Part 3: Schools in financial difficulty

3.1

In this Part, we report on the financial health of schools, those schools considered to be in financial difficulty, and why schools get into financial difficulty.

3.2

The data provided in this Part is based on the financial information collected by the Ministry as at 14 October. At this time, the Ministry’s database had financial information for 2020 schools.

What we mean by financial difficulty

3.3

Most schools are financially sound. However, each year, we identify some schools that we consider to be in financial difficulty.

3.4

When we issue our audit report we are required to consider whether the school can continue as a “going concern’” for the next 12 months. This means that the school has sufficient resources to continue to pay its bills for the next 12 months.

3.5

When carrying out our “going concern” assessment we look for indicators of financial difficulty. One such indicator is when a school has a “working capital deficit”. This means that, at that point in time, the school needs to pay out more funds in the next 12 months than it has available. Although a school will receive further funding in that period, a school might find it difficult to pay bills as they fall due, depending on the timing of that funding.

3.6

A school with an overdraft or low levels of available cash is another sign of potential financial difficulty. As we are considering the 12-month period from the signing of the audit report, we will also consider the school’s performance and any relevant matters in the period since the year end.

The financial health of schools

3.7

At 31 December 2019, the average cash balances5 of all schools was about $287,700 (2018: $281,800). Individual school balances ranged from owing cash of $65,800 to having cash of $6.8 million (2018: owing cash of $20,500 to having cash of $7.1 million). Schools held an average of about $354,300 (2018: $339,200) of investments in longer-term deposits, the maximum being $10.6 million. However, almost a third of schools had no investments.

3.8

When reviewing a school’s financial position, it is important to consider a school’s available cash. By looking at this we can determine whether a school is in a position to continue paying its bills when they are due.

3.9

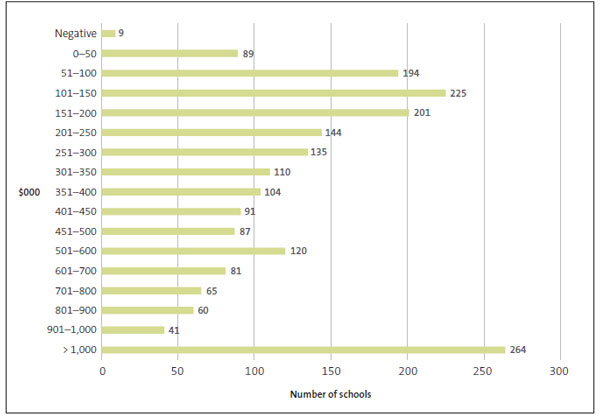

Schools often hold funds on behalf of third parties, including the Ministry for capital projects the school is managing, payments collected from international students for homestay providers, or on behalf of other schools in “cluster”-type arrangements, such as transport networks. If funds held for third parties are excluded, the average cash and investment balances of schools were $568,700. Individual schools range from owing $49,300 to having $10.7 million. Figure 5 shows the levels of school-owned cash and investments held by schools.

Figure 5

Levels of school-owned cash and investments held by schools

The graph shows the number of schools with different levels of school-owned cash and investments. About 5% of schools have school-owned cash and investments of less than $50,000, with nine of these schools having negative balances. Another 10% of schools have balances between $51,000 and $100,000.

Source: The Ministry of Education’s school financial information database.

3.10

As well as cash held for others, cash and investments might be earmarked for a particular purpose, such as a future building project or school trip, or the school might have outstanding bills. This is why we also consider a school’s working capital position (its available funds less the amounts due in the next 12 months) when considering whether a school is in financial difficulty.

3.11

In considering the seriousness of the financial difficulty, we usually look at the size of a school’s working capital deficit against its operations grant. Although many schools receive additional revenue, this is often through donations, fundraising, or other locally sourced revenue, so it is discretionary. For most schools, the operations grant is the only guaranteed source of income.

3.12

At 31 December 2019, we identified 85 (2018: 88) schools with a working capital deficit. Of these:

- 53 (2018: 55) schools had a working capital deficit between 0% and 10% of the operations grant;

- 20 (2018: 22) schools had a working capital deficit between 10% and 20% of the operations grant; and

- 12 (2018: 11) schools had a working capital deficit more than 20% of the operations grant.

3.13

Figure 6 shows that decile rating does not affect whether schools are in financial difficulty. It also shows relatively similar results between years, with the higher decile schools (decile 6 and above) showing small increases in schools with working capital deficits in 2019.

Figure 6

Schools with working capital deficits at 31 December 2019, by decile

There are 85 schools with working capital deficits across all deciles. There are 12 schools with working capital deficits greater than 20% of their operations grant, which could indicate serious financial difficulty.

| Schools with working capital deficits at 31 December 2019 (2018 figures in brackets) |

Schools with working capital deficits greater than 20% of operations grant | |

|---|---|---|

| Decile 1 | 9 (9) | 1 (2) |

| Decile 2 | 10 (14) | 2 (2) |

| Decile 3 | 9 (10) | 3 (0) |

| Decile 4 | 4 (5) | 0 (2) |

| Decile 5 | 6 (11) | 1 (2) |

| Decile 6 | 11 (9) | 3 (1) |

| Decile 7 | 9 (4) | 1 (0) |

| Decile 8 | 12 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Decile 9 | 5 (8) | 0 (1) |

| Decile 10 | 10 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Total | 85 (88) | 12 (11) |

Source: The Ministry of Education’s school financial information database.

The effect of Covid-19 on school finances

3.14

As part of our audit, we need to consider subsequent events (see paragraph 2.2). As explained in Part 2, Covid-19 was a significant subsequent event. Because this did not affect the transactions or financial position recorded by the school as at 31 December, no adjustments were needed to school financial statements. However, auditors did need to consider the effect of Covid-19 and the associated disruptions on the school to determine whether it would affect their audit opinion. This included whether it would change the auditor’s view of the ability of the school to meet its obligations.

3.15

Although schools were closed during Alert Level 4 – and many remained closed once the country moved to Alert Level 3 – the Ministry continued to fund schools. It also provided additional Covid-19-related funding. As a result, we concluded that most schools would not be adversely affected financially by Covid-19.

3.16

For schools that usually raise a lot of their revenue locally through donations, fundraising, and international students, we expected to see a significant reduction in revenue. With the closure of the borders, some international students were not able to travel to New Zealand and many that had arrived went home early. The changes in alert levels also made it difficult for schools to organise and hold many of the activities that they usually carry out to raise funds.

3.17

The ability of schools to manage a significant drop in revenue depends on their financial situation. However, schools did receive some additional funding in 2020, which would have mitigated against some of the loss of revenue. $20 million of international student transition funding was provided to those schools with international students. This was also the first year of the Donations Scheme, which gave decile 1 to 7 schools an additional $150 per student if they did not request donations. We discuss these further in paragraphs 3.37 and 3.40.

3.18

We take all these factors into account when considering whether the school is, or could be, in financial difficulty. However, the international student transition funding was not announced until the end of July when many of our audits would already have been completed.

Schools considered to be in serious financial difficulty

3.19

When we have assessed that a school is in financial difficulty, we ask the Ministry whether it will continue to support the school. If the Ministry confirms that it will continue to support the school, the school can complete its financial statements as a “going concern”. This means that the school can continue to operate and meet its financial obligations in the near future. If we consider a school’s financial difficulty to be serious, we draw attention to it in the school’s audit report.

3.20

Figure 7 shows 38 schools needed letters of support from the Ministry to confirm that they were a “going concern” for the 2019 school audits (2018: 36 schools). We referred to serious financial difficulty in 18 of those schools’ audit reports.

3.21

Te Ra School, an integrated school, received a letter of support from its proprietor. The proprietor agreed to provide financial support to the school. We drew attention to this in our audit report.

Figure 7

Schools that needed letters of support in 2019 to confirm they were a “going concern”

Of the 38 schools that needed a letter of support from the Ministry to confirm they were a “going concern”, nine schools also had a letter of support in 2018, and seven schools needed a letter of support in 2018 and earlier.

| Schools that needed a letter of support in 2019 | Schools that needed a letter of support in 2019 and 2018 | Schools that needed a letter of support in 2019, 2018, and earlier |

|---|---|---|

| Centennial Park School | Bathgate Park School | Albany Junior High School |

| Dalefield School | Burnside Primary School | Cambridge East School |

| Greerton Village School | Green Island School | Kadimah School |

| Howick College | Halfway Bush School | Mangere Bridge School |

| Kaihu Valley School | Nelson College | Omanaia School |

| Kaikorai Valley College | Ōhoka School | Tai Tapu School |

| Kavanagh College | Our Lady Star of the Sea School (Christchurch) | Waitaki Boys’ High School |

| Kerikeri High School | Pukemiro School | |

| Logan Park High School | Westown School | |

| Mercury Bay Area School | ||

| Meremere School | ||

| Nelson Christian Academy | ||

| Northcote College | ||

| Ponsonby Primary School | ||

| Rangikura School | ||

| Raphael House Rudolf Steiner Area School | ||

| Taranaki Diocesan School (Stratford) | ||

| Tauhara Primary School | ||

| Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngati Ruanui | ||

| View Hill School | ||

| Wairau Intermediate | ||

| Waitara Central School |

Source: Information taken from school financial statements and the Office of the Auditor-General’s audit reports.

3.22

We also identified that Nelson College and Pukemiro School for the 2018 year, and Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Rawhiti Roa for the 2017 year, needed letters of support from the Ministry for previous year audits completed since we last reported.

3.23

The number of schools in financial difficulty remains about the same each year (about 40 schools), but they are not always the same schools. Of those schools identified in our report last year, only 14 required a letter of support again this year, with seven needing a letter of support for the past three years or more. Of the remainder, 16 are no longer considered to be in financial difficulty, and the audits of four of the schools are not yet complete.

3.24

The potential effects of Covid-19 did not result in significantly more schools being considered to be in financial difficulty. However, this might be different when we complete our 2020 school audits.

Why do schools get into financial difficulty?

3.25

Many schools rely on raising funds locally to provide additional funding. In 2019, schools received a total of $499 million of locally raised funds (excluding revenue from international students and hostels). These funds can be from donations, grants, parent contributions for curriculum recoveries or activities, trading revenue, fundraising, and other revenue such as rent for school houses and revenue from use of the school hall. In most cases, these types of revenue are discretionary. Parents and others can choose whether to give donations to the school or support their fundraising efforts.

3.26

Some schools also raise funds from international students and hostels – a total of $153 million and $33 million, respectively, in 2019.

3.27

For most schools, it can be difficult to suddenly reduce spending if funds that the school is expecting do not eventuate. This is particularly the case when the funding is used for staffing or other expenditure to which the school is already committed. A reduction in funding can occur if the school has a sudden drop in the number of children attending a school (school roll), or because it is unable to raise funds locally, as has been the case this year due to the restrictions brought about by Covid-19.

Staffing levels

3.28

Each school is given an entitlement of teachers that the Ministry will fund. The entitlement is based on the size of the school roll. If a school has more teachers than its allocation, it has to either pay them directly from its own funds, or it will exceed its staffing entitlement and have to repay the Ministry for the additional staffing costs incurred. The amount of overuse is recovered from the operations grant the school receives in the following years.

3.29

Schools might get into financial difficulty if they do not actively monitor their staffing entitlements or employ teachers in excess of their entitlement. This can happen if the school’s roll has dropped and the school does not reduce the number of teachers accordingly. This might be a conscious decision by the school board, which could choose to keep staff on because they expect that the school roll will increase again. However, if the decision to overstaff is maintained for too long this might affect the financial sustainability of the school.

3.30

All schools pay non-teaching staff from their operations grant. Schools can also choose to use their operations grant and other funding for additional teachers. As explained above, a school operations grant is its only guaranteed source of funding. If a school uses a large percentage of its operations grant to pay staff, it will need other sources of funding to meet its other operational costs. When schools are unable to generate revenue from other sources as they anticipate, they might have to spend their cash reserves or find themselves in financial difficulty.

3.31

More than two-thirds of the schools we identified as being in financial difficulty for 2019 use the equivalent of more than 70% of their operations grant to pay staff (overall, an average of 89%). This was higher than the average for all schools that use the equivalent of 68% of their operations grant to pay staff.

3.32

Figure 8 shows salaries funded by schools as a percentage of their operations grant, by decile. The results are similar for all deciles. However, deciles 9 and 10 have more schools funding salaries that are equivalent to more than 100% of their operations grant. Two-thirds of these schools are funding salaries equivalent to up to 120% of their operations grant.

Figure 8

Payments to board-funded staff as a percentage of the school’s operations grant, by decile

The table shows the percentage schools in each decile use their operations grant to fund staffing costs. The percentage reflects the payments for board-funded staff in relation to the schools’ operations grant. The table shows the number of schools in each category.

| Percentage of operations grant schools use to pay staff | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decile | 0-19% | 20-39% | 40-59% | 60-79% | 80-99% | 100% + | Number of schools |

| Decile 1 | 1 | 21 | 80 | 67 | 20 | 6 | 195 |

| Decile 2 | 2 | 20 | 74 | 72 | 21 | 6 | 195 |

| Decile 3 | 4 | 14 | 72 | 76 | 26 | 13 | 205 |

| Decile 4 | 4 | 9 | 57 | 81 | 34 | 9 | 194 |

| Decile 5 | 2 | 14 | 68 | 87 | 29 | 10 | 210 |

| Decile 6 | 1 | 12 | 64 | 85 | 27 | 10 | 199 |

| Decile 7 | 1 | 13 | 57 | 75 | 39 | 17 | 202 |

| Decile 8 | 1 | 13 | 38 | 89 | 45 | 17 | 203 |

| Decile 9 | 1 | 14 | 54 | 76 | 31 | 26 | 202 |

| Decile 10 | 1 | 11 | 57 | 75 | 40 | 31 | 215 |

| Total | 18 | 141 | 621 | 783 | 312 | 145 | 2020* |

* Number of schools entered into the Ministry’s database of schools’ financial statements, as at October 2020.

Source: The Ministry of Education’s financial information database.

3.33

About half of the schools that use the equivalent of more than 100% of their operations grant to pay staff have international students. We have identified only seven of these schools as being in financial difficulty. The 24 schools that are funding salaries equivalent to more than 150% of their operations grant are mostly state-integrated schools or special education schools that receive additional funding for staff.

Revenue from international students

3.34

For 2019, 5116 (2018: 551) schools received revenue from international students. This totalled $153 million for the year. Figures published by the Ministry show a total of 22,895 international students attended New Zealand schools during 2019, 5225 at primary or intermediate schools and 17,700 at secondary, composite, or special schools.7

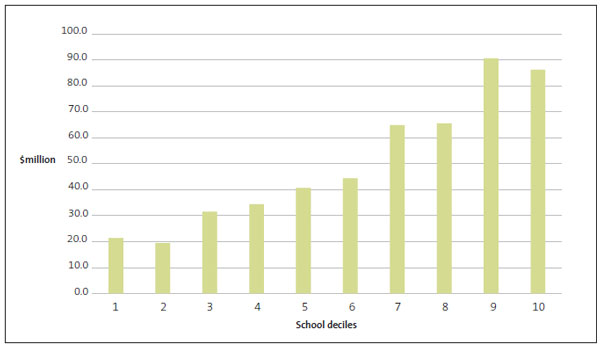

3.35

Although schools will incur additional costs for the international students, these are small in relation to the fees charged. For this reason, most schools report a large surplus on this type of revenue. In 2019, the total surplus recorded by schools was $81 million, an average of $158,033 for each school. Figure 9 shows that more higher decile schools have international students and the average surplus those schools are making on international education is higher than the lower decile schools.

Figure 9

Revenue and surplus from international students by decile

The table shows the total revenue and surplus recorded by schools in each decile. More higher decile schools have international students and the average surplus recorded by higher decile schools from international education is higher.

| Number of schools | Revenue from international students $m | Surplus from international students $m | Average surplus per school $000 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decile 1 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 41 |

| Decile 2 | 17 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 48 |

| Decile 3 | 33 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 69 |

| Decile 4 | 38 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 80 |

| Decile 5 | 47 | 9.3 | 3.7 | 78 |

| Decile 6 | 53 | 11.7 | 5.6 | 106 |

| Decile 7 | 75 | 23.1 | 11.1 | 148 |

| Decile 8 | 73 | 22.1 | 11.4 | 156 |

| Decile 9 | 79 | 44.1 | 24.2 | 306 |

| Decile 10 | 93 | 28.9 | 18.6 | 200 |

| Total | 511 | 153.2 | 80.8 | 158 |

Source: The Ministry of Education’s financial information database.

3.36

We reported last year on the risks of relying heavily on revenue from international students. Those concerns have been realised in 2020 with the closure of New Zealand’s borders. For most schools with international students, the revenue from those students was equivalent to less than 10% of the school’s total expenditure (excluding teachers’ salaries and notional rents, which are funded directly by the Ministry). However, we identified that for 2019 the revenue for 42 schools was equivalent to more than 20% of the school’s total expenditure (excluding teachers’ salaries and notional rents). The school that recorded the highest percentage had international student revenue representing 49% of its total expenditure.

3.37

The drop in revenue for 2020 for those schools with international students, which will most likely continue into 2021, could have a significant effect if the schools are unable to reduce their expenditure. This will be partly mitigated by $20 million of international student transition funding announced at the end of July as part of a recovery plan for international education, which was allocated to schools that have international students. This funding was not intended to replace missing revenue but to ensure that staff could be retained to provide pastoral care to those students still in New Zealand and help schools to transition to a future reduction in revenue from this source.

Reliance on other locally raised funds

3.38

Another likely effect of the Covid-19 pandemic is a reduction in locally raised funds. Because of school closures and uncertainties about holding large gatherings, many fundraising events have been cancelled or put on hold. The economic impact of Covid-19 and the associated uncertainties could also mean that parents and communities may be less willing or able to contribute towards school activities and events, as they may have been in the past.

3.39

Figure 10 shows that the total amount of funds raised locally by schools, $499 million (excluding international student and hostel revenue), differs between deciles.

Figure 10

Total locally raised funds collected in 2019, by decile

The table shows the total locally raised funds recorded in school financial statements for each decile. The locally raised funds collected by decile 9 and 10 schools is significantly higher than the other deciles.

Source: The Ministry of Education’s financial information database.

3.40

The impact of a possible reduction in locally raised funds will be mitigated, in part, for those decile 1 to 7 schools that opted into the Donations Scheme. This scheme gives the schools additional funding of $150 for each student if the school agrees not to ask parents for donations, except for overnight trips such as school camps. For 2020, 92% of decile 1 to 7 schools opted into the scheme.

3.41

The schools that opted into the scheme collected $36 million in donations in 2019. If we compare the donations collected in 2019 with the expected extra funding based on the school’s roll for those schools, we estimate that for 75% of schools the additional funding will compensate for the loss of donations, based on previous experience. However, we are aware that schools often record some donations and contributions from payments as “activities” revenue in their financial statements, so this analysis might not have taken into account all parent donations received by the schools.

3.42

Whether schools that have relied heavily on locally raised funds, including international student revenue, will get into financial difficulty will depend on the strength of their financial position – that is, whether they have cash reserves they can use, and whether they can put plans in place to reduce spending. Our analysis identified that many schools have healthy cash and investment balances, although these schools might be holding these funds for a particular purpose. It is important that schools budget carefully and take action to reduce their spending if they need to. There is still uncertainty and schools might not be able to rely on the funding sources they have in the past, particularly the international student market.

5: This includes funds held in school bank accounts and on term deposit for three months or less.

6: Schools with international student revenue according to the Ministry of Education’s information database as at 14 October 2020. The Export Education Levy: Full-year statistics 2019 on the Education Counts website states that 635 schools provided education to international students in 2019. The 635 includes all New Zealand schools, including privately funded schools.

7: Export Education Levy: Full-year statistics 2019. Figures include all New Zealand schools.