Part 2: The Controller function

2.1

The Controller function is an important part of the Auditor-General’s work. It supports the fundamental principle of Parliament’s control over government expenditure.

2.2

Under New Zealand’s constitutional and legal system, the government needs Parliament’s approval to:

- make laws;

- impose taxes on people to raise public funds;

- borrow money; and

- spend public money.18

2.3

Parliament’s approval to incur expenditure is mainly provided through appropriations,19 which are authorised in advance through the annual Budget process and annual Acts of Parliament.

2.4

Most government expenditure is authorised through the annual Appropriation (Estimates) Acts. Parliament provides additional authority through annual Imprest Supply Acts and through permanent legislation. (See Appendix 2 for an explanation of how Parliament authorises government expenditure.)

2.5

The incidence of unappropriated expenditure reached a historical low in 2020/21, with 12 instances. Since then, the number of instances has risen to 21 in 2023/24. The amount of unappropriated expenditure as a percentage of the Government’s budget was 0.62% of the budgeted spend (2022/23: 0.20%).20

2.6

In this Part, we discuss:

- why the Controller work is important;

- how much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2023/24 and why;

- how 2023/24 compares with previous years;

- the reasons for unappropriated expenditure during the last nine years; and

- a summary of work we carried out in 2023/24 to discharge the Controller function.

Why the Controller work is important

2.7

Appropriations enable Parliament, on the public’s behalf, to have adequate control over how the government plans to spend public money.21 They also mean that the government can subsequently be held to account for how it used that money.

2.8

Most of the Government’s funding is obtained through taxes. Parliament and the public are entitled to assurance that the government is spending public money as authorised by Parliament.22

2.9

As the Controller, the Auditor-General helps maintain the transparency and legitimacy of the public finance system. The Auditor-General provides an important check on the system, on Parliament’s and the public’s behalf, by providing independent assurance that the spending is within authority.

2.10

The Auditor-General also provides assurance that any government spending without authority has been identified and dealt with appropriately.

2.11

In Appendix 2, we explain how public expenditure is authorised, who is responsible for managing it, and the Controller’s role in checking it.

How much public expenditure incurred in 2023/24 was unappropriated?

2.12

The Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2024 report 21 instances of unappropriated expenditure (2022/23: 19 instances ). Expenditure incurred above or beyond appropriation for 2023/24 was $1.17 billion (2022/23: $349.251 million). Figure 2 shows a breakdown of unappropriated expenditure categories.23

Figure 2

Unappropriated expenditure incurred for the year ended 30 June 2024

| Category | Unappropriated expenditure by category | 2023/24 Number |

2023/24 $million* |

2023/24 Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act 1989 | 2 | 17 | Education |

| B | Expense or capital expenditure incurred without appropriation or other authority | 7 | 496 | Arts, Culture and Heritage; Finance; Justice; Revenue; Social Development; Transport |

| C | Expense or capital expenditure incurred in excess of appropriation or other authority | 10 | 641 | Business, Science and Innovation; Customs; Education; Health; Revenue; Te Arawhiti; Transport |

| Category | Unauthorised capital injections | 2023/24 Number |

2023/24 $million* |

2023/24 Votes |

| D | Capital injection made without authority or approval under section 25A of the Public Finance Act | 1 | 3 | Ombudsmen |

| E | Capital injection made in excess of authority or approval under section 25A of the Public Finance Act | 1 | 13 | Business, Science and Innovation |

| Total | 21 | 1,170 |

* Amounts are affected by rounding.

2.13

The unappropriated expenditure categories shown in Figure 2 fall into the following three broader categories:

- Approved by the Minister of Finance (Category A): Under section 26B of the Public Finance Act 1989, the Minister of Finance may approve small over-runs of expenditure (that is, within $10,000 or 2% of the appropriation) if it takes place in the last three months of the financial year. Although unappropriated, expenditure approved under section 26B is lawful. There were two instances of unappropriated expenditure authorised under this section for 2023/24.

- Without appropriation or other authority (Categories B and D): For 2023/24, the Government’s financial statements reported eight instances of expenditure that were without authority when it was incurred – that is, without parliamentary appropriation or without Cabinet’s prior approval to use imprest supply.

- In excess of appropriation or other authority (Categories C and E): For 2023/24, the Government’s financial statements reported 11 instances of expenditure that was above the maximum allowable amount when it was incurred.

2.14

When it is anticipated that expenditure will be incurred above the appropriation limits, departments should seek prior Cabinet approval to use imprest supply. However, imprest supply is only an interim authority, so all expenditure using this authority must also be appropriated through an Act of Parliament by 30 June (see Appendix 2 for how appropriations work).

2.15

Sometimes Cabinet’s approval to use imprest supply is obtained, but the extra authority is not included in an Appropriation Act before the end of the financial year. In these instances, the expenditure remains unappropriated.

2.16

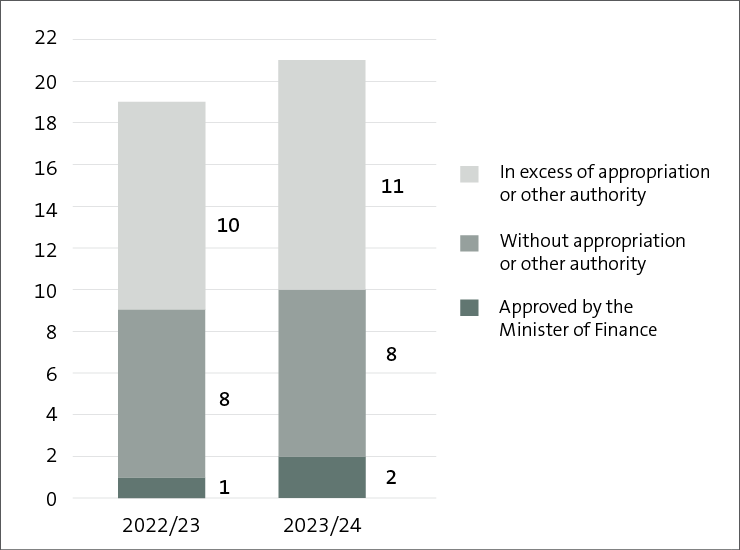

Figure 3 shows a slight increase in the incidence of unappropriated expenditure in 2023/24, with two more instances than for 2022/23. (Figure 6 sets out the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure from 2018/19 to 2023/24.)

Figure 3

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2024

Note: The reported 2022/23 amount has been revised to reflect confirmed instances identified in the current year that relate to the previous year.

2.17

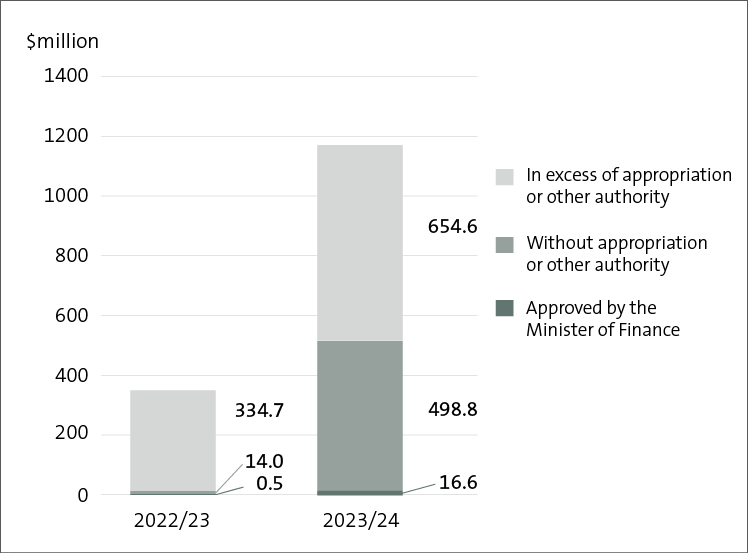

Figure 4 compares the dollar amounts of unappropriated expenditure for 2022/23 and 2023/24. The amount of unappropriated expenditure in 2023/24 ($1,170.1 million) was more than triple that for 2022/23 ($349.251 million).24 It has also trebled as a percentage of the Government’s budget. The $1,170.1 million for 2023/24 was 0.62% of the Government’s final budgeted amount for that year, compared with 0.2% for 2022/23.

Figure 4

Amount of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2024

Note: Figure 5 explains why the amount has increased.

2.18

The increase in the dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure is primarily attributable to two instances in Vote Revenue and Vote Finance.

2.19

For Vote Revenue, the expense associated with writing down the value of debtors25 (that is, the debt impairment and debt write-off expense) because of a reclassification of debt exceeded the amount appropriated for this purpose by $513 million (see paragraphs 2.53-2.54).

2.20

Vote Finance included an appropriation in 2022/23 to incur expenditure relating to the provision for contributions to councils affected by the severe weather events in the North Island. However, it was determined that the provision and expense should be recognised in 2023/24, when no appropriation or other authority was in place, resulting in unappropriated expenditure of $494.5 million (see paragraphs 2.67-2.69).

2.21

These two instances constitute 86.1% of the $1,170.1 million of unappropriated expenditure for 2023/24. Without these Vote Revenue and Finance items, the value of unappropriated expenditure would have been $162.59 million – 0.09% of the Government’s budget.

Why was the expenditure unappropriated?

2.22

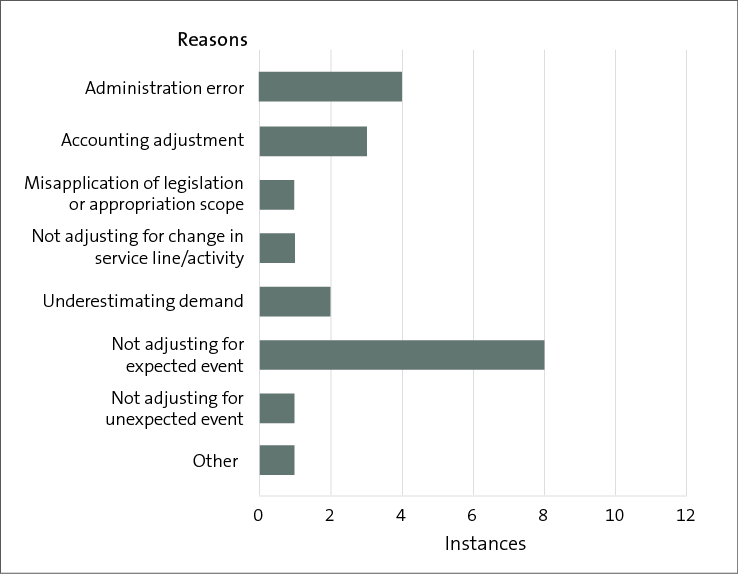

Figure 5 shows the reasons why unappropriated expenditure occurred and lists the number of instances against each of the eight reasons. The classification of reasons is based only on the root cause of the unappropriated expenditure. Once again, administrative errors continue to feature.

2.23

Four of the 21 instances resulted from administrative oversights, but they account for less than 2% of the value of unappropriated expenditure. Such errors should be avoidable. Not adjusting an appropriation for an expected event gave rise to eight instances, amounting to 45.2% of the value of unappropriated expenditure.

Figure 5

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure in 2023/24, by number of instances

Administration error

2.24

Four instances of unappropriated expenditure resulted from administrative oversights. These were in Vote Ombudsmen, Vote Health, and Vote Business, Science and Innovation.

2.25

Two of the instances were because capital injections were incorrectly requested and transferred from the Crown to the Office of the Ombudsman and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE).

2.26

Under section 12A of the Public Finance Act 1989, the Crown must not make a capital injection to a department (other than an intelligence and security department) or an Office of Parliament unless an Appropriation Act authorises the capital injection.

2.27

The Crown made a capital injection with no authority to the Office of the Ombudsman. The Office of the Ombudsman incorrectly interpreted an adjustment to its capital expenditure appropriation as authority for a capital injection. It requested and received an unauthorised cash injection of $2.58 million, which it returned when the error was identified.

2.28

The Crown also made a capital injection to MBIE with no authority. Vote Business, Science and Innovation included capital injection authority to cover $13.1 million in assets transferred to MBIE. However, MBIE requested and received $13.1 million in cash, despite already having received $13.1 million in assets (which constituted a capital injection). The cash received exceeded the capital injection authority.

2.29

Administrative errors at MBIE meant that two contracts related to the Innovation Partnerships Programme were tracked as departmental expenditure rather than as non-departmental expenditure. Because the expenditure was not managed as part of the non-departmental appropriation, it exceeded appropriation by $390,000.

2.30

When departments need an increase in expenditure authority, they must seek it in a timely manner and ensure that it has been appropriately approved before they incur the expenditure.

2.31

The Ministry of Health sought an increase in authority to its Legal Expenses appropriation for increased costs associated with new proceedings, historical abuse claims, and Covid-19 litigation. Although the Ministry sought the authority in March, it was not approved until April. This resulted in expenditure under Vote Health being unappropriated.

Accounting adjustments

2.32

During 2023/24, the Ministry of Transport identified that historical accounting for expenditure under the Bad Debt Provisions appropriation in Vote Transport was incorrect. Once revised, an increase in the provision caused expenditure to exceed the amount authorised.

2.33

Similarly, after an extensive review, the Ministry of Education adjusted its cost allocation model to more accurately align the allocation of costs to where funding is provided. The Ministry’s improvements increased the amount allocated to Vote Education’s Primary and Secondary Education multi-category appropriation, causing expenditure to exceed the appropriation limit by $16.1 million.

2.34

In 2021/22, MBIE carried out a review of the Cloud venue on Auckland’s Queens Wharf. As a result of the review, the expected useful life for this asset was revised downward. When the estimate of an asset’s life is reduced, its book value needs to be depreciated over a shorter period of time (that is, over its revised remaining life). This means that the annual depreciation expense will be higher than it was before.

2.35

However, MBIE did not incorporate the reduction in useful life of the Cloud into its depreciation calculation until 2023/24. After updating the calculation, the depreciation expense exceeded the appropriation Economic Development: Depreciation on Auckland’s Queen’s Wharf for the last three years (2021/22 to 2023/24). Unappropriated expenditure under Vote Business, Science and Innovation for this item was $811,000 in 2023/24 and a total of $661,000 for the previous two years.

Misapplication of legislation or appropriation scope

2.36

The Ministry of Social Development supports families with children who are living in emergency housing accommodation and who are eligible for the Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants. This assistance must meet the criteria set out in the Social Security Act 2018. One criterion requires dependent children to be under 18 years old.

2.37

The Ministry made payments for special assistance under the Flexible Funding Welfare Programme that did not meet the “under 18 years old” criterion. Consequently, expenditure under Vote Social Development’s Emergency Housing Support Package appropriation exceeded authority by less than $1,000.

Change in activity

2.38

One instance of unappropriated expenditure in 2023/24 resulted from a government department funding a new class of service providers without checking that it had parliamentary authority for the related expenditure.

2.39

The Ministry of Justice provides support to community-based justice services. This expenditure is authorised by the multi-category appropriation, Community Justice Support and Assistance.

2.40

The appropriation authorises payments for community-based legal advice, assistance, and representation services. However, the Ministry made payments to providers that represent and support agencies that provide community-based legal advice, as well as providers who directly deliver community legal services. Expenditure incurred on the former ($527,000) was outside the scope of the appropriation.

Underestimating demand

2.41

It is often difficult for government departments to accurately forecast the demand for some activities. During 2023/24, two instances of unappropriated expenditure resulted from the Ministry of Education and Te Arawhiti (a departmental agency within the Ministry of Justice) underestimating demand and associated costs in Vote Education and Vote Te Arawhiti.

2.42

The Ministry of Education forecasts the expected amount of subsidy that licensed and certificated services need to deliver early learning services to children under six years of age. However, demand for early learning services for 2023/24 was higher than the Ministry expected. The Ministry’s under-forecasting led to subsidy payments exceeding the Early Learning appropriation limit by $100.7 million.

2.43

Costs associated with continuing litigation and court proceedings are often unclear until they have been completed. Depending on the outcome, costs can be higher or lower than anticipated.

2.44

The Ministry of Justice, under Vote Te Arawhiti, incurred expenditure under the appropriation Crown Response to Wakatū Litigation and Related Proceedings. The costs associated with significant senior-level legal input and a range of expert witnesses called by the Crown exceeded Te Arawhiti and the Ministry’s forecast. This resulted in $921,000 of unappropriated expenditure.

Not adjusting for expected event

2.45

After the Budget has been passed, departments should regularly monitor their activities and events, and update their forecasts accordingly. If needed, they should seek additional spending authority if they forecast that expenditure will be higher than the existing appropriation authority or if an upcoming event is outside the scope of an appropriation.

2.46

During 2023/24, eight of the 21 instances of unappropriated expenditure were because of departments not adjusting their forecasts or not seeking additional spending authority for expected events. Good budget management would avoid such unappropriated expenditure.

2.47

Most appropriations are limited to a single financial year.26 If expenditure could occur beyond that financial year, government departments must gain authority for the following year, regardless of whether expenditure in the earlier year was below the maximum amount authorised for that year.

2.48

Of the eight instances of departments not adjusting for expected events, three were caused by departments incurring expenditure in the year after the year that they had an appropriation for.

2.49

Inland Revenue processed additional valid claims for Covid-19 support and Covid-19 resurgence support after 30 June 2022. However, it only had expenditure authority until 30 June 2022. It approved and made payments for these claims during the next two years without appropriation in Vote Revenue. This unappropriated expenditure was $1.1 million in 2022/23 and $2,400 in 2023/24.

2.50

Similarly, the Ministry of Transport had an appropriation in 2022/23, Supporting a Chatham Islands Replacement Ship, under Vote Transport. This authorised payments for short-term maintenance of the existing vessel. There was no appropriation in Budget 2023 for 2023/24.

2.51

Although the maintenance work was expected to be completed by 30 June 2023, work continued and expenditure was incurred in 2023/24. The Crown was obliged to reimburse expenditure for this work. The Ministry incurred unappropriated expenditure of $529,000 in 2023/24 before receiving additional authority under imprest supply.

2.52

Five instances of departments not adjusting, or not adjusting adequately, for expected events resulted in them incurring expenditure that exceeded appropriation.

2.53

For the second year in a row, Inland Revenue’s expenses under Impairment of Debt and Debt Write-Offs exceeded the appropriation limit. It identified adjustments in the classification of debt that was overdue but that had previously been classified as not yet due.

2.54

The reclassified debt was consequently impaired at the overdue debt rates. This, along with revisions to previous years’ interest and penalties remitted as part of the Covid-19 response, increased the impairment expense. Inland Revenue had anticipated the increase in impairment expense and obtained a significant increase in authority to cover it. However, the increase was not enough, resulting in $513 million of unappropriated expenditure under Vote Revenue.

2.55

The Ministry of Education exceeded the expenditure limits in Vote Education for both the Outcome for Target Student Groups and the Oversight of the Education System multi-category appropriations.

2.56

After therapist pay equity claims were settled, the Ministry made a correction to pay rates and parental payments for those who return to work from parental leave. It also adjusted the level of reimbursements to therapists who are required to pay for annual practising certificates or membership fees for a professional body.

2.57

The corrections resulted in expenditure exceeding the Outcome for Target Student Groups appropriation by $531,000.

2.58

Expenditure exceeded the Oversight of the Education System appropriation limit by $5.3 million because of increased redundancy costs associated with the Budget 2024 savings programme.

2.59

Vote Transport includes a multi-category appropriation, Mode-Shift – Planning, Infrastructure, Services, and Activities. This appropriation funds expenditure by third parties for services and activities that reduce the public’s reliance on cars and support them to take up active and shared travel modes, such as walking, cycling, and public transport.

2.60

Under the Transport Choices programme, the Ministry of Transport, through the New Zealand Transport Agency, funds local councils to deliver agreed projects in line with the programme and the scope of the appropriation. The programme was due to expire on 30 June 2024. However, it was extended to 30 June 2025, and a significant amount of funding was transferred from 2023/24 to 2024/25.

2.61

In the Supplementary Estimates, the appropriation authority was reduced from $303.5 million to $100 million for 2023/24, and $54.8 million was provided for 2024/25. Most of this was against the Third-party Projects and Activities category.

2.62

However, many councils still met the 30 June 2024 timeline, and their unanticipated claims resulted in expenditure exceeding the reduced maximum authority ($100 million) by $9.2 million.

2.63

The Ministry for Culture and Heritage needed to increase its provision for settling legal obligations associated with the creation of the Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. This resulted in a $698,000 expense in 2023/24.

2.64

The Ministry determined that neither its appropriation for the Maintenance of War Graves, Historic Graves and Memorials nor any other appropriation in Vote Arts, Culture and Heritage covered this sort of expense. Therefore, it incurred the expenditure without appropriation.

Unexpected events

2.65

The New Zealand Customs Service collects revenue from the import and export of goods on behalf of the Crown. In March 2024, Customs issued an assessment of the duty and compensatory interest that an importer owed for importing six tonnes of illicit tobacco. Even though the tobacco was imported illegally, duty must still be charged on it because tobacco is a legal product.

2.66

In June, Customs deemed that it was unlikely to recover the amount of duty and interest owed because of the importer’s imprisonment and lack of assets. The write-off of the duty and compensatory interest resulted in expenses exceeding the Change in Doubtful Debt Provision appropriation by $9.9 million.

Other

2.67

In early 2023, New Zealand was hit by two separate extreme weather events. The Auckland Anniversary Weekend floods and Cyclone Gabrielle caused widespread catastrophic flooding throughout large parts of the North Island.

2.68

The Government had anticipated that expenditure relating to provisions for contributions to affected councils would be incurred during 2022/23, and Vote Finance included an appropriation to cover the expense.

2.69

However, after 2022/23, it was determined that the Crown’s obligation arose in 2023/24. The provision and associated expense were therefore recognised in 2023/24, with no appropriation in place. As a result of the timing for recognising the obligation, expenditure of $495 million was incurred without appropriation. The unappropriated expenditure was reported under Vote Finance.

How does 2023/24 compare with previous years?

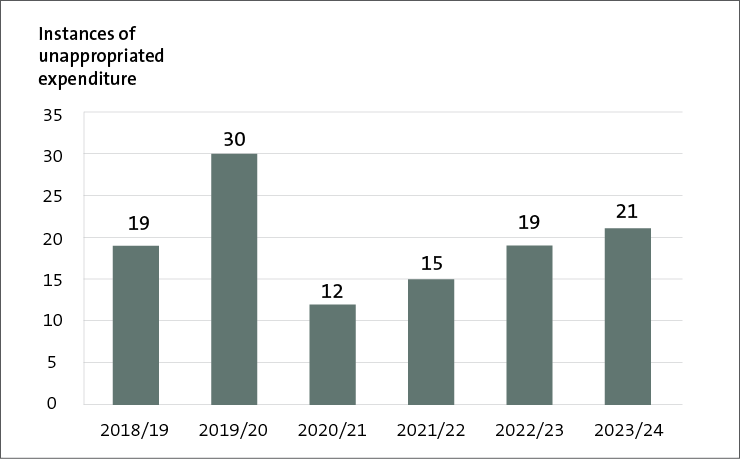

2.70

There has been a steady increase in the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure since the historical low of 12 instances in 2020/21. As Figure 6 shows, the number has risen to 21 in 2023/24.

Figure 6

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure, from 2018/19 to 2023/24

2.71

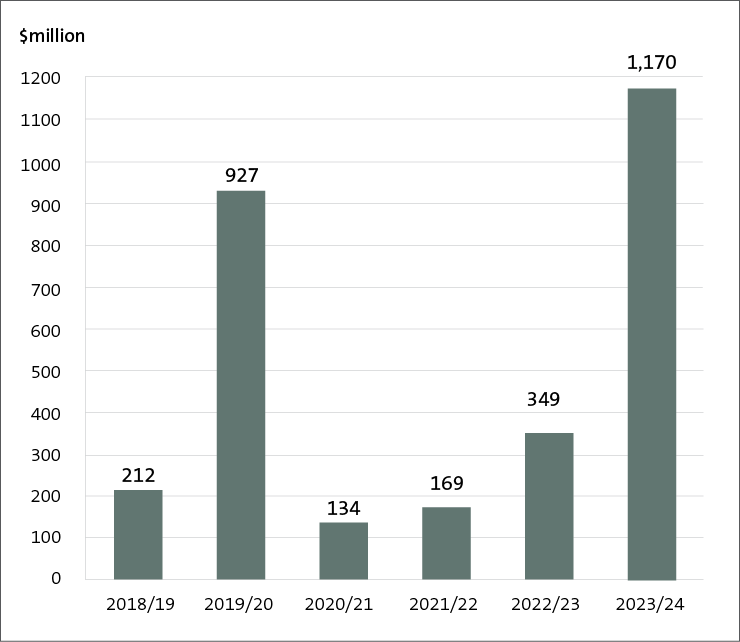

Figure 7 shows the dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred during the last six years. The value of unappropriated expenditure follows the usual fluctuations over time, with the values for the two outlier years resulting from one large instance (2019/20) and two large instances (2023/24).

2.72

As we explained in paragraph 2.21, 86.1% of unappropriated expenditure for 2023/24 is attributable to two instances – debt write-offs and write-downs under Vote Revenue and the North Island severe weather events under Vote Finance.

Figure 7

Amount of unappropriated expenditure, from 2018/19 to 2023/24

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure over time

2.73

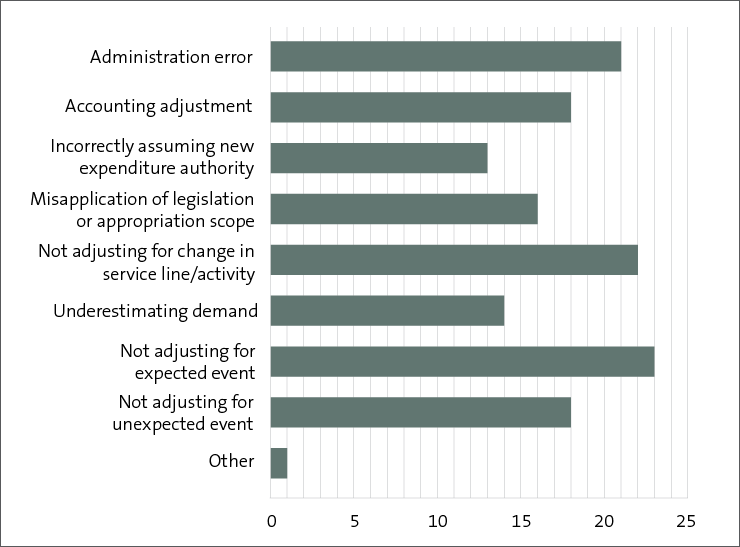

Figure 8 shows the reasons why unappropriated expenditure occurred over nine years and how frequently it occurred for each reason.27

Figure 8

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2023/24, by number of instances

2.74

In recent years, the most common reason for unappropriated expenditure was departments not adjusting for expected events (23 instances, which is 15.8% of all instances). Eight of these instances occurred in 2023/24.

2.75

If existing appropriations do not cover the expenditure from the expected event, departments need to seek authority under imprest supply before incurring the expenditure.

2.76

The second most common reason is the failure to secure spending authority to cover changes in departmental functions, services lines, or activities.

2.77

Thirty-six percent of instances resulted from administration (21) or accounting (18) adjustments or other failures in appropriation management (13). These should be avoidable.

2.78

Administration errors include mistakes that departments make when they seek additional authority for spending between Budgets.28 Departments also make errors when they transfer funding from one appropriation to another, reducing the spending limit of the original appropriation.

2.79

In some instances, the department calculated the transferred amount incorrectly. In others, it appears that the department made the transfer without enough awareness of the likely future expenditure. Government departments need to diligently manage and monitor the way that they move funding and change spending authorities during the financial year (that is, between Budgets).

2.80

Accounting adjustments relate mainly to the misapplication of accounting rules, commonly referred to as “generally accepted accounting practice” (GAAP). For the most part, GAAP is specified in financial reporting standards, which determine how government departments’ financial statements recognise, classify, measure, and report expenditure.

2.81

The accounting treatment of an item has implications for the type of expenditure authority needed. The most common problem involves determining whether expenditure is capital or operating. Operating expenditure needs an operating expense appropriation, and capital expenditure needs a capital expenditure appropriation.

2.82

If departments account for expenditure incorrectly, the subsequent correction of the error might result in expenditure not being covered by the correct appropriation type. Government departments must ensure that they properly think through the GAAP accounting implications for all their expenditure. In turn, they must identify and properly manage the implications for appropriations from the accounting treatment.

2.83

During the last nine years, 13 instances of unappropriated expenditure occurred because departments failed to manage the timing of and needed authority for expenditure. The most common reason why these instances occurred involved departments receiving Cabinet’s “in principle” agreement to have funding and spending authority transferred from one financial year to the next (in-principle expense transfers, or “IPETs”).

2.84

IPETS are not included in the annual Budget and do not authorise expenditure. All IPETs need to be formally confirmed or otherwise in the new financial year (usually in October). If confirmed, then the department must receive explicit approval to use imprest supply to cover that expenditure. It is positive to see that there have been no errors of this nature in the last several years.

2.85

Another common reason is when government departments fail to keep spending within the scope of what the law allows (16 instances).

2.86

Departments need to understand what their appropriations may and may not cover and regularly review their practices to ensure that they align with the relevant authorities. The appropriation scope limits what departments may spend public money on - they cannot spend money on activities that are outside the scope of their appropriations. When the scope of the appropriation is tied to legislation or regulation, and the legislation or regulation has changed, departments must ensure that their practices remain aligned to the revised authority.

2.87

There have been 14 instances of unappropriated expenditure in the last nine years because demand-driven expenditure exceeded the forecast spending. Unexpected demand can arise from situations that could not reasonably have been foreseen. However, it can also arise from situations that departments should have anticipated and provided for.

2.88

In Figure 8, the reason “Not adjusting for expected event” (23 instances) refers to unappropriated expenditure that occurred because of specific events that the department should have anticipated.

2.89

However, unappropriated expenditure can also arise as a direct result of “unexpected events” – that is, where we would not expect departments to know that they would need additional authority before the event happens. Such events resulted in 18 instances of unappropriated expenditure during the last nine years. They can include expenses relating to sudden asset impairments, and obligations placed on the Crown at short notice.

2.90

In the last several years, we have seen costs associated with unexpected severe weather events and the Covid-19 pandemic result in unappropriated expenditure.

Work carried out to discharge the Controller function

Monitoring public expenditure

2.91

During 2023/24, we monitored public expenditure to determine whether it was in line with the authority that Parliament provided.29

2.92

We checked that the amount of new “between-Budget” expenditure agreed by Cabinet (that is, the use of imprest supply) remained within the $28.5 billion authorised through the second annual Imprest Supply Act.30 We also checked a sample of changes made to individual appropriations during the year to ensure that they had been properly authorised.

Audits of government departments

2.93

We carry out the core of the Controller work through annual audits of government departments and associated interactions with those departments.31 As part of our audits, we examined the financial systems and financial records of government departments to determine whether public expenditure has been properly authorised and accounted for.

2.94

If the Government incurred expenditure above or beyond what Parliament had authorised, we checked that the nature and amount of unappropriated expenditure was accurately reported to Parliament and the public.32

Multi-year appropriations

2.95

As an Office of Parliament, we are interested in ensuring that the system and arrangements for Parliament to authorise government expenditure continues to operate as intended. We recently, we examined the use of multi-year appropriations (MYAs) for authorising public expenditure.

2.96

MYAs provide more flexibility for government spending. They are an exception to the usual way of authorising expenditure through annual appropriations. MYAs should be used sparingly and not when an annual appropriation should be used.

2.97

We found that there has been a marked increase in the use of MYAs, from 20 in 2008 to 59 in 2016 to 167 in 2023. We also found some examples of expenditure under MYAs that we consider should have been authorised under annual appropriations. We reported our findings on our website in May 2024.33 We called for the Government to review the use of MYAs to ensure that they are being used appropriately, in line with the Treasury’s guidelines. We will continue to monitor this area.

Resolving issues and providing advice

2.98

Much of the Controller responsibilities include considering matters where the question of whether public expenditure is unauthorised is not straightforward or, at least, needs some consideration before a conclusion is drawn.

2.99

From time to time, government departments seek the Controller’s view on a matter to gain assurance about the lawfulness of spending or to help alert them to the need to seek additional spending authority. At other times, our appointed auditors, the Treasury, members of Parliament, or the news media will draw our attention to matters that need deeper scrutiny and consideration.

Helping to improve capability and promote good appropriation management

2.100

We continued to support the Treasury’s Finance Development Programme by delivering seminars to government department finance professionals. In those seminars, we highlighted the importance of parliamentary control of Crown spending, how the Controller function supports New Zealand’s constitutional arrangements, the importance of obtaining proper authority for government expenditure, and some of the common problems that can lead to unappropriated expenditure.

18: Section 22 of the Constitution Act 1986.

19: Appropriations are authorities from Parliament that specify what the Crown may incur expenditure on (specific areas of expenditure). Most appropriations specify limits in terms of the type of expenditure (the nature of the spending), scope (what the money can be used for), dollar amount (the maximum that can be spent), and period (the time frame that the authority is given for).

20: For ease of discussion, we include the unauthorised capital injection numbers within the unappropriated expenditure totals.

21: The Controller is concerned with Government “expenditure”. We sometimes use the terms “spend” or “spending” for readability.

22: That is, it is within the type, scope, dollar amount, and period limits that Parliament authorised.

23: New Zealand Government (2024), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2024, Wellington, pages 154-163.

24: New Zealand Government (2024), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2024, Wellington, page 155.

25: Also known as “receivables”.

26: Multi-year appropriations cover several years, and permanent legislative authorities are not time bound.

27: This is the period that we have collected data for.

28: In other words, departments make these mistakes when they seek Cabinet authority to use imprest supply or additional appropriation through the annual Supplementary Estimates Bill.

29: We do this work under section 65Y of the Public Finance Act 1989.

30: Joint Ministers may also approve between-Budget spending under delegation from Cabinet.

31: We do this work under section 15 of the Public Audit Act 2001.

32: We carried out these checks during our audits of the Government’s financial statements and of the financial statements of all government departments, for the year ending 30 June 2024.

33: See “The increasing use of multi-year appropriations” at oag.parliament.nz.