Part 2: What our audit reports said

2.1

In this Part, we set out the results of the 2020 school audits2 and the results of any audits for previous years that we have completed since we reported on the 2019 school audits.

2.2

We issued a “standard” unmodified audit report for most schools. This means that, in our opinion, those schools’ financial statements fairly reflect their transactions for the year and their financial position at the end of the year.

2.3

Our “non-standard” audit reports include either modified audit opinions or paragraphs drawing the readers’ attention to important matters. We explain these further below.

Modified audit opinions

2.4

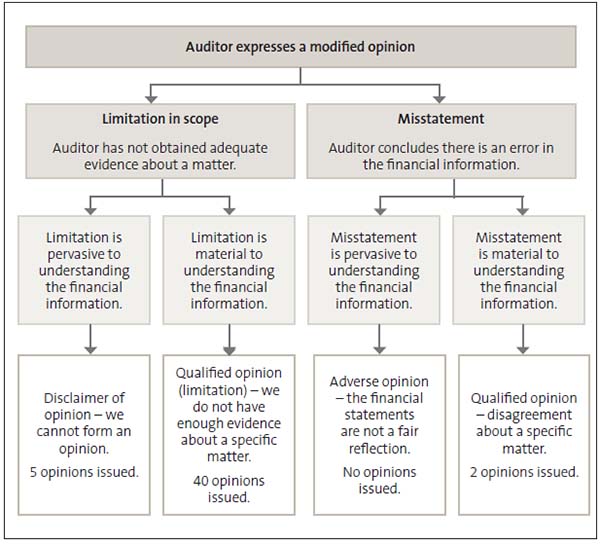

We issue modified audit opinions if we cannot get enough evidence about a matter or if we conclude that there is an error in the financial information, and if that uncertainty or error is significant enough to change a reader’s view of the financial statements.

2.5

Figure 3 explains the different types of modified audit opinions and why we issue them. It also summarises the modified audit opinions we have issued since our last report.

2.6

Of the completed audits for 2020, 24 audit reports contained a modified audit opinion. We also issued a further 23 modified opinions for previous-year audits that were outstanding since our last report.3 This is an increase on the number of modified audit opinions that we normally issue, but it remains a small percentage of all audit opinions we issue. We explain the types of modified opinions we issued below.4

Figure 3

Types of modified opinions

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

Disclaimers of opinion

2.7

We issue a disclaimer of opinion when we cannot get enough audit evidence to express an opinion. This is serious because there is a lack of public accountability – we cannot confirm that the school’s financial statements are a true reflection of its transactions and balances. We issued a disclaimer of opinion on the financial statements of two schools.

2.8

We issued a disclaimer of opinion for Al-Madinah School because we were unable to provide an opinion on its 2018 financial statements. This was because the school had limited controls over cash receipts, payments to suppliers, and the identification and disclosure of related-party transactions between the board and the proprietor, and between staff, family members, and other parties.

2.9

We issued similar disclaimers of opinion for Al-Madinah School’s 2016 and 2017 financial statements, which we have reported on previously. We also drew attention to the school failing to submit its 2018 audited financial statements to the Ministry by the statutory deadline of 31 May 2019.

2.10

We also issued the audit reports for Al-Madinah School’s 2019 and 2020 financial statements during 2021. For 2019, we were unable to give an opinion about the comparative figures reported in the financial statements because of the prior year disclaimer of opinion. However, we were able to give assurance over the 2019 and 2020 financial information the school reported. The 2020 audit was also completed by 31 May 2021, bringing the school’s audits up to date.

2.11

In December 2020, we completed the audits of Te Kura o Pakipaki for 2015 to 2018. We issued a disclaimer of opinion on all four years, consistent with the opinion on the 2014 financial statements we had previously issued.

2.12

We could not get enough evidence about bank accounts, revenue and expenditure, and some assets and liabilities of the kura. This was because there was a lack of controls over cash receipting and expenditure from a bank account under the kura’s control and a lack of supporting documents for some transactions.

2.13

We also drew attention to the kura’s financial difficulties in 2015 and 2016, and to it breaching legislation by failing to keep appropriate accounting records and meet statutory time frames.

2.14

The audits for Te Kura o Pakipaki are now up to date. Because of the disclaimer of opinion for 2018, the 2019 audit report (also issued in December 2020) referred to our not having enough audit evidence about the opening balances and comparative figures. However, we were able to give an opinion about the 2019 information.

2.15

The audit report for 2020 was issued without a disclaimer of opinion by the 31 May statutory deadline.

Disagreements

2.16

If a school has prepared its financial statements inconsistently with applicable accounting standards or we consider that the financial statements include a significant error, we issue a qualified opinion that sets out where we “disagree” with the school. We issued this type of opinion for two schools.

2.17

For the ninth year, we disagreed with William Colenso College for not preparing consolidated (or group) financial statements that included the transactions and financial position for the William Colenso College Charitable Trust.

2.18

We consider that group financial statements are required because the college “controls” the Trust for financial reporting purposes. The college disagrees with our assessment. As a result, the college is not being transparent about all its transactions and financial position to its community.

2.19

We also disagreed with Renew School not including a cyclical maintenance provision in its 2019 financial statements.5 This is a departure from the relevant financial reporting standard, which requires that a provision be recorded to estimate the cost of the school’s obligation to keep its buildings in a good state of repair. The school recognised a cyclical maintenance provision in its 2020 financial statements.

Limitations of scope

2.20

We issue “limitations of scope” qualified opinions when we cannot get enough evidence about one or more aspects of a school’s financial statements. The audit report explains which aspect of a school’s financial statements we could not corroborate. We explain the types of limitations of scope that we reported on this year.

Locally raised funds

2.21

If a school receives funds from its community, it is important that it has appropriate controls to correctly record all the money it receives. We could not get enough evidence about the amounts raised locally for the schools and kura listed in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4

Schools with “limitation of scope” opinions about locally raised funds

| 2020 audits | Previous year audits |

|---|---|

| Linkwater School | Makarika School (2018 and 2019) |

| The Taumarunui High School Community Trust | Opihi College (2019) |

| St Peter’s College Hostel Limited (2018 and 2019) | |

| St Peter’s College Foundation (2018 and 2019) | |

| St Peter’s College Hostel Trust Group (2018 and 2019) | |

| Te Kura Kaupapa o Te Puaha o Waikato School (2019) |

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

2.22

We also reported on other matters in some of the audit reports:

- We were unable to verify some expenditure transactions for Makarika School because of a lack of supporting documents.

- We could not verify the accuracy of the information included in the statement of service performance for St Peter’s College Hostel Charitable Trust Group and St Peter’s College Hostel Limited because there was insufficient supporting documentation.

- The board used a disestablishment basis when preparing the financial statements of the St Peter’s College Foundation because it is to be wound up.

2.23

We reported in earlier reports on a lack of controls over revenues for The Taumarunui High School Community Trust (2019 and 2018) and Opihi College (2018).

Cyclical maintenance

2.24

Schools are required to maintain the buildings provided by the Ministry or their proprietor (if they are an integrated school), and they receive funding for property maintenance as part of their operations grant. The school’s property occupancy agreement sets out this obligation.

2.25

Certain types of maintenance, such as painting the exterior of the school, are needed only periodically. Schools must recognise their obligation to carry out this maintenance as a provision for cyclical maintenance in their financial statements.

2.26

School boards are responsible for calculating their cyclical maintenance provision based on the best information available. For several years, we have found that some schools do not have evidence that their cyclical maintenance provision is reasonable.

2.27

This year, there has been an increase in audit opinions issued where we did not have enough evidence about the amount recorded in the financial statements for cyclical maintenance. Twenty of these opinions related to the 2020 audits, and three related to 2019. This compares to only two opinions issued last year and 15 in the previous year.

2.28

Figure 5 lists the schools that did not have enough evidence about cyclical maintenance for the 2020 and 2019 audits.

Figure 5

Schools and kura with “limitation of scope” opinions about cyclical maintenance

| 2020 audits | 2019 audits |

|---|---|

| Aranga School | Ngata Memorial College |

| Blaketown School | Te Waha o Rerekohu Combined Schools Board |

| Cobden School | Westbrook School |

| Emmanuel Christian School | |

| Granity School | |

| Greymouth Main School | |

| Howick Intermediate | |

| Kaitoke School | |

| Lynmore Primary School | |

| Nelson College | |

| Ngata Memorial College | |

| Okiwi School | |

| Saint Albans Catholic School (Christchurch) | |

| Saint Mary’s School (Blenheim) | |

| Springston School | |

| Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Otepou | |

| Te Waha o Rerekohu Combined Schools Board | |

| Waiau School | |

| Waitara Bay School | |

| Westbrook School |

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

2.29

There could be situations where a school is uncertain about whether it needs to maintain its buildings because it has significant building works planned. Because of this, the school might not be able to estimate its future obligations for cyclical maintenance. Where this is the case, we would expect the school to explain why it does not have a cyclical maintenance provision in its financial statements. As we consider this to be useful information to readers, we draw attention to these disclosures in our audit report (see paragraph 2.50). This is not a modification of the audit opinion.

2.30

We discuss cyclical maintenance in more detail in paragraphs 4.36-4.46.

Matters of importance that we draw readers’ attention to

2.31

In certain circumstances, we include comments in our audit reports to either highlight a matter referred to in a school’s financial statements or note a significant matter a school did not disclose. We do this because the information is relevant to readers’ understanding of the financial statements.

2.32

These comments are not modifications of our audit opinion. We are satisfied that the financial statements fairly reflect the schools’ transactions and financial position. Rather, we point out important information, such as a matter of public interest, a breach of legislation or disclosures in the financial statements that are important to a readers’ understanding of the financial information. This includes when we consider schools are experiencing financial difficulties, which we discuss in Part 3.

2.33

We set out details of the matters we drew attention to below.

Covid-19 wage subsidy

2.34

During our audits, we identified two schools that had claimed the Covid-19 wage subsidy despite not being eligible to receive it. Schools (as state sector organisations) were generally not permitted to claim the wage subsidy unless they had an exception from their monitoring agency (which is the Ministry for schools). The Ministry did not provide exceptions, instead it provided schools with additional funding and support throughout 2020 in response to Covid-19.

2.35

The Ministry of Social Development set criteria that organisations had to meet to be eligible to claim the wage subsidy. The organisation’s total revenue must have reduced by at least 30% compared with the same time the previous year.

2.36

Ponsonby Primary School received $49,207 under the Covid-19 wage subsidy scheme because it was unable to hold its Taste of Ponsonby event during the Level 4 lockdown. Even though its fundraising revenue had reduced, the school’s total revenue in May 2020 had not reduced by 30% compared to May 2019. Therefore, it was not eligible for the subsidy. The board repaid the wage subsidy after the end of the year.

2.37

Lindisfarne College received $123,703 under the Covid-19 wage subsidy scheme. From the information the school provided in support of its claim, we identified that the school’s total revenue did not decline by at least 30% in between the respective months in 2020 and 2019. Therefore, it was not eligible for the wage subsidy.

Potential conflicts between the school board and proprietor

2.38

For the ninth year, our audit report for Sacred Heart College (Auckland) for 2018 drew attention to the close relationship between the school, its proprietor, and the Sacred Heart Development Foundation (the foundation). The school, the foundation, and the proprietor all have board members in common, and the principal receives remuneration from the foundation. This gives rise to potential conflicts of interest.

2.39

Consistent with earlier audit reports, the 2018 audit report also notes that the school should not pay for hospitality to further relationships between the foundation and former students of the school. Although the foundation is related to the school, it is a private organisation that the school’s board does not control. It is not clear whether the school would benefit from the spending. The audit report also drew attention to the school’s failure to meet the statutory deadline.

2.40

These matters have now been resolved. The 2019 audit report for this school referred to the breach of the May 2020 deadline because it was not completed until April 2021. However, a standard audit report on the 2020 financial statements was issued because that audit was completed on time.

Sensitive expenditure

2.41

Sensitive expenditure is any spending by an organisation that could be seen to be giving private benefit to staff additional to the business benefit to the organisation. The principles that underpin decision-making about sensitive expenditure include that the expenditure should have a justifiable business purpose, and be made transparently and with proper authority.

2.42

The board of Papatoetoe North School gifted several hardware items costing $4,310 to the principal of the school as a leaving gift and paid for a farewell event costing $8,695. The board also gave farewell gifts of $1,000 each to two staff members and spent $2,200 on a function for a former teacher. Another important principle of spending on sensitive expenditure such as farewell gifts and retirement functions is that it should be moderate and conservative, and appropriate to the occasion.

2.43

We drew attention to the board of Manurewa West School not obtaining approval from the Ministry for various well-being payments, and revitalisation and refreshment grants, that it paid to the principal in 2017 and 2018. Schools need the Ministry’s approval (or concurrence) for any benefits paid to principals outside the collective agreement.

2.44

We also drew attention to the school paying for the principal and his spouse to travel to Singapore to attend the World Education Leadership Conference. Subsequently, the principal repaid his spouse’s travel costs and his daily incidental travel allowances to the school. The school’s 2019 and 2020 audits were also completed in the year, bringing its audits up to date.

2.45

It is important that spending on sensitive expenditure is transparent and open to scrutiny. Because of this, we might draw readers attention to it. We encourage schools and other public organisations to make disclosure of this type of expenditure in their financial statements, and since 2018 schools are now required to include disclosure about significant overseas travel.

2.46

As an example of this, we drew attention to the information Te Kura Māori o Nga Tapuwae included in its 2017 financial statements about a trip to Toronto to attend the World Indigenous Peoples Conference on Education and present two papers. The issuing of this audit report was significantly delayed because of auditor delay.

2.47

The financial statements explained the reasons for the travel, the total amount spent, and how this was funded. We drew attention to this information because it was a significant spend for the kura and it is good practice for schools and kura to explain the reasons for significant spending, such as this, to their communities.

2.48

Because of the delays to the 2017 audit, the subsequent audits were also delayed. The 2018 and 2019 audits for this kura are now complete.

2.49

We issued a standard unmodified opinion on the 2016 financial statements of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Kokiri following several years of modified opinions because of a lack of supporting information for expenditure under the control of the board. However, our audit report did refer to the fact that we could not verify that the $33,064 spent on fuel was incurred for the benefit of the kura.

Other matters

2.50

For five schools and kura, we drew attention to the fact that they reversed their cyclical maintenance provisions: Pongakawa School, Tauhara College, Te Kura o Matapihi, Tongariro School, and Arowhenua Māori School (for 2019). These schools could not reasonably estimate their cyclical maintenance provisions because of uncertainties over future maintenance. The uncertainties for some of these schools arise because of weathertightness issues or because they are part of the Ministry’s refurbishment and redevelopment project.

2.51

When a school closes or is due to close, its financial statements are prepared on a disestablishment basis. This is because the school is no longer a “going concern” and its assets will be distributed after it has closed.

2.52

We issued an audit report for Te Kura o Hata Maria (Pawarenga) that refers to the financial statements being prepared on a disestablishment basis because the kura closed on 28 April 2020.

2.53

The audit report of the combined board of Geraldine High School and Carew Peel Forest School drew attention to the disestablishment of the combined board on 5 July 2021. The schools established separate boards from that date.

Reporting on whether schools followed laws and regulations

2.54

As part of our annual audits of schools, we consider whether schools have complied with particular laws and regulations. We primarily look at whether they complied with financial reporting requirements, but we also consider whether they met specific obligations required of them as public sector organisations.

2.55

The Education and Training Act 2020 and the Crown Entities Act 2004 are the main Acts that influence schools’ accountability and financial management.

2.56

Usually, schools disclose breaches of the Education and Training Act and the Crown Entities Act in their financial statements, but we sometimes report on breaches in a school’s audit report. From our audits this year, we identified that:

- 27 schools (2019: 34)6 borrowed more than regulation 12 of the Crown Entities (Financial powers) Regulations 2005 allows;

- one school (2019: 2) did not use the Ministry’s payroll service to pay teachers, which section 578 of the Education and Training Act requires them to use for all teaching staff;

- one school (2019: 6) invested money in a way not allowed under section 154 of the Education and Training Act;

- five schools (2019: 7) had board members who did not comply with rules about conflicts of interest in sections 9 and 10 of Schedule 23 of the Education and Training Act;

- two schools (2019: 2) did not comply with the banking arrangements set out in section 158 of the Crown Entities Act; and

- four schools (2019: 2) breached legislation for other reasons.

2.57

Since 2016, we have found an increase in the number of breaches of the borrowing limit. This was mainly because many schools were entering into leases that are considered finance leases. Therefore, they are a form of borrowing. The number of borrowing limit breaches are beginning to reduce, from a high of 49 in 2017 to 27 this year.

2.58

This year, we did not identify any schools that lent money to staff compared to four schools for 2019. Under section 154 of the Education and Training Act, schools are not allowed to lend money to staff.

2.59

We have provided details of all the non-standard audit reports issued to schools and breaches of legislation reported as at 31 October 2021 on our website. We also provide the data as an interactive map.

2: This includes the audits of public organisations related to schools.

3: This includes four audit reports that refer to a qualification on the previous year’s figures included in the financial statements because of a qualified audit opinion in that year.

4: These audit reports are for 2020 unless noted otherwise.

5: The 2019 audit report for this school was issued on 26 October 2020 but was omitted from last year’s report on the results of the 2019 school audits, which reported on all school audits completed as at 31 October 2020.

6: The 2019 figures have been updated for audits completed since our last report.