Part 5: Informing and involving communities

5.1

A high level of community support, including from iwi, hapū, and Māori, is critical for a council's climate actions to be successful. Community consultation on plans is important, but communities also need to be involved in implementing certain actions.

5.2

Providing timely and meaningful updates to communities on council activities and progress is also an essential part of public accountability.

5.3

We expected to see councils carrying out meaningful engagement and taking consultation feedback seriously – for example, adjusting proposals and plans where feedback indicated changes were needed.

5.4

We also expected public-facing information to enable the public to stay well-informed and engaged in what the councils are doing.

5.5

All four councils have supported their communities to be meaningfully engaged in climate action. Some of the ways that councils have done that vary. Although we saw good examples of progress updates on council websites, we also saw gaps.

5.6

Engaging iwi and hapū about climate-related issues was challenging, to varying degrees, for all four councils.

All four councils have supported meaningful community engagement

5.7

All four councils had taken meaningful steps to inform and involve their communities in climate actions. They provided consultation exercises and surveys for the public to have input in identifying climate responses. They also provided opportunities for community members to be directly involved in planning or implementation through collaboration on specific projects or participation in official advisory bodies.

5.8

We saw all four councils take seriously the value of public consultation about climate change. Between the four councils, consultation has covered:

- identifying climate-related risks to communities;

- the approach the council should take to managing climate-related risks;

- what communities valued and wanted protected from climate-related risks such as coastal inundation; and

- community support for the council proactively addressing climate-related issues.

5.9

We examined how the councils dealt with public feedback to see whether they treated climate-related consultation seriously, and saw that councils consistently gave genuine consideration to public feedback. They frequently modified their approaches or decisions as a result of the feedback they had received (for example, in climate change strategies and LTPs).

5.10

Below we highlight good examples from each council of different approaches to community engagement.

Christchurch City Council's coastal panel

5.11

We noted earlier that Christchurch City Council's CHAP programme involves the use of a coastal panel, a group of community representatives tasked with analysing and identifying preferred adaptation options for their local area. The panel submits those options to the elected members for a decision. Membership of the panel is drawn primarily from the local area that the adaptation planning work is currently focusing on – in this case, Banks Peninsula (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Membership of Christchurch City Council's Coastal Hazard Adaptation Planning Coastal Panel

The coastal panel in the CHAP pilot is drawn from communities around Christchurch:

A Specialist and Technical Advisory Group comprising Christchurch City Council staff, Environment Canterbury staff, and external expertise supports the panel with technical information and advice. |

5.12

Council staff provided the panel with information about coastal hazard risks. Although detailed and technical, members of the panel who we spoke to said the information was understandable and of high quality.

5.13

Council staff also ran local engagement events about the coastal panel's draft adaptation pathways for Lyttelton Harbour and Port Levy. Information provided to the community included coastal flooding scenarios for different levels of sea-level rise.

5.14

We were told that feedback from these engagement events helped the CHAP programme team ensure that it was including the assets most valued by the community alongside the Council's priorities.

5.15

By recording those assets in the Council's online risk mapping tool, we were told that the staff were able to understand the assets' exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts and other hazards. That understanding could then inform conversations with the community about the future of those assets, including possible local adaptation pathways under the Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning process.

5.16

We were told that, although it was not easy, equipping the panel with enough technical knowledge was important to its success. We were told that council staff worked hard early in the process to upskill the panel, provided an effective code of conduct, and made independent specialist and technical advisors available to answer questions.

Christchurch City Council's Major Cycleway Route programme

5.17

Activities that encourage non-car modes of transport, such as the Major Cycleway Routes, are a priority response for Christchurch City Council's climate work. The Major Cycleway Route programme has been under way for more than a decade. In that time, the Council has evolved its approach to seeking public input based on its experience of what has or has not worked well previously. For example, the Council now tailors information packs to specific localities rather than providing extensive detail on an entire proposed route.

5.18

The Council has also found that "pre-engagement" communication with communities is helpful to prepare communities for consultation exercises and to help avoid consultation being misunderstood.

Whanganui District Council's coastal action planning with Ngā Ringaringa Waewae

5.19

Whanganui District Council is trialling an approach of empowering and supporting the community to lead elements of coastal action planning. In 2023, the Council endorsed Ngā Ringaringa Waewae15 to lead community engagement on the rejuvenation of the North Mole area and the Castlecliff portion of the Council's Coastal Action Plan.16

5.20

The community engagement aims to establish a consolidated vision for protecting the Castlecliff area and to inform future actions to build resilience to climate change. Council staff told us that they intend to use what they learn through this process to inform how they can work more closely with the community in other parts of the Council's climate change response. There will be lessons in this for both the Council and the community. Some reflections from Ngā Ringaringa Waewae about the process are set out in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Excerpts from Ngā Ringaringa Waewae's March 2024 report to Whanganui District Council about community engagement

|

Ngā Ringaringa Waewae – kawa-based community collaboration While more time consuming than the more transactional prescriptive engagement of previous phases, invariably what we learnt from these interactions was far richer, nuanced, robust and ultimately helpful. We were able to understand not only the direct aspirations of our community but the fundamental values behind those aspirations, the deep ‘why' that is so easily missed when we only ask for ‘what'. We were able to record the small changes conveyed by community, often overlooked. All of this, documented, will likely prove invaluable for future phases of this emerging process. . . . Importantly our process has encouraged continued community engagement, empowerment, involvement and ownership of rejuvenation outcomes as and when they appear - accepting that when the environment is rehabilitated and empowered, so are the people, and when the people are empowered and engaged so is the environment. Mouri Ora, Mouri Awa, Mouri Tangata. |

Source: Ngā Ringaringa Waewae (2024), Adventures in a Time of Transformation: Delivering Hapū-Led, Community Based Aspirations in Te Kaihau o Kupe | Castlecliff, at ngaringaringawaewae.org.

5.21

Community-led engagement is also one way that councils can seek to provide a climate-related initiative with limited resources. Other councils might be interested in how this could inform their own approaches.

Nelson City Council's Community Carbon Insight Project

5.22

Nelson City Council has actively involved community groups on climate-related issues, including the Nelson Tasman Climate Forum (NTCF).17 As well as providing Nelson City Council with a greater understanding of community views about climate-related impacts and council actions, the NTCF helps the Council to draw on community capacity and expertise in progressing the Council's community-oriented climate-related initiatives.

5.23

One of those initiatives is the Community Carbon Insight Project. Nelson City Council collaborated with several organisations on this initiative, including the NTCF, Tasman District Council, the Nelson Regional Development Agency, an accounting service provider, and an independent sustainability assurance provider.

5.24

We heard that the initiative drew on the strengths and capabilities of the other organisations to measure the carbon footprint of the Nelson-Tasman region at a detailed level. For example, NTCF's research and development group helped identify the methodology, a Tasman District Council officer assisted with data analysis, and others provided free carbon accountancy and assurance services for the project.

Environment Canterbury's rating district liaison committees

5.25

Environment Canterbury uses "rating district liaison committees" to plan and prioritise river management and flood protection initiatives for 58 river and drainage rating districts.18 Large rating districts have dedicated liaison committees. Community representatives are elected to the committees at a public meeting every three years.

5.26

The committees enable community representatives to liaise directly with councillors and council officers on matters relating to setting targeted rates and to help plan and prioritise river control works, flood protection, and flood plain management. They advise and inform Council staff about the state of their district's rivers and the proposed works for the coming year.

5.27

Environment Canterbury's rating district liaison committee meeting notes are publicly available. They indicate a good level of transparency by the Council on work carried out, financial management, and work programme options.

5.28

Rating district liaison committees also make recommendations to the Council on the level of targeted rates (including rate increases) and how those funds should be spent. Although the Council makes the final decisions, we were told that, in relation to one liaison committee, the Council had not rejected a committee recommendation in 30 years.

Some of the councils need to improve how they inform the public about progress

5.29

We saw examples of councils providing engaging and informative public updates on climate-related initiatives. Both Christchurch City Council and Nelson City Council provide useful information on their greenhouse gas emissions initiatives and achievements. Both provide at-a-glance information on their websites, supported by detailed, downloadable analysis and data.

5.30

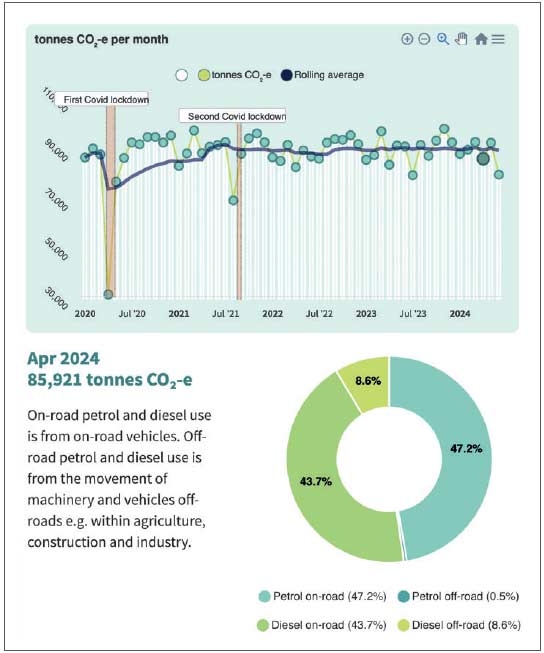

Nelson City Council's graphical information portrays emission reductions since 2017/18. Christchurch City Council's "Smartview" website application provides interactive graphical information on a range of activity counters, such as cycleway usage, to measure the success of its emission-reduction initiatives. Figure 3 shows the Smartview visual for the monthly trend in transport emissions.

Figure 3

Christchurch City Council's Smartview application, showing monthly CO₂ emissions

Source: Adapted from smartview.ccc.govt.nz.

5.31

Christchurch City Council also publishes extensive information about its coastal hazards adaptation planning work. The information includes analysis of what Lyttelton Harbour and Port Levy communities said about what they valued in their coastal environments and what they want the future of their environment to look like.

5.32

Environment Canterbury publishes a range of material about its climate change response. We found the public progress reporting particularly informative in relation to Environment Canterbury's river resilience programme and the rebuilding of flood protection infrastructure after extreme weather events. Flood recovery updates are reported publicly every few months. They are comprehensive and accessible, and cover both physical works as well as financial information. An interactive flood recovery job-map provides high-level status information.

5.33

However, other climate actions that we looked at lacked sufficient public progress reporting. Information was limited, focusing on relatively few initiatives, and was not up to date. Nelson City Council and Whanganui District Council in particular need to consider how – other than emissions reporting – they keep their communities informed of progress with key climate-related initiatives, particularly on climate adaptation planning where communities often have the most interest.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that all councils report publicly on progress with their climate change strategies and work programmes, to support accountability and so communities are well-informed, engaged, and supportive. |

Engaging with iwi and hapū on climate change presents common challenges

5.34

The Local Government Act 2002 requires local authorities to provide opportunities for Māori to contribute to the decision-making processes of the local authority. Iwi, hapū, and Māori can also bring valuable knowledge about local vulnerability to climate-related issues.

5.35

Our recent report on freshwater quality noted the benefits that strong relationships with iwi and hapū can bring to councils' management of natural resources.19 We expected the four councils to have enduring and meaningful relationships with iwi and hapū and to understand their values, interests, and aspirations so that all parties could work towards shared long-term goals for managing the impact of climate change.

5.36

All four councils demonstrated progress and positive outcomes in their engagement with iwi and hapū on climate-related issues. For example:

- we heard strong endorsement from iwi and hapū of Christchurch City Council's efforts on coastal hazards adaptation planning;

- we heard strong endorsement from Ngāti Apa of Nelson City Council's Te Tauihu Capability Initiative, where the Council aims to support Te Tauihu (top of the South Island) iwi groups to measure and understand their operational carbon footprint;

- Whanganui District Council's support of community-led engagement by Ngā Ringaringa Waewae on coastal action planning appears to be serving the Council and its communities well; and

- we saw positive changes in how Environment Canterbury engaged with rūnanga in the second phase of its regional climate change risk assessment, building on experience from the first phase of that work.

5.37

We also identified some common challenges the four councils face when engaging with iwi and hapū on climate-related issues.

Everything is connected

5.38

Councils' general approach to framing climate change, often perceived as being siloed, can be at odds with the fundamentally different relationship with the environment in te ao Māori, where everything is connected.

5.39

We were told that Māori often do not see climate change as the distinct issue that councils tend to present it as. Rather, climate change is part of care and protection of the environment in a more general sense. Iwi and hapū we spoke with would prefer to engage on climate change as part of a wider dialogue about interconnected matters. That approach might not necessarily fit with the way that councils are structurally organised.

5.40

Given this, all councils wanting to engage with iwi, hapū, and Māori on climate-related issues could usefully ask what a workable approach might look like for all parties.

Limited capacity for engagement and competing priorities

5.41

We were told that iwi and hapū have limited capacity to engage with councils on climate change, particularly when they have competing priorities. This issue is well-documented already. It was clearly identified in the Ministry for the Environment's 2019 framework for the national climate change risk assessment.20 Our previous work has also found that frequent requests from the public sector and others for Māori and iwi input and involvement in projects places pressure on their capacity.21 As we have said about public organisations generally, councils need to be mindful that they typically have more capacity than iwi and hapū. This can affect the timeliness, level, and quality of the input that iwi and hapū are able to provide.

5.42

However, we did see examples of councils and iwi and hapū trying to make it work within the resource constraints that each has. In some cases – for example, those noted above – outcomes were positive.

5.43

In others, we heard of dissatisfaction with councils' ability to understand and accommodate the constraints or processes that iwi and hapū often have. These include providing unreasonably short time frames for iwi and hapū representatives to consult with their communities and prepare a considered response.

5.44

We were encouraged by one council's staff awareness of the demands that can be made on some iwi and hapū representatives, recognising that they are "being torn in a million directions with responsibilities for being on multiple out of hours committees and the like for whānau as well as a day job and busy homelife."

5.45

We saw examples of two councils using local consultants to support iwi engagement on the iwi's behalf. That might be a useful model, although exactly how it operated would need to be tested with iwi. We also saw examples of council staff working with iwi representatives directly about how they wished to be involved in upcoming climate-related work.

5.46

We encourage all councils to consider the voluntary nature of iwi and hapū engagement and the imbalance of resources, and to work with iwi and hapū to identify modes of engagement that work for all parties.

Relationships are important

5.47

Iwi and hapū representatives consistently raised the importance of mutually respectful relationships. They confirmed that enduring and meaningful relationships are important to effectively engaging iwi and hapū on shared goals for managing the impact of a changing climate.

5.48

We found three dimensions of council–Māori relationships to be particularly worth highlighting.

5.49

For Māori, relationships with the four councils are underpinned by personal connections. That means that effective working relationships can be disrupted by elections that bring in a change of elected members and mayors. The biggest challenge for some is continual change in council staff – effort is put into building relationships over time, only to have to start again when staff move on to other roles.

5.50

All four councils need to consider how to embed relationships with iwi, hapū, and Māori so that connections can be sustained over time, including going beyond the cyclical nature of elections and normal staff turn-over.

5.51

Engagement was seen as positive where there was mutual respect and where it was designed to be mutually beneficial. Mutual respect can be reinforced, for example by council staff investing the time and a genuine willingness to work with iwi and hapū on climate-related issues. It can be undermined by not acknowledging the input that was sought from and provided by iwi and hapū, or a perceived lack of effort to understand and incorporate Māori values.

5.52

We heard examples where councils invited iwi and hapū representatives onto consultative working groups that appeared to be designed to serve primarily council purposes.

5.53

We have noted these themes in our other work, such as in our May 2024 follow-up report on regional councils' freshwater management, which identified the benefits that strong relationships with iwi and hapū can bring to councils' management of natural resources.

5.54

A 2022 report we commissioned, Māori perspectives on public accountability, similarly noted the importance that Māori place on personal relationships over interacting with a system. "Trust … is built with the people inside an organisation rather than the organisation itself."22

15: Ngā Ringaringa Waewae is a community and hapū co-operative, formed in partnership with the hapū collective working on Te Pūwaha, the Whanganui Port revitalisation project.

16: The North Mole is the northern side of the Whanganui River mouth breakwater. Castlecliff is the stretch of coastline just north of the Whanganui River mouth.

17: The NTCF is a community-led climate action initiative. Its aim is to empower the community to take urgent climate action. Nelson City Council signed the NTCF charter as a partner organisation. That obliges the Council to act in good faith within its functions and capabilities to support the NTCF in achieving its goals. Tasman District Council is also a member of the NTCF.

18: Rating districts are specific areas within a council's boundaries that attract targeted rates to fund works or services exclusive to that area.

19: Controller and Auditor-General (2024), Regional councils' relationships with iwi and hapū for freshwater management – a follow-up report, at oag.parliament.nz.

20: Ministry for the Environment (2019), Arotakenga Huringa Āhuarangi: A Framework for the National Climate Change Risk Assessment for Aotearoa New Zealand, page 35, at environment.govt.nz.

21: Controller and Auditor-General (2023), Four initiatives supporting improved outcomes for Māori, page 35, at oag.parliament.nz.

22: Haemata Limited (2022), Māori perspectives on public accountability, page 11, at oag.parliament.nz.