Part 4: Financial pressures in institutes of technology and polytechnics

Summary of our observations

4.1

As well as drawing attention to going concern issues at two ITPs, our reporting to the councils of several other ITPs highlighted increasing financial pressures.

4.2

In our view, financial sustainability is the most significant challenge for many of the TEIs, but in particular the ITPs. These financial challenges are contributing to a climate of pressure that can increase risks to the delivery of high-quality education and training for students.

4.3

The main causes of those pressures were:

- declining domestic student enrolments;

- changes in international student participation in New Zealand tertiary education;

- operating costs increasing while revenue was declining; and

- the effects of previous decisions to invest in assets, made when revenue was higher.

4.4

ITPs need to improve their financial forecasting, governance oversight of financial controls, and investment in assets.

Declining revenue from domestic full-time students

4.5

The number of domestic students has been declining overall for some years. TEC analysis shows that the number of domestic students has fallen by a third in the last 10 years. The TEC notes that more young people are choosing to directly enter the labour market or choosing to stay longer at secondary school.

4.6

The TEC allocates government funding to TEIs based on domestic full-time student enrolments set out in their investment plans. This Student Achievement Component funding is agreed in advance, based on projected enrolments in TEIs' investment plans, and revised as actual enrolment data becomes available.

4.7

If data gathered during the year suggests that a TEI will fail to achieve the agreed number of enrolments, an "in-plan" adjustment is made to reduce the amount of funding due. If the funding has already been paid, the TEI needs to repay any overfunded amount to the TEC.9 In some instances, amendments during the year can increase funding because of higher demand. The TEC determines the final funding amounts, along with any repayments, after the end of the year, when TEIs submit their final enrolment data.

Observations from our audits

4.8

Nationally, about 200,000 domestic full-time students enrolled10 in TEIs in 2017, which is about 7000 fewer than the number of domestic full-time student enrolments in 2016.

4.9

The decrease of more than 7000 domestic student enrolments was not evenly spread between the three types of TEIs or within them. Domestic full-time student enrolments declined by 1243 at universities, by 555 at wānanga, and by 5356 at the ITPs. Only the University of Canterbury and Te Wānanga O Raukawa had more domestic students in 2017 than in 2016.

4.10

In our view, some of the enrolment projections we have seen in the investment plans are overly optimistic, and some TEIs are not meeting their forecasts in successive years. As Crown entities, TEIs are responsible for the quality of the information and forecasts they produce. However, we understand that the TEC is increasingly challenging the basis for these projections.

Changes in international student participation in New Zealand tertiary education

4.11

TEIs have historically made up all, or some, of the shortfall in revenue from declining domestic student numbers by attracting international students who pay full fees. Attracting international students has been part of the Tertiary Education Strategy 2014-2019.

4.12

Figure 4 shows that, overall, Immigration New Zealand issued 46,685 student visas to first-time, full-fee-paying international students in 2017/18.11 This was 1453 fewer than in 2016/17, but the fourth highest in the last 10 years. The total number of visas approved for students from all nations except for China and India was just more than 30,000, the highest in the last nine years. We show these nations separately because they have been the largest and second-largest nationalities accessing education in New Zealand in the recent past.

Figure 4

Number of visas approved for first-time, full-fee-paying students, by nationality and year, 2008/09 to 2017/18

First-time student visas for Chinese students dropped by about 18% in 2017/18. The decrease in first-time student visa approvals for Indian students started in 2015/16.

Source: Immigration New Zealand. Note: School-age children of other visa holders have a special category of visa (a dependent child student visa) and are not included in these figures.

4.13

Figure 4 also shows the decrease in visa approvals for Indian students started in 2015/16. In 2014/15, there were 13,248 first-time student visa approvals, 11,422 in 2015/16, and 7735 in 2016/17. Education New Zealand considers that most of this decrease was students who might have otherwise intended to study at private training establishments. However, a number of ITPs also had fairly high exposure to changes in demand from India.

4.14

The number of approved first-time student visas for 2017/18 was marginally higher at 7942. Recent information from Education New Zealand suggests first-time student visa approvals for Indian students have now stabilised.

4.15

The other country that provides a large number of international students is China. Figure 4 shows that approvals of first-time student visas for Chinese students dropped by about 18% in 2017/18. The number of visas approved is now just below the number of approvals for study visas in 2014/15.

4.16

An independent analysis by the ICEF Monitor12 highlights that "the college-aged population in China – that is, the 18-24-year-old group – is projected to decrease by more than 40%, from 176 million to 105 million, between 2010 and 2025". The Government stated in its International Education Strategy 2018-2030 that it expects the number of Chinese students to decrease further after 2025.13 The Government also expects that some countries will move from being providers of international students to providing tertiary education in their own countries. This means that there will be increased competition for international students. Education New Zealand highlights that there is not a single cause for the recent reduction in visa approvals for Chinese students.

4.17

The New Zealand International Education Strategystated that the quality of New Zealand's education experience should be a priority. The Government also announced changes to post-study work visa entitlements. The full effect of the strategy and of the visa changes might not be apparent until the 2019 enrolment numbers are released.

Observations from our audits

4.18

In 2017, 1051 more international full-time students enrolled to study in New Zealand than in 2016, but that increase was not evenly distributed among the TEIs.

4.19

Seven of the eight universities attracted more full-fee-paying international students in 2017 than in 2016, with the number of full-fee-paying international students up by 1129 or 6.9%.

4.20

Overall, there were 12,461 full-fee-paying international students studying at ITPs in 2017, a number largely unchanged from 2016. However, Southern Institute of Technology, Eastern Institute of Technology, and Otago Polytechnic had significant increases, while nine ITPs had fewer students than expected.

Why accurately forecasting student numbers is important for ITPs

4.21

Student numbers are a critical element of forecasts. Some ITPs were optimistic when forecasting the likely number of student enrolments. For example, projections for increases for domestic or international students looked optimistic compared to previous trends and some related indicators of future demand. These related indicators, such as the unemployment rate and first-time international student visa approvals, are updated regularly.

4.22

Councils need to be aware of this optimism bias and the risks it carries. In our view, some ITPs have been slow to reflect foreseeable changes in demand.

4.23

Councils should be ensuring they get good quality financial forecasts that include well-evidenced trend and risk analysis at the local, regional, national, and international level. As part of the forecasting information, TEIs should be preparing possible scenarios and carrying out sensitivity analysis on those scenarios.

4.24

Although some of the ITPs' delivery costs will vary depending on the number of students, many costs are fixed, such as staff costs and course development costs. If the ITP does not attract as many students as it forecast, it will incur losses.

4.25

It is important that the ITP understands the factors behind demand for its courses and does not over-invest in capacity that might not be needed. This means maintaining a good understanding of what students want, what employers want, what other ITPs are offering, and the ITP's likely share of that demand.

Operating costs increasing while revenue is declining

Observations from our audits

4.26

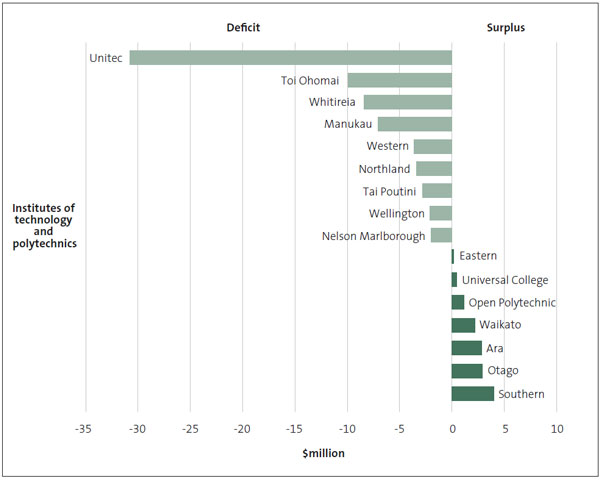

We looked at actual 2017 group surplus or deficit results against what the ITPs expected to achieve – their budgeted surplus or deficit.

4.27

Twelve of the sixteen ITPs did not achieve their budgets for 2017, up from eight in 2016.

4.28

The main reason for budget shortfalls was ITPs not achieving the forecast number of enrolled students. When those enrolments fell short of targets, the ITPs affected did not receive as much funding as they had expected. They had often committed to spending based on the expected number of student enrolments.

4.29

Some ITPs have not been quick to adjust their spending in line with falling income, spending more than planned on expenses at the same time that revenue was decreasing. This has eroded the financial "headroom", or working capital, those ITPs need to be able to invest in meeting the changing expectations of students and employers.

4.30

Working capital is the amount of readily available cash, or assets that can quickly be turned into cash, to pay liabilities due in the next 12 months. A working capital ratio of one or more means the ITP has enough funds from its current assets to pay for its current liabilities. A ratio of less than one means current liabilities exceed current assets, and the ITP might struggle to pay its debts when they are due. The TEC sets an indicator for this ratio in its financial monitoring framework (which it calls the quick ratio) of 1.5. Eleven ITPs have a quick ratio of less than 1.5.

Why is financial monitoring important?

4.31

Good financial monitoring should enable the ITPs to make changes during the year if the number of enrolments falls. ITP councils need to be satisfied that financial management controls, including budget monitoring and variance reporting, are working well.

4.32

Our analysis indicates that most ITPs struggle to align their operational costs to changes in revenue that happen during the year. For some ITPs, this is probably less concerning in the short-term – but, for ITPs that already have low working capital, it can be a significant issue.

4.33

Positive working capital is not just important for paying bills when they are due. It also provides ITPs with some flexibility to make changes to their operations – for example, increasing expenditure in the short term (such as redundancy payments or retraining costs) to achieve long-term savings.

4.34

Having low working capital does not mean the ITP is insolvent; it might have significant non-current assets, access to overdraft or loan facilities, and healthy capital reserves. But low working capital can mean ITPs need to borrow money to support current operations while organisational changes are made, and this adds to their overall operational costs. We have noted in some of our audits that ITPs are borrowing to meet operational costs and the costs of organisational change, rather than for investments in long-term assets. In our view, this is unsustainable where the return from organisation change takes too long to achieve.

Investment decisions

4.35

In 2017, we published a report Investing in tertiary education assets. For that report, we analysed 14 business cases for investments in assets that TEIs had prepared in 2013 and 2014.

4.36

The business cases were generally of a high standard. Benefits, risks, and risk-management approaches for the individual university or polytechnic were usually described in detail, and most sections dealing with risk included comments about a range of financial indicators.

4.37

However, there was little evidence of the aim in the Tertiary Education Strategy 2014-2019 to improve the effectiveness of the sector as a whole. In most of the business cases, TEIs did not take account of the investments planned or made by other TEIs, nor did they consider how to make the most of their investments by sharing or using the existing assets of other TEIs.

4.38

We reported that, in our view, there was an opportunity for more sector-based investment decisions. However, some TEIs believed that a competitive funding model and regulatory environment made it unlikely that they would work together to improve the efficiency of their investments in assets. Others pointed to examples where joint investments had been successfully made and the complexities of the funding and regulatory environment were worked through. These diverse views posed both a challenge to the implementation of the Tertiary Education Strategy 2014-2019 and an opportunity for the sector to consider how to better give effect to the strategy through their investment decisions.

Observations from our audits

4.39

During 2017, many TEIs had major campus development projects under way or planned. We noted a substantial amount of spending as TEIs implemented plans to maintain and develop their campuses.

4.40

Only a few TEIs were collaborating on campus investments, such as Wellington Institute of Technology and Whitireia Community Polytechnic's arrangement for the Te Kāhui Auaha creative campus in Wellington.14 Lincoln University, with government support, is collaborating with AgResearch for a new facility at the Lincoln University campus. Five TEIs are investing in a joint online campus (Tertiary Accord New Zealand).

4.41

Most of the other capital investment we saw was going into maintaining or expanding existing campus assets, or setting up new campuses in other towns and cities. We are not yet seeing the level of collaboration envisaged by the TEC in 2015/16. In our view, this represents a missed opportunity when viewed from a national perspective.

4.42

We also noted reasonably large amounts of capital spending on course development and information technology systems for student management, payroll, and financial management.

4.43

Some ITPs were experiencing cash flow challenges related to their capital investment decisions. Some of these decisions had been made when the ITPs expected student numbers to rise.

Why is this important?

4.44

Many ITPs have embarked on capital programmes to build or upgrade facilities. These are long-term, intergenerational investments that carry both opportunity and risk for an institution.

4.45

In our view, there is a need for greater scrutiny of the business cases to support investment in capital assets. The long-term affordability of capital investments, including depreciation and maintenance, will depend on accurate forecasting of future use. Although we often see a strong educational case for capital investment, councils need to ensure that the financial assumptions are subject to rigorous challenge.

9: TEIs have to pay back funding if the total dollar value of the provision that was delivered within the funding year is less than 99% of the total value.

10: Where we use the term "domestic full-time students", we are using the EFTS measure.

11: The number of first-time student visas issued does not equate to student enrolments in the same year. Most full-time students will start studying in the year after their visa is approved. Some students might defer their study or not study at all. Also, some students might take courses that are calculated to be less than one equivalent full-time student. The number of students holding a "Valid Student Visa" is higher than the number of students with first-time student visas. This is because the number of valid student visas includes people in all years of study. There were 75,578 valid student visa holders on 30 June 2017.

12: ICEF Monitor is an independent market intelligence resource for the international education industry.

13: Education New Zealand (2018), International Education Strategy 2018-2030, Wellington.

14: Whitireia Community Polytechnic and Wellington Institute of Technology operated under a combined council. A proposal to integrate the two institutes was announced on 6 November 2018.