METHODOLOGY

Too often, Māori have not benefitted from research by non-Māori organisations. The impacts of western forms of knowledge and research have even been detrimental to indigenous peoples, including Māori, and, for some, this has led toward a rejection of ‘all theory and all research’. Kaupapa Māori-based research methodology aims to gain back trust through implementing ‘culturally safe’ practices undertaken by Māori researchers grounded in their cultural identity and guided by tikanga (cultural protocols).

Throughout this project, Haemata has held a responsibility both to the Office and to the research participants to uphold principles of cultural safety, integrity, trust, and respect — principles inherent to any Māori-centred research approach. A Māori-centred research design approach also involves ensuring a high level of Māori participation in all aspects of the research methodology, including in key roles such as researchers, advisors, participants, data analysts, report writers and quality assurers. In a Māori-centred research approach, te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, and mātauranga Māori are “givens”.

In this study, kaupapa Māori research principles, as described by Dr Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012)8 have guided the research process, alongside Haemata’s own principles-based approach. These principles are:

- Aroha ki te tangata (a respect for people).

- Kanohi kitea (the seen face; that is, present yourself to people face-to-face).

- Titiro, whakarongo, kōrero (look, listen, speak).

- Manaaki i te tangata (share and host people, be generous).

- Kia tūpato (be cautious).

- Kaua e takahi i te mana o te tangata (do not trample over the mana of the people).

- Kaua e mahaki (do not flaunt your knowledge).

- Mā te Māori (there must be benefits for Māori in undertaking this project).

- Kia ngakau pono, kia mākohakoha, kia manawanui, (work with integrity, an open-mind and commitment).

These principles have underpinned our work throughout this study and have guided our discussion of the findings.

Overview of the Approach

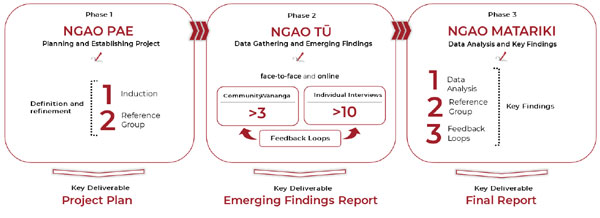

The study involved three phases: Ngao Pae (Planning and Establishing Project), Ngao Tū (Data Gathering and Emerging Findings) and Ngao Matariki (Data Analysis and Key Findings).

Figure 1: Three-phased approach to the research.

Te Ohu Whāiti

Te Ohu Whāiti was established during the planning phase of the project as a reference group to provide oversight and ongoing guidance to the project team. Te Ohu Whāiti was an important verification mechanism in the methodology, to substantiate the methodology and interpretation of the findings.

Members of Te Ohu Whāiti included:

- Ria Earp (Māori community, public sector).

- Dr Mere Skerrett (Māori community, academic).

- Luke Crawford (Māori community, kaumātua).

- Leeanne McAviney (Assistant Auditor-General, Sector Performance, Office of the Auditor-General).

- Greg Schollum (Deputy Controller and Auditor-General, Office of the Auditor-General).

Te Ohu Whāiti meetings were attended and facilitated by members of the Haemata research team, with the lead researcher facilitating the meetings.

The role of Te Ohu Whāiti as defined in the Terms of Reference included contributing to any matter relating to the scope of the research, ethical guidelines, research design, methodology, data analysis and implications.

Fieldwork

The fieldwork phase of the study, Ngao Tū, utilised two key data gathering approaches – wānanga and interviews. Given the restrictions of undertaking the study in a COVID-19 environment, online platforms (namely Zoom and Microsoft Teams) were the primary channels of connection with participants and communities.

Each wānanga was supported by a video recording of the Auditor-General and Deputy Auditor-General discussing the role of the Office. A presentation with guiding questions and discussion points also supported the delivery of wānanga. Because online wānanga were necessarily more intensive than may have otherwise been possible in a face-to-face setting, Jamboards9 (interactive digital whiteboards) were utilised as a data gathering tool, allowing participants who wanted more time to think through their responses, or who preferred to contribute ideas in written form, to do so. This maintained our commitment to a kaupapa Māori research approach by respecting the right of participants to determine how they want to engage, and providing multiple options for that engagement. Access to the Jamboards was available post-wānanga for those participants who wanted to continue contributing views after the face-to-face discussion, and some took up that opportunity.

Interviews took a semi-structured format and were used to delve deeply into an interviewee’s perspectives as well as ‘test’ ideas and issues emerging from wānanga.

A semi-structured approach to the fieldwork was purposely applied to enable participants the ability to shape the direction of the discussion, and to share what was most important to them. This contrasts with other more structured research approaches (e.g., surveys and structured interviews) which position the control in the hands of the researcher and deny participants the opportunity to influence the research and have their true voices heard. Arguably, such approaches are also contrary to Māori-centred research principles.

Wānanga as a Research Approach

Wānanga as a research approach to data gathering provides a format for open and honest discussion embedded in Māori cultural practices. Central to wānanga are values of whanaungatanga (relationships), mihimihi (acknowledgements), discussion (kōrero), and ako (learning). Whare wānanga (universities or places of higher learning) as we know them today are derived from this cultural mechanism for discussion and learning. But as Nēpia and Rangimārie Mahuika offer, ‘wānanga are much more than just schools of instruction’.10 Wānanga are a dynamic living tradition that has developed across generations.

Prevalent in our pūrākau (cultural narratives), there are several different claims of the ‘first-ever wānanga’. One account identifies Rangiātea as the first wānanga – ‘a building in the 12th heaven where the baskets of knowledge were suspended and gifted to Tāne’. Another account describes the first wānanga as an event held by the children of Ranginui (Sky father) and Papatūānuku (Earth mother). Trapped in the darkness of their parents’ embrace, the offspring of Ranginui and Papatūānuku gathered to debate a solution that culminated in the first whānau (family) community governance meeting in the Māori world and the separation of the earth from the sky.11 Mātangireia is recognised as the original ‘Whare Wānanga’ (place of learning and wānanga), and the foundation from which subsequent traditional whare wānanga were built, and from whence came all knowledge.12

In a contemporary sense, the practice of wānanga involves engaging in active and collective thinking and problem solving to create new understanding and knowledge.

Participants

In total, 69 individuals were invited to participate in the study of which nearly 50% (35) were available and contributed to the findings.

Three separate wānanga were convened, each with a different group of key stakeholders:

- Wānanga 1 — Māori public servants in government agencies recently audited by the Office of the Auditor-General.

- Wānanga 2 — Māori service providers and Iwi who deal with government contracts and have had experience being audited by the Office.

- Wānanga 3 — Whānau members who interact with public services directly or indirectly.

With the support of Te Ohu Whāiti, ten individuals who have a keen interest in public accountability were identified as interviewees. Individuals approached for interviews included:

- Members of organisations that the Office audits (e.g., local government, government departments).

- Members of the accountability system (e.g., auditors).

- Commentators on public sector accountability (e.g., academics, iwi chairs).

- Māori community representatives (e.g., iwi and hapū leaders, whānau, rangatahi).

Table 1 Number of participants by type of participation

| Type of participation | # Invitees | # Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Interview | 13 | 10 |

| Wānanga 1: Public servants | 23 | 11 |

| Wānanga 2: Māori service providers and iwi | 17 | 6 |

| Wānanga 3: Whānau and service users | 16 | 8 |

| Total | 69 | 35 |

Feedback Loops

Feedback loops were incorporated into the fieldwork process as a further verification and validation mechanism. All participants received a draft copy of the notes for the wānanga or interview that they participated in, with an invitation to correct, amend, clarify or add to any of the points captured. The intention of building this step into the data gathering process is to ensure that participants are comfortable with the way in which their data is captured and interpreted, and that the interpretation is a true, fair, and accurate representation of their views.

8: Smith, L.T. (1999). Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books, New York, and Otago University Press, Dunedin.

9: Google Workspace. n.d. Jamboard. www.workspace.google.com/products/jamboard

10: Mahuika, N., Mahuika, R. (2020). Wānanga as a Research Methodology. Pp 1-2.

11: Ibid.

12: Ibid.