Part 4: Matters we identified during our audits

4.1

In this Part, we set out matters that we identified during the 2020 school audits and make some recommendations for the Ministry.

School payroll

4.2

Because salary costs are the largest operational cost of schools, the school payroll information is a significant part of a school’s financial statements. The Ministry funded about $6 billion (2019: $5.4 billion) of salary and related costs to employees of schools for the 2020 school payroll year. Education Payroll Limited (EPL) administers the school payroll on behalf of the Ministry.

4.3

After Novopay was introduced in 2012, the additional payroll reports schools needed to complete their financial statements initially contributed to delays in the school audits. The school payroll audit process – which includes distributing payroll reports to schools and their auditors, and the appointed auditor of the Ministry carrying out testing of the payroll centrally – has improved in recent years. However, there was a delay to one of the key payroll reports for the 2020 school audits, and additional information had to be sent out to schools to correct some information in the report.

4.4

As Figure 1 shows, this delay in the distribution of the report to the sector did not result in a subsequent delay in auditors receiving the information they needed for audit. A record 96% of draft financial statements were provided for audit by 31 March. However, any delay and/or need for schools to make additional adjustments creates more work for schools and their auditors, who are both already under acute time pressures.

Findings from our 2020 school audits

4.5

Our auditor of the Ministry carries out extensive work on the Novopay system centrally. This includes carrying out data analytics of the payroll data to identify anomalies or unusual transactions and testing the payroll error reports that are sent to schools.

4.6

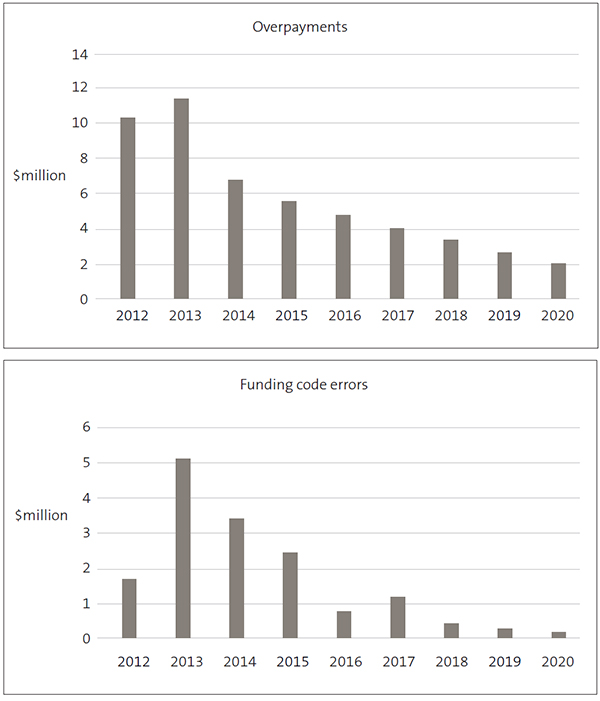

We write to the Ministry every year setting out our findings from this work. We continue to see improvements in data quality, with fewer errors each year and a reduction in the value of those errors (see Figure 17).

Figure 17

Value of payroll errors, 2012 to 2020

Note: Funding code errors are those where payroll payments have been incorrectly funded by either the board or the Ministry (through its teachers’ salary funding). These result in an amount either owed to, or owed by, the school.

Source: Education Payroll Services: Results and communications to the sector to support the audits of schools’ 31 December 2020 financial statements.

4.7

As part of their audit work at schools, our auditors follow up any anomalies that the data analytics work identified and that the Ministry cannot resolve. Some anomalies are also sent to EPL to be resolved.

4.8

The extent of the exceptions sent to schools has decreased over the years, but some matters reoccur. For the 2020 audits, we identified 1905 exceptions (2019: 2086) for 803 schools (2019: 922) that school auditors needed to follow up.

4.9

In response to a recommendation we made in 2019, the Ministry asked for feedback from schools and auditors on how the exceptions had been resolved for the 2020 audits. The Ministry also asked for feedback from EPL for those exceptions relevant to them.

4.10

Although the Ministry received feedback on all the exceptions sent to EPL and had followed-up on the exceptions provided to the Ministry, it received feedback from schools and auditors on only 16% of exceptions sent. This is most likely because the auditor shortage meant that 2020 was a challenging year for auditors, and they were focused on completing late audits when the Ministry was collecting this information.

4.11

Of the feedback from schools and auditors, most (77%) confirmed that the transaction identified as an exception was a valid payment and provided appropriate evidence of approval. Because of the low response rate and because most of the exceptions were considered valid payments, the Ministry was unable to identify any themes or opportunities for additional support or guidance.

4.12

Nevertheless, the feedback led to two recommendations for improvement. One relates to how the data analytics work is run, which should reduce the number of exceptions in future, and the other is an opportunity for EPL to provide additional guidance on a specific matter.

4.13

This exercise will be repeated for the 2021 audits, and we will support the Ministry by following up with our auditors to provide the requested feedback when they complete their audits.

School payroll changes

4.14

EPL has been progressively rolling out EdPay, an online interface for processing transactions. It was first made available for all schools to use in late 2019. Schools used a mix of EdPay and Novopay Online during 2020, while the ability to carry out tasks using EdPay has been gradually rolled out. Full replacement of Novopay Online is expected by the end of 2021.

4.15

EPL has also been working on its processes and controls, with a focus on its general management control environment and reducing the risk of payroll errors. The Ministry and EPL are also working on developing and implementing a formalised controls framework for EPL.

4.16

A school’s board is ultimately responsible for monitoring and controlling school expenditure, including payroll expenditure. It is also responsible for establishing and maintaining a system of internal controls to prevent fraud and error at the school.

4.17

Because robust controls to prevent or detect errors are not built into the payroll system, the onus is on the school to review the outputs (fortnightly payroll reports) to check that payroll transactions have been processed correctly and are both valid and accurate.

4.18

In our earlier reports, we recommended that the Ministry ensure that appropriate controls are included in EdPay. We were told that, although EdPay has some built-in validation checks that will reduce the number of errors or inappropriate transactions, no additional controls are being built into the system at this time. This means that the key controls at schools would remain the same.

4.19

Therefore, schools’ review of fortnightly payroll reports would continue to be the main control that they rely on to detect fraud and/or errors. However, we have recently been made aware that one of the main reports that schools rely on as a control is not available in the EdPay portal.

4.20

Schools will still be able to review the fortnightly Staff Usage and Expenditure report (SUE report). However, these reports are difficult to understand, which makes them difficult to review.

4.21

Some smaller schools also struggle to find someone independent of the payroll process (which means someone without access to the payroll system) with enough knowledge to review these reports. The reviewer needs to be independent, or there is a risk that the same person both processes and reviews transactions.

4.22

In our view, the guidance EPL has provided to schools does not adequately explain the control activities schools should carry out in addition to reviewing the SUE report, so the board can make sure it has appropriate controls over all its payroll transactions. We have asked the Ministry to follow up on this matter with EPL.

4.23

We also consider that more thought needs to be given to how changes to payroll processes affect the control environment at schools. We have made a specific recommendation about this that is similar to recommendations we have made in recent years.

4.24

Because the changes to the school payroll reporting occurred part way through 2021, it might affect the amount of work our auditors need to do on payroll at individual schools. As part of their planning procedures, auditors will be getting an understanding of the school payroll system, including whether controls have been operating throughout the year. We will then consider how these changes impact on the audit work we need to do at schools during the 2021 audit.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education make sure that changes to school payroll processes do not adversely affect the schools’ control environment by working collaboratively with Education Payroll Limited. This includes making sure that controls within schools help prevent fraud and error, and ensure that all transactions are approved within delegations. |

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003

4.25

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003 has arisen because clauses in the Holidays Act or employment agreements might have been incorrectly interpreted when calculating holiday entitlements. As previously reported, the Ministry has identified that there are instances of non-compliance for employees on the school payroll.

4.26

Work continues to identify and resolve non-compliance with the Holidays Act, but the Ministry has not yet been able to identify the amounts attributable to each employee and the consequent impact on individual schools.

4.27

Because school boards are the employer of all teachers, they need to recognise a potential liability for this non-compliance with the Holidays Act. However, until further detailed analysis has been completed, the potential effect on any specific individual or school and any associated liability cannot be reasonably estimated. As for previous years, all school financial statements disclosed a contingent liability for non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003.

Sensitive expenditure

4.28

This year, our auditors brought fewer matters about sensitive payments to our attention but we referred to sensitive expenditure in some schools’ audit reports, as explained in paragraphs 2.41-2.49. Several of these were for audits related to previous years. If the amounts involved are less significant or the matters relate to a school’s policies and procedures underlying its sensitive expenditure decisions, auditors will raise the matter in the schools’ management letter rather than the audit report.

4.29

Matters auditors raised in schools’ management letters this year were similar to previous years. They included:

- schools that did not have sensitive expenditure policies, including for gifts (seven schools);

- gifts to staff that were either without board approval or inconsistent with the school’s gift policy (14 schools);

- hospitality and entertainment expenses that seemed excessive

(10 schools); and - travel-related expenditure (three schools).

4.30

Most of the concerns raised about school policies and procedures for sensitive payments related to poor controls over the approval of principals’ expenses or credit card expenditure. The main matters raised were:

- principals approving their own expenses or the spending not being approved by someone more senior (40 schools);

- no approval of credit card expenditure or it not being approved by someone more senior than the person incurring the expenditure (20 schools); and

- inadequate or no documentation to support expenditure (10 schools).

4.31

As we have reported in the past, credit cards are susceptible to error and fraud or to being used for inappropriate expenditure, such as personal expenditure. This also applies to fuel cards or store cards.

4.32

Our auditors identified two schools where credit cards had been used for personal use and one school that did not have proper control over spending on fuel cards. Also, with credit cards, money is spent before any approval, which is outside the normal control procedures over expenditure for most schools.

4.33

We remind schools that they should use a “one-up” principle when approving expenses, including credit card spending. This means that the presiding member (chairperson) of the board would need to approve the principal’s expenses. It is also important that credit card users provide supporting receipts for the approver and an explanation for the spending.

4.34

We include information about using credit cards in our good practice guide on Controlling sensitive expenditure, which is available on our website. This provides guidance on principles for making decisions on sensitive expenditure, guidance on policies and procedures, and examples of types of sensitive expenditure.

4.35

We have also added some short videos about those principles and a list of other resources, including reports, articles, blog posts, and published letters, to our resources on sensitive expenditure.

Cyclical maintenance

4.36

Schools must keep the buildings that the Ministry (or, for state integrated schools, their proprietor) provides for their use in a good state of repair. They receive funding for this as part of their operational funding.

4.37

Schools need to plan and provide for future significant maintenance, such as painting the school buildings. The school financial statements include a provision to recognise the obligation for significant maintenance.

4.38

This has always been a challenging area to audit, and we have reported on this aspect of the financial statements several times in the past. Many schools do not fully understand the cyclical maintenance provision and do not always have the necessary information to be able to calculate this accurately.

4.39

This is shown by our issuing 23 audit opinions this year where we have not been able to obtain enough information about the provision. Although this is a relatively small number compared to the total number of schools, we refer to this matter in a school’s audit opinion only if the adjustment required to correct the provision could be so significant it would affect a reader’s understanding of the financial statements.

4.40

The lack of available reasonable evidence at many schools creates a lot of additional work for auditors and contributes to audits taking longer than they should.

4.41

A school’s property occupancy agreement requires the schools to prepare a 10-year property plan. This plan should include a maintenance plan that sets out how it intends to maintain its buildings for the next 10 years and the estimated cost of this.

4.42

This plan is driven by the Ministry-approved property planners condition assessment of the school buildings. If this maintenance plan is done correctly, the school can use it to calculate the cyclical maintenance provision. However, the school will need to review the plan annually to make sure that the costs and planned maintenance are still valid to be used in the calculation of the provision.

4.43

In practice, we find that schools’ 10-year property plans do not always include a maintenance plan, even though the Ministry has approved them, or the plans are out of date. After we made recommendations in our previous reports, the Ministry told us that it had updated its school property visits to include a discussion on school maintenance plans.

4.44

Our auditors have not seen an improvement in the quality of the property information at schools since this was implemented, as shown by the increase in modified audit opinions issued.

4.45

We have repeated our earlier recommendation that the Ministry needs to make sure that schools comply with property planning requirements by having up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans. As the custodian of school buildings, the Ministry needs to ensure that schools are adequately maintaining the buildings they use.

4.46

We will collect additional information from our auditors from the 2021 audits on the number of schools that do not have adequate maintenance plans. We will share this information with the Ministry to help resolve this long-standing issue.

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education make sure that schools are complying with their property planning requirements by having up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans. This includes reviewing those plans to assess whether they are reasonable and consistent with schools’ condition assessment and planned capital works. |

Budgeting

4.47

Section 87(3)(i) of the Education Act 1989 requires each school to disclose budgeted figures for the statement of its revenue and expenses, the statement of its assets and liabilities (balance sheet), and the statement of its cash flows.13 Schools need to include the budget figures from their budget approved at the beginning of the school year.

4.48

As part of their audits, our auditors check that the figures included in schools’ financial statements are from the approved budget. However, our auditors have been finding that many schools do not prepare a budget balance sheet or a budget cash-flow statement.

4.49

As well as being a legislative requirement, having a full budget, including a balance sheet and statement of cash flows, is important for good financial management. Although monitoring the revenue and expenditure of the school is important, so is managing cash flows and ensuring that schools have enough cash to meet their financial obligations when they fall due. If schools do not manage this properly, they can get into financial difficulty.

4.50

As we indicated in our report last year, we asked school auditors to tell us about schools that are not preparing a full budget. Our auditors identified 467 schools that were not preparing full budgets. We have shared this information with the Ministry so it can discuss this with the individual schools when they prepare their budgets for the next school year.

Publishing annual reports

4.51

Schools are required to publish their annual reports online.14 A school’s annual report consists of an analysis of variance,15 a list of board members, financial statements (including the statement of responsibility and audit report), and a statement of KiwiSport funding.

4.52

It is important that schools publish their annual report as soon as possible after their audit is completed. This ensures that schools comply with legislation and are accountable to their community.

4.53

As part of our audit, we check whether schools have published the previous year’s annual report. If a school does not have a website, the Ministry will publish the school’s annual report on its Education Counts website.

4.54

We have seen a continued improvement in the number of schools publishing their annual reports. At the time of this year’s audits, we found that 90%16 of schools had published their 2019 annual report on their website (2019: 82% of schools had published their 2018 annual report).

4.55

Although this improvement is encouraging, our auditors identified 231 schools that had not published their annual reports online. We encourage parents and other members of a school’s community to contact the school board if the school’s annual report has not been published online.

Future of school audits

4.56

School audits have become more complex over time because of increased financial reporting requirements and increasing professional requirements on auditors. At the same time, the number of audit firms has reduced as some smaller firms have decided to no longer carry out audits.

4.57

This has made appointing auditors for the more than 2400 school audits more challenging at each subsequent contract round.17 The resourcing pressures the profession is currently experiencing because of the closed borders have added to these difficulties.

4.58

Because of this, we have started discussions with the Ministry about the future of school audits. As well as ensuring that there is appropriate public accountability, including considering how audits can continue to be carried out in a timely manner, we are considering whether the current accountability arrangements for schools are fit for purpose. We are also interested in how well supported schools are to ensure that they are financially sustainable.

4.59

School financial statements are very detailed compared to those for many other public organisations. The Ministry is one of the main users of this information, and we understand that the Ministry uses this financial information for numerous purposes.

4.60

A small cross-sector working group carried out some work to simplify the 2021 Kiwi Park model financial statements. However, we encourage the Ministry to continue to consider whether the current level of disclosure is necessary, particularly for information that the Ministry already holds. We will discuss further opportunities to simplify the model statements when the 2022 model financial statements are developed.

4.61

In terms of improving information flows, one of our audit service providers will carry out a pilot project for a group of schools with a large provider of school financial services. This will focus on better information flows between the Ministry, the financial service provider, schools, and auditors. We hope that the initiatives developed in this pilot will benefit other schools and service providers in the future.

4.62

We are also discussing longer-term solutions. This includes what school financial reporting should look like and/or what assurance over that reporting is needed. We are in the early stages of these discussions.

4.63

A new planning and reporting framework will come into effect on 1 January 2023. The Ministry is currently establishing regulations outlining the process, content, form, and timelines for this framework.

4.64

The Ministry is also in the early stages of organisational redesign to establish Te Mahau (previously referred to as the Education Service Agency) following the review of Tomorrows’ Schools. The aim of this redesign is to work more regionally and provide more locally responsive, accessible, and integrated services to schools and the education sector.

4.65

These two significant developments provide opportunities for the Ministry to consider the accountability arrangements for schools and how they can be supported in financial matters.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education simplify the level of financial reporting required in the Kiwi Park model financial statements. This includes reconsidering information the Ministry of Education specifically requires, in addition to what is required by financial reporting standards, and whether it can obtain that information from other sources. |

Integrity in the public sector

4.66

We continue to focus on ethics and integrity in the public sector. We have already referred to the additional resources on sensitive expenditure we have put on our website (see paragraph 4.35). Another area that is important to schools is conflicts of interest.

4.67

The risk of conflicts of interest in small communities, which many schools operate in, is inherently high. There is a particular risk of conflict in the decision-making processes used to appoint new employees and contractors, and to purchase goods and services. This is because the board may have limited options in a small community.

4.68

Having a conflict of interest does not necessarily mean a person has done anything wrong. However, it is important that schools properly manage conflicts and that they do this transparently.

4.69

As we noted in paragraph 2.56, we identified five schools that had board members who did not comply with the rules in the Education and Training Act 2020 about conflicts of interest. The main provisions of the Act that school boards need to be aware of are that:

- an individual is not capable of being a trustee if they are concerned or interested in contracts with their board where the total payments in a financial year are more than $25,000 (including GST), unless the Secretary for Education approves the contract(s); and

- a permanently appointed member of board staff cannot be elected (or appointed or co-opted) to the board of trustees unless they are the elected staff representative.18

4.70

School boards are unique in that the principal (who is essentially management) is also one of those charged with governance. All boards also have a staff representative and sometimes a student representative, and integrated school boards also include representatives of their proprietor.

4.71

Boards need to properly manage decisions that they make on matters that members have an interest in. A board member should be excluded from any meeting while it discusses or decides a matter that the trustee has an interest in. However, the board member may attend the meeting to give evidence, make submissions, or answer questions.19

4.72

A good way of ensuring that there is awareness of all potential conflicts is to maintain an interests register and to have a formal process for declaring any interests at the start of board meetings.

4.73

Resources on our website include a good practice guide, Managing conflicts of interest: A guide for the public sector, and other resources, such as an interactive quiz that covers a range of scenarios where interests may conflict.

4.74

Other resources in the good practice section of our website that may be of interest to school boards are guides on:

13: Section 87(3)(i) of the Education Act remains in force because the section of the Education and Training Act 2020 for school planning and reporting does not come into effect until 1 January 2023.

14: Section 136 of the Education and Training Act 2020.

15: An analysis of variance is a statement where a school board provides an evaluation of the progress it has made in achieving the aims and targets set out in its Charter.

16: 90% of the 2273 schools that had completed their audits as at 31 October 2021.

17: Auditors are appointed for a three-year contract period. The latest period is for the 2021 to 2023 school audits.

18: Sections 9 and 10 of Schedule 23 of the Education and Training Act 2020 – previously, section 103 of the Education Act.

19: Section 15(1) to 15(4) of the Education (School Boards) Regulations 2020.