Part 2: What do we mean by public accountability?

2.1

How the public sector supports public trust and confidence, and the role of public accountability in doing that, is not well understood. Although a lot of theory exists, there are few agreed concepts, frameworks, or guidance.

2.2

Before we can start to think about how to plan for and manage public accountability, we need to better understand why public accountability is important, the ways it can be established, and how the system of public accountability complements the system of public management.

Accountability has different meanings for different people

2.3

Haidt believes that accountability is fundamental at any time when people co-operate with other people they do not know.2 Accountability therefore can be seen to be as much about the relationship as it is about the responsibility (or task). Ultimately, it is about ensuring that people are able to trust each other to do what is expected of them.

2.4

Considering accountability from the perspective of the relationship means there can be different accountabilities between individuals or groups, and in many different contexts. Accountability can also have many different objectives. For example, one important accountability objective of health professionals is to ensure that their patients receive good medical treatment.

2.5

Different cultures can also emphasise different objectives. For example, one accountability objective for Māori communities is to ensure that their customs and behaviours are upheld and maintained across generations.

2.6

In teams of people, cultures of accountability can be more important than individual accountabilities. In fact, Katzenbach and Smith observe that "[n]o group ever becomes a team until it can hold itself accountable as a team".3 Rashid argues that, because teams of people must work together to pursue common goals, accountability within those teams can be more interpersonal and reciprocal. He uses the term mutual accountability to describe team members' evaluation of each member's progress in an "informal, unmediated, and even spontaneous" way.4

2.7

However, accountability does not just exist when co-operation is needed. It can also involve personal responsibility – for example, associated with religion or other beliefs, personal development goals, or ethical and moral values.

2.8

Individuals can experience or perceive accountability in a variety of ways. People can form personal expectations and attitudes through directly interacting with other people or when they use public services.5 Related to this is the idea of "felt accountability", the view that, among other things, "[i]ndividual behavior is predicated on perceptions of accountability".6

2.9

It is not surprising that international literature has identified many different definitions and descriptions of accountability. It has been researched as a medical, accounting, or legal concept, a virtue, and as a social or institutional arrangement.

2.10

In a public sector context, researchers have identified various types of accountability. These include political, legal, ministerial, democratic, bureaucratic, parliamentary, and social accountability. In practice, many related concepts are also associated with accountability, such as answerability, transparency, visibility, controllability, responsibility, or responsiveness. Accountability is also sometimes seen as simply providing an account.

2.11

These various terms can lead to conflict and tension in practice. Peters gives the example of a public official who may be given an order by his Minister (responsiveness) that they believe is illegal (responsibility).7 This order may also be inconsistent with their employment position (answerability) or have little to do with what the official provides to Parliament (giving an account).

2.12

Lupson observes that these different concepts "represent the source of much confusion about the concept of accountability".8 Koppell also argues that different accountability terminology can adversely affect organisational performance because what the organisation is ultimately accountable for can become confusing.9

2.13

With its many different dimensions and objectives, accountability remains in theory and in practice "ambiguous, complex, elusive, fragmented and heterogeneous".10 This has led to "much theory being generated but little by way of agreed concepts and frameworks".11

Public accountability in a representative democracy

2.14

Accountability has been described as "the hallmark of modern democratic governance".12 This is not a new idea. Benjamin Disraeli, a 19th century British politician, wrote "... that all power is a trust; that we are accountable for its exercise; that from the people and for the people all springs, and all must exist."13

2.15

Finn states that, "[w]here the public's power is entrusted to others", there is an important and overarching constitutional and fiduciary principle that "[t]hose entrusted with public power are accountable to the public for the exercise of their trust".14 Barnes and Gill also observe that the public's trust in the public sector is closely related to the level of confidence the public has in the public sector.15

2.16

According to Finn, being accountable to the public is an "obligation of all who hold office or employment in our governmental system".16 It is a "burden", Finn states, that is placed on the public sector when it accepts responsibility for exercising powers on behalf of the public.

2.17

These observations establish the importance of accountability in maintaining a trusting relationship with the public in a representative democracy. This has profound implications for how the public sector behaves and interacts with the public. For example, the New Zealand State Services Commission's code of conduct guidance acknowledges that "State servants are guardians of what ultimately belongs to the public, and the public expects State servants to serve and safeguard its interests".17

2.18

The public can judge trustworthiness at any time when, as Thomas and Min Su observe, the public interacts with the public sector as either a user, a partner, or ultimate owner of public sector resources.18 This is what Miller and Listhaug refer to as a "summary judgement"19 of the public sector's trustworthiness based on the public's expectations of how government should operate.

2.19

However, judging trustworthiness, as O'Neill warns, is difficult and subjective, but she points to competence, reliability, and honesty as useful attributes. O'Neill states:

… if we find that a person is competent in the relevant matters, and reliable and honest, we'll have a pretty good reason to trust them, because they'll be trustworthy.20

2.20

We agree that public accountability comes from the need for a trusting relationship between the public sector and the public. It is about the public sector demonstrating its competence, reliability, and honesty in a way that allows the public to judge its trustworthiness in using public money and resources.

2.21

This is the definition of public accountability we use in this paper. It provides a more citizen-centred perspective of public sector accountability in a representative democracy. It also suggests, as the New Zealand State Services Commission has argued, that "[a]ccountability goes beyond, for example, only being accountable to the law, or to the government of the day, or to a superior, as critical as these are to understanding accountability in the public sector".21

Avenues of public accountability

2.22

Our explanation of public accountability in the public sector assumes that it is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. This is consistent with Greiling's view, who explains that public accountability can be seen as "an instrument which signals competence and organizational trustworthiness".22

2.23

If public accountability is about maintaining a trusting relationship between the public sector and the public, then the way the public sector interacts with the public is also important.

2.24

How the public sector interacts with the public depends on a range of factors, including: the form of democracy, the way the public sector is organised and managed, and, importantly, the make-up and expectations of the public. Mulgan observes that, where there is:

… a range of different groups and individuals with differing values and interests and different organisational means of interrelating with government [this can mean] the accountability of government to the people sensibly requires a range of alternative channels …[or]… avenues.23

2.25

Ranson and Stewart also argue that:

… [i]n the diversity of a learning society, public accountability requires many channels by which accounts are given and received and a clear line by which those who exercise collective choice are held to account.24

2.26

Finn refers to different avenues through which public accountability can be established. These are indirectly, through institutions such as Parliament and the Auditor-General and through superiors or peers, and directly with the public.25

Indirect avenues

2.27

Indirect avenues use representatives of the public to hold the public sector accountable.

2.28

New Zealand's public accountability system could be seen as largely indirect. It is built on the separation of three branches of government – the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. These three branches act as a check on each other to prevent concentrations and/or abuses of power by the state over its people.26

2.29

The legislature is Parliament, also known as the House of Representatives. It is the ultimate representative of the people. The executive includes the government of the day, its agencies, and public officials. The judiciary include judges and other judicial officers.

2.30

Joseph notes that, under our constitutional system, being a "responsible government" means that Ministers are collectively responsible to Parliament for the overall performance of government and individually responsible for the performance of their portfolios.27

2.31

Public officials and their agencies act for, and are accountable to, their Minister. This relationship links "political desire to action" 28 and relies on three crucial elements: the public official's loyalty to the government of the day, political neutrality, and anonymity from the public's gaze.29

2.32

The Treaty of Waitangi is also an integral part of New Zealand's constitutional arrangements. According to the Waitangi Tribunal, this Treaty relationship, among other things, means "a proper engagement between the Crown and Māori, a sharing of power and control over resources, a mutual accountability, where the relationship harnesses the potential of all Māori in the most effective manner".30

2.33

Constitutional accountability arrangements within the executive and between the executive and the legislature are structured as a vertical, single-point chain of separate accountabilities that flow from the public officials to Parliament.31 Usually referred to as the "Westminster chain", it is indirect because the public is represented at each step by different parties, with Parliament being the ultimate representative.

2.34

Under the Westminster system, public officials and their agencies are not directly accountable to the public or to Parliament.32 Members of Parliament are directly accountable to the public through general elections.

2.35

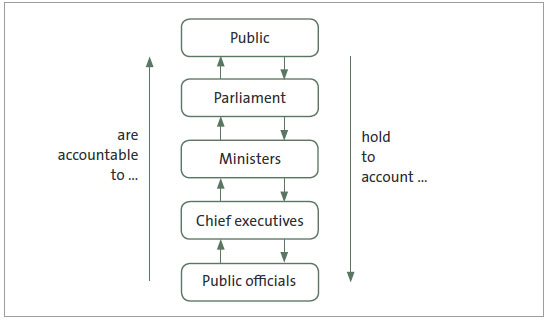

Figure 1 portrays the Westminster chain in a New Zealand context, where chief executives sit between public officials and Ministers.

2.36

Over time, this chain has acquired new and different links as other organisational forms have been created and new ways of delivering public services have emerged. For example, various types of Crown entities have been set up to provide varying levels of operational distance from government. For many forms of Crown entity, chief executives are employed by, and are accountable to, the entities' governance boards. These boards are then accountable to Ministers. Public private partnerships between the public sector and the private sector also establish other lines of accountability outside the "chain".

Figure 1

The Westminster chain of public accountability

Public officials are held accountable to the public through chief executives, Ministers, and ultimately Parliament.

Source: Adapted from: Stanbury, W (2003), Accountability to citizens in the Westminster model of government: More myth than reality, Roy, J (2008); "Beyond Westminster governance: Bringing politics and public service into the networked era"; and State Services Commission (1999), "Improving accountability: Setting the scene".

2.37

Many agencies that carry out public accountability functions on behalf of Parliament support and surround this chain. These include the three officers of Parliament – the Auditor-General, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, and the Ombudsman. Some of these functions include ensuring that annual reports are a true and fair reflection of the activity and performance of public organisations and investigating public sector conduct or complaints.

2.38

In addition, many other agencies within the chain also have monitoring functions, including the Treasury, the State Services Commission, the Tertiary Education Commission, the Serious Fraud Office, and the Commerce Commission. Some of these functions include reporting on entity and sector performance and ensuring that the public's money is budgeted, properly authorised, and properly allocated.

2.39

The large network of public sector review agencies and monitoring teams that support Parliament and the public is a feature of the New Zealand public accountability system. Although this large network might seem beneficial, overemphasising public accountability can lead to complexity and confusion (see Part 5).

2.40

An Auditor-General's report in 2016 identified 90 inquiry agencies responsible for administering various accountability functions. However, we could not find an explanation or guide that helped make sense of the various accountability functions in New Zealand.33

2.41

Whether these indirect avenues are enough in today's more open, dynamic, and connected world is an important question. We explore this question further in Part 4.

Direct avenues

2.42

Direct avenues are where the public or sections of the public (directly) hold the public sector accountable.

2.43

In New Zealand, direct public accountability avenues are becoming increasingly important. In commenting on the recently announced State sector reforms, Ryan observes that "citizens are now demanding more direct accountability of public officials" and that this is something the Westminster system never envisaged.34 Hare also argues that, in New Zealand, "Chief executives have responsibilities for which they are personally answerable to the media and the public."35

2.44

Direct public accountability can take place, in whole or in part, through avenues such as general and local body elections, referendums, social media, special interest group scrutiny, consultation and complaints processes, the Official Information Act 1982, and the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987.

2.45

Elements of direct accountability are also found, for example, in increased public participation in policy development, a greater focus on engaging the public in delivering front-line services, and more public reporting through social and other media channels. Many public sector agencies have dedicated media and communications teams to help ensure that a wide range of audiences can understand public reporting. As we discuss in Part 5, all these elements are important, but not necessarily enough, to establish public accountability.

2.46

For some time, local authorities in New Zealand have also been required to directly consult with their communities about future rates increases and their long-term infrastructure and financial strategies.

2.47

We recently reported on our audits of councils' 2018-28 consultation documents. We discussed the challenges councils face in understanding different stakeholders in their communities, presenting complex information, and responding to the feedback they receive.36 As an example, Grey Power Auckland believes that the information included in Auckland Council's long-term plan consultation documents is so complex that it is difficult for ordinary people to take part in the public consultation process.37

2.48

For Māori, direct accountability to the community is as important as other more formal accountability mechanisms. For example, the Waitangi Tribunal quoted Sharples as saying that "[a]ccountability is in terms of one, the constitution, in terms of what the trustees have to do formally; and there's another kind of accountability which is your personal accountability to the people generally … and that … there is, in people fronting up, an accountability to the people, as well as their requirements in terms of the legal constitution".38

2.49

Examples of more direct public accountability in other countries include:

- a "semi-direct" or "liquid" form of democracy in Switzerland, which is representative (indirect) but also allows citizens to regularly shape legislation and constitutional changes through various direct accountability forums that include referendums and "popular initiatives" where the people propose the change;

- direct public voting on budgets in Brazil and the ability to draft laws online in Finland; and

- an online and open consultation process for the entire society to engage in rational discussion on national issues in Taiwan.39 The aim of "vTaiwan" is to help lawmakers implement decisions with a greater degree of legitimacy by bringing together government ministries, elected representatives, scholars, experts, business leaders, civil society organisations, and citizens.40

In practice, there can be a spectrum of direct and indirect features

2.50

As we previously saw with the Westminster chain, avenues can have features of both direct and indirect accountability. For example, the media can be a direct avenue when it publishes press releases from public organisations and an indirect avenue when it advocates for a particular position or stance. Public accountability through scrutiny by special interest groups can also have elements of direct and indirect accountability.

2.51

It is also possible for the public sector to be accountable to the public through more than one avenue. For example, a public organisation and its responsible Minister can be directly accountable to the public for the quality of services and indirectly accountable through Parliament and other agencies for how well it is administered.

Public accountability and public management

2.52

The "public accountability system" brings together principles, procedures, regulations, institutional arrangements, and participants to enable effective public accountability. A system that is clear, is coherent, and works well will contribute to a clear judgement or perception of public sector trustworthiness.

2.53

How the public sector is accountable, as Transparency International puts it, "for their exercise of power, for the resources entrusted to them, and for their use of those resources"41 is not the same as how the public sector manages itself. Simply put, the public accountability system supports public trust and confidence, while the public management system supports the delivery of the right public services in the right way at the right time.

2.54

However, the two systems are closely related. As Bovens observes, "[p]ublic accountability, as an institution, therefore, is the complement of public management".42

2.55

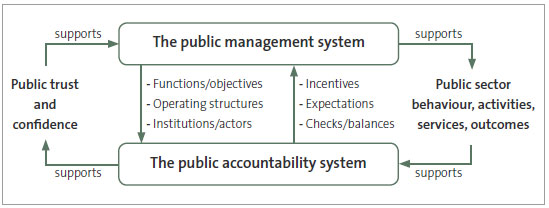

Figure 2 summarises how the public accountability system complements and interacts with the public management system.

2.56

By supporting public trust and confidence, the public accountability system helps provide the "social licence" needed for the public management system to deliver public services. The public accountability system also supports the development of trust within the public management system by establishing expectations for people (and teams of people), providing the necessary checks and balances, and encouraging proper behaviours and cultures.

Figure 2

The relationship between the system of public accountability and the system of public management

The public accountability system helps support public trust and confidence and complements the public management system.

2.57

While separate, the two systems are highly interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Both seek a public sector that operates in a competent, reliable, and honest way, and these attributes are as important to public management as they are to public accountability.

2.58

These interrelationships are also found in Moore's "public value" framework of public management. The framework recognises that public trust and confidence in the public management system increases as public value is created and demonstrated, and that this in turn provides the necessary legitimacy and public support to increase the operational capacity of the public sector further.43

2.59

The level of trust and confidence the public has depends on how well the public accountability system works with the public management system to demonstrate the public sector's competence, reliability, and honesty.

2: Haidt, J (2012), The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion, Penguin UK, page 87.

3: Katzenbach, J and Smith, D (1993), "The discipline of teams", Harvard Business Review, March-April Issue 1993, page 168.

4: Rashid, F (2015), Mutual accountability and its influence on team performance, PhD thesis, Harvard University, pages 3, 8, and 9.

5: Dowdle, M (2006), "Public accountability: Conceptual, historical, and epistemic mappings", Regulatory theory: foundations and applications, ANU Press, pages 205-207.

6: Overman, S et al (2018), "Comparing governance, agencies and accountability in seven countries", a CPA survey report, page 14.

7: Peters, G (2014), "Accountability in public administration", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, page 215.

8: Lupson, J (February 2007), A phenomenographic study of British civil servants' conceptions of accountability, PhD Thesis, Cranfield University, page 34.

9: Koppell, J (2005), "Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of ‘multiple accountabilities disorder'", Public Administration Review, Vol 65 No 1, page 95.

10: Greiling, D and Spraul, K (2010), "Accountability and the challenges of information disclosure", Public Administration Quarterly, Fall issue, page 1.

11: Smyth, S (2007), "Public accountability: A critical approach", Journal of Finance and Management in Public Services, Vol 6 No 2, page 31.

12: Bovens, M (2005), "Public accountability", in Ferlie, E et al (eds), The Oxford handbook of public management, Oxford University Press, page 182.

13: Disraeli, B (1826), Vivian Grey: A novel, page 206.

14: Finn, P (1994), "Public trust and public accountability", Griffith Law Review, Vol 3 No 2, page 228.

15: Barnes, C and Gill, D (February 2000), "Declining government performance? Why citizens don't trust government", State Services Commission Working Paper No 9, page 4.

16: Finn, P (1994), "Public trust and public accountability", Griffith Law Review, Vol 3 No 2, page 233.

17: State Services Commission (2010), Implementing the code of conduct – Resources for organisations, page 3, at www.ssc.govt.nz.

18: Thomas, J and Min Su (2013), "Citizen, customer, partner: What should be the role of the public in public management in China?", a paper for the UMDCIPE conference on Collaboration among Government, Market, and Society, 26 May 2013, pages 1-2.

19: Miller, A and Listhaug, O (1990), "Political parties and confidence in government: A comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States", British Journal of Political Science, Vol 20 Issue 3, page 358.

20: O'Neill, O (June 2013), "What we don't understand about trust" (video), www.ted.com.

21: State Services Commission (1999), "Improving accountability: Setting the scene", Occasional Paper No 10, page 8.

22: Greiling, D (2014), "Accountability and trust", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, page 624.

23: Mulgan, R (March 1997), "The processes of public accountability", Australian Journal of Public Administration, pages 26 and 29.

24: Ranson, S and Stewart, J (1994), Management for the public domain: Enabling the learning society, St. Martin's Press, page 241.

25: Finn, P (1994), "Public trust and public accountability", Griffith Law Review, Vol 3 No 2, pages 234 and 235.

26: See www.justice.govt.nz and New Zealand Legislation Design and Advisory Committee (2018), Legislation guidelines, page 22.

27: Joseph, P (2014), Constitutional and administrative law in New Zealand, fourth edition, Brookers Ltd, page 13.

28: James, C (2002), The tie that binds, Institute of Policy Studies and the New Zealand Centre for Public Law, page 1.

29: James, C (2002), The tie that binds, Institute of Policy Studies and the New Zealand Centre for Public Law, pages 7-10.

30: The Waitangi Tribunal (1998), The Te Whanau o Waipareira report, GP Publications, page 128.

31: Stanbury, W (2003), Accountability to citizens in the Westminster model of government: More myth than reality, Fraser Institute Digital Publication, page 11.

Roy, J (2008), "Beyond Westminster governance: Bringing politics and public service into the networked era", Canadian Public Administration, Vol 51 No 4, page 545.

State Services Commission (1999), "Improving accountability: Setting the scene", Occasional Paper No 10. Trenorden, M (2000), "Public sector attitudes to parliamentary committees – A chairman's view", Australasian Parliamentary Review, Vol 16(2), page 98.

32: Stanbury, W (2003), Accountability to citizens in the Westminster model of government: More myth than reality, Fraser Institute Digital Publication, page 11. Roy, J (2008), "Beyond Westminster governance: Bringing politics and public service into the networked era", Canadian Public Administration, Vol 51 No 4, page 545.

33: Office of the Auditor-General (2016), Public sector accountability through raising concerns, page 14.

34: Ryan, B (2018), Submissions to the State Services Commission on the proposed reform of the State Sector Act 1988, page 273.

35: Hare, L (2004), "Ministers' personal appointees: Part politician, part bureaucrat", New Zealand Journal of Public and International Law, Vol 2 No 2, page 328.

36: Office of the Auditor-General (2018), Long-term plans: Our audits of councils' consultation documents.

37: Office of the Auditor-General (2018), Long-term plans: Our audits of councils' consultation documents, pages 21-22.

38: The Waitangi Tribunal (1998), The Te Whanau o Waipareira report, GP Publications, page 66.

39: See vTaiwan: info.vtaiwan.tw/.

40: Matthews, P (2018), "National portrait: Max Rashbrooke" at www.stuff.co.nz, 29 September 2018, referencing Rashbrooke, M (2018), Government for the public good: The surprising science of large-scale collective action, Bridget Williams books.

41: Transparency International New Zealand (2018), New Zealand national integrity system assessment – 2018 update, page 24.

42: Bovens, M (2005), "Public accountability", in Ferlie, E et al (eds), The Oxford handbook of public management, Oxford University Press, page 182.

43: Kavanagh, S (October 2014), "Defining and creating value for the public", Government Finance Review, page 57, and Kelly, G, Mulgan, G, and Muers, S, "Creating public value – An analytical framework for public service reform", a discussion paper by the UK Cabinet Office, page 10.