Part 2: The Electoral Commission and the 2023 General Election

The Electoral Commission's role and functions

2.1

The Electoral Commission is an independent Crown entity established under section 4B of the Electoral Act 1993. The Electoral Commission operates independently in running elections but is accountable to the Minister of Justice for its performance. It is monitored by the Ministry of Justice.

2.2

The Electoral Commission was formed by merging the former Electoral Commission and Chief Electoral Office into a single Electoral Commission in 2010. Enrolment functions that were previously administered by the Electoral Enrolment Centre at NZ Post were transferred formally to the Electoral Commission in 2012, although NZ Post continued to process enrolments under a delegation from the Electoral Commission. This function was brought entirely in-house in 2016.

2.3

The Electoral Commission is governed by a board of three – the Chief Electoral Officer (who is also the Chief Executive of the Electoral Commission), an appointed Chairperson, and a Deputy Chairperson. Two Electoral Commission Board members were appointed in August 2019 and the current Chief Electoral Officer was appointed in 2022.

2.4

We note that the governance structure is small given the critically important role of the Electoral Commission. Because the Chief Electoral Officer is on the Board, there may be an unclear separation between governance and management. Although the recent Independent Electoral Review did not recommend changes to the structure of the Board, it suggested that the board size be increased from three to five.5 This would require a change in legislation because membership of the board is set out in the Electoral Act 1993 (section 4D(1)).

2.5

In 2022, a structural change occurred and the present executive leadership team of seven was created, reporting directly to the Chief Executive. Five of the seven executive leadership team were relatively new and the 2023 General Election was the first election they had managed.

2.6

The Electoral Commission is responsible for running general elections, by-elections, and referenda, as well as encouraging participation and confidence in the electoral process, promoting understanding about the electoral system, and providing policy advice on electoral matters.6 The Electoral Commission also supports the work of the Representation Commission, which carries out the regular electorate boundary reviews that occur after each census.7

2.7

The Electoral Act contains detailed provisions about how the election should be run, including voting processes, checking the validity of votes, and declaring the official result.8 Many of the processes are manual.

2.8

The Electoral Commission operates and plans within a three-year election cycle. The first year after a general election provides an opportunity for the Electoral Commission to review the past election and propose, define, and design operational changes for the next election. The second year involves preparing for the election, and the election takes place in the third year.

2.9

Running a successful general election is core to the Electoral Commission's role and is a significant and complex undertaking. The election is challenging to manage – it is a large event, dispersed across New Zealand, and held over a period prescribed by legislation. It includes maintaining the Māori and General electoral rolls (so that those who are able to vote can do so), running enrolment campaigns, and enabling voting through a range of methods, both across New Zealand and overseas. The core staff of about 170 (full-time equivalent) increases to about 22,000 during the election period. The Electoral Commission needs to procure a large volume of supplies and find voting places and electorate headquarters to accommodate electorate activities throughout the country, as well as setting up storage, security, and logistics arrangements.

2.10

Regional managers start work about 18 months before the estimated election date to prepare regional plans, establish electorate headquarters, and recruit and train election workers. Election workers are employed on a temporary basis during the election period. In 2023, the electorate managers and regional managers remained employed until early December, two months after the election.

2.11

The Electoral Commission's planning for the 2023 General Election was informed by its review of the 2020 General Election and previous elections.

2.12

The Electoral Commission's personnel and budget changes over the three-year election cycle. The Commission's functions and delivery models can also change when legislation is amended, such as changes made to enable election day enrolling and voting. There was also a legislative amendment made in 2022 to enable Māori electors to change which electoral roll they are on up until three months before the election.

Funding to prepare for, and run, an election

2.13

Running an election involves recruiting and training large numbers of personnel in a short period, leasing premises for voting places and electorate headquarters, and securing storage facilities. It also requires bespoke information technology infrastructure, security, supplies, logistics, and communications resources.

2.14

The Electoral Commission told us that it did not know how much funding it would have to administer the 2023 General Election until May 2022.

2.15

In the two years before the election, the Electoral Commission had a financial deficit and used reserves to fund operational activities. The Electoral Commission has said it does not have reserves left to do this now.

2.16

In Budget 2022, the Electoral Commission received $229 million in funding for the three-year election cycle for the 2023 General Election, to provide electoral services, to enable enrolment and voting on election day, and to increase capability. This multi-year appropriation gave some flexibility to the Commission to draw funds between the years of a single electoral cycle. Additional funding of $4.1 million was provided for the three by-elections that occurred during this cycle: Tauranga, Hamilton West, and Port Waikato.

2.17

The current multi-year appropriation for the Electoral Commission will end in mid-2024, and the funding available to run the next general election will be known after the May 2024 Budget. The Electoral Commission said in its Briefing to the Incoming Minister in 2023 that it will be providing further advice on the implications of cost pressures on its ability to run and maintain the integrity of elections.

2.18

The Government sets the funding available to the Electoral Commission to run elections. It is not for us to form a view on whether the Electoral Commission's funding is adequate. The Electoral Commission described to us the challenges it faced managing the election cycle within the available funding and funding structures. The Electoral Commission told us that in 2023 it faced budgetary pressure because of increased costs for personnel and property leasing (for both electorate headquarters and voting places), as well as increased paper, printing, and postage costs.

2.19

In non-election years, the Electoral Commission plans and implements improvements to systems and processes for future elections. The Electoral Commission told us that in 2023 it did not have enough funding to retain regional and electorate managers to review the previous election and inform future practices beyond early December.

2.20

We note that internationally there has been a trend towards establishing independent organisations to manage election processes. Typically, these organisations are not accountable to a government ministry or department and have budgetary independence.9 For example, the New South Wales Electoral Commission is not subject to the Department of Premier and Cabinet Office financial management processes. Instead, a specialist integrity unit in the Treasury manages funding requests.10 In British Columbia, a Legislative Assembly Committee recommends funding for the Chief Electoral Officer and other integrity agencies.11

2.21

We understand that Cabinet asked officials to provide further advice on sustainable funding models for the Electoral Commission in 2019, but the Electoral Commission told us that this did not occur due to the Covid-19 pandemic. A multi-year appropriation was put in place to help address funding timing challenges. The Electoral Commission has previously proposed a permanent legislative authority to provide funding independence and guard against a perception risk that funding levers could be used to compromise election stability by reducing funding.

The 2023 General Election

2.22

To be eligible to vote, a person needs to be 18 years of age or older, a New Zealand citizen or permanent resident, and have lived in New Zealand continuously for 12 months or more at some time in their life.12

2.23

The Electoral Act 1993 requires the Electoral Commission to carry out what is known as an "elector inquiry" to update the electoral rolls before the General Election.13 The Electoral Commission mails out an enrolment update pack to all registered voters and carries out public awareness and community engagement campaigns encouraging people to register or to update their registration details. For the 2023 General Election, this happened between 31 July and 9 September 2023.

2.24

In November 2022, a law change enabled voters of Māori descent to change which electoral roll they were on (Māori or General) up until three months before the general election. This meant that the Electoral Commission had to change the enrolment system and carry out community engagement and a public information campaign on the law change. Previously, Māori electors could change which roll they were on only once every five or six years.

2.25

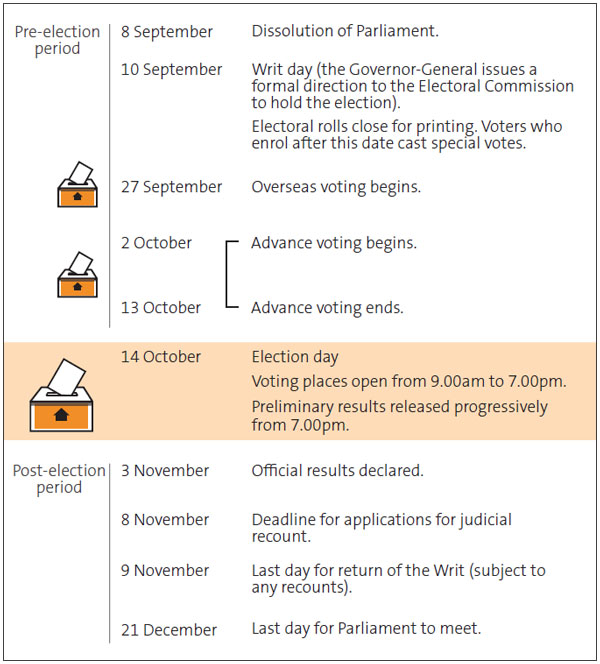

On 10 September 2023, the Governor-General formally announced the election date and the last day for nominations of candidates, known as "Writ Day". The electoral rolls as at Writ Day are printed and distributed to each electorate to be used during the voting period. Writ Day is the formal start of the 60-day election period. The end of the election period is known as "the return of the Writ", which happens after the elections results are announced. See Figure 1 for a simplified timeline of the 2023 General Election.

Figure 1

Timeline of the 2023 General Election

2.26

A general election has three phases – a pre-election period (when advance voting takes place), election day (the final day of voting, when the preliminary count of most ordinary votes takes place), and a post-election period (when the official count takes place).

2.27

The 2023 General Election was held on 14 October. The Electoral Commission set up 829 advance voting places, and 2334 voting places for election day. This was fewer voting places than in the 2020 General Election, but there had been a significant increase in voting places in 2020 to reduce the spread of Covid-19.

How the 2023 General Election differed from previous elections

2.28

Voter turnout in 2023 was slightly lower than in 2020 (2,858,869 - 78% of eligible voters, compared with 2,894,486 - 82% in 2020). There were 463,276 fewer advance ordinary votes and 17,346 fewer advance special votes cast than estimated.

2.29

Ordinary votes are votes cast by enrolled voters at a voting place in the electorate in which they live. Special votes are votes cast by voters who enrol after Writ Day, need to update their enrolment details, are on the unpublished roll, or are outside of their electorate (including people voting from overseas). Special votes must, by law, be transported back to the electorate they belong to and be validated before they can be counted. An exception is made for overseas and dictation votes, which are compiled at a centralised processing centre.

More people enrolled after Writ Day and voted later than they did in 2020

2.30

To increase voter participation and to reduce the number of disallowed votes, in 2019 the Electoral Act 1993 was amended to allow election-day enrolling and voting.14 The 2023 General Election was only the second general election where people had been able to enrol and vote on election day.

2.31

When the change was proposed, the Ministry of Justice15 told Cabinet that the change could increase operational pressures in the election period, increase the number of enrolments needing to be processed before rolls were closed for the official count, and reduce the time for processing enrolments before the official count – potentially delaying the official result.16 The Ministry of Justice proposed:

- extending the period for the return of the Writ from 50 to 60 days;

- increasing election day resourcing by 2800 full-time equivalent staff, at a cost of an extra $13.4 million; and

- introducing an electronic roll that could be used to mark off electors when people presented to vote (offering efficiencies later in the vote counting process).

2.32

The change was implemented and the period for returning the writ was extended to 60 days. The Electoral Commission told us it had sought $158.6 million of funding over four years, including $13.422 million to support enrolment on the day, but received $75.6 million of funding over four years for operating costs, including supporting enrolment and voting on election day. Capital funding was not allocated to develop the functionality to mark electors off on an electronic roll.

2.33

The Electoral Commission told us that the significant change in voter behaviour was unexpected, with more people than estimated enrolling in the last two weeks leading up to election day and on election day. Even before the legislative change, there had been a trend since 2011 of people increasingly enrolling after Writ Day, but the 2023 numbers represented a 125% increase on the 2017 numbers for the same period.17 Although people can continue to enrol up to and including on election day, they need to cast a special vote because their details were not on the electoral rolls by Writ Day. The extent of the change in voter behaviour was unanticipated and put pressure on people and systems because the demand had increased beyond initial projections.

2.34

In 2020, 310,471 people enrolled in the voting period, including about 80,000 on election day. In 2023, 453,940 people enrolled during the voting period, including about 110,000 on election day. This was a 46% increase on 2020 numbers of people enrolling in the voting period. The number was considerably higher than the Electoral Commission's projections (that 319,000 people would enrol in the election period), which the Commission had used to estimate the number of staff needed to process enrolments and count votes.

There were more special votes than expected

2.35

The number of special votes increased significantly compared with the 2020 General Election. There were 602,000 special votes cast in the 2023 General Election, 100,000 more than in 2020. Special votes require more intensive checks to ensure that voters are enrolled and eligible to vote in the electorate that they are casting a vote for. This increases the amount of time needed to process the vote through the count process. Special votes take about 10 times longer to issue and process than ordinary votes.

2.36

The Electoral Commission has a computer application that allows election workers to look up voters on an electronic version of the electoral rolls and make address changes within the same electorate. On election day, the application experienced two outages, meaning election workers could not look up voters or update voter address details on the electronic roll.18 Staff at voting places were advised to revert to using their paper-based reference rolls until the application was fixed.

2.37

People we interviewed told us that the outages caused uncertainty at voting places and resulted in a higher-than-expected number of people being directed to cast special votes. This was because voters who otherwise could have updated their address within the same electorate, or voters who could not confirm they were enrolled or that their enrolment details were correct, were directed to complete a special vote. We have not been able to quantify the extent to which the outages contributed to more special votes.

2.38

The significant number of special votes put further pressure on the team responsible for processing enrolments and for checking whether voters were enrolled, eligible to vote, and in which electorate.

2.39

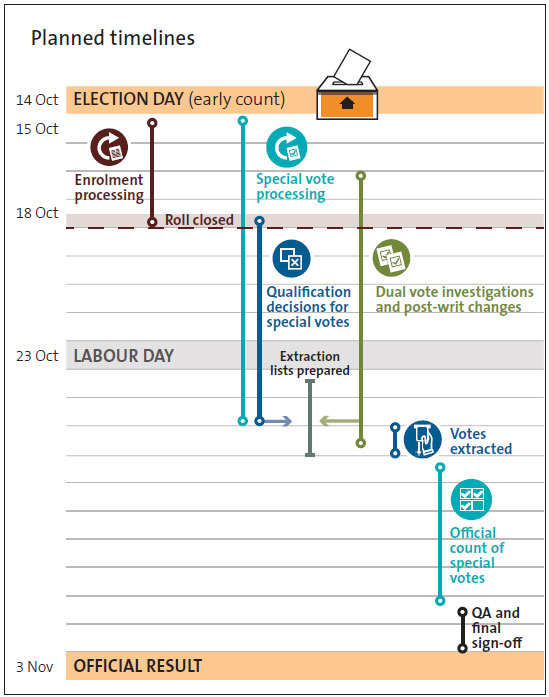

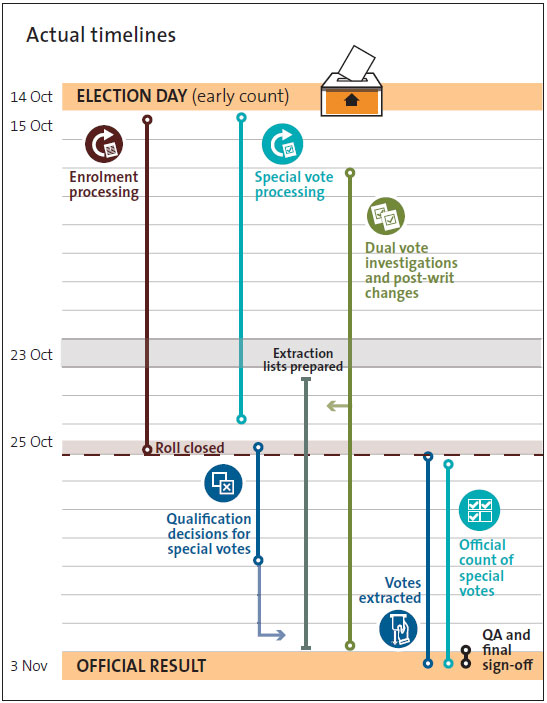

The delay in processing enrolments had a compounding effect on subsequent post-election vote count processes, including qualifying special votes (that is, checking that the special voter's enrolment eligibility meets the criteria to be counted), investigating potential dual votes, extracting votes that were not eligible to be counted, and carrying out quality assurance (QA) checks. We discuss this in more detail in paragraphs 4.50-4.74.

2.40

Figure 2 shows the planned timelines for post-election period activities, compared with the actual timelines.

Figure 2

Planned and actual timelines for the official count for the 2023 General Election

5: Independent Electoral Review (2023),Final Report: Our Recommendations for a Fairer, Clearer, and More Accessible Electoral System, pages 400-401, at justice.govt.nz.

6: The Electoral Commission (2023), "Briefing to the incoming Minister", at elections.nz.

7: The Electoral Commission (2023), "Briefing to the incoming Minister", page 4, at elections.nz.

8: Electoral Act 1993, sections 175-179, at legislation.govt.nz.

9: Norris, P, Frank, RW, and Martinez, C (2014), Advancing Electoral Integrity, page 95.

10: Macdonald, A (2023), "NSW integrity agencies receive $228.6m Budget boost", at themandarin.com.au.

11: New South Wales Public Accountability Committee (2020), Budget process for independent oversight bodies and the Parliament of New South Wales: First report, paragraph 3.84, at parliament.nsw.govt.au.

12: For electoral purposes, a permanent resident is in New Zealand legally and not required to leave within a specific time. There are additional requirements for overseas voters and these requirements were temporarily changed for the 2020 General Election to recognise the impact the Covid-19 pandemic had on international mobility.

13: Electoral Act 1993, section 89D, at legislation.govt.nz.

14: The Treasury (2019), "Regulatory Impact Assessment: Enabling election day enrolment", at treasury.govt.nz.

15: The Ministry of Justice is the monitoring agency for the Electoral Commission and the lead agency for electoral policy issues.

16: The Treasury (2019), "Regulatory Impact Assessment: Enabling election day enrolment", at treasury.govt.nz.

17: The Electoral Commission (2018), "2017 General Election: Electoral Commission report on the 2017 General Election", at elections.nz.

18: The first outage lasted about three hours and the second, after 5pm, lasted half an hour.