Part 3: Financial performance of tertiary education institutions

Overall financial performance for 2017

3.1

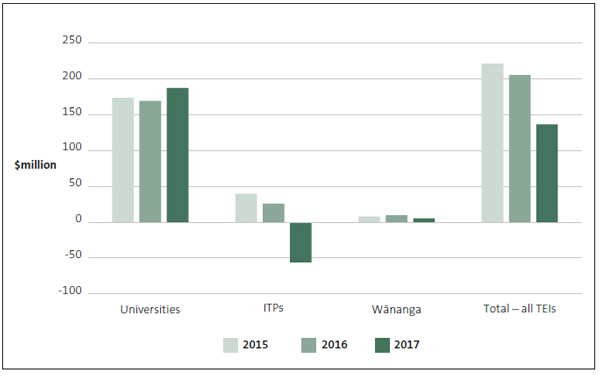

It is important that TEIs are financially stable, to support the consistent delivery of high-quality education that students can have confidence in. An operating surplus is one indicator of financial health. Figure 1 shows the aggregated surplus or deficit returned by each part of the tertiary education sector in 2017.

Figure 1

Aggregated operating surpluses and deficits for tertiary education institutions, by type, 2015 to 2017

The financial results for ITPs show a decline from a combined $26 million surplus in 2016 to a combined $56 million deficit in 2017.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General database of financial statements.

Note: The aggregated figures in Figure 1 reflect the total surpluses and deficits recorded at the TEIs' "group" level. This might include revenue and expenditure from activities other than teaching, learning, and research.

3.2

The TEC has a framework to monitor the financial viability of TEIs. One measure the TEC uses is operating surplus as a percentage of revenue. The TEC sets its low-risk threshold at 3% or above.7

Financial performance of universities and wānanga

3.3

Most of the universities are financially sound. Figure 1 shows they collectively increased their operating surpluses from $170 million in 2016 to $188 million in 2017. Two universities are in their last year of receiving Crown support8 after the Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011. These two universities are below the 3% operating surplus guideline, but the remainder are meeting or exceeding it.

3.4

The three wānanga also returned a combined surplus in 2015, 2016, and 2017. None recorded a deficit for 2017, although the combined surplus declined to $5.5 million from $9.9 million in 2016. Two wānanga did not achieve their own budgeted surplus or the TEC's operating surplus guideline.

Financial performance of the institutes of technology and polytechnics

3.5

In Figure 1, the financial results for ITPs show a decline from a combined $40 million surplus in 2015 to $26 million in 2016, and then a deficit of $56 million in 2017.

Figure 2

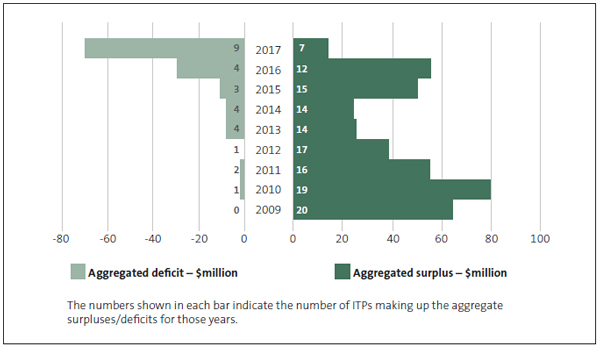

The number of institutes of technology and polytechnics in surplus or deficit, and the combined value of those surpluses and deficits, 2009 to 2017

Not all ITPs are in financial difficulty, but the combined deficit for nine of the 16 ITPs in 2017 was almost $70 million.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General database of financial statements.

Note: The number of ITPs has reduced through mergers since 2009.

3.6

Not all ITPS are in financial difficulty, but Figure 2 shows an increasing number of ITPs in deficit since 2009, with a significant increase between 2016 and 2017. Figure 2 also shows that the combined deficit is getting bigger. In 2017, nine ITPs (up from four in 2016) returned a combined deficit of almost $70 million (up from a $30 million deficit in 2016).

3.7

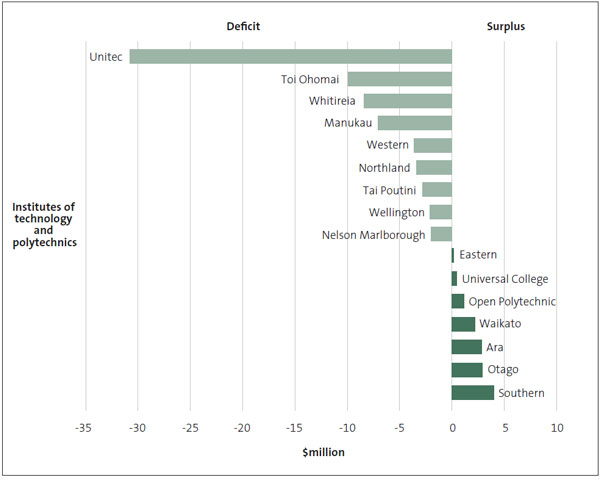

Just seven ITPs returned a surplus in 2017, and one of those was marginal. This result was down from 12 ITPs in surplus in 2016. Only two ITPs (Southern Institute of Technology and Otago Polytechnic) returned an operating surplus of 3% of revenue or more. Figure 3 shows which ITPs returned a surplus or deficit in 2017, together with the size of that surplus or deficit.

Figure 3

Institutes of technology and polytechnics in surplus or deficit in 2017

In 2017, Unitec Institute of Technology had the largest deficit and Southern Institute of Technology had the largest surplus.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General database of financial statements.

3.8

By October 2018, four ITPs were subject to intervention from the Crown because of severe financial difficulty. Others had enhanced support in place, such as Crown-appointed financial advisors.

3.9

We were concerned by the sudden deterioration in financial outlook for two of these ITPs, after the financial year-end and after we had issued our audit report. Our concerns related to the quality and timeliness of the financial forecasts provided to the ITPs' council. Our annual audits give reasonable assurance that TEIs have appropriate financial controls and systems in place to produce their financial statements. However, it is the role of council members to ensure that the chief executive and their staff use those systems to provide the good quality and timely information that council members need to oversee performance.

3.10

The TEC forecasts that most ITPs and one university will be in a deficit position by 2020. The TEC is leading a project called the ITP Roadmap 2020, to explore options for reshaping the ITP sector. The project is partly to improve the financial viability of ITPs while retaining their strong regional contribution to skills and the economy. The Minister of Education expects to report to Cabinet by the end of 2018.

3.11

As a consequence of the increasing financial pressures in the ITP sector, we expect consideration of going concern issues will feature more in our work and our reporting on the 2018 audits. In Part 4, we discuss the causes of the financial pressures in more detail, and highlight areas where councils need to remain vigilant.

7: The TEC's measures are guidelines and the TEIs are not obliged to achieve them.

8: The Crown agreed that the University of Canterbury and Lincoln University would not have to repay funding received if those universities did not achieve the funded number of student enrolments after the Canterbury earthquakes, up to and including 2018. These two universities are discussing potential partnership options.