Part 7: Improving staff capability to support the reduction of reoffending

7.1

In this Part, we discuss:

- the Department's tools and frameworks for the ongoing training and development of staff working with offenders; and

- the Department's modernisation programme to improve technology and facilities to support staff.

Summary of our findings

7.2

The Department carried out a change programme to improve community probation work practices. The programme included preparing the Integrated Practice Framework (IPF) and the Practice Leadership Framework (PLF). The frameworks support staff to meet their mandatory standards, provide ongoing training and development, and give staff the tools they need.

7.3

The change programme created a strong platform for the Department's new strategic direction. "Unifying our effort" included rolling out the good practices prepared by community probation to the rest of the Department. Staff working in prisons and community probation are starting to talk the same language and apply consistency in practice.

7.4

The Department has a modernisation programme that includes using technology such as GPS and audio-visual links to better manage and engage with offenders. Audio-visual links in courts and prisons will reduce the costs and risks associated with transporting offenders between prisons and courts. The modernisation programme includes building and modifying facilities that help to support offenders' rehabilitation.

Staff training and development

Integrated Practice Framework

7.5

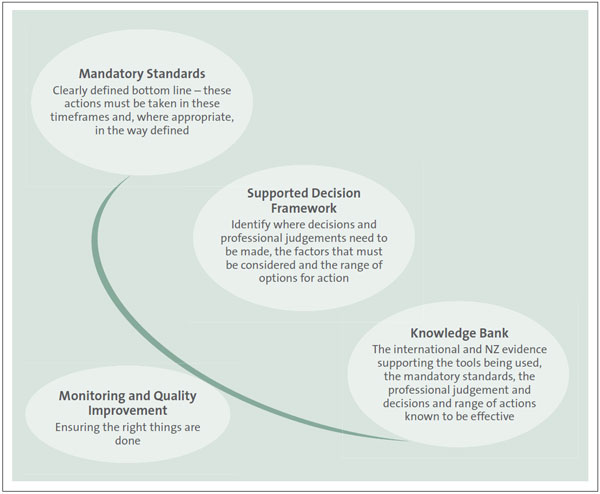

After our 2009 performance audit of the Department, community probation carried out a change programme to improve its work practices to improve public safety, which included preparing the IPF. Figure 6 describes the IPF, which includes:

- the mandatory standards specific to each sentence or order that probation officers must meet for each offender;

- a supported decision framework that identifies where probation officers can or need to use their professional judgement to make decisions about managing the offender and to help inform them about the most appropriate action to take; and

- a knowledge bank of articles and tools that probation officers can access (also known as the practice centre).

Figure 6

The Community Probation Integrated Practice Framework

Source: Department of Corrections.

7.6

The IPF was rolled out to community probation staff in a series of intensive training programmes over three years. The Department took a "reiterative approach" to the roll-out, constantly reviewing, asking for feedback on, and making improvements to the training and framework.

Practice Leadership Framework

7.7

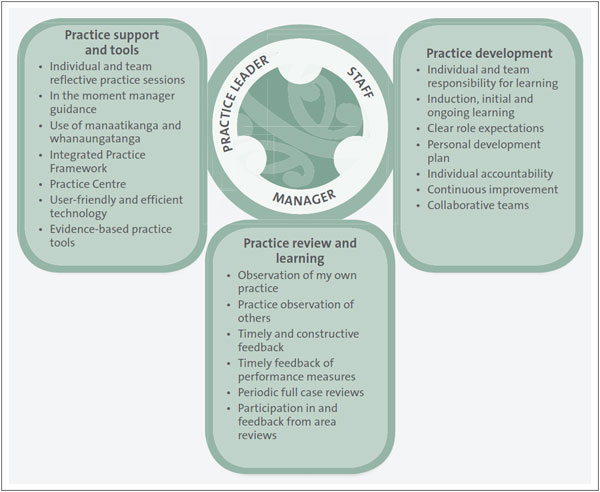

To support the roll-out of the IPF, the Department prepared the PLF to build the capability of staff. Figure 7 describes the PLF. The PLF provides training, development, and support for staff to become professional practitioners. Professional practitioners are expected to be proficient in the IPF. This includes:

- meeting all mandatory standards for all offenders;

- making decisions that are well reasoned, using the supported decision framework and taking into consideration the offender's circumstances;

- using the risk assessment tools to assess an offender's likelihood of reoffending and taking action to reduce this risk;

- engaging effectively with the offender to increase compliance and reduce the likelihood of reoffending; and

- engaging with offenders in a way that builds on and enhances cultural strengths.

Figure 7

The Community Probation Practice Leadership Framework

Source: Department of Corrections.

7.8

Practice support and leadership is provided through practice leaders and fortnightly reflective practice sessions. The sessions create an environment to support staff and provide advice on managing cases effectively. The sessions emphasise the importance of staff learning by reflecting on their work. The practice leaders provide technical guidance on how to use the practice tools, including the DRAOR.

7.9

We were told that the change programme has been successful. In November 2012, the Department received an international community corrections award for its change programme. Also, the Department met 93% of its mandatory standards in 2012/13.

7.10

In our view, the change programme has been successful because the Department embeds the IPF into the day-to-day work of probation staff and, in particular, encourages the use of practical on-the-job training led by experts. The PLF is directly relevant to probation officers' work. The reflective practice sessions that we observed show a supportive environment where staff are encouraged to openly discuss, question, and reach decisions.

Sharing good practices and combining efforts

7.11

In our view, the change programme created a strong platform for the reducing reoffending programme. At the heart of the Department's restructure and unifying its efforts was sharing good practice between staff in prisons and community probation. After the successful roll-out of the IPF and PLF, the Department is now introducing these good practices to prisons – for example, by creating the SDAC-21 based on the DRAOR.

7.12

The Department is implementing a training programme known as Right Track in prisons. Right Track is similar to the PLF and is based on active management, where staff act as change agents and use positive interaction and communication to motivate offenders to change. Prisons had used active management before, but inconsistently, and relied on individual staff using it themselves. Right Track sets up a framework for active management that provides support and professional development for staff.

7.13

The name Right Track was chosen to reflect the need to "do the right thing in the moment" and support the "right relationship". It uses an offender-centric approach to managing and interacting with offenders. All prison staff in direct contact with offenders receive Right Track training. Staff told us that Right Track was making a difference in how prison staff interact with offenders, and the programme has mostly had good support from staff.

7.14

Right Track meetings are similar to the reflective practice meetings. Meetings can include prison officers, psychologists, case managers, programme facilitators, and medical staff. "It's about how we interact as a team to better manage offenders."

7.15

Prison staff also receive training from psychologists to understand what goes on in the therapy classes. Each offender in a special treatment unit has an assigned prison officer, and training sessions ensure that prison staff and psychologists work together and share knowledge about the offender. This ensures that prison staff continue to support the values and philosophy of the therapeutic community beyond the treatment room.

7.16

Because of the PLF and Right Track, staff in prisons and community probation are starting to talk the same language and apply consistency in practice. In some instances, prison and probation staff receive joint training, such as motivation and interviewing training. The Department also provides opportunities for staff in prison and probation to shadow each other and job share. We spoke to one prison manager who thought that secondments between prison and probation staff were effective and recommended more opportunities.

7.17

The final part of the IPF is the practice centre (knowledge bank), which has a range of practice tools and strategies for probation officers to use for managing and holding offenders to account. The tools provide practical examples and activities for probation officers to work through with the offender. For example, one activity is designed to change the offender's attitude towards domestic violence. The activity involves presenting a situation that makes the offender angry and asking the offender to identify feelings that prevent them from making a change. The offender then discusses with the probation officer all the possible strategies they can use to cope. For example, "My wife nags me all the time… I'll go for a walk and think about what she is saying." We consider that the practice centre is a good resource and that preparing a similar resource for case managers would enhance their capability.

Modernisation

7.18

The Department has a modernisation programme to support staff to perform their job. Modernisation includes using technology to better manage and engage with offenders and building new facilities that help to support offenders' rehabilitation.

Global positioning system monitoring

7.19

The introduction of GPS allows for real-time monitoring of offenders in the community. Offenders wear a GPS bracelet around their ankle. This allows the Department to monitor where they go and at what time. This provides greater assurance that offenders are not reoffending.

7.20

The latest equipment is more robust than previous electronic monitoring. An alert is activated immediately if the offender tries to remove or tamper with the GPS bracelet. When an alert is set off, the GPS team immediately notifies the offender's probation officer, who calls the offender. The offender has to answer. The Department supplies the offender with a phone if they do not have one. The Department says that the GPS monitoring is working effectively and that offenders are adapting their behaviour.

7.21

The Department started using GPS monitoring for high-risk sex offenders being managed in the community. The Department sets "no-go zones" for offenders and is alerted when they enter these areas. The Department found that the monitoring worked well. They now use GPS for some offenders on home detention and release to work. This enables those offenders to access employment while being managed.

Audio visual links

7.22

The Department is increasingly using audio-visual links as an alternative to transferring offenders from prison to court. In a June 2013 press release, the Minister of Corrections stated that:

The risks associated with transporting prisoners outside the wire – to the public, Corrections and court staff – are completely removed, along with any risk of escape.

[Audio-visual links are] also more efficient, as it means Corrections and Police don't have to spend valuable time planning, carrying out, or funding escort duties from prison to court and back again. It also removes the risk of contraband being smuggled back into prisons.

7.23

In a joint initiative, the justice sector has budgeted $27.8 million to expand audio-visual links in courts and prisons to reduce the costs and risks associated with transporting offenders. Prisoner movements between prisons and courts are forecast to reduce from about 82,000 a year to about 25,000-40,000 a year.

7.24

Audio-visual links will provide some additional benefits to the Department. They will be a good tool to improve how prison and community probation staff work together to transition offenders into the community. When probation officers cannot come into prison (for example, because they are in another town), offenders could meet their probation officer through an audio-visual link before release. Prison and community probation staff could also use audio-visual links to discuss issues relevant to handover, such as joint assessments of any risks around release. Audio-visual links have the potential to save time, facilitate information-sharing, and reinforce the culture of "unifying our effort".

7.25

Audio-visual links can also be used for offenders to talk with their families, face to face, when families cannot come into the prison. Research shows that children of offenders in prison often have difficulties getting to see their parents, with more than half of the children living more than an hour's drive from the prison.

Improving facilities to support rehabilitation

7.26

As part of its modernisation, the Department is improving its facilities to support rehabilitation outcomes for offenders. We visited some of the Department's newer, open-style prisons to see the Department's vision for effective rehabilitation and reintegration. The aim of the open-style facilities is to provide and support a pro-social, pro-active environment that best enables offenders to make changes. Offenders are encouraged and supported to practise the skills that they learn in programmes. The layout of the facilities encourages interaction between staff and offenders to allow for, and to promote, active management. There is a body of evidence that this type of environment supports rehabilitation.4 The Department has an initiative to upgrade some of the ageing prisons that are inadequate for securing and humanely managing offenders.

7.27

Modernising facilities includes adapting them to provide family-friendly environments. Research has shown that children of offenders in prison are up to seven times more likely to end up in prison themselves. There is some debate about whether children should visit their parents in prison and whether this leads to children seeing the prison environment as normal. However, there is significant research that shows multiple benefits from maintaining family relationships.

7.28

Christchurch Men's Prison is working with the Pillars Charitable Trust to provide a positive experience for children when they visit their fathers in prison. They are piloting an activity space with toys and colouring books in a low-security visiting area. The activity space aims to facilitate father and child bonding and to contribute to better family outcomes. We were told that this is a big shift for the Department, which has previously feared that contraband will be smuggled in. Pillars staff told us that offenders are encouraged to interact with their children by reading stories to them and getting down on the ground and playing with them. Family visits have increased. Other prisons are also trying family-friendly ideas, such as having family days, building a children's playground, and providing fruit to children when they visit. We were told that, as well as providing healthy food, it helped create a different atmosphere.

7.29

The Department is also modernising community probation centres to encourage more successful interactions between staff, offenders, and local service providers in the community. We visited the newly built Kapiti community probation service centre. The centre is designed to maintain staff safety while also helping offenders to feel comfortable. The reception is open plan, with a front counter that is high and wide (making it hard to jump over), and there are no bars or wires between the receptionist and visitor. The centre has an open-plan design, with glass meeting rooms. The area is monitored by security cameras.

4: Pratt, J and Eriksson, A (2013), Contrasts in Punishment: An explanation of Anglophone excess and Nordic exceptionalism, Routledge, London.

page top