Part 4: What happened: January to February 2020

4.1

In this Part, we outline key aspects of the all-of-government response in January and February 2020 and our observations. We discuss how:

- officials acted early to respond to Covid-19;

- DPMC organised more help to fill gaps in the response; and

- applicable the Pandemic Plan was for responding to the emerging Covid-19 pandemic.

4.2

For the response to the Covid-19 pandemic during 2020, we expected that:

- officials would draw on pre-existing pandemic planning and adapt it as necessary;

- the all-of-government response would be well co-ordinated and adequately resourced; and

- robust processes would be used to identify and address high-level risks and weaknesses in the overall response.

Summary of findings

4.3

As Covid-19 emerged, DPMC and the Ministry of Health performed their expected roles in monitoring the situation and carrying out initial preparedness and response activities.

4.4

During February 2020, concerns about weaknesses in pre-existing arrangements and shortcomings in the wider system for dealing with the complexities of Covid-19 were raised at officials’ meetings. It became clear that the Ministry of Health lacked enough capability and capacity for leading and co-ordinating a full all-of-government response.

4.5

Steps were taken to strengthen the all-of-government response, including bringing in more people to help the Ministry of Health with co-ordination and planning.

Officials acted early to respond to the new virus

4.6

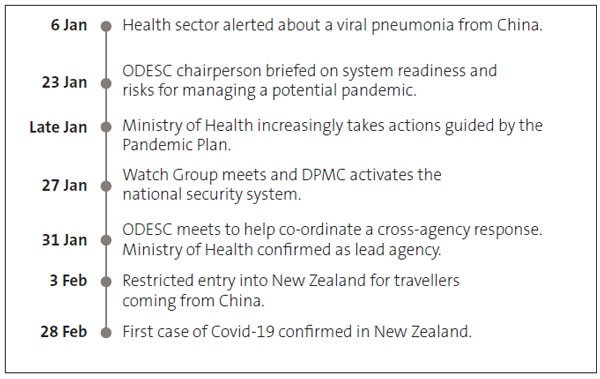

On 5 January 2020, the World Health Organization alerted member states to a viral pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China. The Ministry of Health notified the health sector the next day.

4.7

The Ministry of Health continued to monitor and respond to the situation, including engaging with its Australian counterparts and the World Health Organization. The national security system also received information on the virus from diplomatic reporting, Five Eyes intelligence partners, and unclassified sources.

4.8

By the last week of January 2020, the Ministry of Health had taken a range of actions that were guided by the Pandemic Plan. These included:

- producing daily situation reports;

- establishing an incident management team;

- convening the Intersectoral Pandemic Group and a Border Working Group;

- setting up a public health response at the border;

- directing public health units to initiate plans for contact tracing;42 and

- activating its National Health Co-ordination Centre.

4.9

Ministry of Health officials also provided advice that Cabinet should approve adding the novel coronavirus to the schedule of notifiable infectious diseases under the Health Act 1956.

4.10

DPMC’s Chief Executive formally activated the national security system on 27 January 2020. A dedicated Watch Group met on the same day, and ODESC was convened four days later.

4.11

The Watch Group and ODESC met more frequently as the virus’s threat increased. We saw evidence that ODESC was carrying out its expected functions in preparing to co-ordinate an all-of-government response. This included ensuring that the Ministry of Health, as the lead agency, had enough resources.

4.12

ODESC was also looking to improve the consistency of information, clarify the roles and responsibilities of individual agencies in the all-of-government response, align efforts, and co-ordinate advice to Ministers.

4.13

On 29 January 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade activated its own Emergency Co-ordination Centre to deal with consular and other international liaison matters. It also produced daily situation reports.

4.14

The New Zealand Police used their National Command and Co-ordination Centre to support the response. From early February 2020, they hosted an inter-agency planning and logistics function to help evacuate New Zealanders from Wuhan. The Police also hosted an inter-agency communications co-ordination group to help the Ministry of Health develop risk-based messaging.

4.15

Other agencies offered personnel to support the all-of-government response. This included providing the Ministry of Health’s National Health Co-ordination Centre with liaison officers.

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet organised more help to fill gaps in the response

4.16

Although initial response activities appeared to be carried out efficiently, we saw evidence that individual agencies were not properly prepared for a pandemic.

4.17

A briefing from the National Security Group said that the Hazard Risk Board had identified a pandemic as a “top risk” to New Zealand. The briefing also identified key risks to managing a potential Covid-19 outbreak. These included outdated business continuity plans and many public servants being untrained and unfamiliar with the Pandemic Plan and their agencies’ particular responsibilities.

4.18

There were increasing concerns at ODESC meetings during February 2020 about the Ministry of Health’s capability and capacity to lead an all-of-government response. Many throughout the public service saw the Ministry as a relatively small agency with policy, strategy, and monitoring as its core functions.

4.19

The Ministry of Health had limited direct experience in operations and service delivery. These were the domains of district health boards and their frontline staff. Some people we interviewed felt that the Ministry’s focus on public health and the health sector meant that it was not suited to also fully oversee the response’s broader social, cultural, and economic issues and impacts.43

4.20

The chairperson of ODESC raised particular concerns about a gap in the strategic co-ordination of the all-of-government response and the adequacy of public communications. He also saw the need for a stronger operational response at the centre of government.

4.21

The chairperson of ODESC brought in experienced public servants to strengthen the system-wide strategy and policy response and to ensure that agencies’ response activities were integrated. He also asked agencies to urgently provide more staff to the Ministry of Health to reduce its resourcing pressures.

4.22

Agencies made efforts to fill particular areas of capability that were needed, including policy and planning and staff trained in the CIMS framework. However, officials also acknowledged that people would have to work in new areas of responsibility, and we heard that inefficiencies sometimes arose when people without emergency planning experience were involved in developing arrangements for the response.

The Pandemic Plan had limited applicability

4.23

We heard mixed views about the Pandemic Plan’s applicability to guide the response. For some people, it provided a good start. We saw early public health advice to ODESC that said that the Pandemic Plan was a “sound framework" but that it would need adapting to respond to a coronavirus rather than an influenza.44

4.24

The Government’s communication approach to the response reflected the language from the strategic phases of the Pandemic Plan (see paragraph 2.37). When New Zealand’s first case of Covid-19 was confirmed on 28 February 2020, ODESC noted that the response needed to prepare for the Pandemic Plan’s Manage it phase, while still trying to Keep it out and Stamp it out.

4.25

However, we heard that communication about the Pandemic Plan and its intended use could have been better. People we interviewed were not always clear on what needed to be done or how to do it.

4.26

Many told us that they found the Pandemic Plan difficult to engage with and that it lacked guidance on how to implement it. Some told us that it had major gaps and that people in the health sector knew that it was outdated.

4.27

The chairperson of ODESC and many others we spoke to soon realised that the Pandemic Plan would not be suitable for dealing with the complexities of Covid-19.

42: When we carried out our audit, public health units delivered regional public health services. Their responsibilities included communicable disease control and responding to events involving risks to public health.

43: The Ministry of Health told us that, whether it leads an all-of-government response or not, the Director-General of Health’s central role and responsibilities would remain unchanged. These include providing a primary source of advice on what is required to balance public health and key legal considerations in a given situation. We discuss this further in Part 5.

44: A key difference between these two disease types is how they spread and the length of incubation. At this point, Covid-19 was considered a novel coronavirus. Much was still unknown about it.