Part 4: Matters we identified during our audits

4.1

In this Part, we set out matters that we identified during the 2019 school audits and make some recommendations for the Ministry.

Publishing annual reports

4.2

Schools are required to publish their annual reports online.8 A school’s annual report consists of an analysis of variance9, a list of trustees, financial statements (including the statement of responsibility and audit report), and a statement of KiwiSport funding.

4.3

Last year we found that a large proportion of schools had not published their 2017 annual reports. Of those that had published their annual report, many had done so only after being reminded by the auditor. It is important that schools publish their annual report as soon as possible after the school’s audit is completed. This ensures that schools do not breach legislation and are accountable to their community.

4.4

At the time of this year’s audits, we found that 1755 or 82%10 of schools had published their 2018 annual report on their website. This is a significant improvement on the previous year, when only 68% had published their 2017 annual report. We and the Ministry encourage schools to publish their annual reports as soon as the audit is completed.

4.5

If a school does not have a website, the Ministry will publish the annual report on its Education Counts website. We encourage parents and other members of the school’s community to contact the school board if the school’s annual report has not been published online.

School payroll

4.6

The school payroll information is a significant part of a school’s financial statements. After Novopay was introduced, the additional payroll reports that schools needed to complete their financial statements contributed to delays in the school audits. However, we have worked with the Ministry in recent years to ensure that this information is provided in a timely manner.

4.7

The agreed time frames for providing payroll information to the school sector and the auditors for the 2019 audits were met and, as shown in Figure 2, our auditors started receiving draft financial statements earlier than in recent years. Unfortunately, this was overshadowed by the disruptions caused by Covid-19, but it is encouraging for future audit years. We will work to the same time frame for the 2020 school audits.

4.8

Our auditor of the Ministry carries out extensive work on the Novopay system centrally. This includes carrying out data analytics of the payroll data to identify anomalies or unusual transactions and testing the payroll error reports that are sent to schools. We write to the Ministry every year setting out our findings from this work. We continue to see improvements in data quality and fewer errors being raised on school error reports (see Figure 11).

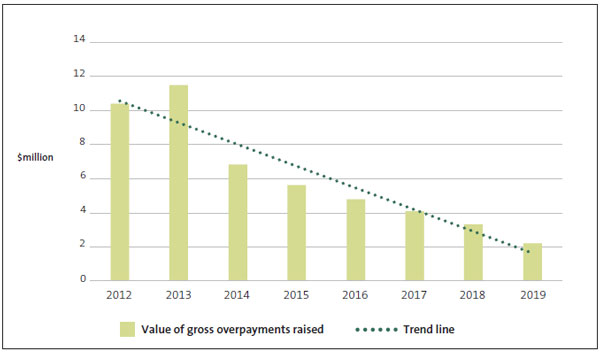

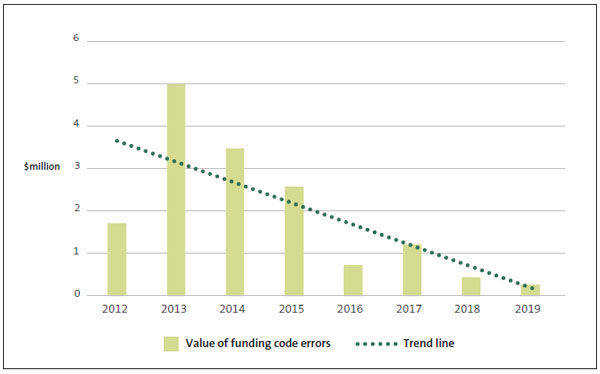

Figure 11

Value of payroll errors, 2012 to 2019

The graphs show the reduction in overpayments and funding code errors by value recorded from 2012 to 2019. Novopay was introduced in August 2012, which meant that 2013 was the first full year using the system. Since then, both the number and value of errors have decreased. Funding code errors are those where payroll payments have been incorrectly funded by either the board or the Ministry. These result in an amount either owed to, or owed by, the school.

Source: Education Payroll Services: Results and communications to the sector to support the audits of schools 31 December 2019 financial statements.

4.9

As part of their audit work locally, our auditors follow up any anomalies identified from the data analytics work that the Ministry cannot resolve. Some anomalies are also sent to the pay centre to be resolved. We have seen the extent of the exceptions sent to schools decrease over the years, but some matters reoccur. For the 2019 audits, we identified 2086 exceptions for 922 schools that needed to be followed up by school auditors.

4.10

For the 2019 audits, in response to our recommendation, the Ministry built a feedback loop into the process. This allows schools, the pay centre, and school auditors to report what they found from looking into exceptions back to the Ministry. The Ministry can then consider whether additional guidance is required for specific schools or for the sector more widely. The Ministry found that the response rates were low and there were limitations to the information provided. This process will be revisited for the 2020 audits and therefore we have repeated the recommendation below.

4.11

A project is under way to make the school payroll system easier to use for schools by replacing Novopay online with a new portal EdPay. This will allow more data entry directly at schools. The EdPay functions are being rolled out in stages after being tested by a small group of schools. This means that most schools are using a combination of EdPay, Novopay online, and the EPL pay centre to process payroll instructions. Although EdPay will build in some validation checks, which will reduce the number of errors or inappropriate transactions, the controls locally at schools will remain the same. The review of fortnightly payroll reports carried out by the school continues to be the main control that schools rely on to detect errors.

4.12

Although schools are responsible for ensuring the accuracy of their payroll, the current payroll reports are difficult to understand and review. We also identify every year that a number of schools are not adequately reviewing them. This could result in schools paying employees the wrong amount and increases the risk of fraud. It is also important that there is a review of the payroll reports by someone independent of the payroll process – that is, someone without access to Novopay. In small schools where the principal has access to Novopay, this might have to be done by a member of the school board. It is important that school boards have some oversight of the school’s monthly payroll expenditure, as they do with other expenses.

4.13

We are aware that Education Payroll Limited is currently working on identifying and mapping its controls. It is important that consideration of the controls in the payroll system include consideration of all parties involved. We therefore continue to urge the Ministry to ensure that appropriate internal controls are incorporated into the payroll system, where possible, to make it easy for schools to operate appropriate controls to help prevent instances of fraud or error, and repeat our previous recommendation below.

| Recommendation 1 We recommend that the Ministry of Education ensure that changes to the Novopay system include adding appropriate controls for schools, where possible, to help prevent fraud and error and ensure that all transactions are approved within the school’s delegations. |

| Recommendation 2 We recommend that the Ministry of Education follow up unusual transactions and anomalies identified as part of the payroll audit so they do not reoccur, including giving boards additional support and guidance on payroll matters if necessary. |

Sensitive payments

4.14

We refer to some sensitive payments in Part 2, where we considered them significant enough to mention in the school’s audit report. If an auditor does not consider a matter significant enough, or it relates mainly to school policies and procedures, the auditor will raise the matter in the school’s management letter. This year, auditors brought fewer matters about sensitive payments to our attention, but our auditors continue to refer to such matters in their management letters to school boards.

4.15

Concerns that auditors raised included:

- schools that did not have sensitive expenditure policies;

- gifts to staff that were either without board approval or inconsistent with the school’s gift policy;

- hospitality and entertainment expenses that seemed excessive; and

- travel, both domestic and international, where the boards have not followed a clear process of approval before the trip was booked.

4.16

Our auditors also identified payments for items that could be seen to bestow a personal benefit, such as gym and Koru Club memberships for principals. Under the Principals’ Collective Agreement, any additional benefit requires Ministry approval, so if schools make such payments they need to consider whether in doing so they are breaching the collective agreement. The Ministry’s circular states that the school does have some discretion on such sensitive payments, but they must have a business purpose and provide only an incidental private benefit to the principal. The Ministry has told us it is updating the circular to provide more guidance to schools on what is considered to be incidental private benefit.

4.17

Almost half of the concerns raised about sensitive payments related to poor controls over the approval of principals’ expenses. The main matters raised were:

- principals approving their own expenses;

- expenses being approved by other staff members;

- expenses being approved outside agreed delegations; and

- inadequate or no documentation to support expenditure.

4.18

Of the concerns raised, half related specifically to the use of credit cards. As we reported last year, credit cards are susceptible to error and fraud or to being used for inappropriate expenditure, such as personal expenditure. Credit card payments might not go through a school’s normal payment processes because schools often pay credit card balances directly from their bank account. Additionally, the money is spent before any approval. However, it is important that expenditure on credit cards is subject to the same controls as other spending.

4.19

We remind schools that they should use a “one-up” principle when approving expenses, including credit card spending. This means the board chairperson would need to approve the principal’s expenses. It is also important that credit card users provide supporting receipts for the approver and an explanation for the expenditure. This also applies to fuel cards or store cards.

4.20

We have recently updated our good practice guide on controlling sensitive expenditure, which is available on our website. This includes information about the use of credit cards.

Overseas travel

4.21

After the updated Ministry guidance in 2017 and the requirement for schools to disclose any significant overseas travel in their financial statements, we have had fewer concerns raised with us about spending on overseas travel. We did draw attention to spending on overseas trips in two audit reports (as set out in Part 2 of this report), but these were both 2017 audits.

4.22

We continue to see the use of preloaded foreign currency cards for use abroad. However, when using this type of card, schools need to consider who issues the card and be mindful of the rules in the Education and Training Act about banking and investments. The Act allows schools to hold funds only in New Zealand dollars and in banks with a certain credit rating. Depending on the terms and conditions underlying the use of the card, schools need to consider whether putting funds on a foreign currency card could put those funds at risk.

4.23

Covid-19 has prevented many overseas trips from going ahead during 2020. We have had concerns raised with us about the management of refunds for these trips, and in particular how fundraising monies for these trips should be managed.

4.24

In our view, how funds collected specifically for overseas trips should be managed is dependent on the source of the funds:

- Funds parents paid directly to the school as a contribution to the trip can be refunded to those parents, to the extent that the school has received refunds for any costs already incurred.

- Funds raised from fundraising activities carried out in the name of the school cannot be repaid to individuals, because they are funds raised for the trip rather than for the individual participants.

4.25

A school raising funds for a specific purpose should “in good faith” use those funds for the purpose for which they were given. If the school is unable to spend the funds on the stated purpose (as is the case currently for funds raised for overseas trips), our expectation would be that, where possible, the school spends the funds in a way that is consistent with the original reason for raising the funds. If the school considers that the uncertainties of Covid-19 would make it not practical to carry forward the funds for future overseas trips, the school needs to consider alternative uses that would be acceptable to those who gave the funds.

Fraud

4.26

We collect information every year about fraud or suspected fraud in schools that our auditors are told about as part of their audits. We report fraud trends on our website each year. This includes details of the methods and reasons for fraud, types of fraud, and how the fraud was detected.

4.27

Many incidences are relatively minor, such as the theft of small amounts of cash or equipment, or misuse of credit or debit cards. However, there have been several more significant frauds in the past few years, which often involve fraudulent payments. These thefts are carried out mainly through using false invoices – for example, employees with delegated authority entering false or overstated invoices for payment. We have seen an increase in cybercrime, and this has been an increasing threat since Covid-19.

4.28

For individuals to be motivated to commit fraud, it is considered that three elements must come together:

- Motivation – a perceived pressure, either financial or emotional, pushing a person towards fraud.

- Opportunity – the ability to execute the fraud without being caught.

- Rationalisation – a personal justification for the dishonest actions.

4.29

Motivation and rationalisation are usually personal to an individual and employers are unlikely to be able to affect or control these. However, because opportunity refers to the circumstances that allow fraud to occur, this is something employers can control. Circumstances that provide opportunities for committing fraud might include:

- weak internal controls, which an employee is able to circumvent; or

- poor “tone at the top” being the board’s and senior management’s commitment towards acting with integrity.

4.30

One of the best ways for an entity to mitigate against fraud is to ensure that adequate internal controls are in place. We recommend that schools:

- ensure that they have good segregation of duties (needing more than one person to complete a task);

- encourage electronic payment for fees or large invoices, rather than cash payments;

- obtain and review supporting documentation before payments are made, which should then be marked as paid;

- require a second person to review and authorise all changes to supplier details;

- verify changes to supplier bank accounts directly with the supplier; and

- investigate all suspicious invoices.

4.31

We understand that schools, particularly small schools, can find it difficult to segregate duties because they have few administration staff. However, where this is the case, the school needs to consider what mitigating controls it can put in place. This could be through additional monitoring by management or the board.

4.32

Cybercrime continues to affect public entities. Common cybercrime threats include compromising an employee’s email account and phishing scams (where employees are tricked into giving up log-in details or they allow ransomware to be loaded onto the network). We have also seen instances in the public sector where employees are tricked into paying an invoice outside the entity’s usual processes. This type of fraud can happen when organisations:

- override their existing controls;

- have a lack of controls for changes to supplier details;

- have not adequately assessed, or understood, the risks of cybercrime; and

- do not have an adequate cyber-incident response plan.

4.33

There is evidence that entities are less susceptible to fraud when they provide specific training for all employees, and employees are aware of fraud policies and see them in action. This is because employees will be more alert to, and more aware of, fraud risks and will know what to do if they suspect fraud.

4.34

Boards should have a fraud policy in place. A fraud policy should contain the entity’s position on reporting actual or suspected fraud to the appropriate law enforcement authority. However, a fraud policy is effective only if the board communicates this to its staff regularly and acts on it when a potential fraud is identified. The Ministry has published a model policy on Theft and Fraud Prevention in its Model Financial Policies.

4.35

In previous reports, we recommended that the Ministry improve its guidance on internal controls and fraud. The Ministry told us it is reviewing its guidance to schools on internal controls and developing tools to assist boards to assess their systems of internal controls. We have repeated the recommendation below.

| Recommendation 3 We recommend that the Ministry of Education improve its guidance to schools on what good controls look like. |

Conflicts of interest

4.36

As noted in Part 2, this year we identified an increase in the number of breaches of legislation about conflicts of interest. Two instances were where schools entered into contracts that totalled more than $25,000 with organisations in which a trustee had an interest. This is not allowable unless the trustee obtains Ministry approval.11

4.37

The risk of conflicts of interest in small communities, which many schools operate in, is inherently high, because the board, principal, and other employees are often living and interacting in the same communities their school services. There is a particular risk of conflict in the decision-making processes used to appoint new employees and contractors, as well as the purchase of goods and services. The small size of some schools can make the segregation of duties, which might otherwise prevent conflicts arising, difficult to achieve.

4.38

In June 2020, we published updated good practice guidance: Managing conflicts of interest: A guide for the public sector. We are looking to raise the profile of conflict of interest management more generally and have created an interactive quiz, covering a range of scenarios where interests might conflict.

4.39

The other conflicts of interest identified from our audits related to more than one member of staff being on the board of trustees. A permanent member of staff is excluded from being on the board unless they are the principal or the staff representative.

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003

4.40

The issue of non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003 has arisen because entities might have incorrectly interpreted clauses of the Act or employment agreements when calculating holiday entitlements. As previously reported, the Ministry has identified that there is an issue with holiday pay for employees on the school payroll.

4.41

This year, the Ministry has continued its work on identifying and resolving the non-compliance with the Holidays Act. It has not yet been able to identify the amounts attributable to each employee.

4.42

Because school boards are the employer of all teachers, they need to recognise a potential liability for this non-compliance with the Holidays Act. However, until further detailed analysis has been completed, the potential effect on any specific individual or school and any associated liability cannot be reasonably estimated. For 2019, as for 2018, all school financial statements disclosed a contingent liability for non-compliance with the Act.

Following up on previous years’ recommendations

4.43

The Ministry has made good progress on many of the recommendations from our previous reports. We comment on some of those matters below. The Appendix updates progress on all our previous recommendations.

Incomplete school budgets

4.44

Schools are required to disclose budgeted figures for the statement of their revenue and expenses, the statement of their assets and liabilities (balance sheet), and the statement of their cash flows.12 Our auditors are still finding that many schools are not preparing a budget balance sheet or a budget cash flow statement.

4.45

Schools need to include their approved budget figures in their financial statements. Auditors will check that the figures included in the school’s financial statements are those from the approved budget. This information is required by legislation. If schools do not disclose these figures, they are breaching legislation.

4.46

In last year’s report, we asked the Ministry to provide more guidance to schools on proper budgeting. It has done so, including identifying this as an area for improvement in its Annual Reporting Circular and Annual Reporting webinar. For the 2020 school audits, we will be collecting information on those schools that are not preparing a full budget and sharing it with the Ministry.

Accounting for “other activities”

4.47

We raised concerns in our report on the results of the 2017 school audits about the accounting arrangements for “other activities” carried out by schools. A number of these activities are carried out on behalf of a number of schools, and are referred to as cluster arrangements. One school is considered to be a “lead school” and is responsible for the receipt of the funding and, if applicable, employing the teachers. The most common of these arrangements include clusters for Resource Teachers of Learning and Behaviour (RTLB), activity centres, and Resource Teachers of Literacy RTLit).

4.48

How these arrangements are accounted for by the schools is determined by the governance arrangements, which are usually set out in a Memorandum of Agreement between the schools. This determines whether the school is working as an “agent” in administering the funds or whether the board is in a governance position and the activity is therefore a function of the school. If it is a function of the school, it must record the revenue and expenditure in its financial statements. An example of this is a Teen Parent Unit.

4.49

The most significant of these clusters are RTLBs. These received about $97 million of funding in 2019. The lead school of a cluster includes a note on its financial statements setting out the RTLB funding it has received and how it has been spent. Although this is audited as part of the school financial statements, the depth of audit work and testing will vary depending on its significance to the school.

4.50

We have identified the following matters related to these clusters:

- The current note disclosure sets out the funding and how it has been spent. We are aware of some RTLB clusters that have used funding to purchase assets. These are currently not recorded on any school’s balance sheet.

- We have found instances where there is no signed Memorandum of Understanding, so the governance arrangements are not clear.

- There is some confusion with the schools about our role in auditing the information. In particular, the guidance to RTLB lead schools refers to the RTLB being audited as part of the school’s audit. As noted above, we do not carry out an audit of the RTLB.

4.51

We have asked the Ministry to consider whether the current accountability arrangements for RTLBs are adequate. We also understand that the new Learning Co-ordinators work with several schools and many schools are working together as part of a Community of Learning. It is important that where new arrangements are put in place, the accounting implications are considered and appropriate guidance is provided to schools. We repeat our previous recommendation.

| Recommendation 4 We recommend that the Ministry of Education provide guidance to schools on accounting for “other activities” (including Resource Teacher: Learning & Behaviour clusters) that they receive funding for. |

8: The requirement is Section 136 of the Education and Training Act 2020 (previously Section 87AB of the Education Act 1989).

9: An analysis of variance is a statement in which a school board provides an evaluation of progress made in achieving the aims and targets set out in its Charter.

10: 82% of schools that had completed their audits by 31 October 2020.

11: Sections 9 and 10 of the Education and Training Act 2020 – previously section 103 of the Education Act.

12: See section 87(3)(i) of the Education Act.