Part 3: Regulatory processes have been strengthened but could be improved further

3.1

In this Part, we describe how NZTA:

- has improved its processes since the regulatory failure; and

- could make further improvements.

3.2

We expected NZTA to have systems and processes in place to protect the integrity of vehicle inspections, and that it would deal with non-compliance quickly and effectively. In particular, we expected:

- a thorough appointment process to ensure that new vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations have the right skills and are of good character;

- clear and relevant requirements for inspecting vehicles;

- appropriate and effective monitoring and assessment techniques to identify non-compliance; and

- appropriate and timely action taken when non-compliance is found.

Some aspects of NZTA's regulation are done well

There is a clear and thorough application process for new vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations

3.3

The process for appointing new vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations and the requirements they need to meet are set out clearly online.

3.4

The process is thorough. Applicants are assessed on their technical competence and also need to pass a "fit and proper person" check. They are assessed at different stages of the application process by different parts of the Safer Vehicles team.

3.5

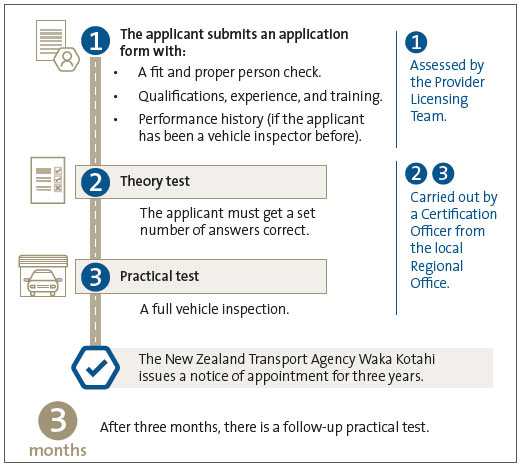

A vehicle inspector is assessed in three stages (see Figure 2). Vehicle inspectors must also hold a current driver licence for each class of vehicle they want to inspect, because they need to drive each vehicle as part of an inspection.

Figure 2

Assessment process for vehicle inspectors

3.6

There are different theory tests for certificates of fitness. There are three different categories of certificates of fitness for different classes of vehicle. Vehicle inspectors need to sit a test for each class of vehicle they want to inspect.4

3.7

Pass rates vary. NZTA staff told us that a lot more people are applying to become a vehicle inspector since the application fee was removed and people are able to keep applying until they pass. This is particularly noticeable in Auckland, where we were told that about 50% of applicants fail the theory test. NZTA told us that on one occasion it tested 12 people who had completed a vehicle inspector course (run by a third party), and only one person passed.

3.8

In the North Island, where volumes are higher, applicants sit the theory tests in groups. In the South Island, applicants are tested individually before their practical test.

3.9

The volume of testing and low pass rates suggest that this might not be an efficient use of NZTA's resources.

3.10

Additionally, more applicants mean that more practical tests are needed. This creates more work for the regional teams and takes resources away from routine monitoring. NZTA has mitigated this, to an extent, by introducing a one-month stand-down period before someone who has failed the practical test can reapply.

3.11

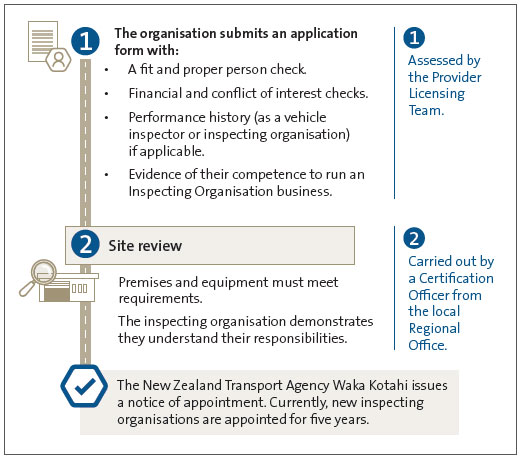

The application process for inspecting organisations has both an internal assessment and a site review (see Figure 3). If the inspecting organisation is a business with multiple sites, each site must meet the requirements. The inspecting organisation then needs to employ one or more vehicle inspectors who have passed the assessment process described in Figure 2.

Figure 3

Assessment process for inspecting organisations

Note: Documentation checks apply to the main representative of the inspecting organisation and anyone else who has significant control over the inspecting organisation, such as a director or partner, even if they do not work in the business.

3.12

In 2024, NZTA appointed on average about 60 new vehicle inspectors and about 20 new inspecting organisations each month. There is no cap on the number of vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations that can be appointed.

Vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations are regularly monitored

3.13

After a vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation has been appointed, NZTA monitors their work to ensure that they continue to comply with requirements. The main way that NZTA does this is through site reviews (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

What happens during a site review

| Before the site review |

|---|

|

The Certification Officer generates reports about the inspecting organisation and vehicle inspector they will be visiting. This report includes information about the vehicle inspectors registered to the site, compliance history, and statistics that indicate possible risk areas. Risk areas could include:

|

| At the site review |

|

The Certification Officer looks in detail through the records that inspecting organisations have to maintain. Small errors or omissions count as an item of non-compliance. There are two parts to a site review for a vehicle inspector:

This takes about an hour. If the vehicle inspector has been appointed for more than one class of vehicle, this inspection needs to be on the highest class of vehicle they can inspect. |

| The outcome of the site review |

|

The Certification Officer discusses their findings with the inspecting organisation and vehicle inspector and tells them what will happen next. This might include an educational aspect if there is something the Certification Officer considers needs improvement. A letter is sent stating the outcome and outlining any next steps (see paragraphs 3.32-3.53). |

3.14

Site reviews are carried out by Certification Officers in NZTA's regional teams. The reviews are different for vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations because they have different requirements, but are often done in a single site visit.

3.15

There is a standard operating procedure to ensure that site reviews are done consistently. Certification Officers also use a standard set of documents for each site review. These include information about the inspecting organisation and vehicle inspector under review, check sheets to record their detailed findings, guidance and reference material, and templates for letters to communicate the findings of their review.

3.16

Site reviews usually take place every three years and are usually unannounced. If non-compliance was found at a previous review, site reviews may be more frequent. Guidance for this is included in the standard operating procedure.

3.17

New vehicle inspectors also have a site review after three months, but this will be scheduled in advance.

NZTA has worked hard to clear a backlog of site reviews

3.18

Before the regulatory failure, NZTA planned to visit vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations every five years but had not been able to do so. Some had not been reviewed for more than eight years.

3.19

After the regulatory failure, NZTA reduced the standard time between site reviews to once every three years and has worked hard to complete all reviews that were overdue. This required an increase in resourcing, which was initially funded by Government loans. Funding to maintain this level of monitoring was secured after the funding review (see paragraph 2.19).

3.20

The backlog was biggest in Auckland, which experiences higher levels of vehicle inspector and inspecting organisation non-compliance than other regions. Non-compliance adds to the workload because NZTA often needs to follow up with further site reviews. Covid-19 added to the backlog because NZTA staff could not visit sites during lockdowns, which were longer in Auckland. NZTA has also found it difficult to recruit and retain the number of staff it needs to carry out site reviews in Auckland.

3.21

NZTA planned to have every vehicle inspector and inspecting organisation reviewed on a three-yearly cycle by 30 June 2024. NZTA was unable to meet this target because it was not able to secure sufficient resources. Despite this, NZTA has made good progress with reducing the backlog and, in the last three years, has reduced the total number of overdue site reviews from 2700 to 850. This is for all types of site reviews managed by the Safer Vehicles team.

3.22

To help reduce the backlog of site reviews, NZTA has also tried different ways of working, including:

- temporarily sending staff from other regions to Auckland;

- shifting a regional boundary to rebalance the number of sites regulated by each team; and

- trialling a new position to carry out the non-technical aspects of a site review (the review of an inspecting organisation's records) so that specialist staff have more time to focus on the technical aspects of the review.

3.23

We encourage NZTA to prioritise clearing the remaining backlog of site reviews. In particular, NZTA should focus its resources on site reviews it considers to be the highest risk.

NZTA also uses a mix of data analysis and following up on allegations to identify non-compliance

3.24

As well as using its regular site reviews to find non-compliance, NZTA investigates possible cases of non-compliance identified from information received (such as a complaint or allegation) or from its own data analysis. Allegations of poor or non-compliant practices can be received from the public or others working in the vehicle inspection industry. Industry organisations told us they want NZTA to deal with poor performance to protect the reputation of the industry.

3.25

Depending on the nature of an allegation, NZTA might use techniques such as a mystery shopper or covert observation to investigate the allegation and collect evidence. In a mystery shopper exercise, NZTA might take a specific type of vehicle or a vehicle with a known fault for an inspection to see whether it is inspected properly. In a covert observation, an investigator might watch vehicles being inspected from a discreet distance.

3.26

Complaints about a single vehicle are dealt with by a separate team. This is usually when a vehicle owner thinks their vehicle passed or failed an inspection incorrectly. When someone makes a complaint, they are often seeking an outcome as a consumer, such as a refund. NZTA does not have any powers to order a refund or compensation, but can provide their investigation report to the complainant for them to use as evidence should they choose to seek compensation from the Disputes Tribunal or a consumer complaints organisation.

3.27

If a complaint uncovers valid concerns about a vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation, they could receive a written warning or be subject to remedial action.

3.28

If a complaint or allegation uncovers more serious non-compliance, it will be escalated and dealt with in the same way as serious non-compliance identified during a site review (see paragraphs 3.35-3.41).

3.29

NZTA also uses data analysis to identify potential non-compliance. For example, data analysis is used to identify where vehicle inspectors have an unusually high or low pass rate for the vehicles they inspect or are issuing higher than expected numbers of warrants or certificates of fitness each day. The details of any vehicle inspectors identified in this way are passed on to the relevant regional team to investigate further.

3.30

NZTA has been using this type of analysis for the last few years. The Safer Vehicles team has introduced more powerful analytics tools and employed a dedicated data analyst. This has enabled better use of data to identify where there are risks of non-compliance.

3.31

In our view, there is scope for NZTA to use this information to develop a more risk-based approach to its monitoring, which could be a more efficient use of resources. For example, NZTA could carry out more frequent site reviews of vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations that were considered to have a higher risk of non-compliance.

NZTA responds to non-compliance in a systematic and timely way

There is a clear framework that guides NZTA's regulatory approach

3.32

NZTA has a Compliance Response Framework to support a consistent, clear, and transparent approach for all staff involved in compliance decision-making. The framework describes NZTA's approach as "firm and fair" and encourages using the right tools at the right time. For example, the framework emphasises that education and guidance might be appropriate where there is an intention to comply. However, when people take risks that could cause harm to themselves or others, NZTA will take enforcement action to reduce or eliminate the risk of harm, consistent with legal requirements. The framework sits under NZTA's regulatory strategy Tū ake, tū māia: Stand up, stand firm.

3.33

In the context of regulating vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations, NZTA uses a risk matrix with clear criteria to assess the risk of harm that could occur from an instance of non-compliance. The matrix has five risk levels, with a range of proportionate responses that can be considered for each level.

3.34

The risk matrix is included in the documents that Certification Officers use for site reviews. We observed Certification Officers referring to the matrix to make sure they were assigning the right risk level and selecting an appropriate response.

A range of enforcement options is available

3.35

NZTA has the power to take a range of actions in response to non-compliance, under the Land Transport Rule for Vehicle Standards Compliance 2002.

3.36

A low level of non-compliance, such as an inspecting organisation failing to keep its records complete and up to date, will usually be dealt with by a conversation at the time of the site review followed by a letter. Sometimes there will be a revisit after two to four weeks to see whether the aspects of non-compliance have been rectified.

3.37

Enforcement options available for more serious cases (such as failing to adequately check a vehicle's brakes) include:

- charging an infringement fee;

- suspension (removing the right to inspect vehicles) until specified conditions have been met (such as training);

- suspension for a fixed period; or

- revocation of appointment.

3.38

NZTA began charging infringement fees for non-compliance in 2024 and as of January 2025 it had issued 16. Each infringement fee is $370.

3.39

If there is an immediate risk of harm, NZTA can immediately suspend a vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation. This is a temporary suspension and provides time to investigate further before deciding on the final response.

3.40

In 2024, site reviews found that about 15% of vehicle inspectors and 26% of inspecting organisations were not complying with requirements.5 Although these rates seem high, we understand that most of the non-compliance (98%) was able to be dealt with through a follow-up review or educating those involved. More serious action was taken for the remaining 2%, such as seeking a suspension, revocation of appointment, or prosecution.

3.41

NZTA updated its prosecution policy in 2024 in line with Tū ake, tū māia: Stand up, stand firm,6 and has recently taken action to prosecute under the Crimes Act 1961.7 NZTA considers prosecution for serious offending that could compromise the integrity of the regulatory system (such as issuing warrants or certificates of fitness without inspecting the vehicle). Prosecution is also the only option NZTA has for taking legal action against anyone fraudulently issuing or selling warrants or certificates of fitness. As at January 2025, NZTA had prosecuted nine people. This is about 1% of all enforcement action taken by NZTA.

NZTA has clear roles and responsibilities for responding to non-compliance

3.42

Having clear roles and responsibilities helps NZTA ensure that enforcement decisions are made by the right people at the right time and are consistent with guidance and legislation.

3.43

Certification Officers manage low levels of non-compliance but are required to escalate cases to their regional manager when non-compliance is more serious or when lower levels of non-compliance are not resolved in a reasonable time.

3.44

These cases are considered by a panel of managers from the Safer Vehicles team. A legal advisor sits on the panel. The panel also considers cases of serious non-compliance that were identified through a complaint or allegation. The panel meets weekly and usually considers about five cases each week.

3.45

A new subgroup of the panel has been set up to consider infringements. The subgroup also meets weekly, before the main panel meetings.

3.46

The panel discusses each case in depth. It takes individual circumstances into account and considers input from a range of people. This includes the panel members, but also a separate team that puts together a report to support each case that goes to the panel.

3.47

In our view, this process could be further strengthened if the panel had a better way to record and access information from previous cases. We encourage NZTA to consider how it could record compliance decisions in a way that is easy to search for similar cases and establish more consistent precedents to follow.

3.48

The panel makes a recommendation about the appropriate response to the instance of non-compliance to the regional manager, who makes the final decision. There is a dedicated team to process decisions, such as updating systems to record a suspension.

Responses are timely

3.49

Certification Officers discuss the result of a site review with the vehicle inspector and/or inspecting organisation at the end of their visit. They follow up by sending a letter that confirms the outcome of the site review and, where applicable, the next steps, within a day of the visit. All non-compliance is recorded and tracked using a case management system.

3.50

If a follow-up visit is required, this will usually be scheduled within the next month. This gives the vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation time to rectify aspects that were not compliant.

3.51

When a decision needs to be considered by the panel, the process can take longer. The time taken depends on the circumstances and the complexity of the investigation required. The panel meets weekly, so a decision can be made quickly after the case has been put together.

3.52

However, the Senior Manager Safer Vehicles can also issue an immediate suspension. These cases will then be considered by the panel once more information is available.

3.53

In 2021/22, NZTA introduced a new performance indicator for the proportion of non-compliance actions progressed within acceptable time frames.8 The target is at least 95%. The results are published in NZTA's annual report and NZTA has met the target each year.

NZTA considers the wider implications of non-compliance

3.54

When non-compliance is found, NZTA needs to consider the validity of any warrants or certificates of fitness issued by the vehicle inspector and/or inspecting organisation involved. For example, if a vehicle inspector was found to not be inspecting vehicles thoroughly, NZTA cannot be confident that any vehicle that inspector had issued with a warrant or certificate of fitness met the required safety standards.

3.55

In these cases, NZTA can revoke the warrant or certificate of fitness of affected vehicles. When this has happened, NZTA has written to the vehicle owners to tell them the warrant or certificate of fitness is no longer valid and they will need to have their vehicle reinspected. The cost of reinspection falls on the vehicle owner, although the owner can seek a refund or compensation through standard consumer dispute channels.

Stronger relationships with industry organisations have led to improvements

3.56

NZTA told us that about 95% of vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations are either a member of the Motor Trade Association or are part of one of three national vehicle inspection businesses: VTNZ, Vehicle Inspection New Zealand, or the New Zealand Automobile Association. NZTA refers to these four organisations as its key service delivery partners. As well as being regulated parties for vehicle inspections, these organisations have other relationships with NZTA (for example, VTNZ is contracted to provide driver testing services). This means constructive relationships are important.

3.57

Improving the quality of relationships with the industry was a major focus for NZTA after the regulatory failure. Industry representatives told us that, before the regulatory failure, NZTA had not been responsive to feedback. The Safer Vehicles team now has regular engagement with the key service delivery partners, who told us their relationships with NZTA have improved significantly and that NZTA is much more open to feedback.9

3.58

Being more open to feedback is one way that NZTA can learn about how it is performing and what it needs to improve. Better relationships with the industry also support the integrity of the vehicle inspection system, through sharing information and encouraging the industry to promote higher standards of work.

3.59

There are still some areas of tension between NZTA and the key service delivery partners. This is to be expected in a relationship between a regulator and regulated parties, especially where those parties also have commercial interests. Building good relationships is important, but it is critical that NZTA maintains the right balance between its constructive engagement with the key service delivery partners and its role as their regulator.

Other aspects need further improvement

Vehicle inspection requirements could be clearer

3.60

Many of the people we spoke to told us that the manual for vehicle safety inspections, the Vehicle Inspection Requirements Manual (VIRM), is difficult for users to navigate and understand. The VIRM is available online as part of NZTA's online vehicle inspection portal.

3.61

The VIRM contains complex information, based on the legal rules for vehicle standards. It is long – if printed, it would be 1300 pages. It has a section for each part of the vehicle and sets out the reasons that would lead to a vehicle failing its inspection. The Rules it is based on are prescriptive with detailed requirements that are reflected in the VIRM. The Rules compel vehicle inspectors to focus on the specified requirement rather than the relevant safety outcome.

3.62

The VIRM is regularly updated, including in response to feedback from the key service delivery partners. Updates are sent to inspecting organisations. They are expected to inform their vehicle inspectors about all changes, and this is checked during site reviews.

3.63

NZTA has amended the VIRM to make it easier to use. It has added a search function, made it accessible on a mobile device, and added illustrations for some requirements. Updates can be accessed separately and are often explained in a newsletter that NZTA sends to vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations three times a year. NZTA has also made a series of videos about some parts of a warrant of fitness inspection. It has not had the resources to do this for every part of an inspection.

3.64

We acknowledge that the VIRM is a technical manual that needs to accurately reflect rules written in legal language and that NZTA has considered ways to help people find and understand the information. In our view, however, there is room for further improvements.

3.65

We heard that many vehicle inspectors still find the VIRM difficult to use or understand. We were told that some vehicle inspectors might not be used to navigating complex information online or struggle with the technical language, particularly when English might not be their preferred language.

3.66

Making changes to the VIRM can be difficult and time-consuming. Minor amendments such as clarifying wording are straightforward, but changing a Rule requires NZTA to work with the Ministry of Transport, who manage the policy and legislative processes.

3.67

We note that secondary legislation, like the Rules, usually deals with matters of detail or matters likely to require frequent alteration or updating. There could be an opportunity for NZTA to work with the Ministry of Transport about how it can make changes to the Rules more easily.

3.68

Requirements for inspecting organisations can also be difficult to understand. Inspecting organisations must maintain a quality management system that meets NZTA's requirements. A quality management system contains vehicle inspector records (such as training records), equipment records (such as showing that equipment has been regularly calibrated), and control sheets (to keep track of warrant and certificate of fitness check sheets and labels).

3.69

NZTA checks the completeness and accuracy of the quality management system in detail when it carries out a site review. Data from 2023 and 2024 shows that only 30-40% of inspecting organisations had all their records complete when they were inspected. A similar proportion had a small number of omissions or errors. This high rate of non-compliance suggests that inspecting organisations might be finding it hard to fully comply.

3.70

To help inspecting organisations comply, NZTA provides guidance about what needs to be included in a quality management system, as well as templates that inspecting organisations can use for each of the records required. However, the templates do not explain what sort of information they should contain or how often they should be updated. Inspecting organisations have to work this out based on the headings in each template.

3.71

One example is the template for an induction record, which is required for each new staff member. The template includes a table with a column headed "Induction required (list items that require induction)" with columns to show when each item is completed. The template does not explain what induction is or give examples of the type of induction activities NZTA expects to see. Completing this record correctly could be challenging for people who do not have experience in creating induction processes or keeping these types of records. More guidance could help with this.

The purpose of reappointment as a regulatory tool is unclear

3.72

The reappointment process is another way that NZTA can respond to non-compliance. For example, if a vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation is not meeting the expected standard of work, their appointment may not be renewed at the end of their term. Similarly, if a vehicle inspector has a persistent record of non-compliance that was not serious enough to revoke their appointment, NZTA could decide not to reappoint them when their appointment term ends.

3.73

Reappointments are usually made at the end of an appointment period, after a review of the vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation's inspection history and activity levels (that is, how many inspections they are doing).

3.74

Vehicle inspectors are appointed for a three-year period. Inspecting organisations are now appointed for five-year periods, but some were previously appointed for different terms. Inspecting organisations appointed before 2018 have an indefinite appointment (although this can be revoked for non-compliance). Some who were appointed after 2018 were given a three-year term.

3.75

NZTA plans to introduce a six-year term for appointments but does not yet have a timeframe for this change.10 It has no current plans to change the length of existing appointments, including for those on indefinite appointment terms.

3.76

If the reappointment process is to be an effective regulatory tool, it needs to be aligned with NZTA's overall regulatory approach for dealing with non-compliance. It would also need to ensure that vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations are treated consistently, fairly, and according to the risk they pose.

3.77

Reappointments could also provide an opportunity to look at matters not covered by routine site reviews, such as whether someone continues to meet the "fit and proper person" requirements.

3.78

We understand that NZTA is working with the Ministry of Transport to consider changes to its reappointment process, including any legislative change that might be required.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the New Zealand Transport Agency Waka Kotahi ensure that it has a clear and consistent process for reappointing vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations when their appointment term expires. |

NZTA's information systems and tools do not support it to work effectively or efficiently

3.79

NZTA uses a range of information systems and tools to support its regulation of vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations. However, many of these are outdated and not fit for purpose.

3.80

Many staff told us that the tools do not have the functionality they need. For example, staff told us they do not find the case management system for non-compliance helpful because it does not track cases effectively. It also does not provide prompts to help staff ensure that enforcement actions are applied within the required timeframes. Staff use spreadsheets and calendars to track their work instead.

3.81

When information is manually copied between different systems it can be inefficient and increase the risk of error.

3.82

The system used for scheduling site reviews is critical for identifying when site reviews are due, so they can be carried out within the required time frames. This system is an old Microsoft Access database and has limited functionality. Much information is entered manually. This can cause problems when people are searching for or filtering information if different words or spellings have been used.

3.83

These limitations make it difficult to extract reliable summary information, like the total number of overdue site reviews. The system does not have the functionality needed to accurately track the backlog of site reviews. This is done using spreadsheets.

3.84

NZTA told us that it has plans to replace the scheduling system.

3.85

New tools have been introduced in the last few years that allow better data analysis and dynamic reporting. A range of reports have been created that provide more insights about performance and allow staff to "drill down" for more detail. Managers can generate their own reports (for example, on the results of quality assurance reviews) to help them monitor their team's performance. New reports are frequently added to those already available.

3.86

Although the reporting tool is new, it draws on older systems and tools still in use. Each new report can take time to set up because data needs to be extracted from separate data sources and combined manually into the new tool.

3.87

NZTA is implementing a new information technology platform for its regulatory functions, including its regulation of vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations. NZTA told us that the platform is expected to provide tools that are more integrated, more efficient, and more fit for purpose. However, this is a major project being rolled out over several years and the Safer Vehicles team will not have access to all its functions for some time.11 Until it is in place, the issues and risks associated with the current tools remain.

3.88

NZTA uses separate systems for vehicle inspectors to record the results of their inspections. In October 2024, NZTA started replacing the old system for warrants of fitness (WoF Online) with a new system (VIC – Vehicle Inspection and Certification). The new system has better functionality. For example, it can be used on mobile devices and can also integrate with other systems and tools inspecting organisations might use, such as electronic inspection checklists and systems for ordering parts.

3.89

NZTA told us the transition to VIC is progressing well, with over two thirds of eligible inspecting organisations successfully using the new system by the end of January 2025. There is work in progress to support the remaining inspecting organisations to start using VIC in the next few months.

3.90

Currently only warrant of fitness and pre-delivery inspections12 can be recorded in VIC. This means that some vehicle inspectors and inspecting organisations cannot access the benefits of the improved functionality of VIC. This includes when a vehicle inspector or inspecting organisation does both warrants and certificates of fitness.

3.91

Although there is an intention to eventually move all types of inspection to VIC, NZTA told us that it does not have certainty about when funding will be available to achieve this.

4: For light passenger vehicles, applicants need to answer at least 25 out of 28 questions correctly. For general service vehicles, the pass mark is 23 out of 26. For heavy passenger service vehicles, the pass mark is 24 out of 26.

5: This excludes a low level of non-compliance where no follow-up was required.

6: See "NZ Transport Agency Waka Kotahi Prosecution Policy July 2024", available from nzta.govt.nz.

7: Prosecutions are carried out by Crown Law, supported by NZTA.

8: An "acceptable time frame" is pre-defined for some types of non-compliance action, such as complaints (20 days) or a follow-up review (one month). For other actions, the time frame is set when the action is entered into the case management system, based on the nature of the action required.

9: Other parts of NZTA also engage with the key service delivery partners and some of their comments to us are about their overall relationship with NZTA.

10: This means each inspecting organisation would have gone through two routine site reviews before their appointment is reconsidered.

11: The new platform is already in use for managing complaints.

12: Pre-delivery inspections are a type of vehicle inspection for new light vehicles.