Part 3: Matters we identified during our audits

3.1

In this Part, we set out matters that we identified during the 2022 school audits:

- schools payroll;

- cyclical maintenance;

- sensitive expenditure;

- annual reporting changes;

- budgeting;

- publishing annual reports; and

- closed schools.

Schools payroll

3.2

Salary costs are the largest operational cost for schools, and so payroll information is a significant part of the financial statements. The Ministry of Education funded about $6.4 billion (2021: $6.2 billion) of salary and employee-related costs for the 2022 school year. Education Payroll Limited (EPL) administers the school payroll on behalf of the Ministry. The education payroll pays about 97,000 teachers and support staff every fortnight.

3.3

Schools require a number of different payroll reports to complete their financial statements. The appointed auditor of the Ministry of Education carries out some testing of the payroll centrally before these reports are distributed to schools and their auditors. This is supplemented by testing locally at schools by the individual school auditors.

Centralised work on payroll

3.4

Our appointed auditor for the Ministry of Education carries out extensive work on the payroll system centrally. This includes carrying out analytics of the payroll data to identify anomalies or unusual transactions and testing all the payroll reports that are sent to schools for use in their annual financial statements. This includes reports listing payroll errors; overpayments and funding code errors (where payroll payments have been incorrectly funded by either the board or the Ministry through its teachers’ salary funding). These reports are necessary for boards to correctly reflect their payroll costs in their financial statements.

3.5

We write to the Ministry of Education every year setting out our findings from this work, with a view to improving the accuracy and reliability of the payroll data.

3.6

We continue to note improvements in the underlying processes operated by EPL, which is evidenced by the reduction in the number of exceptions identified in our data analytics work.7 Our auditors follow up any anomalies that the analytics work identifies and that cannot be resolved centrally by the Ministry of Education because the necessary information is held by the school. Some anomalies are also

sent to EPL to be resolved.

3.7

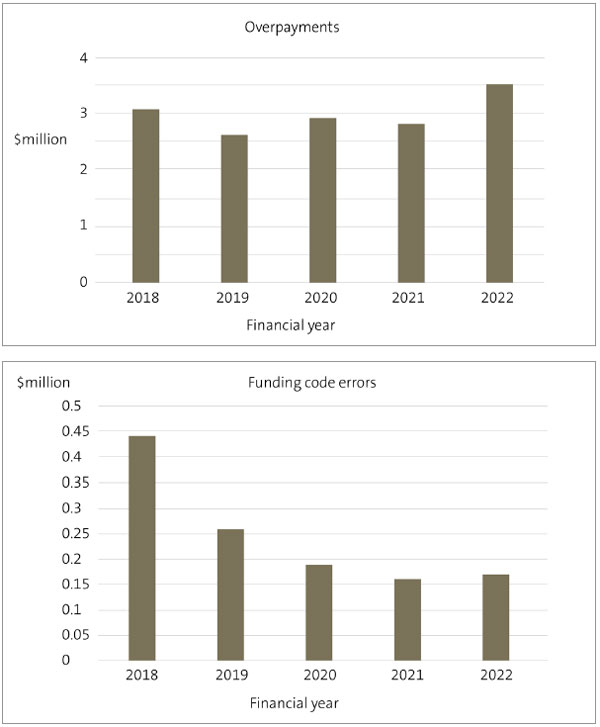

Improved internal controls built into EdPay have resulted in fewer errors identified each year, and a reduction in the dollar value of these errors. However, the removal of the Stop Pay functionality in April 2022, because the bank no longer provides this service, has contributed to an increase in overpayments compared to the previous four year (see Figure 5).8

The audit of payroll at individual schools

3.8

As well as audit work carried out at EPL and the Ministry of Education, school auditors must also carry out audit work at each school. This is because many payroll transactions are initiated by the schools, who are responsible for inputting pay information into EdPay. It is therefore important that there is a strong control environment at individual schools.

3.9

As noted above, the school payroll process has improved considerably in recent years. However, a change made to the reporting from the payroll system at a school level in 2021, as part of the implementation of EdPay, increased the amount of audit work required locally at schools for the 2021 and 2022 audits. This was because a report that many schools used to review the payroll transactions processed each pay period was no longer available.

3.10

Where possible, our auditors rely on an organisation’s controls because this reduces the amount of other testing required. The change to the payroll system in late 2021 meant that auditors could not rely on payroll controls for most schools in 2021 and 2022. Reporting was not in place at schools to provide evidence that all transactions had been appropriately reviewed for the accounting period being audited.

3.11

New regular reporting was implemented in EdPay in March 2022, enabling schools to review certain transactions processed. The guidance provided to schools explained that other reports were in development. We have been told that these reports have not been developed.

3.12

Separation of duties (more than one person being involved in a task, to prevent fraud or error) is a key control in financial systems. The expectation is that all changes to an employee’s pay or personal information should be reviewed and approved by a second independent person. Currently, the EdPay system does not allow schools to produce reports for some types of payroll changes processed in the period, which means that this second-person review and approval cannot take place. We are considering the implications this has for our approach to auditing the school payroll information for the 2023 audits.

Figure 5

Value of payroll errors, from 2018 to 2022

Source: Education Payroll Services, results and communications to the sector to support the audits of schools’ 31 December 2022 financial statements.

3.13

Our audit approach (whether we rely on controls or not) usually includes an element of analytical review, where auditors consider whether the payroll expenditure is consistent with expectations, based on a number of variables (such as salary increases and changes in number of employees). Due to the high number of changes affecting the pay of school employees in 2023 that involve many different collective agreements, setting a reasonable expectation for the payroll expenditure this year is likely to prove challenging.

3.14

Any additional payroll work required because of these factors can affect the auditors’ ability to complete all audits on time and is likely to have fee implications.

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education follow up with Education Payroll Limited to ensure that additional functions are developed and communicated to schools as indicated in the current guidance on school payroll processes and controls, so that schools are able to check and approve all transactions. |

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003

3.15

Non-compliance with the Holidays Act 2003 has been an issue for several years and affects the health sector, too. The Ministry of Education has identified that this non-compliance includes school employees, both teachers and support staff.

3.16

Because school boards are employers of school staff, they are responsible for any potential liability for this non-compliance with the Holidays Act. As for previous years, all 2022 financial statements of schools were required to disclose a contingent liability. This identifies that the school has a potential liability but the amount cannot be reliably estimated at that point in time.

3.17

In June 2023, the first Holidays Act Remediation payment was made to more than 82,000 current school employees. The affected employees received direct communication from the Ministry of Education. The total amount paid was about $38.5 million, with an average payment of $466 and a median payment of $208. These payments were made to employees by the Ministry of Education because it has decided to meet the liability on behalf of school boards, so there has been no cost to individual schools. A further payment of $2.3 million was made to about 4500 employees in November 2022.

3.18

As the employers, boards retain the obligation for the Holidays Act remediations even though the Ministry of Education has indicated that it will make the settlements. Because of this legal obligation as an employer, boards will continue to recognise a potential holiday pay liability as a contingent liability in their 2023 financial statements. The contingent liability note in the Kiwi Park model financial statements has been updated to include details of the settlements that have taken place.

Cyclical maintenance

3.19

The Ministry of Education (or a proprietor for state-integrated schools) provides schools property. Schools must keep their property in a good state of repair. Schools receive funding for this as part of their operations grant.

3.20

A cyclical maintenance provision is included in the financial statements of schools to account for their obligation to maintain the property. Schools need to plan and provide for future significant maintenance, such as painting their buildings.

3.21

Auditing the cyclical maintenance provision has always been challenging. We have reported on this aspect of the financial statements many times in the past. Many schools do not fully understand the cyclical maintenance provision and do not always have the necessary information to calculate it accurately.

3.22

The 10-year property plans of schools, which are now prepared by property consultants approved by the Ministry of Education9, should include maintenance plans that set out how schools should maintain their buildings for the next 10 years. Schools typically use the property plans to calculate their cyclical maintenance provisions.

3.23

We are still finding that many schools do not have appropriate supporting

evidence for their cyclical maintenance provisions. For the 2022 school audits, our auditors told us that about 14% (2021: 21%) of schools did not have reliable plans. We have shared this information with the Ministry of Education and will be following this up directly with the Ministry of Education’s property team.

3.24

A lack of evidence for cyclical maintenance provisions is the reason for most of our qualified audit opinions this year. A qualified opinion is issued only when the cyclical maintenance provision recorded by the school could be materially wrong. When appropriate evidence is not available, this usually requires significantly more time and effort for both the school and the auditor, and can delay the audit.

3.25

If a school has a maintenance plan prepared by a Ministry-appointed property consultant, auditors can expect the plan to have been prepared in keeping with the Ministry’s requirements and approved by the Ministry. This reduces the amount of audit work required. However, our auditors find that maintenance plans are not always prepared.

3.26

In our 2021 report on the school audit results, we repeated an earlier recommendation that the Ministry ensure that schools comply with their property planning requirements by having up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans.

3.27

If a school does not have a maintenance plan, it needs to source other information to calculate a reasonable cyclical maintenance provision. This can be time-consuming for schools and auditors. This year, auditors found that some schools without a maintenance plan struggled to get information, such as painting quotes, to support their cyclical maintenance provision because of the scarcity of suppliers. We have repeated our recommendation from previous years.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education ensure that schools comply with their property planning requirement to have up-to-date cyclical maintenance plans and review those plans to assess whether they are reasonable and consistent with schools’ asset condition assessments and planned capital works. |

Sensitive expenditure

3.28

For the 2022 school audits, our auditors brought fewer matters about sensitive expenditure to our attention than in 2021. However, we referred to sensitive expenditure in some audit reports (see paragraphs 2.37-2.41). If the amount of expenditure involved is less significant, or the matter relates to policies and procedures underlying sensitive expenditure decisions, auditors will raise the matter in the management letter rather than the audit report.

Well-being payments to schools with first-time principals

3.29

In 2022, the Ministry of Education provided a well-being support payment of $12,000 to school boards with new principals (in the role less than three years). About $6.3 million was paid to 524 eligible schools. This one-off payment as made to support the well-being of the principals and staff following the disruptions and difficulties in recent years due to Covid-19. Guidance was provided to the schools on how these funds should be used.

3.30

The final guidance issued to schools on the use of this funding required the funds to be used in a way that improves the principal’s “professional” well-being and/or supports the well-being of staff and/or the wider community. The guidance was clear that the school should be mindful of its financial obligations for school expenditure; it provided links to our guidance on sensitive expenditure and the Ministry of Education’s policies on sensitive expenditure and Principal concurrence (getting approval from the Ministry for an additional payment or benefit).10

3.31

However, some schools received a copy of draft guidance that did not specify the funding had to be used on well-being support clearly linked to their role as a principal. As well as listing examples under the headings of easing immediate workload pressures, personal development, and staff development and team culture, it included a heading that said “Treat yourself” which could be interpreted to mean the funds could be used on personal expenses. The draft guidance also did not draw attention to the school’s financial obligations when spending public money or provide links to our or the Ministry’s guidance.

3.32

As a result, some schools spent the funding in ways that could be considered to confer a private benefit, which is generally not appropriate for public funds. Examples identified this year included spending on personal trips for a principal and their family members and the purchase of personal home gym equipment. If the expenditure could be seen to provide a personal benefit, the board would have to consider whether Ministry approval was required and whether the payment could be subject to fringe benefit tax.

3.33

The differences between the draft and final guidance caused confusion. There was no evidence of clear instructions requesting that schools follow the final guidance and ignore the draft. It is the responsibility of the Ministry to provide the correct guidance to schools for properly handling the well-being payments.

3.34

Good communication is important. Although this might have been an isolated matter, we often find that schools are not aware of, or do not fully understand what is required of them (see paragraph 3.57).

| Recommendation 4 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education communicate more effectively with schools, including putting controls in place to prevent draft guidance from being sent to schools before it is finalised and approved. |

Other sensitive expenditure matters

3.35

The matters that auditors raised in management letters in 2022 were similar to previous years. They included:

- schools that did not have sensitive expenditure policies, including for gifts, or the policies were not updated regularly or deemed to be excessive (this applied to three schools);

- gifts to staff that either did not have board approval or were inconsistent with the school’s gift policy (this applied to eight schools);

- hospitality and entertainment expenses that seemed excessive (this applied to 25 schools); and

- travel-related expenditure (this applied to two schools).

3.36

Many of the matters raised with schools about hospitality and entertainment expenses were about the use of school funds for the purchase of alcohol. As we set out in our good practice guide on sensitive expenditure, there is increasingly an expectation that public organisations do not use public money to purchase alcohol. Where public organisations are still meeting the cost of alcohol, they need to have a clear justification and policies that set out the specific circumstances and limits that apply.

3.37

Most of the concerns about school policies and procedures for sensitive

expenditure payments were about poor controls over the approval of principals’ expenses or credit card expenditure. The main matters raised were:

- principals approving their own expenses or the spending was not approved by someone more senior (12 schools);

- no approval of credit card expenditure or it was not approved by someone more senior than the person incurring the expenditure (24 schools);

- inadequate or no documentation to support expenditure (six schools); and

- no approval of fuel card statements, travel vouchers, or gift vouchers (two schools).

3.38

As we have previously reported, credit cards are susceptible to error and fraud or being used for inappropriate expenditure, such as personal expenditure. Money is spent before any approval is given, which is outside the normal control procedures for spending public money. This also applies to fuel cards or store cards.

3.39

Our auditors identified four schools where funds had been used for personal use. For three of these instances, the school was reimbursed.

3.40

Schools should use a “one-up” principle when approving expenses, including credit card spending. This means that the presiding member (the chairperson) of a board would need to approve a principal’s expenses. It is also important that credit card users provide supporting receipts for the approver and an explanation for the spending.

3.41

We include guidance about using credit cards in our good practice guide Controlling sensitive expenditure.11 This provides guidance on making decisions on sensitive expenditure, guidance on policies and procedures, and examples of sensitive expenditure.

3.42

We also have other information on sensitive expenditure in the good practice section of our website.

Integrity in the public sector

3.43

Our work continues to focus on ethics and integrity in the public sector. For schools, the integrity concern is with managing conflicts of interest.

3.44

Many schools are in small communities, where the risk of conflicts of interest is high. There is a particular risk of conflicts of interest occurring when appointing new employees and contractors and purchasing goods and services. This is because a school board might have few options in a small community.

3.45

Having a conflict of interest does not mean a person has done anything wrong. However, it is important that schools properly manage conflicts and do it transparently.

3.46

In schools, the principal is also charged with governance as part of the board. All boards have a staff representative and sometimes a student representative. Integrated boards also include representatives of their proprietor.

3.47

Boards need to properly manage decisions that they make on matters that members have an interest in. A board member should be excluded from any meeting while it discusses or decides a matter that a member has an interest in. However, the member can attend the meeting to give evidence, make submissions, or answer questions.12

3.48

A good way of ensuring that there is awareness of all potential conflicts is to maintain an interests register and a formal process for declaring any interests at the start of board meetings.

3.49

We have good practice guidance on our website, including Managing conflicts of interest: A guide for the public sector and an interactive quiz that covers a range of scenarios where a conflict of interest might occur.

3.50

We have also published guidance on integrity, Putting integrity at the core of how public organisations operate. This includes an integrity framework that aims to help organisations achieve a culture of integrity in the workplace.

3.51

Other resources on our website that may be of interest to school boards include guides on:

- good governance;

- discouraging fraud;

- procurement; and

- severance payments.

Annual reporting changes

School planning and reporting

3.52

A new planning and reporting framework for schools came into effect on 1 January 2023. The Education (School Planning and Reporting) Regulations 2023 came into force on 1 August 2023. The Regulations provided more details about the framework and made the changes legally binding.

3.53

School charters have been replaced by three-year strategic plans and annual implementation plans. A school’s 2022 charter is to be treated as its first strategic plan, and the annual plan section must be updated in 2023. After that, the board must prepare the new-style strategic plan to be effective from 1 January 2024, submit it to the Secretary of Education, and publish it before 1 March 2024. The board must prepare and publish the first annual implementation plan before 31 March 2024.

3.54

Schools still need to report on their progress towards achieving the targets in their annual implementation plan. This is now called a “statement of variance” rather than an “analysis of variance”’ and forms part of the school’s annual report. There is no requirement for this to be audited.

Good employer disclosure

3.55

Section 597 of the Education and Training Act 2020 requires school boards (as employers in the education service) to have an employment policy that complies with the principle of being a good employer. The board must report on its compliance with this policy in the school’s annual report.

3.56

Before 2022, most boards were not reporting on their employment policies in their annual reports. The Education Review Office raised this matter with some schools last year. The Ministry of Education produced guidance on this requirement for the 2022 reporting year. We asked our auditors to check for this during their 2022 audits.

3.57

During the audits, many auditors found that schools were still not aware of these requirements (see Recommendation 4).

Budgeting

3.58

For the past few years, we have been reporting that many schools do not prepare budgets in sufficient detail to meet legislative requirements. Section 11(i) of the Education (School Planning and Reporting) Regulations 2023 requires each school to disclose budgeted figures for the statement of its revenue and expenses, the statement of its assets and liabilities (balance sheet), and the statement of its cash flows. Schools need to include the budget figures from their budget approved at the beginning of the school year.

3.59

Our auditors check that the numbers in the financial statements of schools are from the approved budget. However, our auditors continue to find that many schools do not prepare a budget balance sheet or a budget cash flow statement. Our auditors identified 343 schools (2021: 485) that were not preparing full budgets. This is an improvement since the 2021 audits, but there are still 14% of schools not meeting the legislative requirement.

3.60

Having a full budget, including a balance sheet and statement of cash flows, is important for good financial management. Although monitoring the revenue and expenditure of schools is important, so is managing cash flows and ensuring that schools have enough cash to meet their financial obligations when they are due. If schools do not manage this properly, they can get into financial difficulty.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education contact schools that have not previously prepared full budgets and support them to complete full budgets for the next school year. |

Publishing annual reports

3.61

Schools are required to publish their annual reports online.13 The annual report consists of a statement of variance, statement of compliance with employment policy, financial statements (including the statement of responsibility and audit report), and a statement of KiwiSport funding.14

3.62

The number of schools that publish their annual reports online has remained reasonably consistent since 2021. At the time of the 2022 audits, 88% of schools had published their 2021 annual report online (2021: 88% of schools had published their 2020 annual report online).

3.63

Although this consistency is encouraging given the delays in completing audits, there are still many schools that had not published their annual reports online. Parents and other members of a community should be able to access the school’s annual report online.

3.64

It is important that schools publish their annual report soon after their audit is completed. This ensures that they comply with legislation and are accountable to their community. If a school does not have a website, the Ministry of Education can publish the annual report on its Education Counts website.

Closed schools

3.65

The Ministry of Education has determined that closed schools need to prepare both a final set of financial statements at the date of closure and a liquidation statement, setting out how any remaining assets have been distributed. The Ministry requires both of these statements to be audited. However, it is unclear how this information is used when it is completed.

3.66

On closure, a Residual Agent is appointed to settle the liabilities of the school and disperse the assets as agreed with the Ministry of Education. We have raised concerns in the past about the delays in auditors receiving these statements for audit. We also find that there is a lack of information once the school has closed.

3.67

Despite an update of the guidance to Residual Agents a few years ago, we have not seen an improvement in the audits of closed schools. We currently have eight closed schools in arrears, the oldest one dating back to 2013. As the value of accountability reduces over time, there is a risk that when the audit is completed the information audited is no longer useful.

| Recommendation 6 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education review the requirements of Residual Agents to ensure that the financial statements of closed schools can be audited in a timely manner. |

7: Exceptions are instances that do not follow the normal pattern and might indicate errors or inappropriate payroll practices.

8: A Stop Pay is where a payment could be stopped by the bank before it was paid to the employee if an error was discovered.

9: This requirement came in on 1 July 2019. Schools update their 10-year property plan every five years so each year about 20% will update their plan.

10: “Concurrence” is agreement by the Secretary for Education to a board making an “additional payment or benefit” (a payment additional to the base salary and allowances outlined in the principal’s collective agreement or Ministry-promulgated Individual Employment Agreement (IEA)). See Circular 2020/10: Principal Concurrence – Education in New Zealand.

11: Controller and Auditor-General (2020), Controlling sensitive expenditure: Guide for public organisations, at oag.parliament.nz.

12: Section 15(1) to 15(4) of the Education (School Boards) Regulations 2020.

13: See section 136 of the Education and Training Act.

14: From 2023, boards will also be required to include and evaluation of the schools’ students’ progress and achievement and a statement explaining how they have given effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.