Part 4: Matters we identified during our audits

4.1

In this Part, we set out matters that we identified during the 2021 school audits.

School payroll

4.2

Because salary costs are the largest operational cost of schools, the payroll information is a significant part of the financial statements. The Ministry of Education funded about $6.2 billion (2020: $6 billion) of salary and employee-related costs for the 2021 school payroll year. Education Payroll Limited administers the school payroll on behalf of the Ministry.

4.3

The school payroll audit process includes distributing payroll reports to schools and their auditors, and the appointed auditor of the Ministry of Education (who tests the payroll centrally). This process has improved in recent years. However, a late change to the payroll system in 2021 did affect the 2021 school audits.

4.4

In October 2021, EdPay fully replaced Novopay Online as the system for processing payroll transactions. Novopay Online was subsequently decommissioned. This meant that the Novopay Online transaction report, a report that many schools relied on to check the accuracy of payroll-related changes, would no longer be available.

4.5

Where possible, our auditors rely on an organisation’s controls because this reduces the amount of other testing required. Because of the change to the payroll system, and no access to the Novopay Online transaction report, auditors could not rely on payroll controls for most schools. As a result, our auditors had to carry out additional and unplanned payroll testing for many of the audits. This additional payroll testing contributed to a noticeable delay in audits being completed.

4.6

Initially, schools were not given any guidance on how to check whether payroll changes had been correctly processed without the Novopay Online transaction report. Education Payroll Limited has since released updated guidance on school-level internal controls (in March 2022), including how reporting through EdPay supported these controls. The Ministry and Education Payroll Limited developed the guidance together.

4.7

Various EdPay transaction history reports are now available for schools to check the accuracy of payroll changes. However, because the transaction history reports were not all in place until the end of March 2022, auditors will be unable to rely on payroll controls for the 2022 school audits. Controls need to be operating for the full year for an auditor to rely on them. Therefore, additional payroll testing will be required for many audits for 2022.

4.8

In our report Results of the 2020 school audits we recommended that the Ministry of Education work collaboratively with Education Payroll Limited to ensure that changes to school payroll processes do not adversely affect the control environment of schools. This includes ensuring that schools have controls that prevent fraud and error and that all transactions are approved within delegations. This is included in the guidance released in March 2022.

Findings from our 2021 audits

4.9

Our appointed auditor for the Ministry of Education carries out extensive work on the payroll system centrally. This includes carrying out data analytics of the payroll data to identify anomalies or unusual transactions and testing the payroll error reports that are sent to schools.

4.10

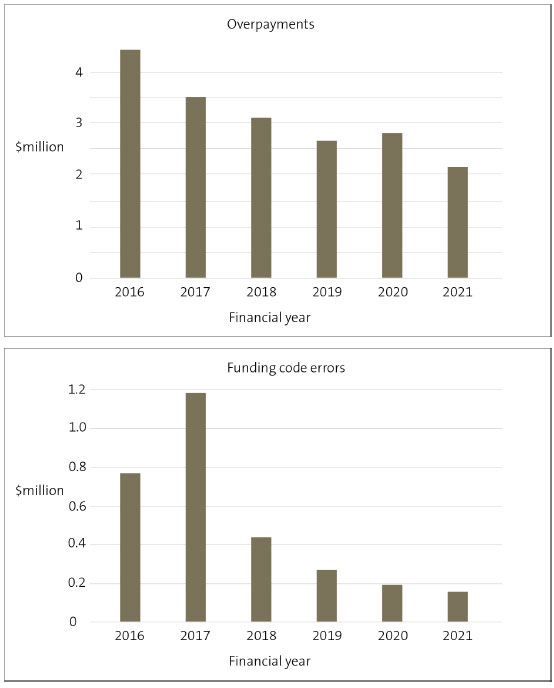

We write to the Ministry of Education every year setting out our findings from this work. We continue to see improvements in data quality – there are fewer errors in the data each year and a reduction in the value of those errors (see Figure 14).

Figure 14

Value of payroll errors, from 2016 to 2021

Source: Education Payroll Services: Results and communications to the sector to support the audits of schools’ 31 December 2021 financial statements.

4.11

Our auditors follow up any anomalies that the data analytics work identifies and that the Ministry of Education cannot resolve. Some anomalies are also sent to Education Payroll Limited to be resolved.

4.12

For the 2021 audits, we identified 1823 exceptions (2020: 1905) for 974 schools (2020: 803) that our auditors needed to follow up on.

4.13

Exceptions are instances that do not follow the normal pattern. Most of the exceptions that auditors followed up were considered valid or reasonable. If exceptions were not valid or reasonable, adjustments were made.

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003

4.14

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003 has arisen because clauses in the Holidays Act or employment agreements might have been incorrectly interpreted when calculating holiday entitlements. As we have previously reported, the Ministry of Education has identified instances of non-compliance for employees on the school payroll.

4.15

The Ministry continues to do work to identify and resolve non-compliance with the Holidays Act, but it has not yet identified the amounts attributable to each employee and how it will affect individual schools.

4.16

Because boards are employers of teachers, they need to recognise a potential liability for this non-compliance with the Holidays Act. However, until further detailed analysis has been completed, the potential effect on any specific individual or school and any associated liability cannot be reasonably estimated. As for previous years, all financial statements of schools disclosed a contingent liability for non-compliance with the Holidays Act.

Cyclical maintenance

4.17

The Ministry of Education (or a proprietor for state-integrated schools) provides schools property. Schools must keep their property in a good state of repair. Schools receive funding for this as part of their operations grant.

4.18

A cyclical maintenance provision is included in the financial statements of schools to account for their obligation to maintain the property. Schools need to plan and provide for future significant maintenance, such as painting their buildings.

4.19

Auditing the cyclical maintenance provision has always been challenging. We have reported on this aspect of the financial statements many times in the past. Many schools do not fully understand the cyclical maintenance provision and do not always have the necessary information to calculate it accurately.

4.20

The 10-year property plans of schools, which are now prepared by property consultants approved by the Ministry of Education, should include maintenance plans that set out how schools should maintain their buildings for the next 10 years. Schools typically use the property plans to calculate their cyclical maintenance provisions.

4.21

Where possible, auditors have previously relied on cyclical maintenance plans that are prepared as part of the 10-year property plans. This is because a Ministry-approved property consultant prepares them. However, recent changes to an international auditing standard means that our auditors need to get more detailed information about how a board has estimated its cyclical maintenance provision. This includes understanding the method, assumptions, and data on which the provision is based.

4.22

This year, we gathered information from our auditors about whether schools had reliable cyclical maintenance plans to support the provisions recorded in their 2021 financial statements. Our auditors told us that about 21% of schools did not have reliable plans.5 We have shared the results of the information we gathered with the Ministry of Education.

4.23

If a school has a maintenance plan prepared by a Ministry-appointed property consultant, auditors can place some reliance on the fact that the plan has been prepared in accordance with the Ministry’s requirements and approved by the Ministry. This reduces the amount of audit work required. However, our auditors find that maintenance plans are not always prepared.

4.24

This is a long-standing issue. In our 2020 report on the school audit results, we repeated our earlier recommendation that the Ministry ensure that schools comply with their property planning requirements by having up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans.

4.25

If a school does not have a maintenance plan, it needs to source other information to calculate a reasonable cyclical maintenance provision. This can be time-consuming for schools and auditors. This year our auditors found that some schools without a maintenance plan struggled to get information, such as painting quotes, to support their cyclical maintenance provision because of the scarcity of suppliers. We have repeated our recommendation from previous years.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education ensure that schools are complying with their property planning requirements by having up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans. This includes reviewing those plans to assess whether they are reasonable and consistent with schools’ asset condition assessments and planned capital works. |

Budgeting

4.26

Section 87(3)(i) of the Education Act 1989 requires each school to disclose budgeted figures for the statement of its revenue and expenses, the statement of its assets and liabilities (balance sheet), and the statement of its cash flows.6 Schools need to include the budget figures from their budget approved at the beginning of the school year.

4.27

Our auditors check that the numbers in the financial statements of schools are from the approved budget. However, our auditors continue to find that many schools do not prepare a budget balance sheet or a budget cash-flow statement.

4.28

Having a full budget, including a balance sheet and statement of cash flows, is a legislative requirement and important for good financial management. Although monitoring the revenue and expenditure of schools is important, so is managing cash flows and ensuring that schools have enough cash to meet their financial obligations when they are due. If schools do not manage this properly, they can get into financial difficulty.

4.29

We asked our auditors to tell us about schools that are not preparing a full budget again this year. Our auditors identified 485 schools (2020: 467) that were not preparing full budgets. Although we have raised this matter in management letters sent to boards, this shows that there has been no improvement since 2020.

4.30

We have shared this information with the Ministry of Education so it can discuss this with individual schools as they prepare their budgets for the next school year.

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education engage with the schools we have identified as not preparing full budgets and provide them with the necessary support to ensure that their budgets for the next school year are complete. |

Sensitive expenditure

4.31

For the 2021 school audits, our auditors brought fewer matters about sensitive expenditure to our attention. However, we referred to sensitive expenditure in some audit reports (see paragraphs 2.37-2.41). If the amount of expenditure involved is less significant, or the matter relates to policies and procedures underlying sensitive expenditure decisions, auditors will raise the matter in the management letter rather than the audit report.

4.32

The matters that auditors raised in management letters in 2021 were similar to previous years. They included:

- schools that did not have sensitive expenditure policies, including for gifts, or the policies were not updated regularly (this applied to six schools);

- gifts to staff that either did not have board approval or were inconsistent with the school’s gift policy (this applied to eight schools);

- hospitality and entertainment expenses that seemed excessive (this applied to 10 schools); and

- travel-related expenditure (this applied to three schools).

4.33

Most of the concerns about school policies and procedures for sensitive expenditure payments were about poor controls over the approval of principals’ expenses or credit card expenditure. The main matters raised were:

- principals approving their own expenses or the spending was not approved by someone more senior (this applied to 35 schools);

- no approval of credit card expenditure or it was not approved by someone more senior than the person incurring the expenditure (this applied to 19 schools);

- inadequate or no documentation to support expenditure (this applied to nine schools); and

- no approval of fuel card statements, travel vouchers, or gift vouchers (this applied to eight schools).

4.34

As we have previously reported, credit cards are susceptible to error and fraud or being used for inappropriate expenditure, such as personal expenditure. Money is spent before any approval is given, which is outside the normal control procedures over expenditure for most schools. This also applies to fuel cards or store cards.

4.35

Our auditors identified three schools where funds had been used for personal use. For two of these instances, the school was reimbursed.

4.36

Schools should use a “one-up” principle when approving expenses, including credit card spending. This means that the presiding member (the chairperson) of a board would need to approve a principal’s expenses. It is also important that credit card users provide supporting receipts for the approver and an explanation for the spending.

4.37

We include guidance about using credit cards in our good practice guide Controlling sensitive expenditure.7 This provides guidance on making decisions on sensitive expenditure, guidance on policies and procedures, and examples of sensitive expenditure.

4.38

We also have other information on sensitive expenditure in the good practice section of our website.

Publishing annual reports

4.39

Schools are required to publish their annual reports online.8 This annual report consists of an analysis of variance,9 a list of board members, financial statements (including the statement of responsibility and audit report), and a statement of KiwiSport funding.

4.40

It is important that schools publish their annual report soon after their audit is completed. This ensures that they comply with legislation and are accountable to their community.

4.41

Our auditors check whether schools have published the previous year’s annual report. If a school does not have a website, the Ministry of Education can publish the annual report on its Education Counts website.

4.42

The number of schools that publish their annual reports online has remained reasonably consistent since 2020. At the time of the 2021 audits, we found that 88% of schools had published their 2020 annual report online (2020: 90% of schools had published their 2019 annual report online).

4.43

Although this consistency is encouraging given the delays in completing audits due to the Covid-19 pandemic, our auditors identified 267 schools that had not published their annual reports online. Parents and other members of a community should be able to access the school’s annual report online.

Ka Ora, Ka Ako healthy school lunches programme

4.44

In 2019, the Government announced a pilot programme, the Ka Ora, Ka Ako healthy school lunches programme, to deliver a free daily lunch to primary and intermediate-aged learners/ākonga in schools in communities with socio-economic barriers.

4.45

In 2020, the Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund expanded the programme to allow eligible schools to either make their own lunches or have an external supplier provide them. If an external supplier is used, the Ministry of Education directly manages the relationship. In 2020, $5.5 million was paid to external providers on behalf of schools. Funding for the programme has been extended until December 2023. In 2021, $142 million was paid to external providers on behalf of schools.

4.46

Although the Ministry of Education directly pays suppliers, it is still the expenditure of the school and must be included in its financial statements. The Ministry provided schools and auditors with details of the amounts to be included in the financial statements of each school. To provide assurance over this information, we carried out audit procedures centrally. However, our auditors still needed to carry out some audit procedures locally to ensure that the payments reflected in the financial statements of each school were correct.

4.47

Our central assurance procedures found some errors in the information the Ministry of Education provided. Our auditors also found that some schools did not have records of how many lunches they had received. This caused delays to some audits. We have discussed this with the Ministry and the Ministry has assured us it has made improvements to its processes for the next year. The central assurance audit of the programme for 2022 will also be carried out at an earlier date.

5: Many of the schools that did not have reliable plans were able to provide other forms evidence to support their cyclical maintenance provision.

6: Section 87(3)(i) of the Education Act 1989 remained in force for the 2021 audits because the section of the Education and Training Act for school planning and reporting did not come into effect until 1 January 2023.

7: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Controlling sensitive expenditure: Guide for public organisations, at oag.parliament.nz.

8: Section 136 of the Education and Training Act.

9: An analysis of variance is a statement where a school board provides an evaluation of the progress it has made in achieving the aims and targets set out in its Charter.