Part 1: Why we are interested in procurement

1.1

Public organisations1 use many different kinds of goods and services to support the work of both local and central government. Procurement is the process that public organisations use to acquire these goods and services. We want New Zealanders to get the best possible outcomes from the spending of public money.

1.2

Procurement involves a range of goods, from pens and paper to major construction projects, such as schools, hospitals, and roads. Procurement also involves services provided by third parties, such as social care and health services.

1.3

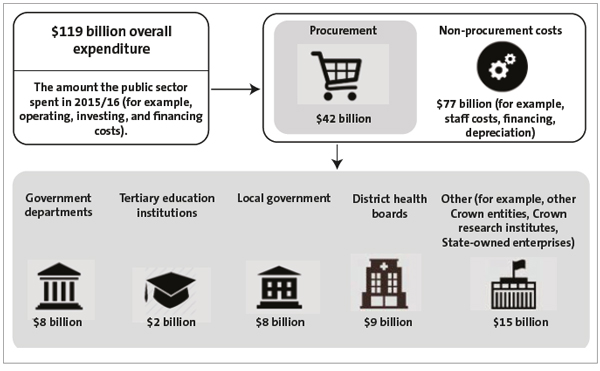

There is no easily identifiable overall number for how much the public sector spends on procurement. However, to give a sense of the significance and magnitude of the spending, we have provided an estimate. Based on 2015/16 financial statements, we estimate that the public sector spends about $42 billion annually on procurement.2 We illustrate the breakdown of this amount in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Procurement expenditure in the public sector, 2015/16

1.4

In this Part, we set out:

- what we mean by procurement;

- why we chose to focus on procurement; and

- what we hope to achieve by focusing on procurement for the next three years.

What do we mean by procurement?

Procurement is more than just buying goods and services

1.5

Procurement is more than just "buying something". For us, and for the purposes of this report, procurement includes all the processes involved in public organisations acquiring and subsequently managing goods and services from a supplier.

1.6

Procurement begins with a public organisation determining what goods and services it needs to achieve its goals. Procurement includes planning for the purchase, the purchase process itself, and any monitoring to ensure that the contract has been carried out and has achieved what it was meant to.

1.7

Procurement is complete when:

- the goods and services have been supplied and the contract or the asset's useful life is at an end; and

- the process has been reviewed to ensure that all commitments have been met, all benefits realised, and any lessons that could be learned from the procurement have been recorded.

1.8

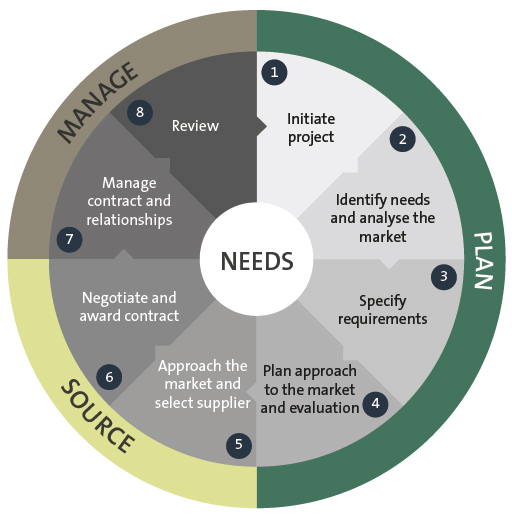

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) describes procurement as having a life cycle of eight stages (see Figure 2). This is a useful way to consider procurement. Parts 3-10 of this report discuss each stage of the life cycle.

1.9

For a procurement to be successful, it is important for a public organisation to consider each of the eight stages in the procurement life cycle. Our audit work has shown that many of the problems we see in procurement are caused by poor project initiation, poor contract management, and a failure to ensure realisation of the intended benefits. We discuss those particularly in Parts 3, 9, and 10.

Procurement and commissioning

1.10

It is important to understand the relationship between commissioning and procurement. Commissioning has become an important activity, particularly for health and social services.

Figure 2

The eight-stage life cycle of procurement

Source: (Recoloured from) the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

1.11

Commissioning starts by asking what is the best way to achieve a specific outcome. The New Zealand Productivity Commission has defined commissioning as "a set of inter-related tasks that need to be carried out to turn policy objectives into effective social services".3 These tasks can include clarifying what is needed, understanding the needs of the targeted population, and choosing how the services will be delivered.

1.12

Commissioning might lead to include procurement, but not always. For example, if the commissioning need can be met by staff, procurement will not be necessary. Procurement starts with an assumption that public organisations will be procuring goods or services from suppliers.

Procurement and grants

1.13

Grants are not usually regarded as procurement but they do involve an exchange of funding in expectation of an outcome. In our 2006 good practice guide, Principles to underpin management by public entities of funding to non-government organisations, we set out a continuum of funding arrangements that public organisations engage in, including conditional and unconditional grants.4

1.14

Regardless of what funding arrangement is used, it is essential that public organisations plan, negotiate, manage, and monitor a funding arrangement well. Public organisations must be accountable for their use of public funds. In our view, the principles in our good practice guide are as applicable to a grant as they are to a traditional contract. For that reason, some of our work on procurement will consider how well grants are managed.

1.15

Public organisations need to be accountable for the funds, and act with the integrity that is expected in any funding arrangement.

1.16

We are interested in the $1 billion annual (for three years) Provincial Growth Fund for regional economic development. The Provincial Growth Fund is designed to support non-commercial, quasi-commercial, and commercial investments. Grants will generally be used to fund non-commercial investments.

Why procurement?

Effective procurement contributes to improved outcomes

1.17

Procurement that achieves the strategic intent of the public organisation, and is managed well throughout the process, can ensure the provision of more effective and efficient public services, improving outcomes for New Zealanders.

1.18

Effective procurement can save money and ensure that more projects are delivered to time and budget, with reduced exposure to commercial risk, and less cost in doing business with government. It can lead to productivity gains and support innovation by suppliers.

Size and complexity

1.19

Suppliers play a significant role in the delivery of public services. They provide equipment, tools, and systems for government work. They also carry out government work, including complex projects, back-office administration, and public-facing services.

1.20

Some procurement is on a large scale. The 2016 Defence White Paper signalled plans to invest $20 billion in defence capabilities over the next 15 years. The Defence Capability Plan is being reviewed in 2018 and this review might result in extending the planning horizon. Another example is the range of district health board facilities that will need replacing during the next 20 years, at a likely cost of several billion dollars.

1.21

As the auditor of all New Zealand's public organisations, the Auditor-General can assess whether public organisations are carrying out their activities effectively and efficiently, as well as examine matters such as waste, integrity, legislative compliance, and financial prudence. The size and complexity of procurement means it is important that we assess how well public organisations are spending public money.

Maintaining New Zealand's international reputation for transparency

1.22

New Zealand's public sector generally has an enviable reputation when it comes to fraud and corruption. For example, New Zealand rated first on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index in 2017.

1.23

It is important not to be complacent. We continue to see cases of procurement-related fraud in the public sector. This kind of fraud is carried out mainly through using false invoices – for example, employees with delegated authority entering false or overstated invoices for payment. We continue to see the misuse of credit and fuel cards. Cyber-related fraud also continues to pose risks to public organisations.

1.24

We have also considered in recent years allegations of procurement-related corruption involving public organisations. We will continue to demand transparency in how public organisations use public funds and what they have achieved. This will help ensure that New Zealand maintains its highly regarded international reputation.

What we want to achieve

We want to improve public organisations' procurement practice

1.25

Procurement guidance, such as the Government Rules of Sourcing5 and our own 2008 good practice guide, Procurement guidance for public entities, has been available to the public sector for the last 10 years.

1.26

We have seen improvements to procurement. However, we have also identified three stages of the procurement life cycle that public organisations need to improve in: the strategic analysis, which should be done at the start of the procurement life cycle; contract management; and checking that intended benefits are realised. We have also seen:

- variability in procurement capability in public organisations;

- poor governance and management of some procurement projects;

- inconsistency in whether an effective process is followed; and

- variable quality in planning and risk management.

1.27

We want our work on procurement to improve performance in the public sector by highlighting strengths and weaknesses in procurement practice, identifying opportunities for improvement, and encouraging public organisations to take them up.

We want procurement to be carried out in a principled way

1.28

From time to time, people contact us with concerns about how a specific procurement has been carried out or conducted.

1.29

For example, they might be concerned that a procurement is in breach of legal requirements, that there has been bias or favouritism involved in selecting the supplier, or that there has been a poorly managed conflict of interest. There might also be claims of fraud.

1.30

Public organisations need to carry out their procurement in a principled way. Sometimes this is referred to as probity. Probity is a broad concept, but its principles are fundamental to how we expect public organisations to carry out procurement. These principles include:

- Transparency – Procurement processes, from developing a procurement strategy to signing a contract, should be well defined and documented.

- Fairness and impartiality – All interested suppliers should be encouraged to participate in a tender, without advantage or disadvantage. Processes should be applied lawfully and consistently, without fear or favour. Unfair advantages, including those arising from incumbent arrangements, should be identified and addressed.

- Honesty and integrity – Individuals and organisations should act appropriately and professionally. Public sector standards of conduct must be met.

- Managing conflicts of interest – Expectations about conflicts of interest and how they are managed should be clearly understood by all parties. Conflicting interests and roles, and the associated perceptions, should be identified, declared, and managed effectively.

- Confidentiality and security – Confidences should be respected and information should be held securely and safeguarded from wrongful or inadvertent disclosure.

- Accountability – There should be strong, but proportionate, project governance and reporting systems in place.

1.31

Probity is particularly important for procurement, not only because a lot of money is often involved, but because adhering to these principles is at the heart of people's trust and confidence in the public sector.

We want stronger public accountability

1.32

To help elected members and officials act in the best interests of New Zealanders, public organisations need to be accountable for their stewardship over, and use of, public funds.

1.33

It is essential that public organisations are able to demonstrate what they are doing and why. Public organisations should expect their performance to be questioned, whether by members of the public, the media, the courts, or Parliament. This is accountability in action, and public organisations need to be publicly accountable for their actions and spending.

1.34

Accountability cannot be taken for granted. By focusing on procurement, we want to make sure that all public organisations understand their obligations and responsibilities to be accountable and that the processes they follow in procurement enable them to be held to account.

We want public organisations to achieve value for money from procurement

1.35

Value for money means using resources effectively, economically, and without waste. Value for money when procuring goods or services does not necessarily mean selecting the lowest price, but rather the best possible outcome from the goods or services during their whole life.

1.36

Accordingly, we want to examine how well public organisations are conducting procurement in a way that achieves value for money and makes the most of their resources. It is important that they consider value for money at all stages of the procurement life cycle, not just at the beginning. Value for money is more likely achieved if the most appropriate procurement approach is selected.

We want to improve trust and confidence in the public sector

1.37

It is important that New Zealanders have trust and confidence in the public sector to make decisions on their behalf. It is also important that taxpayers and ratepayers have trust that public money is used appropriately, effectively, and efficiently – and not mismanaged, misused, or wasted.

1.38

Public trust and confidence in the public sector can become eroded if public organisations mismanage or misuse resources through poor procurement. By encouraging public organisations to look at all stages of the procurement process, we hope that they will strengthen their procurement practices and their stewardship of public funds.

Structure of our report

1.39

In Part 2, we provide a brief description of functional leadership roles. We then set out our proposed work looking at MBIE's and the Government Chief Digital Officer's functional leadership roles.

1.40

In Parts 3 to 10, we set out our main expectations and concerns and our planned work in the eight stages of the procurement life cycle. Each Part focuses on one of the eight stages of the procurement life cycle.

1: Public organisations include government departments, Crown entities, schools and universities, district health boards, port companies, airports, State-owned enterprises, Crown research institutes, statutory bodies, licensing trusts, local councils, and council-controlled organisations.

2: This estimate is based on the 2015/16 financial statements (group data) of local and central government organisations (2015 calendar year for TEIs). We used the "Other Operating Expenses" from the Financial Statements of the Government (excluding government transfer payments and subsidies, personnel expenses, depreciation, interest expenses, insurance expenses, grants and subsidies, rental and leasing costs, impairment). To this we added capital expenditure. We then added our estimate for local government (total expenses less fixed costs – interest, salaries and depreciation – plus capital expenditure). The total rounded to $42 billion.

3: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2015), More effective social services, page 129.

4: Conditional grants contain specified expectations to deliver certain services. Unconditional grants contain limited or no delivery expectations but are nevertheless, like conditional grants, given to achieve a public good.

5: The Government Rules of Sourcing documents are available at procurement.govt.nz.