Part 2: Before Covid-19: Arrangements to prepare for a pandemic

2.1

In this Part, we describe:

- the systems that existed before Covid-19 to manage potential and actual emergencies, including a pandemic;

- the expectations to monitor risks, build capability, and test planning;

- the pre-established roles and responsibilities for responding to an emergency; and

- the other legislation and plans that were in place to support pandemic preparedness.

There were systems in place to manage potential and actual emergencies

2.2

Since 2001, the government has taken an all hazards, all risks approach to help protect the security and resilience of New Zealand and its people. This approach covers a wide range of risks, such as armed conflict, espionage, major transport accidents, infrastructure failures, and pandemics.

2.3

The approach is used to help prepare for, and respond to, events of varying complexity and severity.

2.4

DPMC leads, co-ordinates, and supports the national security system, which generally deals with major crises and operates at a strategic, cross-agency level of central government.

2.5

NEMA leads and stewards the emergency management system, which is part of the national security system. It generally deals with smaller-scale incidents, such as flooding and fires, and focuses on civil defence, operational matters, and supporting communities. Regional groups and local authorities deliver this support in partnership with lifeline utilities and other services.8

2.6

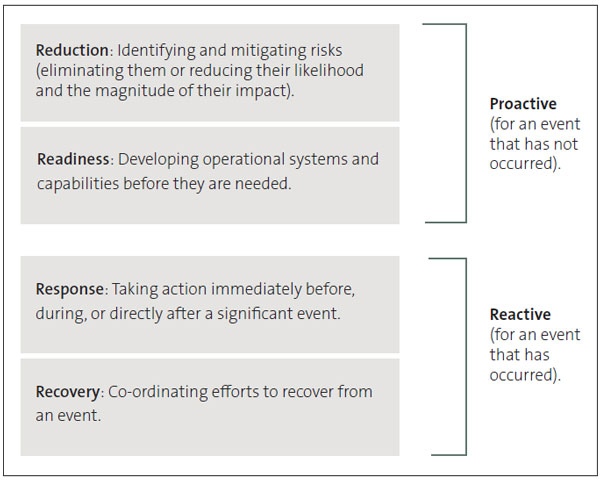

The national security system and emergency management system would usually both be activated for highly disruptive events, such as the Kaikōura earthquakes. These two systems are informed by the 4R model outlined in Figure 1.

2.7

The Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002 requires government departments (and others) to carry out civil defence emergency management functions and duties.9 Government departments must also continue functioning to the fullest extent possible during and after an emergency to meet their statutory responsibilities. This is known as business continuity.

Figure 1

The 4R model for emergency management

Source: Adapted from Royal Commission of Inquiry (2020), Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei: Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019.

2.8

Under the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan, agencies are expected to develop and maintain their own risk-based emergency management plans.10

2.9

Under the Public Service Act 2020 (and the previous State Sector Act 1988 which it replaced), departments and departmental agencies have responsibilities towards the government’s collective interests.

DPMC co-ordinates strategic risk mitigation and crisis responses

2.10

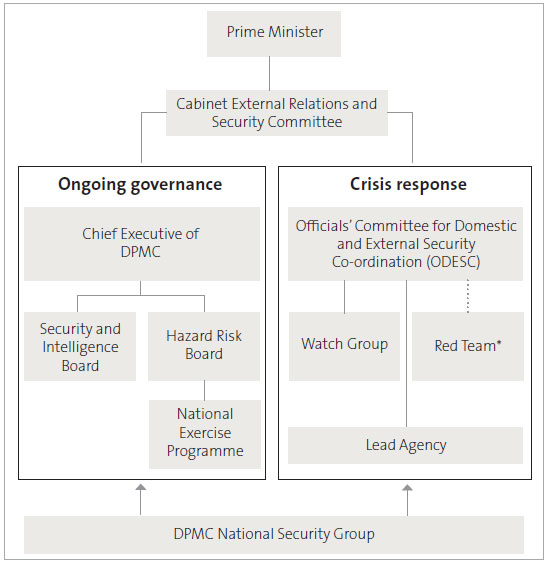

Figure 2 shows that the national security system has:

- an ongoing governance mode, with structures to lead cross-agency assessment, analysis, and treatment of risks; and

- a crisis response mode, with structures that can be activated during an emerging or actual security event.

Figure 2

The national security system

* A Red Team provides assurance to the Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination but has no formal accountability.

Source: Adapted from Royal Commission of Inquiry (2020), Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei: Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the terrorist attack on Christchurch masjidain on 15 March 2019.

2.11

In both modes, DPMC’s National Security Group leads, co-ordinates, and supports the national security system’s activities and the various agencies and officials involved in those activities.

Agencies were expected to monitor risks, build capability, and test planning

2.12

DPMC told us that it leads, oversees, and maintains a National Risk Register. When we carried out our audit, this register included 42 nationally significant risks, identified through a multi-agency process, that the two Boards in Figure 2 governed. The Security and Intelligence Board was assigned 13 threat-type risks to oversee, such as terrorism and cyber security. The Hazard Risk Board was responsible for the remaining 29 hazard-type risks, which included a pandemic.

2.13

These Boards were meant to ensure that there was appropriate oversight, alignment, and prioritisation of activities to manage these risks.

2.14

The National Exercise Programme supported the work of the Hazard Risk Board. This Programme was designed to prepare the public sector for responding to events, including pandemics, in an integrated and effective way. A planning and co-ordination team oversaw system readiness activities (known as exercises) to build capability and test planning through mock multi-agency responses to emergency scenarios.

2.15

For the risks it was assigned to govern, the Hazard Risk Board was meant to consider the reports from these exercises and any findings from debriefs and “lessons identified processes” after a response.11

2.16

Agencies were assigned responsibility for particular risks and were expected to contribute information about the risk areas that the Hazard Risk and Security and Intelligence Boards governed. In 2018, DPMC identified, and Cabinet approved, 16 National Security Intelligence Priorities to guide agencies on where they should focus their resources for monitoring and collecting information about the most important risks.

2.17

In 2019, the Government released an unclassified version of these priorities for the first time. One of these priorities was threats to biosecurity and human health.

2.18

The national security system, and relevant agencies, were expected to carry out work to reduce nationally significant risks and be ready to respond if they were realised.

There were pre-established roles and responsibilities for responding to an emergency

2.19

When an escalating crisis is identified, the crisis response mode of the national security system may be activated.12 Figure 2 shows that it is standard procedure for:

- a lead agency to run the operational response; and

- specifically formed groups of officials to provide strategic direction and oversight.

The lead agency has a range of responsibilities

2.20

The lead agency is one that has the legislative authority and/or technical expertise to manage a particular hazard.13 This model is intended to ensure that responsibilities and accountabilities for managing an emergency are clear and well understood ahead of time. The lead agency is expected to maintain enough capability and capacity to perform its role.

2.21

The lead agency is expected to advise the national security system on whether to activate the National Crisis Management Centre, which is normally located in a secure facility in the Beehive basement.

2.22

In a major emergency, the lead agency usually operates from the National Crisis Management Centre to ensure that there is a central location for:

- collecting, managing, and sharing information;

- co-ordinating and directing the response’s operations, planning, and support;

- liaising between the operational response and the national strategic response;

- supporting strategic oversight and decision-making; and

- co-ordinating the release of information publicly and liaising with media.

2.23

The lead agency is expected to fill key positions in the National Crisis Management Centre, including the overall lead Controller. If a state of national emergency is declared, NEMA works alongside the lead agency to help co-ordinate the response.14 Other agencies can supply additional personnel and support.

2.24

In carrying out its operations, the lead agency is expected to follow the Co-ordinated Incident Management System (the CIMS framework).15 This provides information about roles and responsibilities for an emergency response. It promotes the use of consistent principles, functions, protocols, and terminology so that the response can be carried out in a co-ordinated and effective way.

2.25

The CIMS framework is designed to be flexible and scalable for all hazards and risks. It allows additional structures to be set up, as necessary, under a state of national emergency or as the situation warrants.

2.26

The Ministry of Health is the lead agency for outbreaks of infectious human disease. When we carried out our audit, district health boards were the regional leads.

2.27

Under the lead agency model, the Ministry of Health was expected to co-ordinate both the national health and disability sector and the wider all-of-government response to a pandemic. This included providing guidance to agencies and setting the direction for them to lead the response for their sectors.

2.28

The Ministry of Health was also responsible for activating and running its National Health Co-ordination Centre. The Centre oversees the Ministry’s emergency response activities in the health sector, including producing and communicating official information and guidance to the health and disability sector, operational groups, and other public organisations.

Cross-agency groups provide strategic advice on crisis responses

2.29

DPMC’s Chief Executive convenes and chairs meetings of the Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC) and chooses the right mix of chief executives to attend depending on the nature of the particular crisis.

2.30

ODESC sits at the strategic level, above the management and operations of the lead agency and its statutory responsibilities. Members are expected to work as a collective to focus on the system as a whole and help ensure all-of-government co-ordination.

2.31

ODESC has limited formal powers, but it has the important role of advising the Prime Minister and the Cabinet’s External Relations and Security Committee on strategic developments, options, and priorities during a crisis. ODESC’s other responsibilities include:

- ensuring that the lead agency and organisations supporting it have the resources and capabilities they need to bring the response to an effective resolution; and

- providing strategic advice on mitigating risks beyond the lead agency’s control.

2.32

To assure ODESC that the full range of actions for a response are being considered, a Red Team can be set up to carry out a semi-independent real-time review of activities.

2.33

Watch Groups also provide advice to ODESC. They are formed to monitor a potential, developing, or actual crisis. Watch Groups comprise senior officials with relevant authority. They often meet before ODESC.

2.34

The Watch Group’s role includes ensuring that all strategic risks are being managed, identifying gaps and areas of concern, and agreeing on any further action needed.

A range of legislation and plans supported pandemic preparedness

2.35

Three main pieces of legislation provide the government with powers to manage a pandemic. They are:

- the Health Act 1956, which gives medical officers of health broad powers to manage the spread of infectious diseases;

- the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002, which allows the Minister of Civil Defence to declare a state of national emergency;16 and

- the Epidemic Preparedness Act 2006, which was created to give agencies adequate statutory power for preventing and responding to epidemics.17

New Zealand had a pandemic response strategy and plan

2.36

The public sector was expected to follow generic emergency management guidance for all hazards and risks, and more specific guidance for health emergencies, including pandemics.

2.37

Before Covid-19 emerged, the Ministry of Health’s New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan: A framework for action (the Pandemic Plan) was central to pandemic planning.18 It sets out all-of-government measures to take before, during, and after a pandemic. The following six-phase response strategy guides those measures:

- Plan for it: Plan to reduce the impacts of a pandemic and be prepared.

- Keep it out: Prevent, or delay as much as possible, the arrival of a pandemic.

- Stamp it out: Control and/or eliminate clusters of infection.

- Manage it: Reduce the pandemic’s impacts on the population.

- Manage it post-peak: Quickly progress recovery and prepare for another response.

- Recover from it: Quickly progress recovery of public health, communities, and society.

2.38

The Pandemic Plan focuses on an influenza pandemic. However, it states that the approach “could reasonably apply to other respiratory-type pandemics”.

2.39

The Pandemic Plan describes 11 workstreams. It outlines the expected roles and responsibilities of the agencies designated to lead and support each workstream, including the Ministry of Health and district health boards.

2.40

The Pandemic Plan also includes guidance on potential actions and interventions, such as border measures, testing, contact tracing, and quarantine. It identifies the legislation agencies might need to use to carry out various activities.19

Agencies were expected to develop and test their own pandemic plans

2.41

Before Covid-19 emerged, agencies were expected to develop their own pandemic plans informed by the Pandemic Plan. This was to help them lead the planning, preparedness, and response for their sector.

2.42

An Intersectoral Pandemic Group was expected to provide co-ordination and support to agencies. A Pandemic Influenza Technical Advisory Group was also meant to inform the Ministry’s planning for a pandemic response and to meet as needed. The Ministry of Health told us that, before Covid-19 emerged, its usual work included scanning for emerging threats and sharing relevant technical information as part of its weekly internal meetings.

2.43

Under the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan, agencies were expected to regularly carry out exercises and test their arrangements for responding to emergencies. They were expected to share any resulting lessons and improvements with other relevant agencies and regional groups.

2.44

Infectious human disease pandemics were identified as a hazard risk that might require co-ordination and management at a national level.

2.45 As part of the National Exercise Programme (see paragraph 2.14), the Ministry of Health led simulation-based testing of national pandemic planning in 2006/07 and 2017/18. Findings from 2006/07 included the need for regular exercises to help key staff become more familiar with roles, responsibilities, and authorities.

2.46

A core objective for the 2017/18 exercise was to familiarise senior leaders and managers with the challenges of a long-duration emergency. It was also intended to inform the Pandemic Plan’s further development. This exercise resulted in a range of recommendations. We discuss progress against these in Part 3.

8: Lifeline utilities provide essential infrastructure services to the community, such as water, transport, energy, and telecommunications.

9: Agencies are expected to assess their civil defence and emergency management capability. NEMA is expected to deliver or provide advice about training and other appropriate capability development. See National Emergency Management Agency (2015), Guide to the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan, at civildefence.govt.nz.

10: The National Plan was made under, and is set out in, the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan Order 2015. We discuss this in more detail in Part 3.

11: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2016), National Security System handbook, at dpmc.govt.nz. The Security and Intelligence Board was also responsible for carrying out these activities for the risks assigned to it.

12: Activation criteria include an issue of large scale, high intensity, or great complexity, and the need for extensive resources.

13: The lead agency model is set out in the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan (2015).

14: NEMA is also the lead agency for infrastructure failure and geological and meteorological hazards.

15: DPMC published the third edition of the CIMS framework in 2019. It was jointly developed by emergency management agencies and endorsed by ODESC. See civildefence.govt.nz.

16: The title of the Minister responsible for administering this Act was changed to the Minister for Emergency Management in November 2020.

17: This Act was introduced after the threat of a human outbreak of Avian Influenza.

18: When we wrote this report, the 2017 Pandemic Plan was still current. As we noted in our 2020 report, Ministry of Health: Management of personal protective equipment in response to Covid-19, the Pandemic Plan had not been substantively updated since 2010. It was first published in 2002, then updated in 2006. See health.govt.nz.

19: Other potentially relevant legislation includes the Health (Quarantine) Regulations 1983, the Biosecurity Act 1993, and the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015.