Part 5: What happened: March to June 2020

5.1

In this Part, we outline key aspects of the all-of-government response from March to June 2020 and our observations. We discuss how:

- officials activated the National Crisis Management Centre and developed measures specific to Covid-19;

- the new arrangements posed challenges; and

- an early review recommended more sustainable ways of working.

Summary of findings

5.2

In March 2020, officials actively looked to fill gaps in pandemic readiness and to test the arrangements for the response. Legislation was quickly created or amended. Officials moved to new ways of working.

5.3

DPMC developed and led a bespoke response structure that combined elements of pre-existing emergency planning with a new approach. This shifted the Ministry of Health away from its expected lead agency role of co-ordinating the all-of-government response to focus on leading the health system response.

5.4

This bespoke structure was seen as effective and necessary for strengthening the overall response. However, it also created confusion about roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities and led to some effort being duplicated.

5.5

When ODESC stopped meeting from April 2020, this was a significant departure from standard governance arrangements. We were told that other mechanisms were used to provide strategic oversight. However, we concluded that in practice, this was not always the case.

5.6

It quickly became clear that there needed to be a longer-term and more sustainable response to the Covid-19 pandemic. A rapid review of the response model was commissioned, and steps were taken to transition to new arrangements. These were to come into effect from July 2020.

Officials activated the National Crisis Management Centre and developed measures specific to Covid-19

5.7

On 6 March 2020, the chairperson of ODESC directed NEMA to activate the National Crisis Management Centre and to base it at the Ministry of Health instead of the usual Beehive basement. The National Crisis Management Centre was still expected to follow the CIMS framework.

5.8

On 11 March 2020, the chairperson of ODESC advised Ministers that he was taking additional steps to strengthen the response’s co-ordination. He told Ministers that he had appointed an All-of-Government Controller to liaise between the national security system and the operational response led by the National Crisis Management Centre.

5.9

The All-of-Government Controller was a new role created to oversee the all-of-government response. It included health as one of many workstreams.

5.10

From this point on, the Ministry of Health focused on leading the health system response. This included co-ordinating the health and disability sector’s response and providing advice and information to Ministers and the public.

5.11

From early March 2020, DPMC’s National Security Group organised a series of simulation exercises to test response arrangements under various scenarios (including worst case outbreaks) to help identify gaps in planning. Further Covid-19 modelling work was also done. It showed that the health system would not cope if Covid-19 spread in the community.

5.12

In mid-March 2020, the Prime Minister announced that the response would shift from “flattening the curve” (managing but tolerating the virus in the community) to “going hard and early” (taking more aggressive measures to prevent Covid-19 from spreading).

5.13

In early April 2020, the Ministry of Health developed a working paper titled Aotearoa/New Zealand’s Covid-19 elimination strategy: An overview. In early May 2020, the strategy was confirmed and published on the Ministry of Health website.

5.14

Many groups from throughout the public sector were convened to assess the impact of the unfolding Covid-19 situation on particular sectors and provide advice. These groups were generally made up of officials and subject-matter experts. They sometimes also included or engaged with industry stakeholders.

5.15

Groups of Ministers were quickly established to consider advice on Covid-19. On 2 March 2020, the Prime Minister advised Cabinet that an Ad Hoc Cabinet Committee on the Covid-19 Response would be set up.

5.16

By 19 March 2020, a Covid-19 Ministerial Group had replaced this Committee. Its role was to co-ordinate and direct the Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and it had the authority to make urgent decisions (see Appendix 2). Officials provided advice directly to this Ministerial Group and attended its meetings most days.

5.17

On 21 March 2020, the Prime Minister announced a four-stage Covid-19 Alert Level framework.45 When a state of national emergency was declared on 25 March 2020, the country went into lockdown. This required everyone except essential workers to stay home for an initial four-week period.

5.18

Before adjourning on 25 March 2020, Parliament agreed to give the Government authority to spend money, if necessary, outside its approved budget for 2019/20. An Epidemic Response Committee was also set up to scrutinise the Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some changes to legislation were needed to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic

5.19

The first simulation exercise in March 2020 highlighted that proactive use of powers under the Health Act 1956 would be crucial to help prevent the spread of Covid-19. An omnibus Bill, passed on 25 March 2020, made amendments to several Acts to put in place the necessary arrangements to respond effectively to Covid-19.46

5.20

In accordance with the Epidemic Preparedness Act 2006, once the Prime Minister had issued an epidemic notice, the use of other special powers was activated (for example, judges being permitted to modify rules of court as they saw necessary). Certain provisions were also activated under other Acts.47

5.21

On 13 May 2020, the Covid-19 Public Health Response Act 2020 came into law. This was one day after it was introduced as a Bill. Its stated purpose was to support a public health response that:

- prevents, and limits the risk of, the outbreak or spread of Covid-19;

- avoids, mitigates, or remedies the actual or potential adverse effects of the Covid-19 outbreak;

- is co-ordinated, orderly, and proportionate; and

- has enforceable measures in addition to the relevant voluntary measures, and public health and other guidance that also support that response.

5.22

The Covid-19 Public Health Response Act empowered the Director-General of Health and the Minister of Health to make orders to achieve these objectives. This included requiring people to physically distance from others and refrain from going to specified places, carrying out specified activities, and associating with specified people.

5.23

When New Zealand moved to Alert Level 1 on 8 June 2020, the extraordinary powers granted by the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act could no longer be used. This was because the country had finished a national transition period (after the end of the state of national emergency on 13 May 2020).

5.24

The Government was advised that the Covid-19 Public Health Response Act would provide sufficient powers from this point. This Act was to be valid for up to two years. Further amendments were made to the Act as the response evolved.48

5.25

The unprecedented and wide-reaching nature of the Covid-19 pandemic meant that significant and rapid work was needed to assess legislative provisions and special powers that are not normally activated. We heard that agencies did not always understand their statutory powers to act in the Covid-19 context and made many urgent requests to the Crown Law Office for legal advice.

5.26

In August 2020, a judicial review ruled that the first nine days of the Alert Level 4 lockdown (from 26 March to 3 April 2020) had been justified but unlawful. Although an order could have been issued to lawfully enforce the lockdown at the time, this was not done. The court judgment acknowledged that the unlawfulness had since been remedied.49

5.27

We saw evidence of efforts over time to improve cross-agency management and oversight of legal matters. For example, we were told that a Legal Steering Group was an effective way of keeping track of legal and regulatory work, including orders and potential amendments. This group included members from the Crown Law Office, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Justice. It was chaired by a representative of the Parliamentary Counsel Office.

5.28

Parliament’s Regulations Review Committee, chaired by an opposition member, provided scrutiny over the proper use of law-making powers in 2020. We saw evidence that its work led to improvements in some Covid-related orders.

5.29

To prepare for future emergency and crisis responses, work should be done to review statutory authorities and make sure they are clear and appropriate. The Ministry of Health told us that clarifying the specific role of the Director-General of Health in future governance arrangements and the statutory powers that are available to Ministry staff will enhance pandemic responses.

5.30

Public servants also need to better understand the legal frameworks, powers, and responsibilities for managing emergencies (see recommendation 2).

Leadership and governance structures departed from convention

5.31

The all-of-government response structure evolved further in the weeks leading up to the Alert Level 4 lockdown and its first days of implementation.

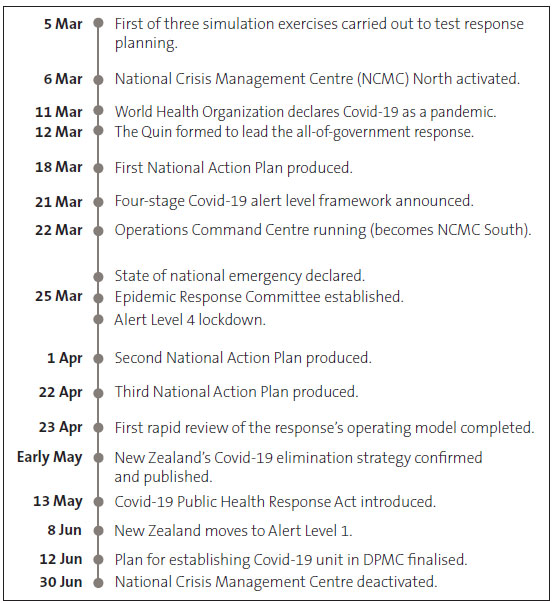

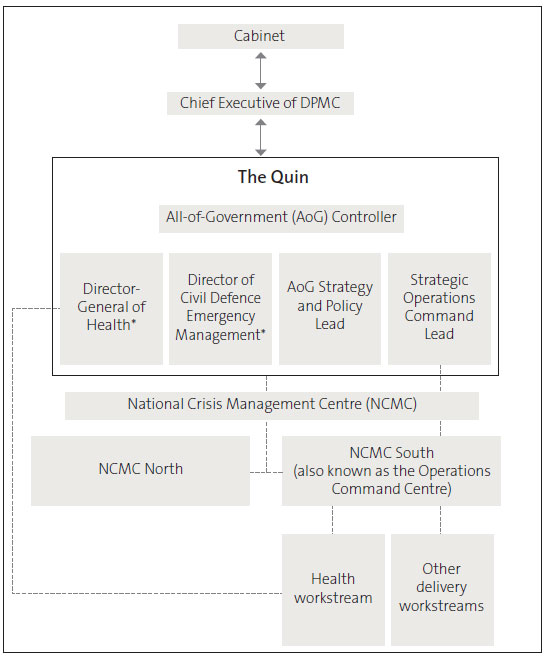

Figure 3

The all-of-government response structure for the Covid-19 pandemic, as at 1 April 2020

* These roles have statutory powers.

Source: Adapted from National Crisis Management Centre (1 April 2020), National Action Plan 2.0.

5.32

The Quin (see Figure 3) was a new leadership structure. It brought together senior officials with the statutory powers and functions to respond to a pandemic both as a public health incident (a notifiable infectious disease) and a national emergency. These officials were the Director-General of Health and the Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management respectively.

5.33

Pre-Covid pandemic guidance did not mention the need for these office holders to work in partnership. However, DPMC’s Chief Executive considered it critical that these powers be aligned. The structure also brought together newly formed strategy and operations leadership roles.

5.34

Minutes show the Quin met as a group almost daily to discuss priorities and raise emerging issues and risks with the all-of-government response. Topics ranged from the scale of testing and contact tracing to public compliance, migrant worker matters, and whether border settings were adequate.

5.35

From March to June 2020, the All-of-Government Controller officially led the all-of-government response through the National Crisis Management Centre. This was split between two locations, known as NCMC North and NCMC South.

5.36

NCMC North was based in the Ministry of Health’s national office. It included all-of-government functions for planning, communications, strategy, and policy. The Ministry also had equivalent functions focused on the Covid-19 response. This meant that NCMC North and the Ministry needed to align their activities.

5.37

NCMC South, also known as the Operations Command Centre, was based in a different part of the city from NCMC North. The New Zealand Police initially led the Operations Command Centre, but by 1 April 2020 it was incorporated into the all-of-government response structure (see Figure 3).

5.38

The Operations Command Centre was responsible for leading the operational response. This included overseeing and providing direction to cross-agency activities.

5.39

The Operations Command Centre had up to 28 workstreams. Some were set up in line with Pandemic Plan guidance, and others were created from scratch. Workstreams changed depending on what was needed.

5.40

Activities carried out through the Operations Command Centre included securing personal protective equipment and safe transportation for essential workers, setting up the MIQ system, and overseeing the health workstream’s testing and contact tracing.

5.41

A lot of people were needed for the National Crisis Management Centre’s functions. Much of this workforce was seconded from throughout the public sector. DPMC stated that, in the early weeks and months, more than 600 personnel were directly involved with the all-of-government response.50

5.42

Te Kawa Mataaho told us that, to support this, it arranged regular meetings of human resource leaders throughout the public sector to understand emerging issues and ensure a co-ordinated response. During the peak of the first Covid-19 outbreak, these meetings took place daily.

5.43

Minutes show that, by late March 2020, ODESC had expanded to 40 agencies and was sharing information and updates rather than focusing on cross-agency co-ordination and priority setting.

5.44

From early April 2020, the Chairperson of ODESC stopped convening these meetings. We were told that other mechanisms for bringing chief executives together were used in place of ODESC. This included the Public Service Leadership Team (a group of chief executives that normally meets fortnightly, chaired by DPMC’s Chief Executive).

5.45

During our interviews, we were told that the Quin performed the role of a governance board, although not everyone shared this view. Meeting minutes showed that the Quin spent much of its time in a reactive mode, managing immediate operational issues.

5.46

A Watch Group was called on 29 June 2020 to discuss an urgent review of the MIQ model. However, these meetings were not regular. The minutes recorded that “while the Watch Group was helpful for insights, it does not replace the all-of-government structure”.

5.47

ODESC did meet occasionally to discuss specific concerns in the second half of 2020. We discuss this further in Part 6.

The new arrangements posed challenges

5.48

Many people told us that the CIMS framework and lead agency models are good for responding to “short, sharp events” such as fires and floods but that they were not right for the Covid-19 pandemic.

5.49

This is because the Covid-19 pandemic has broad-reaching impacts and a long duration. Complex strategic planning and policy development are needed to respond to these. This appeared to us to be a key factor in the decision to establish the bespoke arrangements.

5.50

Most of those we spoke with said that the changes made to manage the Covid-19 pandemic were necessary and effective. People were committed to doing what needed to be done.

5.51

However, deviating from pre-existing arrangements also created challenges. Many of those related to communication and consultation (both within the all-of-government response structure and between agencies) and public servants’ ability to adapt to different and often ambiguous ways of working.

5.52

New response arrangements needed to be set up quickly under pressure and uncertainty. Several plans, strategies, and structures were drafted and revised in quick succession during this rapidly evolving period. However, it was not clear to us how well these updates and the implications of the changes for day-to-day operations were communicated to relevant parties.

5.53

The Director-General of Health remained a core part of executive direction and decision-making under the new arrangements. Both he and the Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management told us that they worked well together.

5.54

However, we heard that some saw the establishment of NCMC North to run the all-of-government response in the Ministry of Health as a takeover. This perception was exacerbated by it being primarily staffed by people from outside the Ministry.

5.55

This strained working relationships in already tense circumstances. We heard that, although NCMC North and the Ministry of Health were in the same building, their activities were not always well-integrated.

5.56

We heard that there were frustrations on both sides. The Ministry of Health faced large volumes of requests from the National Crisis Management Centre that often conflicted with other priorities that it needed to manage (including its own work to provide advice to Ministers).

5.57

We were told that adopting untested arrangements meant that decision-making rights and lines of accountability were not always clear. Assigning of tasks was not always well co-ordinated or suited to people’s areas of expertise. People we spoke to said that this caused tension, created confusion, and led to work being duplicated.

5.58

Many people involved in the all-of-government response saw the need for a single source of truth and for better information management, including to control the commissioning of work and ensure appropriate sign-out processes. NEMA told us that, from its perspective, it was common (and frustrating) for multiple requests to be made for the same information from different parts of the response structure.

5.59

The bespoke response structure shown in Figure 3 was rolled out quickly, and then adjusted many times. There were initial issues with misunderstood and missing mandates.

5.60

We were told that creating a role called All-of-Government Controller was problematic because it was sometimes confused with the National Controller – a different role that has specific statutory powers.51 People reported that this caused misunderstandings, particularly for those from the emergency management sector.

5.61

Another example was that the Strategic Operations Command Lead had no formal authority to direct agencies. To resolve this, the Prime Minister wrote to all public service leaders asking them to urgently prioritise any lawful requests from the Command Lead, along with their own statutory powers.

Governance arrangements were not always clear

5.62

A lack of formal operating procedures for the Quin likely contributed to the confusion. We understand that the Quin’s official standing was not well-communicated to the public sector.

5.63

The Quin was formed quickly. We heard mixed views about what the Quin was and what it did. The Quin had no terms of reference or formalised protocols. Decision-making was centralised to this small number of individuals. We heard that not everyone was present for all discussions, although we understand this was necessary to an extent due to competing demands on their time.

5.64

A review in April 2020 (see paragraphs 5.82-5.85) found that the Quin lacked “proper” administrative support for setting agendas, communicating decisions, and commissioning tasks. We saw evidence that its meeting records had improved by June 2020. We were told that minutes were circulated, but we did not see evidence that actions were consistently recorded or reviewed.

5.65

Other decisions to move away from expected ways of operating or to introduce new ones were not always clearly communicated to agencies.

5.66

For example, we were told that some senior officials felt that, from as early as April 2020, no body with formal governance accountabilities was consistently dedicated to looking at strategic, longer-term cross-agency issues related to the Covid-19 pandemic.52

5.67

The minutes from the first Hazard Risk Board meeting for the year (in June 2020) show that some board members were unclear on why there was a shift away from the “tried and tested” ODESC system.

5.68

Some expressed concern that it was “premature” and “jeopardised [the] visibility” of elements of the response. Some also felt that it was important to be transparent about why and how this had happened and to assess its impacts for future reference.

5.69

The chairperson of ODESC told us that he regularly checked with the Public Service Leadership Team about his decision to move away from using ODESC. He told us that it made sense to not have extra meetings during an intensely demanding and logistically difficult period when chief executives were often meeting each other and Ministers to discuss specific issues.

National Crisis Management Centre arrangements were challenging

5.70

Many people told us that having NCMC North and the Operations Command Centre in different locations was problematic. We understand that having two locations was necessary to accommodate the amount of people involved in the response and manage health and safety requirements, such as allowing physical distancing.

5.71

However, we heard that people were frustrated about poor co-ordination and alignment between NCMC North and the Operations Command Centre. We heard that communication and consultation were problematic and that roles were sometimes unclear.

5.72

We also heard that the Operations Command Centre, which included staff from the New Zealand Police and the defence and intelligence sectors, had a different style of operating than NCMC North. We understand that the separate locations meant that it was hard to unify the different organisational cultures.

5.73

Some people who joined the National Crisis Management Centre, such as staff from NEMA and the Emergency Management Assistance Team, were trained in emergency management practices. However, others were not familiar with these practices, and this sometimes caused problems.

5.74

Standardised emergency response protocols were not consistently applied. For example, NCMC North used certain reporting processes that the Operations Command Centre did not follow.

5.75

We were told that both sites produced daily reports for decision-makers at different times and in different formats and that this led to rework. Ministers were not always satisfied with how and when information was provided, and we heard that it took time to resolve the issue.

5.76

From March to May 2020, 273 staff from 45 agencies were working in NCMC North. Records show that these included 46 people from NEMA and two people from the Ministry of Health.

5.77

Excluding NEMA, only 13% of staff in NCMC North were trained in the CIMS framework.53 NEMA told us that this low percentage reflects a wider system issue that needs to be addressed.

5.78

When the National Crisis Management Centre was activated, finding extra staff quickly was challenging. We heard that senior officials found it time consuming and stressful to recruit people into the all-of-government response.

5.79

Some people we interviewed felt that Te Kawa Mataaho had a low profile during this early period of the response. Senior officials were advised in February 2020 to contact the chairperson of ODESC if they had any specific resource and supply/demand issues.

5.80

Over time, Te Kawa Mataaho provided additional assistance to support resourcing. For example, Te Kawa Mataaho worked with public service union representatives to produce Covid-19 workforce mobility guidance for state services agencies (2020).

5.81

This guidance set out principles for temporary and permanent redeployments and the broad roles and responsibilities of home and host agencies. We discuss further efforts to resource the response in Parts 6 and 8.

An early review recommended more sustainable ways of operating

5.82

The bespoke response arrangements described in paragraphs 5.31-5.47 were considered temporary. After those arrangements had been in place for about four weeks, the chairperson of ODESC commissioned a rapid review to advise on how best to structure the ongoing response.54

5.83

One of the review’s main findings was that a clear mandate was needed from Cabinet to set the scope of operations and to clarify the authority and decision-making rights of the newly created and evolving all-of-government response function.

5.84

The review team considered that DPMC was a natural home for a longer-term all-of-government response unit. This is because DPMC’s role involves leading the national security system and advising the Prime Minister.

5.85

Embedding the response structure in DPMC also meant that it could access standard corporate services that the all-of-government response needed (human resources, finance, and information technology). More conventional ways of operating were also needed to provide clarity about roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities.

5.86

Work to implement these recommendations started in May 2020.

45: This set out the public health and social measures required of communities and businesses. The restrictions were intended to be proportionate to the level of Covid-19 containment.

46: These Acts included the Education Act 1989, the Local Government Act 2002, and the Residential Tenancies Act 1986.

47: These other Acts included the Corrections Act 2004, the Electoral Act 1993, the Immigration Act 2009, and the Social Security Act 2018.

48: Amendments included provisions for the Government to recover MIQ costs from users (August 2020) and for the Minister for Covid-19 Response to make orders after consulting the Minister of Health as well as the Prime Minister and the Minister of Justice (December 2020). Before this new Ministerial portfolio was created, it was the Minister of Health who made orders for the Covid-19 response (after consulting the Prime Minister and the Minister of Justice).

49: An order under the Health Act 1956 was made after the first nine days, so the remainder of the first lockdown was prescribed by law.

50: See Governance and Administration Committee (2021), 2019/20 Annual review of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, at parliament.nz.

51: The Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management exercised legislated National Controller powers during the peak of the Covid-19 response in 2020 (25 March to 30 June).

52: The second rapid review in October 2020 also highlighted this issue.

53: This information came from an NCMC survey. Note, however, that the response rate to this question was only 30% so results should be treated with some caution.

54: Roche, B, Kitteridge, R, and Gawn, D (2020), Rapid review of initial operating model and organisational arrangements for the national response to Covid-19, at covid19.govt.nz.