Part 2: What was reported?

2.1

In this Part, we set out the results of the 2022 audits3 and the results of any audits for previous years that we have completed since our report on the 2021 school audits.4

2.2

We issued a standard, unmodified, audit report for most schools. This means that, in our opinion, the financial statements for those schools fairly reflect their transactions for the year and their financial position at the end of the year.

2.3

Our non-standard audit reports include modified audit opinions or paragraphs drawing the readers’ attention to important matters. We explain these below.

Modified audit opinions

2.4

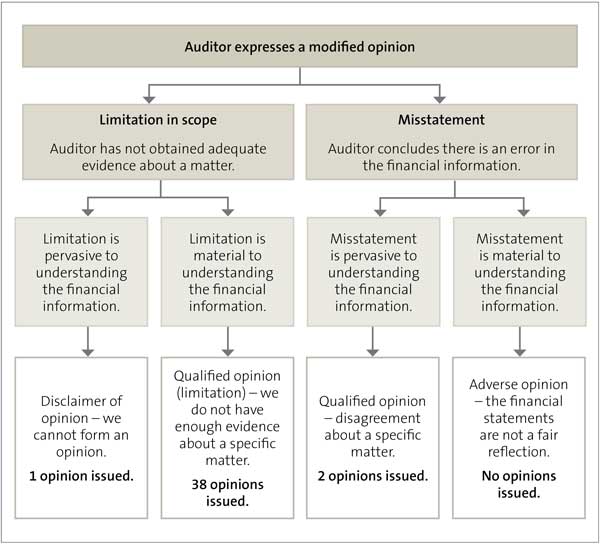

We issue modified audit opinions if we cannot get enough evidence about a matter or if we conclude that there is an unadjusted error in the financial information, and if that uncertainty or error is significant enough to change a reader’s view of the financial statements.

2.5

Figure 2 explains the different types of modified audit opinions and why we issue them. It also summarises the modified audit opinions we have issued since our report on the results of the 2021 schools audits.

2.6

Of the completed audits for 2022, 29 audit reports had a modified audit opinion. We also issued 11 modified opinions for previous-year audits that were completed since our last report.5 Although fewer than the number of modified audit opinions we issued last year, it is higher than the number of modified audit opinions we typically issued before 2020. It remains a small percentage (1%) of all audit opinions that we issue to schools.

2.7

We explain below the types of modified opinions that we issued.6

Figure 2

Types of modified opinions

Disclaimers of opinion

2.8

We issue a disclaimer of opinion when we cannot get enough audit evidence to express an opinion. This is serious because we cannot confirm that the school’s financial statements are a fair reflection of its transactions and balances. We issued a disclaimer of opinion on the financial statements of one school.

2.9

In June 2023, we completed the audit of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Takapau for 2019. We issued a disclaimer of opinion for this audit because of incomplete financial information and supporting documents from the 2018 audit, which affected the 2019 account balances.

2.10

A disclaimer of opinion was also issued for 2018. For that audit, accounting data and supporting documents up to August 2018 stored by its accounting service provider were lost. This meant that financial statements could not be readily prepared for 2018.

2.11

As a result of the lack of data for 2018, we have not been able to obtain adequate evidence to provide a basis for an audit opinion on the opening balances of accounts receivable, GST, accounts payable, finance leases, and retained earnings for 2019.

Limitation of scope

2.12

We issue a limitation of scope opinion when we cannot get enough evidence about one or more aspects of a school’s financial statements. The audit report explains what aspect of a school’s financial statements we could not get enough audit evidence for. We explain the types of limitations of scope that we reported on this year.

Cyclical maintenance

2.13

Schools are required to maintain the buildings that the Ministry of Education or their proprietor (if they are a state-integrated school) provides them. Schools receive funding to maintain their property as part of their operations grant.

2.14

Certain types of maintenance, such as painting the exterior, are needed only periodically. Schools must recognise their obligation to carry out this maintenance as a provision for cyclical maintenance in their financial statements. This provides for the cost of future maintenance required.

2.15

The boards of schools are responsible for calculating their cyclical maintenance provision based on the best information available. Auditing standards require our auditors to understand the method, assumptions, and data the school board used to estimate the provision. For several years, some boards have not had appropriate evidence that their cyclical maintenance provision is based on reasonable assumptions about future maintenance requirements.

2.16

During 2023, 30 audit opinions with a limitation of scope for cyclical maintenance were issued (23 were for 2022 audits, six for 2021 audits, and one for a 2020 audit). The 30 audit opinions issued in 2022 compares to 26 issued in 2021 and 23 issued in 2020.

2.17

Figure 3 lists the schools that did not have enough evidence for auditors to form an opinion about cyclical maintenance in 2023 (for 2022, 2021, and 2020 audits).

2.18

There could be situations where a school is uncertain about whether it needs to maintain its buildings because it has significant building works planned. Because of this, the school might not be able to estimate its future obligations for cyclical maintenance. In these cases, we expect the school to explain why it does not have a cyclical maintenance provision in its financial statements. We draw attention to these disclosures in our audit report because we consider them to be useful information for readers.

Figure 3

Schools with “limitation of scope” opinions about cyclical maintenance

| 2022 audits | Previous year audits |

|---|---|

| Aria School | Darfield School (2021) |

| Brooklyn School (Moteuka) | Hauturu School (2021) |

| Fairhall School | Hikuai School (2021) |

| Hikuai School | Matata School (2021) |

| John Paul College | Te Kura Wharekura o Ruatoki (2020) |

| Kaitoke School | Yendarra School (2021) |

| KingsGate School | William Colenso College (2021) |

| Ngatimoti School | |

| Okiwi School | |

| Otewa School | |

| Piopio Primary School | |

| Prebbleton School | |

| Rangiora Borough School | |

| Rangiora High School | |

| Sacred Heart School (Reefton) | |

| Saint Mary’s School (Blenheim) | |

| Saint Peter Chanel School (Motueka) | |

| Te Kura Toitu O Te Whaiti-Nui-A-Toi | |

| Te Ra School | |

| Te Waha o Rerekohu Combined Schools Board | |

| Timaru Christian School | |

| Timatanga Community School | |

| Upper Moutere School |

2.19

We discuss cyclical maintenance in more detail in paragraphs 3.19-3.27.

Locally raised funds

2.20

If a school receives funds from its community, it is important that it has appropriate controls to correctly record all the money it receives.

2.21

For the Taumaranui High School Community Trust, the controls for recording revenue donations were not adequate for us to rely on. There was no practical way for the auditors to confirm that all donations were included in the financial statements.

2.22

For Brooklyn School (Motueka) and Linkwater School, controls over the receipt of fundraising revenue were limited. The auditor could not confirm that the receipts from fundraising revenue were properly recorded.

Other types of limitations of scope

Overseas trip

2.23

For the 2019 and 2020 audits of Tuakau College, we issued qualified opinions because the auditors were unable to confirm the accuracy and classification of the amounts recorded in the 31 December 2019 and 31 December 2020 financial statements for an overseas trip. The school collected $371,853 in 2019 and 2020 through parent contributions and fundraising for a trip to the United Kingdom in 2020, which was cancelled due to Covid-19. The financial statements for both years included a note on the overseas trip setting out the funds collected for the trip and how the funds had been spent.

2.24

Our audit reports were qualified because the auditor was unable to reconcile the information provided in the note on the overseas trip to the amounts recorded in the financial statements relating to the trip. For example, the auditor was unable to identify where the $167,960 deposit paid to the travel agent was recorded in the 2019 financial statements.

2.25

The auditor also found that there were inconsistencies between some amounts recorded in the 2019 financial statements and how they were then recorded in the 2020 financial statements. In his audit report the auditor also brought to the readers’ attention that the note to the financial statements did not explain that the costs of the trip that could not be recovered, a total of $105,988, was paid for with fundraising money. When amounts have been collected from the school community, it is important that a school is transparent about how the money has been spent.

Fair value measurement

2.26

Blockhouse Bay School identified a weathertightness failure in one of its buildings. This resulted in inspections of the building to assess the damage and the remedial work required to resolve the weathertightness failure. The extent of damage will not be known until the remediation work has been carried out, but it has been estimated to cost between $100,000 to $250,000.

2.27

For the 2021 and 2022 audits of Blockhouse Bay School, we issued qualified opinions because the auditors were unable to determine whether there should be a reduction in the value of that building at 31 December 2021 and 31 December 2022 because of the uncertainty about the cost of the remediation work. The financial reporting standards that apply to schools require the school to consider and record any material (that is, big enough to matter) reduction in value (called impairment) of buildings in its financial statements.

Comparatives

2.28

Financial statements include information from the year before, called comparative information. The 2022 audits of Forrest Hill School, Parakai School, and Aranga School were qualified due to issues with their comparative information. For 2021, the auditors were unable to get enough assurance about the completeness of the provision for cyclical maintenance. There were no issues with the cyclical maintenance provision for 2022 and the qualification applied only to the 2021 comparative information.

Matters of importance that we draw readers’ attention to

2.29

In certain circumstances, we include comments in our audit reports to either highlight a matter referred to in the financial statements of a school or note a significant matter a school did not disclose.

2.30

These comments are designed to highlight certain matters (such as when we consider schools are experiencing financial difficulties, other information that is of public interest, or a breach of legislation) to assist readers of the financial statements. They are not modifications of our audit opinion.

2.31

We set out details of the matters we drew attention to below.

Extreme weather events

2.32

During early 2023, the North Island of New Zealand was struck by several extreme weather events. They resulted in widespread flooding, road closures, slips, and prolonged power and water outages for many communities in the Northland, Auckland, Coromandel, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, and Hawke’s Bay/Tairāwhiti regions.

2.33

Although many school sites were able to reopen soon after the extreme weather events, some school sites remained closed for a prolonged period with online learning and/or temporary alternative locations.

2.34

We drew attention to disclosures about this by nine schools. The disclosures outlined that the school faced significant damage and disruption due to the extreme weather events, and that the impact of the damage was yet to be determined at the time of signing our opinion. The disclosures also noted that the board expected repair costs to be significant.

2.35

The nine schools were:

- Eskdale School;

- Frimley School;

- Karamu High School;

- Nuhaka School;

- Omahu School;

- Saint Mary’s School (Hastings);

- Te Aratika Academy;

- Te Mata School (Havelock North); and

- Twyford School.

2.36

We also drew attention to a disclosure in the 2022 financial statements of

Mount Roskill Grammar School Early Childhood Centre Charitable Trust. The disclosure outlined that the Board of Trustees appropriately prepared the financial statements on the basis that the Trust would no longer continue. The Trust closed the Early Childhood Centre on 15 February 2023 because it had been significantly damaged by the extreme weather events in Auckland.

Sensitive expenditure

2.37

Sensitive expenditure is any spending by an organisation that could be seen as giving a private benefit to staff that is additional to the business benefit to the organisation. The principles that underpin decision-making about sensitive expenditure include that the spending has a justifiable business purpose, and that all such decisions will be subject to proper authorisation and controls. For schools, this is spending that contributes to educational outcomes for students and is made transparently and with proper authority.

2.38

We drew attention to the Board of Palmerston North Boys’ High School purchasing $31,201 of gift cards for school staff and parents for their coaching volunteer work and other sports contributions. The school did not keep adequate records to justify the spending on gift cards, the spending was not consistent with the school’s gift policy, and there was no evidence of Board approval for the purchase of the gift cards. There were also no details of the recipients for most of the gift cards given out. All school spending should be for a justifiable business purpose, be made in keeping with the board’s policy, and be adequately documented.

2.39

We drew attention to the Board of Nga Purapura o te Aroha spending $3600 on a gift for the principal for his 10 years of service to the kura. Any spending on gifts using public money should be moderate, conservative, and appropriate for the circumstances. Although the gift was approved by the Board, the kura does not have a gift policy and the amount spent was considered relatively high for a school.

2.40

We drew attention to the Board of Southern Cross Campus providing $15,000 of gift vouchers to families during the 2022 Covid-19 lockdown on the basis of hardship experienced. All spending by schools should have a justifiable business purpose consistent with the school’s objectives. Although the school had records of the families that received the vouchers, the auditor could not obtain adequate evidence to verify the criteria used for allocating the vouchers, so was unable to establish that the expenditure was directly linked to an educational purpose.

2.41

We drew attention to the Board of Shotover Primary School making a donation to the Shotover Primary School Foundation (the Foundation). As the Foundation is not a public organisation, it is not appropriate for the school to donate money to the Foundation. Because the school does not have any control over how the funds are spent, there is no guarantee that the school will receive a direct benefit from those funds. The school had requested that the donated amount be returned but no agreement had been reached at the time of the audit being signed.

Other instances

Uncertainty over services provided/lack of documentation to support payments

2.42

Since our last report, we have completed an earlier unfinished audit of the Combined Board of South Auckland Middle School and Middle School West Auckland. We drew attention to a disclosure in the 2020 financial statements of the Combined Board of South Auckland Middle School and Middle School West Auckland explaining that the Combined Board continued to pay management fees to Villa Education Trust during 2020, to the value of $200,000.

2.43

When the management fees were agreed, the Combined Board and the board of trustees of the Villa Education Trust had the same members, except for the principals of the schools.

2.44

The 2018 audit opinion of the Combined Board was qualified because the auditor could not obtain sufficient evidence for the management fees paid to the Villa Education Trust. This matter was also the subject of an inquiry by our Office.

2.45

For the 2019 and 2020 financial years, the Combined Board had entered into an agreement with Villa Education Trust to pay management fees. The agreement did not provide a detailed breakdown of the services to be provided nor did it set out how the costs of those services were ascertained. This has led to ongoing uncertainties about the services provided by Villa Education Trust to the school board.

Uncertainty over maintenance requirements

2.46

For two schools, we drew attention to disclosures about their cyclical

maintenance provisions: Gore High School and Kaikorai School. These schools could not reasonably estimate their cyclical maintenance provisions because of uncertainties about future maintenance. The uncertainties for Gore High School arose because the Ministry of Education is redeveloping part of the school. The uncertainties for Kaikorai School arose because they are part of the Ministry of Education’s Schools Redevelopment Programme, and construction is in progress. As a result, the schools cannot make a reliable estimate of the maintenance required on their buildings.

Closed schools

2.47

When a school closes, or is due to close, its financial statements are prepared on a disestablishment basis. This is because the school is no longer a “going concern”. This means that it can no longer be assumed that the school will continue to operate in the foreseeable future.

2.48

In four audit reports, we drew attention to disclosures outlining that the financial statements were prepared appropriately using the disestablishment basis. The school either stopped operating or was combined with another to form a new school.

2.49

We drew attention to disclosures in the Combined Board of Geraldine High School and Carew Peel Forest School Group’s 2021 financial statements, outlining the possible effect on the board’s financial statements as a result of the split of the Combined Board.

Going concern

2.50

We drew attention to a disclosure in Te Kura Tuarua o Kamo Trust’s financial statements outlining uncertainties about the Trust’s ability to continue as a going concern, including that the Trust’s liabilities exceed its total assets by $2,692.

Reporting on whether schools followed laws and regulations

2.51

As part of our audits, we consider whether schools have complied with particular laws and regulations. Although we mainly look at whether they complied with financial reporting requirements, we also consider whether they met specific obligations they have as public organisations.

2.52

The Education and Training Act 2020 and the Crown Entities Act 2004 are the main pieces of legislation that influence the accountability and financial management of schools.

2.53

Usually, schools disclose breaches of the Education and Training Act and the Crown Entities Act in their financial statements. However, in the interests of greater transparency we sometimes report on breaches in the audit report if we consider them to be material to the school’s financial statements or a persistent breach.

2.54

Three schools (2021: 14) borrowed more money than regulation 12 of the Crown Entities (Financial powers) Regulations 2005 allows. Schools can borrow any amount from any source as long as the annual cost to the school to repay all outstanding borrowing (including both principal and interest payments) is equal to or less than one-tenth of the schools’ operations grant. Borrowing includes loans, overdrafts, finance leases, and maintenance contracts (where schools enter into a contract to pay for the painting of the school over a fixed period).

2.55

Four schools (2021: 4) had board members who did not comply with rules in sections 9 and 10 of Schedule 23 of the Education and Training Act about conflicts of interest. For two of these instances, a board member entered into a contract in which they had a financial interest valued at more than $25,000 (including GST) without the approval of the Secretary for Education. For the other two instances, the board included a permanent member of staff who was not the designated staff representative.

2.56

Eight schools (2021: 4) invested money in a way that was not allowed under section 154 of the Education and Training Act. Some of these instances include where boards have provided loans to staff and parents without obtaining approval from the Ministers of Education and Finance. Along with providing loans to individuals, boards also cannot acquire shares in companies.

2.57

Four schools (2021: 8) did not complete an analysis of variance report for the year ended 31 December 2022. The Education and Training Act requires boards to report on any variance between the school’s performance and the relevant aims, objectives, directions, priorities, or targets set out in its school charter.

2.58

Three schools breached legislation for other reasons.

Schools in financial difficulty

2.59

Most schools are financially sound. However, each year we identify some schools that we consider could be in, or at risk of, financial difficulty.

2.60

When we issue our audit report, we are required to consider whether the school can continue as a going concern. This means that the school has enough resources to operate for at least the next 12 months from the date of the audit report.

2.61

When carrying out our going concern assessment, we look for indicators of financial difficulty. One such indicator is when a school has a “working capital deficit”. This means that, at that point in time, the school needs to pay out more funds in the next 12 months than it has immediately available. Although a school will receive further funding in that period, it might find it difficult to pay bills as they fall due, depending on the timing of that funding.

2.62

A school that goes into overdraft or has low levels of available cash is another sign of potential financial difficulty. Because we are considering the 12 months after the audit report is signed, we will also consider the performance of the school and any relevant matters in the period since the end of the financial year.

2.63

When considering the seriousness of the financial difficulty, we usually look at the size of its working capital deficit against its operations grant. Although many schools receive additional revenue, this is often through donations, fundraising, or other locally sourced revenue. Therefore, it varies from year to year. For most schools, the operations grant is their only consistent source of income.

Schools considered to be in serious financial difficulty

2.64

Not all schools with a working capital deficit at the balance date are considered to be in financial difficulty. When making this assessment, our auditors will consider other factors, including the financial performance since the end of the financial year.

2.65

When we have assessed that a school is in financial difficulty, we ask the Ministry of Education whether it will continue to support that school. If the Ministry confirms that it will continue to do so, the school can complete its financial statements as a going concern.

2.66

If we consider a school to be in serious financial difficulty, we draw attention to this in the audit report.

2.67

Figure 4 lists seven schools that received letters confirming the Ministry of Education’s support and shows whether they received such letters in the previous two years. In 2021, 19 schools received a letter confirming the Ministry’s support.

Figure 4

Schools that needed letters of support for 2022, 2021, and 2020 to confirm they were a going concern

| School | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraser High School | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Matipo Road School | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nelson College | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ngakonui Valley School | ✓ | ||

| Ross Intermediate | ✓ | ||

| Verran Primary School | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Wyndham Primary School | ✓ | ||

| Total | 7 | 4 | 1 |

Source: Schools’ financial statements and the Office of the Auditor-General’s audit reports.

2.68

As well as the schools that needed a letter of support, our auditors raised concerns about potential financial difficulties with school boards in the management letters of another 13 schools. This was usually because of continued deficits that were eroding the working capital and/or continued deficit budgeting.

Planning to avoid financial difficulty

Equity Index

2.69

From January 2023, the Ministry of Education has used the Equity Index to determine a school’s level of equity funding (which is part of a school’s operational funding), instead of the decile system.

2.70

This has resulted in significant changes in funding for some schools. Budget 2022 provided a $75 million increase in equity funding (about 6% of total school operational funding), and also provided for transitional funding so no school would be disadvantaged in the short term.

2.71

For 2023, no schools will lose funding as a result of the changes and, for 2024, no school will experience a reduction in their operational funding greater than 5%. Transition funding will be provided in the following years but will gradually reduce over time until the new funding entitlement is reached. Although there is transition funding in place, schools need to be planning for this reduction in funding and adjusting their budgets.

3: We include the audits of organisations that are related to a school.

4: Our Results of 2021 school audits report was published in March 2023.

5: One audit report included both a limitation and a disagreement.

6: These audit reports are for 2022, unless noted otherwise.