The increasing use of multi-year appropriations

Overview

In New Zealand, the Government (that is, Ministers and government departments) can’t spend taxpayer money without Parliament’s approval. That’s an important part of how our democracy works – Parliament,1 as the representative of the people, controls what the Government can and cannot do, including what it can and cannot spend money on.

In New Zealand, the Government (that is, Ministers and government departments) can’t spend taxpayer money without Parliament’s approval. That’s an important part of how our democracy works – Parliament,1 as the representative of the people, controls what the Government can and cannot do, including what it can and cannot spend money on.

Parliament controls Government spending mainly by passing the annual Budget into law.2 Parliament approves most Government spending in the Budget through annual appropriations.3 Each appropriation is an individual legal authority that allows the Government to spend public money. The money is used for a wide range of things, such as pest control on conservation land, search and rescue services, funding schools and public hospitals, paying social welfare benefits, and providing policy advice to Government Ministers.

Annual appropriations are provided each year and cover spending for one year at a time. This allows Parliament to closely control the spending of public money.

However, the Government can also ask Parliament to approve spending through multi-year appropriations (MYAs). Instead of covering spending for one year at a time, MYAs can cover spending over up to five years.

The law allows for the use of MYAs because there can be good reasons for giving Government more flexibility over how much money to spend in which year, over a limited number of years. This can be particularly useful for spending on a specific project when there is uncertainty about the pattern of spending (that is, how much spending is likely to occur in which year). Examples include the funding of specific environmental clean-up and climate emergency responses, large construction projects such as new hospitals, and complex investigations such as Royal Commissions.

By their nature, MYAs are a looser form of control over public spending compared with annual appropriations. It’s a bit like changing how you might manage your grocery budget – instead of allocating a fixed amount for each week, you allocate a much larger amount for each month. This gives you more freedom to choose how much you spend and when, according to your needs.

The Treasury has set out guidelines for the use of MYAs and states that they should be used sparingly and not when an annual appropriation should be used.

We have seen a significant increase in the use of MYAs. They have risen from 7% to 19% of all appropriations over the last eight years and cover many billions of dollars of Government spending.

There has also been a large increase in the number of MYAs established between Budgets, and these are not typically subject to the same level of scrutiny by Parliament as those included in the Budget are.

The increase in MYAs risks lessening the level of Parliamentary control and scrutiny over the Government’s spending plans. We have also seen examples of MYAs being used for the sorts of spending we’d expect to be covered by annual appropriations. For these reasons, we believe it is timely for government departments and the Treasury to review their use and consider whether the current MYAs are all justified.

Background

Under New Zealand’s constitutional and legal system, the Government must obtain Parliament’s approval to spend public money.4 Parliament authorises that spending through legislation, mainly by passing the annual Budget into law.5 That legislation (in the form of Appropriation Acts) includes specific spending authorities known as appropriations.

Parliament controls the spending by placing boundaries around appropriations. As such, Government spending is typically limited in terms of its amount, period, type, and scope.

Most public spending is authorised annually, in the form of annual appropriations. The Government prepares its Budget each year, together with an annual Appropriation Bill that seeks authority to incur spending on specific items for that financial year. Authorising public spending year by year is a key factor in Parliament’s control of the Government’s financial resources.

Appropriation Acts can also authorise multi-year appropriations (MYAs). Spending under each MYA is not authorised annually; it is authorised once to cover spending that can be incurred across several years. The use of MYAs is increasing and making up an increasingly large proportion of the Budget.6

What are multi-year appropriations?

MYAs are, as the name suggests, appropriations that span more than one year.

Appropriations usually lapse at the end of each financial year. However, the Public Finance Act 1989 enables appropriations that authorise spending over more than one financial year to be included in an Appropriation Act, so long as the period is for no more than five financial years.7

MYAs are designed to give government departments flexibility in spending without needing to seek authority each year. The total amount authorised through the MYA can be spent at any time during the period of the appropriation. It could be evenly spent across the years or during only a few, as required.

Any amount can be spent in any year so long as the total amount of the MYA is not exceeded. These types of appropriation are particularly useful when spending is unpredictable (for example, when natural disasters or pandemics occur).

How are multi-year appropriations authorised?

MYAs are authorised in the same way as annual appropriations, through Appropriation Acts. The entire amount for the whole period of the MYA is authorised in the one Act. New MYAs created as part of the annual Budget process are included in the following Appropriation (Estimates) Act. After this, the legal authority to spend continues for the period of the MYA.

An MYA can also be set up between Budgets. For these, Cabinet needs to approve the use of imprest supply8 for any spending incurred during the current financial year, in advance of Parliament authorising the MYA through the following Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Act. The entire amount for the MYA will be authorised in the one Supplementary Estimates Act. MYAs are specified in the Appropriation Act and appear in their own table in the respective Vote.9

What is the purpose of multi-year appropriations?

MYAs first appeared in the 1994/95 financial year. An MYA was established to provide for the settlement of claims under the Treaty of Waitangi over the following five years. It was subsequently extended by a further year.10

The Treasury’s guidance states that MYAs are intended for:

- specific, time-bound (not ongoing) activities;

- where total costs are well defined; and

- where the timing of the spending between years is uncertain.11

Given this, the Treasury states that MYAs should be used sparingly and not for convenience if an annual appropriation would be sufficient or more appropriate.

This suggests that MYAs are designed for more discrete initiatives of limited time duration, where the years in which the spending falls might not be easily predicted.

MYAs provide Ministers and their departments with greater flexibility in the timing of incurring spending, up to the total amount of the appropriation. MYAs also reduce the administration that would otherwise be required to seek authority each year for unpredictable spending.

More flexibility but less control

Parliament authorises spending through MYAs in the same way as for annual appropriations. However, MYAs by their nature reduce Parliament’s control of the public purse in the sense that several years of spending are authorised at once, rather than authorising each year for one year at a time. In our view, any device that loosens Parliament’s control of the public purse should be used carefully.

Multi-year appropriations set up between Budgets

For MYAs created between the main Budgets, Cabinet approves the full amount of the MYA against the current year’s Imprest Supply Act. It is therefore possible that the amount authorised for large MYAs can exceed the amount of imprest supply remaining for the year. This is permissible, so long as the actual spending incurred under that authority does not cause the imprest supply limits to be breached.

ExampleA five-year MYA, Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities Crown Lending Facility, was established under Vote Housing and Urban Development between Budget 2022 and Budget 2023. The amount of authority sought for the MYA was $12.7 billion. In approving the use of imprest supply for the MYA, Cabinet allocated the full $12.7 billion against the Imprest Supply Act for 2022/23.12 This follows the normal process for using imprest supply, but the total authority for the MYA alone exceeded the Imprest Supply Act’s capital expenditure limit of $11.5 billion. Importantly, the actual amount incurred remained within the Act’s limits. |

Although it is unlikely that government departments will heavily “front load” spending under MYAs, there remains a potential risk that spending could breach the Imprest Supply Act. As part of our Controller work, we carry out additional checks to provide assurance that spending has remained within the Imprest Supply Act limits.

Another aspect of MYAs established between Budgets is less opportunity for scrutiny. MYAs established between Budgets receive scrutiny as part of the Supplementary Estimates examination, not as part of the standard select committee examination of the main Estimates.13 The Supplementary Estimates examination is usually a short hearing covering multiple Votes.

Between-Budget MYAs mean that spending for several years into the future can be approved without in-depth Parliamentary scrutiny.

Example (continued)The $12.7 billion Vote Housing and Urban Development MYA was appropriated through the Supplementary Estimates Act that was passed in late June 2023.14The supporting information for the appropriation lacks any performance criteria about what the Government intends to achieve with this lending facility. Only one performance measure was provided, which was: “Payments are made in accordance with the terms of the agreement for notified claims”. This relates to internal, administrative activity and, in our view, is not a sufficient performance measure for Parliament to hold the Government to account for its use of the money or the outcomes it has achieved. In examining the Supplementary Estimates on 31 May 2023, the select committee hearing devoted less than three minutes to scrutinising the new $12.7 billion appropriation,15 and one written question on the appropriation was later put to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.16 |

Parliament’s control of the public purse rests not only on its power to pass legislation to authorise spending but also on its opportunity to adequately examine the Government’s spending proposals before passing the legislation. We consider it preferable to avoid asking Parliament to authorise large amounts of spending covering several years between Budgets, when there is less opportunity for in-depth scrutiny of the spending and the performance criteria by which the Government proposes to hold itself accountable.

The Treasury states in its technical guidance to government departments that, “MYAs are, by their nature, difficult to monitor and report and so are less transparent for accountability purposes than annual appropriations”.17 Therefore it is important that there are sufficient controls over establishing and monitoring MYAs.

Increased use of multi-year appropriations

Since their introduction in 1994/95, MYA use has increased. By Budget 2008 there were 20 MYAs,18 increasing to 59 in 2015/16, and increasing significantly since then, to 167 in 2022/23 (see Figure 1).19

Figure 1: Number of multi-year appropriations, 2015/16 to 2022/23

Figure 1 shows the split between “departmental” and “non-departmental” MYAs. Departmental appropriations authorise spending by government departments or Officers of Parliament. Non-departmental appropriations authorise spending by other parties, on behalf of the Crown,20 such as services purchased from Crown entities and non-government organisations, and benefits and other payments made to third parties. Figure 1 shows that 145 of the 167 MYAs (87%) are non-departmental appropriations, while 22 (13%) are departmental.

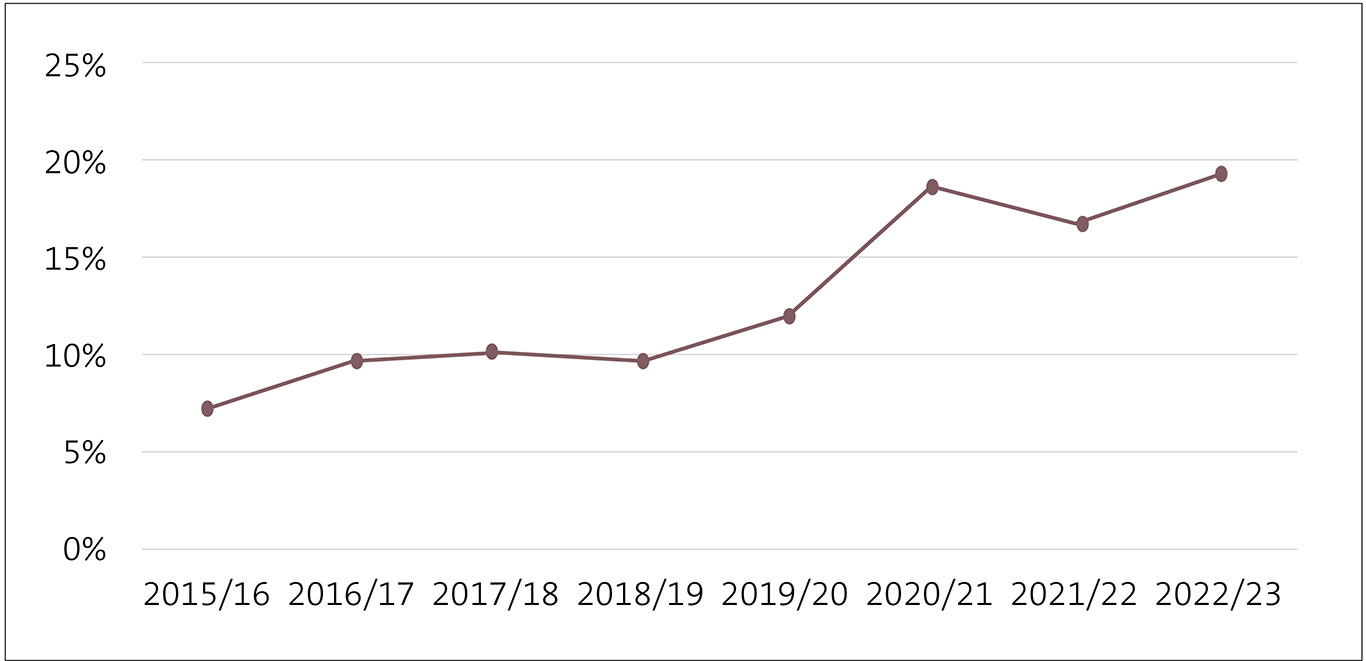

Over the last eight years, the number of MYAs as a percentage of the total number of appropriations increased from 7% to 19% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of multi-year appropriations as a percentage of total appropriations, 2015/16 to 2022/23

As at Budget 2023, about $44 billion of public spending was authorised through MYAs, compared to $133 billion through annual appropriations.21 However, the two figures are not directly comparable because the MYA figure covers spending intended to be incurred over several financial years.

There has also been a large increase in the number of MYAs set up between Budgets (that is, outside the main annual Budgets) – about four to five times as many in the last five years compared with the previous five years.

The number of MYAs differs considerably across Votes and between departmental and non-departmental (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Votes with many multi-year appropriations in place, 2022/23

| Vote | Departmental | Non-departmental | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business, Science and Innovation | 3 | 35 | 38 |

| Transport | 1 | 27 | 28 |

| Housing and Urban Development | 0 | 22 | 22 |

| Finance | 1 | 13 | 14 |

| Parliamentary Service | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Other22 | 17 | 39 | 56 |

| Total | 22 | 145 | 167 |

MYAs are not usually used for departmental spending because most day-to-day departmental spending is best managed through annual appropriations. Figure 4 identifies those Votes that do include departmental MYAs, along with the number of departmental MYAs within those Votes.

Figure 4: Departmental multi-year appropriations, 2022/23

| Number of MYAs | Votes |

|---|---|

| 1 | Finance, Labour Market, Lands, Office of the Clerk, Pacific Peoples, Statistics, Te Arawhiti, Transport |

| 2 | Customs |

| 3 | Arts, Culture and Heritage; Business, Science and Innovation; Internal Affairs; Social Development |

We have noted three departmental MYAs that authorise spending on policy, financial, and ministerial advice.23 In our view, this sort of activity does not appear to fit with the purpose of MYAs, as set out in the Treasury guidance we referred to earlier.

Summary

The Public Finance Act 1989 provides the ability for Parliament to make appropriations for more than one year, through MYAs. According to Treasury guidance, MYAs are intended for time-bound activities where total costs are well defined and the timing of spending is uncertain. They are useful in providing the Government with flexibility on spending, but they do have some downsides.

The number of MYAs has increased significantly over the last eight years.

We would expect that the increase in the use of MYAs would be a reflection of, and appropriate to, activities in the Government’s work programme.

We note the Treasury’s caution that MYAs should be used sparingly and not as a convenient substitute when using annual appropriations would be more appropriate. We have not examined the 167 MYAs to determine which activities they cover or why their number has increased so much in recent years. However, we note examples where MYAs authorise spending on policy advice and other activities that we would expect to be covered by annual appropriations.

In our view, decisions to use MYAs should not be made lightly, and MYAs should be authorised only when justified. We consider it timely for government departments and the Treasury, as part of their Budget process, to review the use of MYAs and confirm that this mechanism for providing flexibility in public spending is being used appropriately.

1: More specifically, the House of Representatives.

2: We sometimes use the term “Government spending” to refer to public expenditure (that is, expenditure incurred by government departments and their Ministers).

3: An appropriation is a Parliamentary authorisation for the Government or an Office of Parliament to incur expenses or capital expenditure.

4: Section 22 of the Constitution Act 1986.

5: Section 4 of the Public Finance Act 1989. Authority for some expenditure is set in legislation – “permanent legislative authority” (PLA). PLAs are often used when Parliament wishes to signal a commitment to not interfere in certain transactions, such as salaries of the judiciary. Imprest Supply Acts provide interim legislative authority in advance of Appropriation Acts.

6: For the purposes of our analysis, “Budget” here refers to the Government’s final budgeted amount, as updated in the Supplementary Estimates.

7: Section 10(3) of the Public Finance Act 1989.

8: Imprest supply is an interim, legal authority provided through an Imprest Supply Act that allows the Government to incur expenditure ahead it being appropriated (that is, in advance of it being authorised through an Appropriation Act).

9: A Vote is a grouping of one or more appropriations that are the responsibility of a Minister of the Crown and are administered by a department. Votes generally take the name of the portfolio of the Vote Minister.

10: Wilson, D (2023), McGee Parliamentary Practice in New Zealand, 5th Ed., page 549.

11: The Treasury (2023), Annex C : Financial Recommendations for Multi-year Appropriations, in Writing Financial Recommendations for Cabinet and Joint Minister Papers: Technical Guide for Departments, page 52.

12: The Imprest Supply (Second for 2022/23) Act 2022.

13: See our discussion on Parliament’s scrutiny of the Supplementary Estimates: “Controller update: What do you know about Supplementary Estimates?”, at oag.parliament.nz.

14: Appropriation (2022/23 Supplementary Estimates) Act 2023.

15: Finance and Expenditure Committee (May 2023), Supplementary Estimates of Appropriations for the year ended 2023.

16: Finance and Expenditure Committee (June 2023), The Supplementary Estimates of Appropriations for the year ending 30 June 2023, at treasury.govt.nz

17: The Treasury (2023), Annex C : Financial Recommendations for Multi-year Appropriations, in Writing Financial Recommendations for Cabinet and Joint Minister Papers: Technical Guide for Departments, page 52.

18: Harris, M, and Wilson, D (2017), McGee Parliamentary Practice in New Zealand, 4th Ed., page 528.

19: This number includes all MYAs with an expiration date after 30 June 2022. It includes MYAs with no remaining spending authority.

20: “The Crown” refers to Government Ministers and their departments. Government departments are responsible for administering non- departmental appropriations within their respective Votes.

21: This excludes forecast expenditure for permanent legislative authority (PLAs) and revenue dependent appropriations (RDAs).

22: Other includes the remaining 41 Votes.

23: These are multi-category MYAs, known as MYMCAs, and are within Vote Arts, Culture and Heritage; Vote Finance; and Vote Pacific Peoples. MYMCAs are currently being trialled to provide departments with even greater flexibility to manage expenditure, and the Treasury is reviewing their use.