Part 3: Why public accountability is important

3.1

We consider the need for public accountability arises because of the need for a trusted relationship between the public sector and the public. It is about the public sector demonstrating its competence, reliability, and honesty in a way that allows the public to judge the trustworthiness of the public sector in using public money and resources.

3.2

This Part explores why public trust and confidence are important in the first place, what influences them, and whether they can be maintained.

The importance of public trust and confidence

3.3

When Confucius was asked about government by his disciple Zigong more than 2000 years ago, he said three things were needed for government: weapons, food, and trust. If a ruler cannot hold on to all three, he should give up weapons first then food. However, trust should be guarded to the end because "without trust we cannot stand".44

3.4

According to the Treasury, trust is an important part of maintaining New Zealand's "social capital".45 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) observes that:

… [t]rust is essential for social cohesion and well-being as it affects governments' ability to govern and enables them to act without having to resort to coercion … A decline in trust can lead to lower rates of compliance with rules and regulations. Citizens and businesses can also become more risk-averse, delaying investment, innovation and employment decisions that are essential to regain competitiveness and jumpstart growth.46

3.5

In a representative democracy, where "the public's power is entrusted to others",47 maintaining the public's trust and confidence is a fundamental responsibility of the public sector.

3.6

The importance of maintaining the public's trust and confidence is central to the purpose and outcomes of many public organisations in New Zealand. According to the State Services Commission, the "Public Service must work with the highest standards of integrity and conduct to ensure the trust and confidence of New Zealanders is maintained".48 Public sector organisations such as Auckland Council, the Accident Compensation Commission, the New Zealand Police, and the Serious Fraud Office all carry out surveys of public trust and confidence.

Building public trust and confidence

3.7

Although public trust and confidence are important, O'Neill observes that we should not necessarily strive for more trust everywhere. Instead, "[i]ntelligently placed trust" should be the goal, which requires "judging how trustworthy people are in particular respects".49

3.8

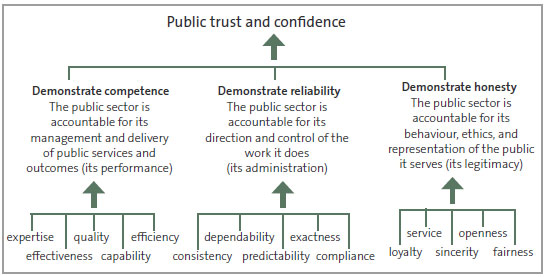

Public trust and confidence is built and maintained by the public sector demonstrating competence, reliability, and honesty. To illustrate what these three attributes mean in practice:

- Competence can include the qualities of expertise, performance, capability, efficiency, and effectiveness.

- Reliability can include the qualities of exactness, consistency, compliance, predictability, and dependability.

- Honesty can include ethical or behavioural qualities of truthfulness, loyalty, faithfulness, service, openness, fairness, and sincerity.

3.9

Integrity is also an important influencer of public trust and confidence. Integrity is a wide-ranging concept that shares many of the qualities of competence, reliability, and honesty. It is about consistently adhering to strong moral and ethical principles. High levels of integrity are associated with low levels of corruption, which is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.50

3.10

The idea that competency, reliability, and honesty are central to public trust and confidence is well supported. For example:

- Miller and Listhaug observe that assessing trust in government is a "summary judgement" that the system is "fair, equitable, honest, efficient and responsive to society's needs" even without constant scrutiny.51

- Van Ryzin found "growing evidence from various fields that trust in people and institutions of authority often depends more on process (such as fairness and equity) than on outcomes".52

- Bouckaert, in discussing the importance of performance in building trust in government, also recognises that:

… improving service delivery is necessary but not sufficient for trust … and that … Good performance does not necessarily lead to more trust, but bad performance certainly will erode trust.53

- A State Services Commission working paper explains that trust in government is about the level of confidence citizens have in their government "to ‘do the right thing', to act appropriately and honestly on behalf of the public".54 One of the questions asked in the State Services Commission's Kiwis Count survey is "Thinking about your most recent service contact, can you trust [public servants] to do what is right?"55

- A paper prepared in 2015 for the Committee of Experts on Public Administration noted that the many definitions of trust in government included common characteristics:

… the fostering of participatory relationships; perceptions of competence; meeting performance expectations; keeping promises; ‘doing what is right'; and, maintaining a law-abiding society.56

3.11

Bouckaert and Van de Walle observe that "[t]he factors determining trust in government are not necessarily the same for every country or political culture".57 We agree. New Zealand's public accountability system has to adapt to a society that is becoming increasingly diverse. We explore this further in Parts 6 and 7.

3.12

In 2012, we asked New Zealanders what factors were important in trusting or not trusting public organisations. Figure 3 categorises the responses that related to competence, reliability, and honesty. Most of these related to the attributes of reliability and honesty.

Figure 3

Important factors in trusting or not trusting public organisations – responses to our 2012 survey

Most responses related to the attributes of reliability and honesty.

| Responses that related to competence | Responses that related to reliability | Responses that related to honesty |

|---|---|---|

| "skilled personnel" | "checks are in place" | "corruption" or "not corrupt" |

| "past performance" | "wasting money" | "public servants are well intentioned" |

| "poor decision-making" | "bureaucracy" "red tape" |

"politically neutral" "people/bodies with their own agenda" |

3.13

The focus by the public on honesty was also highlighted at a 2018 Audit New Zealand client update, where the Deputy Auditor-General asked a group of public officials "What was more damaging to public trust and confidence – poor performance or poor behaviour?" Of the 191 respondents, 176 said it was poor behaviour.

3.14

These simple examples suggest that, for a public accountability system to be effective, it should demonstrate all three attributes. Focusing on only one attribute is not enough to build and maintain public trust and confidence.

How public accountability maintains public trust and confidence

3.15

How much trust and confidence the public has in the public sector depends on many factors and not just the effectiveness of the public accountability system. However, the public sector has a particular ability to influence the public accountability system and shape how it operates in practice. It plays a fundamental part in how the public sector helps to maintain public trust and confidence.

3.16

Figure 4 shows how honesty, competence, and reliability improve public trust and confidence. Greiling reminds us that this is not just a one-way relationship, and that some trust is a necessary prerequisite for effective public accountability to take place.58

Figure 4

How competence, reliability, and honesty influence public trust and confidence

The public sector should demonstrate competence, reliability, and honesty to maintain and improve public trust and confidence.

Source: Adapted from Greiling, D (2014), "Accountability and Trust".

3.17

All three attributes and their associated accountabilities are needed to build public trust and confidence. This means that it is particularly important for the public sector to ensure that it has effective accountability mechanisms to demonstrate these attributes.

3.18

However, depending on the state of the public sector, the expectations of the public or the nature of the accountability relationship, one or more attributes might need emphasising. For example, the results of the Auditor-General's survey indicate that demonstrating honesty and reliability are particularly important to New Zealanders in building public trust and confidence.

3.19

In practice, potential trade-offs can also arise. For example, overemphasising reliability (or effective administration) can lead to more "red-tape", which could adversely affect competence (or good performance).

3.20

Similarly, overemphasising performance can have perverse effects on honesty and openness. For example, publishing league tables can be good for promoting and managing organisational performance59 but some suggest it can also undermine the trust and confidence of public officials, leading to defensive, and sometimes perverse, working behaviours.60 Finding the right balance is crucial to ensuring that the accountability system achieves its objectives.

44: Yu, K, Tao, J, and Ivanhoe, P (2010), Taking Confucian ethics seriously: Contemporary theories and applications, SUNY Press, Albany, page 99.

45: For more information on the Treasury's Living Standards Framework and the Four Capitals, see treasury.govt.nz.

46: OECD (2013), Government at a glance 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, page 21.

47: Finn, P (1994), "Public trust and public accountability", Griffith Law Review, Vol 3 No 2, page 228.

48: State Services Commission (2018), State Services Commission Annual Report 2018, page 10.

49: O'Neill, O (June 2013), "What we don't understand about trust" (video), www.ted.com.

50: Transparency International New Zealand (2018), New Zealand national integrity system assessment – 2018 update, page 396.

51: Miller, A and Listhaug, O (1990), "Political parties and confidence in government: A comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States", British Journal of Political Science, page 358.

52: Van Ryzin, GG (October 2011), "Outcomes, process, and trust of civil servants", Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol 21 Issue 4, abstract.

53: Bouckaert, G (2012), "Reforming for performance and trust: Some reflections", The NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, Vol V No 1, page 18.

54: Barnes, C and Gill, D (February 2000), "Declining government performance? Why citizens don't trust government", SSC Working Paper No 9, page 4.

55: State Services Commission (2017), Kiwis Count: December 2017 Annual Report, page 7.

56: Committee of Experts on Public Administration (2015), "Building trust in government in pursuit of the sustainable development goals: What will it take?", fourteenth session, 20-24 April 2015, page 2.

57: Bouckaert, G and Van de Walle, S (2003), "Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of ‘good governance': Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators", International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol 69 Issue 3, page 6.

58: Greiling, D (2014), "Accountability and Trust", in Bovens, M, Goodin, R, and Schillemans, T, The Oxford handbook of public accountability, Oxford University Press, pages 623-626.

59: Bevan, G and Wilson, D (July 2013), "Does ‘naming and shaming' work for schools and hospitals? Lessons from natural experiments following devolution in England and Wales", Public Money and Management, page 245.

60: Davies, H and Lampel, J (1998), "Trust in performance indicators?", Quality in Health Care, Vol 7 Issue 3, pages 161-162.