Controller update: July to December 2024

Introduction

We have a strong interest in New Zealanders’ trust and confidence in the public sector. A key element in that is our “Controller” role, in which we check whether government spending is properly authorised and within the law.1 We carry out this role on behalf of Parliament. This update covers spending for the six months to 31 December 2024.

More generally, the Controller is interested in knowing that the system of Parliament’s control over government spending is working as intended. Appropriation scope statements (which determine what the government can spend money on) and the use of multi-year appropriations (MYAs) are two aspects the Controller is currently taking a closer look at.2

Key points

- The 2024/25 Budget allowed spending of up to $182.2 billion, with an additional $29 billion authorised under the second Imprest Supply Act.

- With one notable exception, government spending for the first six months of 2024/25 was properly authorised and within the law.

- The single confirmed instance of unappropriated expenditure results from an estimated $3.2 billion increase in the Crown liability for veterans’ support.

- We have looked at whether Parliament has clarity about the scope of spending that the Government seeks authority for and seen scope statements that we consider inadequate. Because of this, we will carry out a more comprehensive review during 2025.

Our role

The Controller and Auditor-General is often referred to as the public “watchdog” on government spending. An important part of the watchdog role is the Controller function.

In this Controller role, we provide assurance to Parliament and the public that the Government has spent public money in line with the authority provided by Parliament. If money is spent without authority, then we ensure that it is accurately reported in the Financial Statements of the Government and the relevant government department’s annual report.

The Auditor-General carries out the Controller role throughout the year and reports more fully to Parliament and the public after the end of the financial year to 30 June.3

Unappropriated expenditure between July and December 2024

We have confirmed one instance of unappropriated expenditure that occurred between 1 July and 31 December 2024.

On 20 October 2024, the Veterans’ Entitlements Appeal Board reached a decision that has significant implications for the assessment and valuation of veterans’ support entitlements.4 The specific decision related to a claim that a veteran’s illness had been caused by exposure to Agent Orange, and it will affect future claims by broadening veterans’ access to entitlements.

The likely cost has been assessed as $3.2 billion and the Crown’s liability for Veterans’ Support Entitlement has increased by that amount.

The amount appears in the Service Cost – Veterans’ Entitlements non-departmental appropriation within Vote Defence Force. Only $12 million had been authorised for these costs in Budget 2024 – the effect of the Appeal Board’s ruling was not anticipated. The between-Budget increase has therefore resulted in unappropriated expenditure of nearly $3.2 billion, the largest single instance of unappropriated expenditure we have identified to date.

The Treasury disclosed the estimated increase in the Veterans’ disability entitlement liability in its latest Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU). The Update showed an expense of $3.2 billion for the net revaluation of veterans’ disability entitlements, which incorporates the adjustment for the Appeal Board’s decision.5 The Treasury states that, given the high level of uncertainty about the effects of the decision, there is a risk the actual fiscal impact will differ from the amounts assumed in the fiscal forecasts.6 A $3.2 billion revaluation of the veterans’ disability entitlements was reported in the (unaudited) November 2024 interim Financial Statements of the Government.7

Although the New Zealand Defence Force is updating and implementing new procedures to reflect High Court guidance and the Appeal Board’s decision, it is appealing the decision to seek clarification about how the Veterans’ Support Act 2014 should be interpreted.8

As part of our Controller function, our auditors will monitor any adjustments to the liability to determine whether any future increases are within appropriation.

Current areas of focus

Parliament controls government spending by ensuring that there are limits attached to the appropriations it authorises.9 Two of those limits are:

- the scope of permitted expenditure (that is, what public money can be spent on); and

- the time period for which the expenditure is authorised (that is, when public money can be spent).10

The Controller is interested in whether the system of Parliamentary control over public spending is working as intended. Currently, we are looking particularly at how well public spending is controlled by defining what it is spent on (that is, the scope). We are also looking at when it can be spent by considering the use of flexible time periods under multi-year appropriations (MYAs).

The scope of appropriations (what public money can be spent on)

The appropriation “scope statement” is a critical part of how Parliament controls government spending. It determines what public money can and cannot be spent on and sets a legal boundary. For example, if a scope statement limits an appropriation to be used for flood protection, it cannot then be used for drought relief.

The scope statement is designed to set boundaries that prevent unauthorised spending while not being so narrow that it constrains the spending the appropriation is intended to authorise. Given its importance in controlling public spending, the scope statement wording must be clear and unambiguous. It needs to be specific enough to be verifiable so that the Controller can determine, on behalf of Parliament, whether expenditure is within or outside the scope of the appropriation.11

There were more than 700 appropriations for authorising government spending included in Budget 2024. From an initial look at the scope statements of a sample of Votes, we found several examples that we consider problematic.

Vague statements

Some of the scope statements are vague and do not identify the services that are to be supplied. For example:

- “This category is limited to the delivery of services to support New Zealand individuals, businesses and agencies overseas ”. The approved spending is for $62.1 million.

- “This appropriation is limited to provision of support services to other agencies.” The approved spending is for $11.3 million.

In our view, scope statements for service-related appropriations12 should limit expenditure to a particular class of services and clearly identify what those services are. From the above scope statements, it is not clear what sort of services Parliament is being asked to authorise spending on.

We also consider that the scope statements below do not provide enough information about what the expenditure is to be used for:

- “This category is limited to initiatives that support digital technologies sector initiatives.” The approved spending is for $569,000.

- “This appropriation is limited to the provision of services, resources, assistance and support to people so they can participate in and contribute to the wider community.” The approved spending is for $116.2 million.

Catch-all statements

Scope statements are supposed to clearly define and thereby constrain what public money is spent on. The following appropriation appears to permit spending on any services that have not already been specifically authorised:

- “This appropriation is limited to the provision of services by [the department] to … other agencies where those services are not within the scope of another departmental output expense appropriation in [Vote].”

We have so far seen this sort of wording in three separate Votes (combined approved spending of $23.5 million).

In our view, the spend-on-anything-else-that-isn’t-already-specified statement defeats the objective of achieving control over what public money can be applied to.

Overlapping scope

To effectively control expenditure, scope statements need to be mutually exclusive, otherwise a limit on spending under one appropriation can be circumvented by using another. We have identified wording of scope statements for different appropriations that is too similar, to the extent that the scopes are not mutually exclusive.

For example, in one Vote we found two separate multi-year appropriations with the following scope statements:

- “This appropriation is limited to funding for private businesses to undertake research and development and capacity building activity.” The approved spending is for $116 million.

- “This appropriation is limited to funding for private businesses to undertake research and development activity.” The approved spending is for $7.5 million.

Those two appropriations have different titles, which indicate that the grant funding has different purposes. However, titles do not form part of the legal criteria for appropriations; the legal specification about what the grant funding can be used for is almost identical in the two appropriations. As such, public funds for “private businesses to undertake research and development” have been authorised through two separate appropriations.

Next steps

We will carry out a more comprehensive review of scope statements during 2025. We will also pay close attention to the suitability of scope statements in our annual audits and in our advice to select committees during this year’s review of the Budget Estimates.

We will discuss any identified problem areas with the relevant government departments and will highlight any general concerns to the Treasury.

We acknowledge that there is not sufficient time for government departments to amend their scope statements for Budget 2025, but we urge departments to rectify deficient scope statements in time for Budget 2026.

Multi-year appropriations

In May 2024, we reported on the increasing use of multi-year appropriations (MYAs).13 MYAs provide more flexibility than standard appropriations because one of the means of control – the specified time period – is longer than one year. This means that the authorised spending can take place any time within the multi-year period.

MYAs should be authorised only when justified, in line with the Treasury’s criteria. We noted that the number of MYAs has increased significantly over recent years. In our report, we said that we considered it timely for government departments and the Treasury, as part of their Budget process, to review the use of MYAs and confirm that this mechanism for providing flexibility in public spending is being used appropriately.

The Treasury had been piloting the use of a very flexible appropriation structure, multi-year, multi-category appropriations (MYMCAs). In early 2024, the Treasury reviewed the use of MYMCAs and decided to discontinue their use because of lack of evidence of their benefits.

MYAs have nearly trebled in use in recent years (about 19% of all appropriations are MYAs). The Treasury tells us that there will be no change to current practice for Budget 2025 (other than the discontinuance of MYMCAs). However, it has said that its longer-term work programme includes reviewing the rules for using MYAs to strengthen fiscal discipline. We encourage moves to strengthen fiscal discipline, including reviewing how MYAs are used to achieve that.

However, the primary function of appropriations (in their various forms) is to allow Parliament to control the public purse (that is, to control the spending of taxpayer funds). When contemplating the use of various appropriation structures, our view is that a primary consideration is whether there is enough justification for departing from the normal means of Parliamentary control – the standard, annual appropriation.

We will continue to monitor the use of MYAs and look forward to the results of the Treasury’s review of the rules for using them.

How was government expenditure authorised for 2024/25?

A central feature of New Zealand’s parliamentary democracy is the requirement that all government expenditure be authorised by Parliament. Parliament authorises most Crown spending through the annual Act that gives effect to the Government’s Budget – the annual Appropriation (Estimates) Act.

However, the Appropriation (Estimates) Act is typically passed two or three months into the financial year – the current Act did not come into effect until 1 October 2024.14

- To authorise government spending from 1 July to 30 September 2024, Parliament enacted the first Imprest Supply Act for the year.15

- To authorise the annual Budget, Parliament enacted the main Appropriation (Estimates) Act (effective from 1 October 2024).16

- To allow for spending from 1 October 2024 that is not included in the Budget, Parliament enacted a second Imprest Supply Act for the year.17

The first Imprest Supply Act

Because the Act authorising the Budget 2024 spending would not be enacted until well into the financial year, Parliament provided “interim authority” to the Government through the first Imprest Supply Act. This is normal and it happens every year.

The first Imprest Supply Act allowed the Government to spend money from the start of the financial year until the Budget was passed. Imprest Supply Acts are typically not prescriptive. The first Act for 2024/25 allowed the Government to incur expenses of up to $34 billion, to incur capital expenditure of up to $6 billion, and to make capital injections18 of up to $1 billion.

These figures are generally based on a proportion of the annual Budget, and the main purpose of the Act is to allow the Government to spend in line with its Budget before receiving “appropriation” for that spending through the subsequent Appropriation (Estimates) Act.

Our Controller work for 2024/25 began in October, when we received financial information on government spending from the Treasury. When checking that information, we determined that Government expenditure had remained within the limits authorised under the first Imprest Supply Act.

The main Appropriation Act

The legislation that enacted the Government’s 2024/25 Budget came into force 1 October 2024. This Act authorises most of the spending included in the Government’s Budget in the form of annual appropriations.19 The total budgeted spending for all appropriations in Budget 2024 was $182.2 billion.20

Each month from October to June, the Treasury is required to report to the Auditor-General (in his capacity as Controller) the amount of spending authorised under each appropriation and the amount of spending incurred for each appropriation to date.21

We use the information that the Treasury provides to monitor government spending throughout the year. We examine the information for any issues arising and determine whether public spending remains within the limits that Parliament authorised.

The second Imprest Supply Act

The changing nature of government activities and unexpected demands mean that it is rarely possible to foresee all future expenses and capital expenditure for the year. For this reason, Parliament provided the Government with additional spending authority through the second Imprest Supply Act for 2024/25. This Act authorises spending additional to that in the main Appropriation Act from 1 October 2024 to 30 June 2025. This is also normal and happens every year.

The second Imprest Supply Act gives the Government room to respond to any changes since it put the Budget together by allowing for spending that it might not have envisaged at that time. It provides the Government with some (limited) flexibility to reprioritise its spending during the year as circumstances change.22

As with the first Imprest Supply Act, the second Act is not prescriptive. The second Act for 2024/25 allows the Government to incur expenses of up to $16 billion, to incur capital expenditure of up to $12 billion, and to make capital injections of up to $1 billion, in addition to that authorised under the main Appropriation Act (an additional 16%).

Parliament expects the Government to carefully control the use of the authority it provides to incur spending not included in the initial Budget (that is, changes to levels of current authorities and any new spending). The Government does this by applying Cabinet rules.

A specific Cabinet decision must be made before the Government can access the extra spending authority available through imprest supply.23 Cabinet decisions approve the use of imprest supply for each particular purpose and set the period, amount, type, and scope parameters for the spending.

As such, Cabinet approvals to use imprest supply place the same parameters on spending as the appropriations. These decisions are ultimately reflected in the appropriations when Parliament authorises the Government’s updated Budget later in the financial year.24

In this way, Cabinet controls how and when government departments can use the spending authority provided under the second Imprest Supply Act.

An important part of our Controller work is checking that decisions to use the second Imprest Supply Act have been made according to the rules. Each month, we check a sample of Cabinet and joint Ministers’ decisions to confirm that they have been properly authorised. We then check that changes affecting appropriations have been correctly recorded in the Government’s financial information system.

From that point, spending incurred under imprest supply must remain within the parameters that those Cabinet decisions set, and we monitor this as well.

Each month, we check that total spending under this Act (that is, the amount of between-Budget spending decisions) has not exceeded the legislated limits for expenses ($16 billion), capital expenditure ($12 billion), or capital injections ($1 billion). As at 30 December 2024, Cabinet’s new spending decisions were well within those limits.

How does 2024/25 compare with recent years?

As we mentioned above, Parliament authorised $41 billion through the first Imprest Supply Act for the year. This acted as a “stop gap” measure to allow the Government to operate until its Budget passed. This amount is in advance of, but does not add to, the Budget.

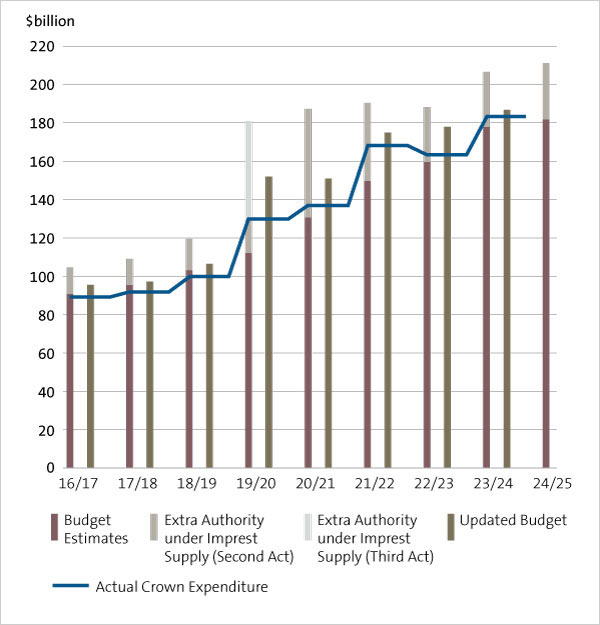

Figure 1 shows the Government’s initial budget,25 the updated Budget,26 and actual public spending for the last nine years.27 The initial spending authority that Parliament provided to the Government each year28 has more than doubled during the last nine years, from $104 billion to $211 billion.

Figure 1:

The Government’s budgeted, authorised, and actual expenditure from 2016/17 to 2024/25, in $ billions

Actual expenditure (represented by the line in Figure 1) is tracking at a similar rate.29 Although actual spending has never exceeded the total authority available, there have been many instances of spending exceeding individual appropriation limits.

We will report again later in 2025 on the full year’s work of the Controller function.

1: We sometimes use the term government “spending” and public “spending” for readability reasons. It refers to public expenditure incurred by the Crown (in this context, the Crown means Ministers and their departments).

2: An “appropriation” is a parliamentary authorisation for the Crown or an Office of Parliament to incur expenses or capital expenditure.

3: See, for example, Part 2 of Our audit of the Government’s financial statements and our Controller function

4: Veterans' Entitlements Appeal Board - Decision following re-hearing, October 2024.

5: The Treasury, Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update 2024, 17 December 2024, page 108

6: The Treasury, Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update 2024, 17 December 2024, page 78.

7: Interim Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the five months ended 30 November 2024 (23 January 2025), page 9.

9: Those “limits” constitute the properties of the appropriation, which are sometimes referred to as the dimensions of appropriations.

10: The other limits are the maximum dollar amount and the expenditure type.

11: The Treasury sets out the requirements for scope statements in its publication, A Guide to Appropriations. It requires that output class appropriations (which make up $49 billion in the latest Budget) convey a meaningful understanding of the outputs within the output class.

12: These are classified in the Vote Estimates as output expenses.

13: See The increasing use of multi-year appropriations at oag.parliament.nz.

14: The Appropriation (2024/25 Estimates) Act 2024.

15: The Imprest Supply (First for 2024/25) Act 2024 was enacted on 29 June 2024.

16: The Appropriation (2024/25 Estimates) Act 2024 was enacted on 30 September 2024 and authorises spending from 1 October 2024 to 30 June 2025. (It also authorises some spending for multi-year periods.)

17: The Imprest Supply (Second for 2024/25) Act 2024 was enacted on 30 September 2024 and provides interim authority for spending from 1 October 2024 to 30 June 2025. All spending authorised under this interim authority must be “appropriated” through an Appropriation Act by 30 June 2025. The Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Act is the usual place for appropriating this spending.

18: A capital injection is a transfer of resources from the Crown to a government department, which increases the size of its departmental balance sheet. It represents an increase in the equity of the department and is generally provided to acquire assets for use in providing the department’s services.

19: The Budget also includes spending authorised by other legislation.

20: This figure includes capital injections as well as forecast expenditure for permanent and multi-year appropriations.

21: Section 65Y of the Public Finance Act 1989.

22: All governments move funding around during the year. This is done within defined limits and according to strict rules.

23: Some decisions may be made jointly by the appropriation Minister and the Minister of Finance (“joint Ministers”) by prior approval of Cabinet.

24: That is, through the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Act.

25: The initial budget refers to the main Budget Estimates, as presented on Budget Day, and included in the annual Appropriation (Estimates) Acts.

26: The updated budget refers to that reflected in the Supplementary Estimates, which includes changes to spending levels and any new areas of spending since the initial budget.

27: Actual Crown expenditure is the total amount of spending incurred under each Vote. It includes inter-departmental transfers. These figures will therefore not reconcile with the consolidated Financial Statements of the Government.

28: That is, through the initial Budget Estimates and the second and third Imprest Supply Acts. (The use of a third Imprest Supply Act is rare. At the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2019/20, Parliament granted the Government additional spending authority through a third Imprest Supply Act to ensure that the Government could lawfully spend what it needed to on the pandemic response.)

29: Nominal dollars are not adjusted for inflation and do not indicate the per capita spend.