Part 5: Planning for, managing, and evaluating public accountability

5.1

The extent and nature of the concerns raised about public accountability suggest more work, and possibly new thinking, is needed for the public accountability system to keep up with the public's expectations and the realities of a modern public sector.

5.2

Meeting this challenge will need a framework for thinking about what is important for establishing effective public accountability when implementing public policy and delivering services.

The essential elements of public accountability

5.3

As discussed in Part 2, the public sector's competence, reliability, and honesty are not only important in delivering public services but are also attributes that the public looks for in judging trustworthiness. It makes sense that a public accountability system should provide ways for the public to establish, understand, and discuss whether their expectations about these three attributes are being met. As we show below, public accountability is more than just good communication or greater transparency.

5.4

There has been a steady stream of research about how accountability is established in practice. For example, Sulu-Gambari describes accountability as a mechanism involving three elements: information, debate, and judgement.103 Bovens and others provide a framework comprising four interrelated questions: "... ‘who' is accountable to ‘whom', ‘how' and for ‘what'?"104 Bovens himself defines public accountability as:

… a relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgment, and the actor can be sanctioned.105

5.5

Ashworth and Skelcher prepared a framework for assessing local government accountability in the UK.106 The framework focuses on four elements:

- how citizens' views are taken into account;

- how a local authority gives an account;

- how citizens hold the local authority to account; and

- the options for redress.

5.6

Mees and Driessen assessed the accountability of local governance arrangements for adapting to climate change in the Netherlands.107 Their evaluation framework is based on five elements: clear responsibilities and mandates, transparency, political oversight, citizen control, and checks and sanctions.

5.7

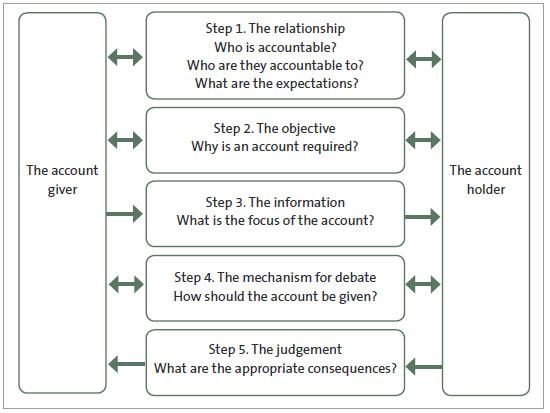

This research into how accountability is established in practice suggests five essential elements, which we set out in Figure 5. We think these elements can be used to form a five-step process for establishing or evaluating public accountability arrangements between a group or individual that is accountable (the account giver) and a group or individual they are accountable to (the account holder).

Figure 5

The five essential steps of public accountability

There are five essential steps that are necessary between the account giver and the account holder to establish public accountability – the relationship, the objective, the information, the mechanism for debate, and the judgement.

Source: Adapted from: Sulu-Gambari, W (2014), Examining public accountability and policy issues in emerging economies: A case study of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Nigeria; Bovens, M, Schillemans, T, and 't Hart, P (2008), "Does public accountability work? An assessment tool"; Bovens, M (2005), "Public accountability – A framework for the analysis and assessment of accountability arrangements in the public domain"; Ashworth, R and Skelcher, C (2005), "Meta-evaluation of the local government modernisation agenda"; and Mees, H and Driessen, P (2018), "A framework for assessing the accountability of local governance arrangements for adaptation to climate change".

5.8

The five steps should all be aligned with each other. For example, if the purpose of the accountability arrangement is to demonstrate competence (Step 1), the objective might be to encourage improved performance (Step 2). Therefore, more emphasis could be given to performance targets (Step 3), reporting (Step 4), and consequences that control any infringement (Step 5).

5.9

However, if the purpose of the accountability arrangement is to demonstrate honesty (Step 1), the objective might be about ensuring proper behaviours (Step 2), which means more emphasis could be given to information on fraud and corruption (Step 3), through mechanisms such as modelled behaviours, probity audits, inquiries, or reviews (Step 4), with consequences that control infringements but also motivate good behaviour (Step 5).

5.10

For a public accountability arrangement to be effectively established and seen to be established, each of the elements is needed, as are appropriate structures and institutions to support the elements. These include those who have an overall stewardship and leadership role and those who support and promote the proper functioning of the system.

Planning for and managing public accountability

5.11

For public accountability to be effectively established, mechanisms need to be designed and managed on an ongoing basis as an integral part of public sector activity. Thinking about public accountability as a process can help, and there might be a role for some independent assistance with, or assurance over, that process. The five process steps are discussed in more detail below.

Step 1 – Understanding the relationship: Who are the parties and what are their expectations?

5.12

The first step is about understanding who the account holder and the account giver are, the nature of their relationship, and their expectations. Understanding the nature of the relationship has implications for all other steps in this process. For example, the relationship could be with multiple parties, each with diverse cultures and customs.

5.13

Understanding each party's expectations and what attributes (competence, reliability, and honesty) should be focused on is important for determining what is needed for the other elements of the public accountability process. All three attributes should be covered to some extent.

5.14

In some instances, the nature of the relationship might mean that a formal accountability arrangement between the account holder and account giver is not needed. For example, if the relationship is built on a shared goal, the two parties could be in a position to trust each other and a more informal accountability approach might be appropriate.

Step 2 – Defining the objective: Why is an account required?

5.15

The second step is to identify and define the objectives of the accountability arrangement. The objectives of an accountability arrangement should reflect the expectations of the parties and what these mean for demonstrating the desired attributes of public trust and confidence.

5.16

Objectives can include: promoting learning, adaptability, and innovation; developing good behaviours and decision-making; improving performance; increasing responsiveness; supporting a shared understanding; ensuring proper representation and legitimacy; gaining reassurance; or offering a place for public expression.

5.17

At times, wider public sector objectives will also influence the extent of the public accountability arrangements. For example, public accountability might need to be constrained in a national security context to avoid damaging the public interest or the security of the nation.

Step 3 – The information: What is the focus of the accountability arrangement?

5.18

The third step is about identifying the focus of the accountability arrangement – that is, what it is about and what information is relevant to it. This information is what the account giver provides to the account holder.

5.19

It is important to use the right accountability information to meet the objectives and the expectations of the account holder and account giver. For example, the New Zealand public management reforms in the 1980s were primarily a response to widespread concerns about the lack of performance and responsiveness in the public sector.

5.20

Because the objectives were to improve performance and decision-making, the accountability information used focused on efficiency, effectiveness, outputs, and outcomes. Gill observes that, among other consequences, the 1980s reforms resulted in a more efficient, responsive, financially accountable, and fiscally controlled public sector.108

5.21

Where there are multiple objectives, a balanced set of accountability information is important. This might involve information that is quantitative, qualitative, or behavioural.

5.22

For example, survey-based research by Johnson, Rochkind, and DuPont found that, in America, although judging performance using quantitative measures was a helpful performance management tool, being accountable to the public was a reciprocal relationship. It was more about responsible behaviours, ensuring fairness, acting honourably, listening to the public, and responding to people's concerns.109

Step 4 – The mechanism for debate: How should the account be given?

5.23

The fourth step is about ensuring that the accountability information is presented properly and that the account holder and account giver are able to understand, debate, and challenge that information if needed.

5.24

This can occur through various forums and involve mechanisms such as reporting, presentations, discussions, audits, panels, or reviews. It can be triggered by an event, a project start date, or as part of a regular reporting schedule. The account can simply be providing factual information. If the objectives are more about encouraging learning or promoting good behaviours, the account might be relational and personal in nature (such as face-to-face meetings).

5.25

Having an appropriate forum that provides the right mechanism for establishing public accountability is critical. For example, Bovens notes that public management methods, such as implementing quality control systems, benchmarks, or satisfaction surveys:

… do not constitute a form of accountability in themselves, as a relationship with a forum is lacking … and there is … no formal or informal obligation to account for the results, let alone a possibility for debate and judgement.110

5.26

In 2018, Heldt reviewed the World Bank's response to criticism that it was unaccountable and inefficient. The World Bank responded by creating more internal accountability forums and mechanisms, such as in-house evaluation groups, inspection panels, and compliance officer positions. Heldt argues that these internal solutions "paradoxically made the Bank even more encapsulated and less accountable to the outside world".111

5.27

If the accountability information is not presented properly, public accountability can become a compliance exercise with little usefulness or purpose. For example, Ebriham points out that "[s]imply identifying shortfalls in organizational performance and assuming that the information will be used by the organization to improve performance is insufficient for ensuring actual change".112

5.28

Manes-Rossi also warns that, if there is a lack of public engagement or participation initiatives, new reporting ideas, such as "integrated reporting" or "sustainability reporting", might simply be "cosmetic change."113

5.29

Public accountability cannot be established unless the accountability information is able to be properly understood, debated, challenged, and acted on. The public sector is responsible for achieving this in an appropriate and balanced way.

Step 5 – The judgement: What are the appropriate consequences?

5.30

The fifth step is about deciding whether, and what, consequences should apply as a result of the accountability arrangement. Consequences that are ambiguous, overemphasised, or not aligned with the objectives can create perverse behaviours and mistrust, rather than promoting good behaviours and public trust.

5.31

Two types of consequences are often discussed in the literature – punishment after an event has occurred and motivation or stimulus before an event has occurred. Which is more appropriate will usually depend on the level of trust between the account holder and account giver and the objectives of the accountability arrangement.

Punitive approaches

5.32

Mansbridge believes that using punishment can be warranted in situations where there is a justified level of distrust or suspicion.114 This could, for example, be in situations of public crisis, when dealing with organisations outside the public sector, or as a result of, as Johnson and others observe, the public not feeling reassured or trusting.115

5.33

Similarly, punishment might also be appropriate in situations where the objectives of the accountability arrangement are designed to control the relationship between parties or to discipline one party if expectations are not met.

5.34

Behn notes that, in government, "[a]ccountability means punishment" and that the inappropriate use of sanctions can result in excessively cautious behaviour. He observes that, when public officials are held accountable, "two things can happen: When they do something good, nothing happens. But when they screw up, all hell can break loose."116

5.35

On the other hand, Edwards notes that many citizens and some members of the media believe that there is a lack of appropriate punishment for senior public officials and politicians who make serious mistakes.117

Motivational approaches

5.36

Motivating and encouraging the account giver to demonstrate good behaviour might be a more appropriate approach when the nature of the relationship is more trusting, or when adaptability and learning are important objectives.

5.37

For example, Mansbridge argues that, where there is little justified distrust or suspicion, an alternative to punishment would be to focus more on the nature of the relationship, who it is with, and how the account is given.118 This could be the case where the interests of people or organisations align or they share a common goal.

5.38

Bovens, Schillemans, and 't Hart, in discussing how public accountability can motivate learning and improve public sector effectiveness, place more emphasis on a reflective and less punitive process. This involves regular feedback and debate with all stakeholders. Creating the right forum for debate is essential, and, to avoid any defensive behaviours, it must be safe for all parties.119

5.39

Schillemans and Smulders describe various conditions that, as part of the accountability process, should create more of a learning and innovative culture.120 These include ensuring that there is a high level of interpersonal trust between all parties and that, if errors are found, they are treated as opportunities and punishments are minimised.

Public accountability is not the solution to all problems

5.40

So far, we have focused on how public accountability can be planned for, managed, and evaluated effectively. However, focusing too much on public accountability can also create issues:

- An accountability dilemma can arise when management and governance decisions are heavily based on, or influenced by, compliance and/or manipulating accountability requirements.121

- An accountability paradox can arise when accountability requirements reduce organisational performance through, for example, higher costs, less responsiveness, a shorter-term focus, risk aversion, and less innovation.122

- A tyranny of light can arise when the desire for fully transparent and objective measures leads to complexity, lack of timeliness, less public understanding, secrecy concerns, less rational decision-making, and more public distrust.123 There is also the risk that "transparency will be seen as a ‘replacement' for real accountability".124

- A multiple accountabilities disorder can arise where a lack of clarity about what accountability means creates difficulties when organisations attempt to be accountable in the wrong way or try to be accountable in every way.125

- A problem of many eyes can arise when organisations have different stakeholders with different and conflicting accountability requirements.126

5.41

O'Neill captures the overarching issue by observing that "[p]lants don't flourish when we pull them up too often to check how their roots are growing".127

5.42

Public accountability is not a solution for all public sector issues. Care must be taken in how it is planned for and managed to avoid or mitigate unintended consequences on other public sector objectives. As Dubnick observes:

… [the many] promises of accountability … include unquestioned – and often unsubstantiated – assumptions that various forms of accountability will result in a more democratically responsive government, improvements in the efficient and effective performance of government agencies, a more ethical public sector workforce, and the enhanced capacity of government to generate just and equitable policy outcomes.128

5.43

As we noted in Parts 3 and 4, research also suggests that a primary or singular focus on performance can limit the ability of public accountability to maintain the public's trust and confidence in the public sector. Lægreid and Christensen observe that the relationship between performance and accountability is typically "characterized by tensions, ambiguities and contradictions".129

5.44

Other research supports the view that focusing too much on performance information can limit the effectiveness of public accountability. This can occur, for example, when:

- the information used fosters a narrow perspective on efficiency, objective measurement, or short-term results that do not align with people's wider longer-term expectations;

- auditing or reviewing performance becomes too compliance based;

- auditing or reviewing performance focuses on hierarchy and punishment, which can undermine trust;130 and/or

- other public accountability mechanisms and attributes are overlooked or not reported on, such as integrity, representation, and administration. Behn observes that "[b]y specifying purpose, measures, and targets, public executives create a specific bias for performance accountability. This is dangerous."131

5.45

Planning for, managing, and evaluating how the public sector is accountable to the public should be an integral part of the public sector's work, particularly when the relationship between the public and the public sector is changing. In the next Part, we consider how public accountability has changed over time and what this could mean for the future.

103: Sulu-Gambari, W (2014), Examining public accountability and policy issues in emerging economies: A case study of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Nigeria, PhD thesis, University of Manchester, page 34.

104: Bovens, M, Schillemans, T, and ‘t Hart, P (2008), "Does public accountability work? An assessment tool", Public Administration, Vol 86 Issue 1, page 226.

105: Bovens, M (2005), "Public accountability – A framework for the analysis and assessment of accountability arrangements in the public domain", draft made for CONNEX, Research Group 2: Democracy and Accountability in the EU, September 2005, page 7.

106: Ashworth, R and Skelcher, C (2005), "Meta-evaluation of the local government modernisation agenda", Progress report on accountability in local government, Centre for Local & Regional Government Research, Cardiff Business School, September 2005.

107: Mees, H and Driessen, P (2018), "A framework for assessing the accountability of local governance arrangements for adaptation to climate change", Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, February 2018, DOI: 10.1080/09640568.2018.1428184.

108: Gill, D (2000), "New Zealand experience with public management reform – or why the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence", International Public Management Journal, Vol 3 No 1, page 60.

109: Johnson, J, Rochkind, J, and DuPont, S (2011), Don't count us out, Public Agenda and the Kettering Foundation, pages 6 and 18-26.

110: Bovens, M (September 2005), "Public accountability – A framework for the analysis and assessment of accountability arrangements in the public domain", draft made for CONNEX, Research Group 2: Democracy and Accountability in the EU, page 10.

111: Heldt, E (2018), "Lost in internal evaluation? Accountability and insulation at the World Bank", Contemporary Politics, Vol 24 No 5, abstract.

112: Ebriham, A (March 2005), "Accountability myopia: Losing sight of organizational learning" Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, Vol 34 No 1, page 67.

113: Manes-Rossi, F (2019), "New development: Alternative reporting formats: a panacea for accountability dilemmas?", Public Money and Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2019.1578540, pages 3-4.

114: Mansbridge, J (2014), "A contingency theory of accountability", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, page 55.

115: Johnson, J, Rochkind, J, and DuPont, S (2011), Don't count us out, Public Agenda and the Kettering Foundation, pages 11-12.

116: Behn, R (2001), Rethinking democratic accountability, Brookings Institution Press, pages 3 and 14.

117: Edwards, B (2017), "Bryce Edwards analysis: The unaccountability of elites", Evening Report.

118: Mansbridge, J (2014), "A contingency theory of accountability", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, pages 55, 58, and 59.

119: Bovens, M, Schillemans, T, and ‘t Hart, P (2008), "Does public accountability work? An assessment tool", Public Administration, Vol 86 Issue 1, page 232.

120: Schillemans, T and Smulders, R (2015), "Learning from accountability?! Whether, what, and when", Public Performance and Management Review, Vol 39 No 1, pages 253-255.

121: Lægreid, P and Christensen, T (2013), Performance and accountability – A theoretical discussion and an empirical assessment, Stein Rokkan Centre for Social Studies, page 10.

122: Lægreid, P and Christensen, T (2013), Performance and accountability – A theoretical discussion and an empirical assessment, Stein Rokkan Centre for Social Studies, page 10.

Secretariat for State Sector Reform (November 2011), Better Public Services – Draft issues paper, page 6.

123: Dubnick, M and Frederickson, H (2011), Accountable governance – Problems and promises, Routledge, page 81.

124: The Centre for Public Scrutiny (2010), Accountability works!, page 23.

125: Koppell, J (2005), "Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of ‘multiple accountabilities disorder'", Public Administration Review, Vol 65 No 1, page 95.

126: Bovens, M (2005), "Public accountability – A framework for the analysis and assessment of accountability arrangements in the public domain", draft made for CONNEX, Research Group 2: Democracy and Accountability in the EU, September 2005, page 14.

127: O'Neill, O (2002), "Lecture 1: Spreading suspicion", Reith lectures: A question of trust, BBC, page 6 of transcript.

128: Dubnick, M (2012), "Accountability as cultural keyword", presentation at a seminar of the Research Colloquium on Good Governance Netherlands Institute of Government, page 5.

129: Lægreid, P and Christensen, T (2013), Performance and accountability – A theoretical discussion and an empirical assessment, Stein Rokkan Centre for Social Studies, page 10.

130: Lægreid, P and Christensen, T (2013), Performance and accountability – A theoretical discussion and an empirical assessment, Stein Rokkan Centre for Social Studies, page 10.

131: Behn, R (2014), "PerformanceStat", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, page 460.