31.

2.59

Figure 7 shows that, when we analysed by type of council, all subsectors showed a similar increase in debt levels (see Appendix 2 for the list of subsectors). Councils' total debt is significantly influenced by Auckland Council's debt, which is forecast to reach $16.3 billion by 2031. This makes up 42% of councils' total debt.

Figure 7

Peak debt forecasts by council subsector in the 2021-31 long-term plans, compared with the 2018-28 long-term plans

| Subsector | 2021-31 long-term plan | 2018-28 long-term plan |

|---|---|---|

| Auckland | $16.3 billion in 2030/31 $15.5 billion in 2027/28 (when peaks in 2018-28 long-term plan) |

$13.1 billion in 2027/28 |

| Metro | $12.2 billion in 2030/31 $11.8 billion in 2027/28 (when peaks in 2018-28 long-term plan) |

$7.6 billion in 2027/28 |

| Provincial | $7.2 billion in 2028/29 $5.8 billion in 2023/24 (when peaks in 2018-28 long-term plan) |

$4.0 billion in 2023/24 |

| Regional | $1.9 billion in 2028/29 $1.7 billion in 2025/26 (when peaks in 2018-28 long-term plan) |

$1.1 billion in 2025/26 |

| Rural | $1.0 billion in 2027/28 $0.9 billion in 2024/25 (when peaks in 2018-28 long-term plan) |

$0.6 billion in 2024/25 |

2.60

Increased borrowing means that some councils are approaching (or have forecast that they will exceed) their debt limits. The risk is that councils approaching or exceeding their debt limits will start to exhaust their ability to borrow and will have to use operational funding to continue to reinvest in and increase their assets. Otherwise, levels of service may have to decrease. When a council is close to their borrowing limit, they have less ability to borrow to deal with unexpected events, such as natural disasters.

2.61

It is important that councils set debt limits that are at an appropriate level for the right reasons and are tailored to a council's specific circumstances. To be financially prudent, all drivers of a council's debt limits need to be considered, including revenue. Some councils have experienced decreases in revenue as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the consequent lowering of those councils' borrowing limits.

Councils with large debt levels will need to closely monitor changes in interest rates

2.62

Increases in interest rates also pose risks to councils. Interest rates have been low in recent times. However, interest rates are now expected to increase and could be higher than councils forecast in their 2021-31 long-term plans.

Councils, particularly those with significant debt levels, need to closely monitor interest rates and ensure that they have sound treasury management practices.

2.63

In their 2021-31 long-term plans, councils have forecast interest expenses and interest rates to be far lower than in the 2015-25 and 2018-28 long-term plans. For example, in 2021/22, councils forecast $0.8 billion of interest expense in the 2021-31 long-term plans. By comparison, the 2015-25 and 2018-28 long-term plans forecasted between $1.1 and $1.2 billion of interest expenditure. As a proportion of debt, interest expenditure ranges between 3.1% and 3.3%. In the 2018-28 and 2015-25 long-term plans, ranges were 5.0% to 5.4% and 5.5% to 5.9% respectively.

2.64

Councils may find it increasingly difficult to fund the cost of borrowing. To manage this risk, councils, particularly those with significant debt levels, will need to closely monitor interest rates and ensure that they have sound treasury management practices.

Why some of the financial assumptions councils made affected the audit reports we issued

2.65

In preparing their long-term plans, councils need to make assumptions about how they will fund their activities. Although a significant amount of this funding comes from rates and debt, there are other sources of funding, including subsidies and grants (see Figure 3).

2.66

When councils make significant funding assumptions, we expect these assumptions to be adequately supported – for example, by having an agreement or contract already in place or by taking active steps to secure funding. We also consider whether a council was able to secure similar funding in the past.

2.67

Additionally, if a council assumes that it will receive funding from central government, we expect there to be relevant appropriate funds available. When there were no such known funds, we considered the assumption to be unreasonable.

2.68

Without enough support, there is a risk that the funding may not eventuate. This could affect a council's ability to deliver a stated level of service. It could also mean that a council will need to use alternative funding sources, such as rates or debt.

A council’s financial strategy should clearly disclose the reliance the council places on alternative funding sources and the risks of those sources not eventuating.

Qualified audit opinions because of unreasonable funding assumptions

2.69

For six councils, we determined that the funding assumptions made were unreasonable. This was because they were unable to provide our auditors with the appropriate level of evidence to support the assumption in their long-term plan that a significant portion of funding would be provided from an external source.

2.70

Three of the six qualified audit opinions we issued related to the councils' assumptions that they would receive central government or other external funding.14 These three councils also received qualified audit opinions on their long-term plan consultation documents for the same reason.

2.71

The other three qualified audit opinions we issued also related to central government funding, specifically the assumption that the councils would receive funding from Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency (Waka Kotahi).15

2.72

We usually consider this assumption to be reasonable because Waka Kotahi is a known source of local government funding for roading and public passenger transport activities. However, these councils continued to assume a certain level of funding would be received after Waka Kotahi confirmed that the level of funding would be lower. We therefore considered the funding assumptions to be unreasonable.

2.73

The timing of some funding decisions and announcements can be a challenge for councils when preparing their long-term plans. For example, budgets for central government are generally announced in May, but councils consult on the proposed content of their long-term plans before then.

2.74

One of the more significant challenges for councils is the timing of when Waka Kotahi finalises its National Land Transport Programme. This is usually in August, which is after the statutory deadline for councils to adopt their long-term plans. Waka Kotahi provides the largest source of subsidy funding to the local government sector as a whole.

2.75

Historically, in preparing their long-term plans, councils have assumed that they would receive similar levels of financial assistance rates from Waka Kotahi that they received in the past. This was the assumption that most councils applied in preparing the 2021-31 long-term plans.

2.76

However, in April 2021, when most councils were consulting on the proposed content of their long-term plans, Waka Kotahi noted that funding requests for continuous programmes were significantly higher than funding provided for in the previous National Land Transport Programme. Waka Kotahi also stated that, overall, funding for the 2021-24 National Land Transport Programme was highly constrained.

2.77

In May 2021, Waka Kotahi provided many councils with information about indicative allocations for some of the programmes it funds. In some instances, the indicative amounts were materially different to what councils had forecast.

2.78

In these situations, we considered it appropriate that the council update its forecast to reflect the indicative funding announced by Waka Kotahi.

2.79

Making a change this late in the long-term planning process is challenging because it requires the council to consider alternative ways of funding this work. If there are no alternative funding options, the council will need to consider the implications of deferring work. In some cases, this could be more costly in the long term because the process involves long-term asset management plans, which inform the appropriate level of expenditure.

2.80

Where councils did not update its forecast to reflect the indicative funding announced by Waka Kotahi, and the difference between what councils were forecasting and the indicative funding announced by Waka Kotahi was materially different, we qualified our audit opinion. In some cases, the councils were looking to continue to engage with Waka Kotahi to secure this funding in the future.

In our view, there remains a need for central and local government to consider how they can understand and support each other’s planning cycles.

Palmerston North City Council received an adverse audit opinion

2.81

One of the two adverse audit opinions we issued (see Figure 1) related to the funding and financing assumptions that Palmerston North City Council made. We also issued an adverse audit opinion on the Council's long-term plan consultation document for the same reason.

2.82

We determined that Palmerston North City Council's long-term plan did not meet its statutory purpose because it did not provide an effective basis for long-term integrated decision-making or co-ordination of the Council's resources and accountability to its community.

2.83

This was because, in our view, the underlying information and assumptions in the long-term plan were unreasonable and inconsistent with Palmerston North City Council's financial strategy.

2.84

Palmerston North City Council included an upgrade to its wastewater treatment plant from year 4 of its long-term plan. When the Council included the upgrade in its long-term plan, there was no certainty about the proposed three waters reforms, including whether the Council would be financially responsible for the upgrade. This meant that the Council made the decision, in the interests of transparency, to include the anticipated costs in its long-term plan.

2.85

However, we considered that the underlying information and assumptions that Palmerston North City Council's long-term plan was based on were inconsistent with its own financial strategy.

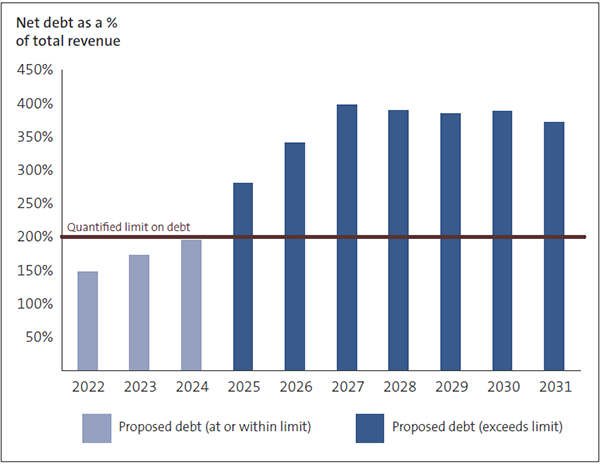

2.86

Palmerston North City Council's financial strategy caps the Council's debt at 200% of revenue (see Figure 8). With the inclusion of the wastewater treatment plant upgrade, the forecasts in the plan showed that the Council expected to exceed its own debt cap after year 4 of the long-term plan (and was forecasting to exceed the debt limits set by the LGFA after year 5).

2.87

Palmerston North City Council also disclosed in its long-term plan that it was highly unlikely that lenders would be prepared to lend the amounts that were in the underlying information.

Figure 8

Palmerston North City Council's proposed debt compared to its debt affordability benchmark

Palmerston North City Council's net debt limit was set at 200% of total revenue. The Council forecast to comply with its net debt limit for 2021/22, 2022/23, and 2023/24. For the other seven years, the Council forecast to breach its net debt limit. From 2025/26 to 2030/31, the Council was forecasting net debt to be above 300% of its total revenue.

Source: Palmerston North City Council 10-year plan, 2021-31.

2.88

In our view, Palmerston North City Council's approach meant that it did not deliver a credible plan for funding its activities and planned projects (in particular from year 4 of the long-term plan) to its community. The Council needed to consider other options, such as reducing levels of service, removing or deferring planned projects, and increasing rates further to keep debt amounts within its own policy parameters. The Council was aware and considered these matters but did not address them in its long-term plan because of the uncertainty about the proposed three waters reforms.

Emphasis of matter paragraphs relating to funding and financing assumptions

2.89

We included 22 emphasis of matter paragraphs related to funding and financing assumptions (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Reasons for emphasis of matter paragraphs about funding and financing assumptions

| Reasons for emphasis of matter paragraphs | Number |

|---|---|

| Uncertain external funding | 11 |

| Uncertain cost savings | 2 |

| Unbalanced budget | 3 |

| Breach of debt limits | 2 |

| Other | 4 |

| Total | 22 |

Uncertain external funding

2.90

Eleven of the emphasis of matter paragraphs related to uncertainties over whether the councils would receive planned central government or other external funding.16 This was also the reason we issued the six qualified audit opinions (see paragraphs 2.69 to 2.80).

2.91

Based on the supporting evidence, we considered that the funding assumptions of the councils issued with emphasis of matter paragraphs were reasonable. However, these assumptions had high degrees of uncertainty (for example, the timing of the funding may not have been certain or the total amount of funding had not yet been agreed).

2.92

We used an emphasis of matter paragraph to highlight to readers the relevant uncertainty of the long-term plans.

Uncertain cost savings

2.93

We issued Hamilton City Council and Rangitīkei District Council with emphasis of matter paragraphs related to proposed cost savings. We considered that these assumptions were reasonable, but we used emphasis of matter paragraphs to highlight to readers the uncertainty associated with the planned cost savings of the long-term plans. These two councils also received emphasis of matter paragraphs on their consultation document audit reports for the same reason.

Unbalanced budget

2.94

We used emphasis of matter paragraphs to highlight that, in all years of their long-term plans, Central Hawke's Bay District Council, Kaikōura District Council, and Napier City Council did not have a balanced budget, were not meeting the balanced budget benchmark, or both.

2.95

The term "balanced budget" refers to a council's surplus or deficit in its forecast financial statements. Any years forecasting a deficit mean that a council does not have a balanced budget in those years. The "balanced budget benchmark" calculates surplus/deficit differently, as prescribed by the Local Government (Financial Reporting and Prudence) Regulations 2014.

2.96

The balanced budget benchmark is calculated as planned revenue (excluding development contributions, financial contributions, vested assets, gains on derivative financial instruments, and revaluations of property, plant, or equipment) as a proportion of planned operating expenses (excluding losses on derivative financial instruments and revaluations of property, plant, or equipment).

2.97

The balanced budget benchmark is met if planned revenue equals or is greater than planned operating expenses.

2.98

Central Hawke's Bay District Council did not have a balanced budget in years 2-10 of its long-term plan. It also did not meet the balanced budget benchmark in those years.

2.99

Kaikōura District Council did not have a balanced budget in years 4-10 of its long-term plan. It also did not meet the balanced budget benchmark in those years.

2.100

In contrast, Napier City Council did not have a balanced budget in year 3 only. However, it did not meet the balanced budget benchmark in years 1-9 of its long-term plan.17

2.101

All three councils did not meet the balanced budget benchmark because they were not fully funding depreciation on critical asset classes or they were not fully funding depreciation for a sustained period of time.

2.102

Councils are required to include an annual depreciation charge on their assets, which is shown as an expense in their long-term plan forecast financial statements. Where the council's total expenses (including depreciation) are not covered by an equivalent amount of revenue, we say that the council is not fully funding depreciation. It also means that the cost of renewals will be passed on to future ratepayers.

2.103

For example, Napier City Council disclosed that, after the 2020 asset revaluations, the total depreciation expense increased significantly, and the council did not believe it was appropriate to immediately increase rates to address the impact of this.18

2.104

In their long-term plans, the three councils clearly disclosed why they considered it financially prudent to not meet the balanced budget benchmark and how they were working towards funding depreciation for their critical assets in the future.

2.105

However, given the implications of this strategy, we considered that it was important to highlight the approach that the councils were taking.

2.106

Twenty-five other councils also did not forecast to have balanced budgets in some years of their long-term plans. However, our auditors were able to obtain reasonable explanations for this. For example, a council may not be funding depreciation because it related to assets that it does not intend to renew in the future, such as a community hall.

Breach of debt limits

2.107

We included emphasis of matter paragraphs for Ruapehu District Council and Wellington City Council because they were forecasting to breach the debt limits set in their financial strategies. However, because LGFA debt covenants were not breached in either instance, we still considered that the forecast debt was prudent.

Other

2.108

We included emphasis of matter paragraphs related to funding and financing in the audit reports of the following four councils for reasons other than those described above:

- Kaipara District Council – the Council's ability to repay the debt associated with the planned Mangawhai wastewater scheme is uncertain because it is dependent on the Council's assumptions about growth and the collection of the proposed development contributions;

- Queenstown Lakes District Council – to draw attention to the uncertainty related to the Council's proposed visitor levy to fund visitor-related infrastructure;

- South Wairarapa District Council – to highlight cost and funding uncertainties associated with the needed improvements to the Featherston wastewater treatment plant; and

- Tasman District Council – to draw attention to the uncertainty over the Waimea Community Dam construction costs.

2.109

Except for Kaipara District Council, these councils also received emphasis of matter paragraphs on their long-term plan consultation document audit reports for the same reasons.

5: New Zealand Society of Local Government Managers (2019), Dollars and sense 2021: Financial and infrastructure matters and the long-term plan, page 19.

6: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans.

7: The Local Government (Financial Reporting and Prudence) Regulations 2014 require councils to include financial prudence benchmark disclosures in long-term plans.

8: Councils purchase different goods and services than households and other organisations. Therefore, councils cannot make use of forecast price indices developed for use in New Zealand to reliably forecast the impact on inflation in their long-term plans. To provide councils with reliable forecast price indices, Taituarā engages economists to produce 10-year rolling forecasts of movements in key local government costs. Indices for individual components are combined into an overall index: the local government cost index.

9: These are Bay of Plenty, Northland, and Otago Regional Councils, and Environment Southland.

10: This analysis excludes Mackenzie District Council, which had not adopted its 2021-31 long-term plan when we collected our data.

11: The LGFA had several debt limits that applied to councils when they were preparing their 2021-31 long-term plans. The limits also differed depending on whether a council had a credit rating. Generally, the LGFA limit that has the greatest influence in constraining council debt amounts is its net debt to total revenue limit. Councils that have a credit rating greater than "A" equivalent had a net debt to total revenue limit of 300% in 2021/22. This steadily reduced to a limit of 280% that applied from 2025/26 onwards. Unrated councils or councils that have a credit rating less than "A" equivalent had a net debt to total revenue limit of 175%.

12: Office of the Auditor-General (2015), Matters arising from the 2015-25 local authority long-term plans, pages 22-23.

13: In 2015, we also considered other limits, such as interest as a percentage of operating income (used by 48: councils) and interest as a percentage of rates income (used by 30 councils), but we have not collected the equivalent information from the 2021-31 long-term plans.

14: These were Ashburton District Council, Buller District Council, and Hauraki District Council.

15: These were Hastings District Council, Kaipara District Council, and Kāpiti Coast District Council.

16: These were Auckland Council, Chatham Islands Council, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Invercargill City Council, Masterton District Council, Ōpōtiki District Council, Rotorua Lakes Council, Waikato Regional Council, Waitaki District Council, Wellington City Council, and Whakatāne District Council.

17: Napier City Council was forecasting to receive significant financial contributions, which is why it set a balanced budget in all but one year.

18: Te Kaunihera o Ahuriri Napier City Council (2021), Volume two: Our detailed budgets, strategies, and policies, page 40.