Part 6: What happened: July to December 2020

6.1

In this Part, we outline key aspects of the all-of-government response to the Covid-19 pandemic from July to December 2020 and our observations. We discuss how:

- changes were made to support a longer-term response;

- carrying out longer-term work was challenging; and

- planning for a resurgence of Covid-19 took time.

Summary of findings

6.2

The Covid-19 All-of-Government Response Group (the Covid-19 Group) was established in DPMC to help make the response more sustainable. The Group was intended to do only the work that other agencies could not do, and advance a more forward-looking work programme.

6.3

The Covid-19 Group faced many challenges as the new arrangements were put in place. These challenges included staff burnout, secondees returning to their home agencies, and increasing public complacency about Covid-19 health measures. Some of the intended improvements to the Group’s operating arrangements took time to work through, and some were delayed or not able to be prioritised.

6.4

A second rapid review of the response model reiterated the need for the Covid-19 Group to have a formal mandate and clearer accountabilities. The review also stated that the Group needed longer-term resourcing.

6.5

The Covid-19 Group made further efforts to work through these particular issues while also co-ordinating planning for another community outbreak. A governance board was set up to provide dedicated oversight of the Covid-19 response.

6.6

In December 2020, there were further changes to improve the response’s sustainability. Cabinet approved revised institutional arrangements for the Covid-19 system and committed funding for them until June 2022. It also agreed to establish an additional governance board to oversee border settings.

Changes were made to support a longer-term response

6.7

On 30 June 2020, the National Crisis Management Centre was deactivated. The Covid-19 Group created in DPMC on 1 July 2020 took over many of the Centre’s functions.55 In effect, the Covid-19 Group Leadership Team replaced the Quin.

6.8

The establishment of the Covid-19 Group was one of 50 initiatives in the Government’s July 2020 Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund package. Its purpose was to continue a co-ordinated all-of-government response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The Group was responsible for:

- providing strategy and policy advice to Cabinet;

- operational co-ordination;

- data analytics, monitoring, reporting and insights; and

- public communications.

6.9

The Covid-19 Group went about delivering these functions while adjusting its structures in line with the response’s requirements.56

6.10

The Covid-19 Group also worked to allocate ongoing response activities to appropriate agencies. For example, lead responsibility for the MIQ system was transferred to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

6.11

Cross-agency governance arrangements also continued to evolve. From August 2020, DPMC’s Chief Executive trialled various meeting formats to help find the right approach to provide consistent strategic oversight of the Covid-19 pandemic.

6.12

A Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Strategic Readiness Group was set up as a subgroup of the Public Service Leadership Team to focus on longer-term Covid-19 issues.

6.13

Shortly after the new arrangements were first implemented in July 2020, the chairperson of ODESC commissioned a follow-up to the April 2020 rapid review. He asked it to provide advice on optimal structures and processes for New Zealand to be well-placed to respond, as a first priority, to any significant increase in Covid-19 activity, and also to support ongoing recovery work.

6.14

The review’s terms of reference were subsequently updated to reflect the resurgence of Covid-19 cases in August 2020 and to make the review both real-time and future focused. The second rapid review report was finalised on 30 October 2020.57

6.15

The review team found that many improvements had been made since the first rapid review. It also identified actions to further strengthen the all-of-government response. These included establishing focused Covid-19 governance to streamline and “de-clutter the governance landscape”. At the time, there were many different officials’ groups that might or might not have been considering Covid-19 matters, or considering them in a strategic way.

6.16

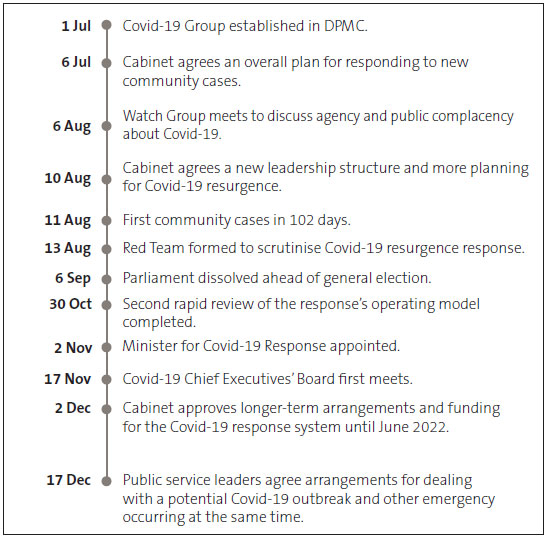

In November 2020, a dedicated Minister for Covid-19 response was appointed. A Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Board was also set up to be part of the national security system’s ongoing governance (see Figure 4). It was intended to sit alongside the Hazard Risk Board and Security and Intelligence Board.

6.17

The Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Board’s core members were the chief executives of 12 departments. They were expected to reflect the views of their sectors and wider stakeholders (including iwi, private sector, non-government organisations, and vulnerable communities). They were also expected to keep these parties appropriately informed of their discussions.

Figure 4

Composition of the Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Board, as at November 2020

Source: Adapted from Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Board draft terms of reference.

6.18

The Covid-19 Chief Executives’ Board was to provide governance of the Covid-19 response for two to three years. Its terms of reference stated that its purpose was to ensure that “the system is informed, is doing what it needs to, at the pace required, and that risks are identified and mitigated”.

6.19

The Board was also to be used for escalating complex decisions. It was to provide oversight and give assurance to Ministers, and advice to Cabinet on the system’s priorities.

Cabinet clarified and strengthened the Covid-19 response arrangements

6.20

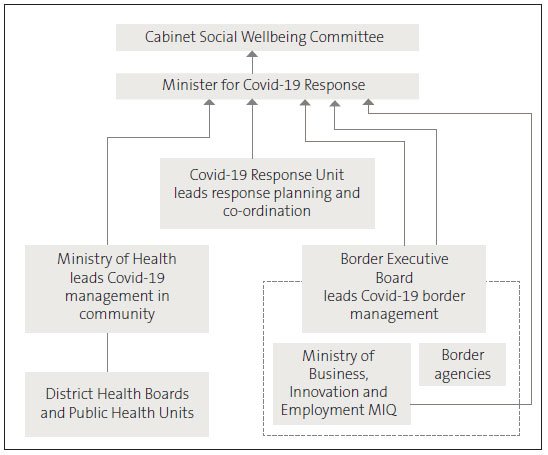

On 2 December 2020, Cabinet approved an enhanced Covid-19 response system, with clarified roles and responsibilities and funding confirmed until 30 June 2022 (see Figure 5). Cabinet agreed that one agency could not manage the response alone and that there should not be a single line of accountability for managing the full response.

Figure 5

The Covid-19 response system approved by Cabinet, as at 2 December 2020

Source: Adapted from Cabinet paper (2 December 2020), Overview of institutional and governance arrangements and funding.

6.21

Cabinet officially established the Covid-19 Group as a business unit of DPMC and gave it a mandate to provide strategic leadership and central co-ordination of the all-of-government response.58 This included responsibility for the national strategy for the response.59

6.22

Through this process, two functions were added to the Covid-19 Group: risk and assurance (including advising Ministers of emerging risks and ensuring that gaps are addressed) and system readiness and planning (including aligning agency planning).

6.23

The Covid-19 Group’s responsibilities for strategy and policy were also extended to align them with the response system as a whole. The Covid-19 Group’s other two core functions were also enhanced: insights and reporting (to include continuous improvements and sharing lessons learned throughout the system) and public communications and engagement (to include support for engaging businesses and communities).

6.24

Cabinet confirmed the Ministry of Health’s responsibilities for managing the public health response in communities. This involved surveillance, testing, contact tracing, and providing public health advice.

6.25

Cabinet also confirmed that the Ministry of Health’s Covid-19 Response System Directorate was responsible for, among other things, managing the national supply of personal protective equipment and other essential medical equipment, and for managing the health-related aspects of MIQ facilities.

6.26

Cabinet confirmed that the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment was responsible for the day-to-day running of the MIQ system.

6.27

Cabinet also approved the establishment of the Border Executive Board as an interdepartmental executive board under the Public Service Act 2020. The members of the Board were made jointly accountable to the Minister for Covid-19 Response for delivering strategic improvements to the border system, as well as other border-related outcomes that Cabinet expects.

Carrying out longer-term work was challenging

6.28

From July to December 2020, the Covid-19 Group made continued efforts to embed arrangements and ensure that they were fit for purpose. As the Group was doing this, it also looked to find new ways of working that were less reactive and more focused on the future.

6.29

There were many challenges in the Group’s operating environment. These included increasing public complacency about complying with Covid-19 health measures and the community outbreak of Covid-19 in August 2020.

6.30

Parliament adjourned in September ahead of the general election in October 2020. Pre-election conventions, such as restrictions on major government decision-making, meant that the Covid-19 Group could not carry out some of its work.

6.31

During July to December 2020, the Covid-19 Group focused on clarifying its role and remit, ensuring adequate resourcing, and progressing planning for a Covid-19 resurgence.

The Covid-19 Group made efforts to communicate its role

6.32

When the Covid-19 Group was first formed, it did not have a mandate from Cabinet to lead the system response, so it had to rely on influencing others.

6.33

This lack of formal authority put the efficiency and integration of response activities at risk. We understand that it also contributed to ongoing tensions between the Covid-19 Group and the Ministry of Health.

6.34

DPMC recognised that the complexity and fluidity of the various groupings in the response system had created challenges. We saw evidence that, from late June 2020, the Office of the All-of-Government Controller made efforts to communicate the Covid-19 Group’s proposed role. Messages about the Covid-19 Group’s role were shared at large meetings of chief executives and in individual conversations with key leaders. We saw evidence that the Group intended to develop communication and engagement plans. However, these were not always produced.60

6.35

The Covid-19 Group made increasing efforts to inform others of its objectives, structures, and functions. From July 2020, the Covid-19 Group sent weekly updates to the leaders of public service departments, a small number of Crown entities, the New Zealand Police, the New Zealand Defence Force, the Parliamentary Counsel Office, and NEMA. The distribution list extended to other agencies over time.

6.36

However, we heard that these approaches were not always effective. The Covid-19 Group recognised that sharing information sometimes depended on relationships rather than reliable processes.

6.37

In October 2020, the second rapid review found that the roles and responsibilities in the all-of-government response (particularly for the Covid-19 Group and the Ministry of Health) needed to be widely circulated in plain English. The review team found that agencies felt that the system was complicated to the point where they could not draw it.

6.38

In November 2020, the Covid-19 Group’s leadership team received advice about the need to develop a formal documented strategy and operating model setting out how the Ministry of Health, the Covid-19 Group, and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment MIQ function should work together.61

Resourcing remained a challenge

6.39

Securing adequate ongoing staffing for the all-of-government response made it difficult to progress longer-term work. Burnout and secondees returning to their home organisations contributed to vacancies.

6.40

High staff turnover created considerable burden and stress on individuals who had to carry significant workloads (see also paragraph 6.55). In August 2020, an internal Covid-19 Group document said that suboptimal staffing levels presented risks of “single points of failure” to the response.

6.41

To support the Covid-19 Group’s work facilitating workforce mobilisation, Te Kawa Mataaho created an agency deployment newsletter to communicate where the system needed resources. Te Kawa Mataaho also supported DPMC to access staff through public service talent boards.

6.42

The Covid-19 Group relied on goodwill and low cost or no cost (in-kind) support from agencies to help it work within its budget. The amount of operational funding approved to set up the Covid-19 Group in July 2020 and to run it in 2020/21 was $13.9 million.

6.43

Managing this budget was a constant matter of discussion for the Covid-19 Group Leadership Team and DPMC’s Chief Executive. Meeting minutes from September 2020 described concerns about the risk of the communications budget running out and a critical public information gap.

6.44

In a document prepared for a meeting with the Minister of Finance in October 2020, DPMC stated that it had expected to be able to access about a third of needed staff through secondments at agencies’ own costs. It had also expected to be focused on recovery by this point. These assumptions had proven incorrect.

6.45

DPMC noted that the Covid-19 Group’s staffing model and resourcing was putting its ability to provide a well-co-ordinated government response with quality advice and effective public communications at risk. DPMC sought and was given additional funding for the Group to continue critical functions in October 2020 and again in December 2020.62

6.46

In our view, careful consideration needs to be given to how acceptable it is to rely on goodwill during an extended and acute nationwide emergency. Assumptions about resourcing an evolving response need to be continually tested, and other scenarios need to be planned for and costed.

6.47

In early December 2020, 80% of the Covid-19 Group’s staff were secondees. Other agencies funded or co-funded 60% of these secondees. The Minister for Covid-19 Response (who was also the Minister for the Public Service) told Cabinet that the Group’s dependence on secondees was unsustainable and a significant risk to its operations.63

6.48

The Minister recommended that Cabinet agree to make Te Kawa Mataaho responsible for critical workforce planning and co-ordination. He told Cabinet that Te Kawa Mataaho was already under pressure to deliver public service reforms and asked that it approve funding for them to deliver this new function until June 2022.

6.49

Cabinet subsequently directed the Public Service Commissioner to help the Ministry of Health and other agencies fill urgent staffing gaps.

6.50

Te Kawa Mataaho told us that, from December 2020, it set up a team to help build Covid-19 workforce resilience and sustainability (supporting leader and workforce well-being) and provide support for agencies (facilitating connections and mobilising resources).

6.51

This is positive. In our view, it is also important to consider how wider government services can continue to be delivered during extended disruption, when public sector capacity is significantly reduced because of infection control or redirection of work efforts.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

We recommend that the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, National Emergency Management Agency, Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission, the Ministry of Health, and other relevant organisations continue to work together to:

|

Resurgence planning took time

6.52

We saw evidence that both the Ministry of Health and the all-of-government response began planning for another Covid-19 community outbreak as early as mid-May 2020. By June 2020, three separate strands of work on resurgence planning were under way in the National Crisis Management Centre.

6.53

On 6 July 2020, Cabinet considered an overall plan for responding to new community cases. The Covid-19 Group published a version of this on the Unite Against Covid-19 website on 15 July 2020. The plan outlined how the Government would respond to three scenarios.64

6.54

In our view, despite efforts to plan for resurgence, a further outbreak does not appear to have been an immediate concern for many, including public servants, when the country emerged from lockdown. As New Zealand moved down Alert Levels and entered an extended period with no new community cases, agencies began returning to their usual work.

6.55

There was widespread fatigue among staff who had been or were still working long hours on the all-of-government response. Some senior officials told us that, during the peak of the response, they had worked every day for up to 18 weeks.

6.56

Agencies were having difficulty delivering normal work programmes because they did not have enough staff. This was a particular problem for agencies with staff deployed to do border and MIQ work. These resourcing pressures affected agencies’ ability to carry out Covid-19 resurgence planning.

6.57

The Government publicly signalled a change in direction towards recovery. In June 2020, the Unite Against Covid-19 website announced a shift in focus “from keeping ourselves safe from the virus to the economic and social recovery of New Zealand”. However, this change was not sustained.

6.58

The new Unite for Recovery campaign was dropped when New Zealand recorded its first Covid-19 case acquired through the border in 24 days on 16 June 2020. The Government returned to its Unite Against Covid-19 branding and public health messages.65

6.59

Although short lived, this change in direction created some confusion. For example, we saw evidence that officials were concerned that some local authorities had already switched into recovery mode and directed their efforts away from the planning needed for resurgence.66

Officials were refocusing on resurgence planning when an outbreak struck

6.60

By early August 2020, New Zealand was approaching 100 days where no new cases of Covid-19 had been identified in the community. However, we found that some senior officials were concerned about the public’s increasing complacency.

6.61

On 6 August 2020, a large Watch Group meeting was called to discuss the need for agencies to prioritise resurgence planning. Minutes show that attendees acknowledged that New Zealand was in a privileged position but that there was a wide and incorrect assumption that we were safe from another outbreak.

6.62

Attendees were concerned about the lack of cross-agency understanding of resurgence planning and related decision-making rights, roles, and responsibilities. They agreed that the Covid-19 Group would set up a workstream to co-ordinate resurgence planning.

6.63

On 10 August 2020, Cabinet was provided with more detail on how to implement the July plan (see paragraph 6.53). Cabinet approved a new decision-making and accountability structure to deal with a resurgence of Covid-19.

6.64

A National Response Leadership Team, which included the Chief Executive of DPMC and the Deputy Chief Executive in charge of the Covid-19 Group, was to provide all-of-government advice to Cabinet or Covid-19 Ministers, and also to provide non-health advice to the Director-General of Health (to inform his use of powers under the Covid-19 Public Health Response Act).

6.65

This team was also expected to activate relevant regional response leadership groups for local responses. A National Response Group would co-ordinate planning and monitor the implementation of response activities (see Appendix 2).

6.66

However, the plan agreed by Cabinet needed further work. An update to Cabinet on the state of cross-agency resurgence planning was scheduled for the end of August 2020.

6.67

Before this could take place, the country went back into response mode. On 11 August 2020, the Ministry of Health reported four new community cases. Auckland moved to Alert Level 3, and the rest of the country moved to Alert Level 2.

Resurgence planning was strengthened after the August 2020 outbreak

6.68

During the resurgence response many issues were identified. These included unclear testing requirements for high-risk workers, poor connections between regional leadership and central government, and issues falling between the mandates of agencies.

6.69

A later review found that the national resurgence response plan had not been developed well enough before the August 2020 outbreak of Covid-19 in the community.67 The review found that those required to put it into action did not fully understand what they were meant to do.

6.70

Planning between agencies had also not been well aligned. We saw evidence that the Ministry of Health did not send its resurgence plan to the Covid-19 Group until 31 July 2020.

6.71

After the August 2020 outbreak, there were increased efforts to develop better integrated resurgence planning and improve information flows.

6.72

We were told that resurgence planning workshops were held sometime between September and October 2020. We saw evidence that DPMC and the Ministry of Health ran a workshop in November 2020 for agencies to understand the plans that DPMC and the Ministry had separately produced.

6.73

At the November workshop, DPMC outlined the intent of its current planning work. This was to provide advice to agencies on how to complete their resurgence plans and to prepare a more detailed system response plan.

6.74

The Ministry of Health told us that it worked with DPMC to seek consistency. However, some guidance about how to approach resurgence planning appeared complicated and was not always aligned.68

6.75

Further workshops were planned in 2020 but we did not see evidence that these workshops were held.

6.76

In December 2020, a combined DPMC-Ministry of Health summer resurgence planning pack was given to key people expected to be involved in a response, along with training. This was so that they would be ready for a period of higher risk during the holiday season.

6.77

Overall, the 158-page pack showed well-developed and practical planning. It outlined relevant governance and operational structures, processes and procedures, and activities to be carried out by key agencies. It also described the roles and responsibilities of other agencies and included information on district health board readiness, with varying levels of reported planning at that point.

6.78

On 13 December 2020, the Government launched a multimedia advertising campaign called Make Summer Unstoppable. This included publishing a short plan for the public that set out how the Government would respond to three scenarios of people testing positive for Covid-19.69 It also outlined what the public could do and what the Government was doing to reduce the risk of, and to be ready for, new cases.

6.79

On 17 December 2020, an ODESC meeting to discuss resurgence planning also considered what would happen if another emergency happened at the same time as a summer outbreak.

6.80

The Covid-19 Group worked with the National Security Group on how activating the national security system for a non-Covid crisis would work if resurgence response structures were also operating. This work was intended to clarify roles and responsibilities and ensure that extra staff would be available if any concurrent events happened. This was a risk that had been raised at other officials’ meetings during 2020.

6.81

We were told that further work was also carried out to review and improve national resurgence planning arrangements. This included revisions after the February 2021 outbreak and more work to prepare for Easter 2021. This was a popular time for travel, and there was increased potential for the virus to spread.

6.82

Some updates to the membership of resurgence structures were made. DPMC told us that agencies provided regular (quarterly) assurance that Covid-19 resurgence plans were in place and aligned.

6.83

In our view, the Government publishing its high-level scenario planning in July and again in December 2020 was useful. It helped the public understand what would likely happen and be required of them if an outbreak occurred. It also provided assurance that the Government was planning ahead. We strongly encourage the Government to continue to share its planning with the public.

55: The Covid-19 Group was headed by a deputy chief executive who reported to DPMC’s Chief Executive.

56: Cabinet did not officially confirm the Covid-19 Group’s role to co-ordinate and lead the response until December 2020.

57: Kitteridge, R and Valins, O (2020), Second rapid review of the Covid-19 all-of-government response, at covid19.govt.nz.

58: The Covid-19 Response Unit referred to in Cabinet papers was an extension of the Covid-19 Group. It is commonly known as the Covid-19 Group.

59: The Ministry of Health had published the elimination strategy in May 2020 and, in December 2020, worked with DPMC to complete a 125-page review on refining and improving the strategy.

60: We saw evidence that in, late June, officials identified the need for a jointly developed DPMC-Ministry of Health engagement plan. This was to promote an enduring relationship with clear roles, protocols, and communication channels. We were told that this plan was not produced but that steps were taken to improve engagement between DPMC and the Ministry. These steps included extending meeting invitations and sharing organisational charts.

61: This advice was part of a report by the Covid-19 Group’s Insights and Reporting Team, which had input from 13 agencies.

62: Actual expenditure for the Covid-19 All-of-Government Response appropriation for 2020/21 was $16.1 million, as reported in DPMC’s Annual Report. See Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2021), Annual Report: Pūrongo-ā-tau for the year ended 30 June 2021, at dpmc.govt.nz.

63: Cabinet paper (2 December 2020), Establishing a Covid-19 Response Unit, at covid19.govt.nz.

64: These scenarios were a contained cluster in a community (such as an aged residential care facility), a large cluster in a region (such as a social event at a café), and multiple clusters spread nationally (such as a large sporting event and a concert).

65: See Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Unite for the Recovery advertising, at oag.parliament.nz. Concerns had been raised with our Office about the political neutrality of the recovery advertising material. We found that the Government had taken appropriate steps to ensure that the advertising was in line with established guidelines. We found no inappropriate spending.

66: The Government was using recovery language in other contexts as it looked ahead. Support for a “post-Covid rebuild” was a key part of the Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund announced in July 2020.

67: Simpson, H and Roche, B (2020), Report of the Advisory Committee to oversee the implementation of the New Zealand Covid-19 surveillance plan and testing strategy, at covid19.govt.nz.

68: The Ministry of Health produced a Covid-19 Health and disability sector resurgence planning tool in November 2020 to help the Ministry and district health boards prepare for community cases. The tool was developed alongside DPMC’s national resurgence plan. Users were referred to the 14 other strategies, frameworks, policies, plans, and guidelines to help inform planning. The Ministry of Health’s guidance referred to the CIMS framework, but DPMC’s guidance did not.

69: These scenarios involved a border worker, someone at a campsite, and a person returning from a large music festival.