Part 2: The due diligence process

2.1

In this Part, we describe:

- what due diligence involves;

- Callaghan Innovation's due diligence process;

- how Callaghan Innovation commissioned the due diligence work;

- what Callaghan Innovation told tenderers;

- how the due diligence process was carried out; and

- our observations about the due diligence process.

2.2

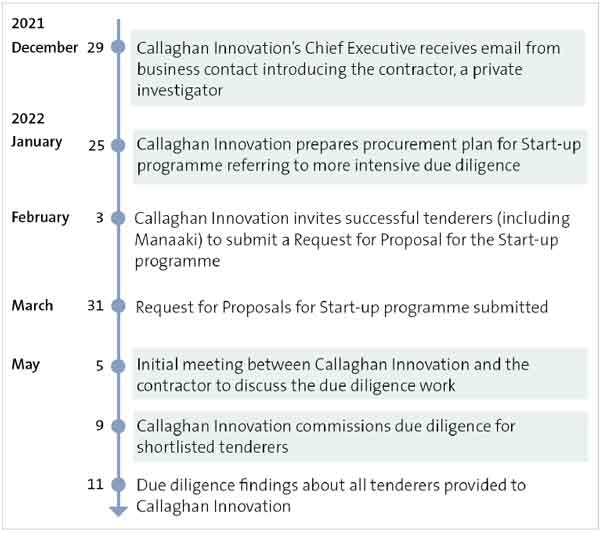

Figure 2 sets out the stages of Callaghan Innovation's due diligence process that we describe in this Part.

Figure 2

Timeline of events for the due diligence process, from December 2021 to May 2022

What due diligence involves

2.3

Ideally, identifying a serious issue or risk with a supplier should occur before a contract is awarded. Organisations do this through due diligence, which is a standard process in any procurement.

2.4

Due diligence typically involves confirming the financial resilience and viability, technical ability, and capacity of the tenderer and any subcontractors to deliver the goods or services. It often requires professional legal and financial review, assessment, and advice.

2.5

In practice, due diligence involves gathering and checking information from various sources, including from the tenderer. The more significant the contract, the more comprehensive the due diligence process should be.

2.6

The due diligence process can often include:

- assessing the tenderer's ability to deliver the goods or services for the price tendered or proposed;

- credit and reference checks;

- site visits to check the adequacy and condition of infrastructure, equipment, and resources that a tenderer will use;

- examining work or product samples; or

- considering whether there is a risk of fraud and corruption.7

2.7

MBIE has issued guidelines on this, with practical advice about planning for and conducting due diligence.8 Organisations should read the guidelines alongside the Procurement Rules and other guidance on public sector procurement, which include the expectation that the process is fair to all parties.

Callaghan Innovation's due diligence process

Background

2.8

Callaghan Innovation's Chief Executive9 told us that she was concerned about unethical behaviour towards founders in the innovation sector, including bullying, harassment, and sexism. The Chief Executive said that she had heard about this sort of behaviour in the sector and that specific concerns had been raised with Callaghan Innovation directly.

2.9

Because the Start-up programme supports founders who are sometimes vulnerable, it was particularly important for Callaghan Innovation to make sure that it put founders in safe environments. The Ministerial Direction for the Start-up programme also required Callaghan Innovation to focus on improving diversity, particularly for women, Māori, and Pasifika.

2.10

As a result, the RFP document included evaluation criteria about ethics and responsible behaviour and fostering diversity. In the scoring section of the RFP document, the categories tenderers could be scored on included "ethics and responsible behaviour", which was worth 20% of the total score, and "diversity", which was worth 10% of the total score. The RFP document also described the need to understand Māori and female entrepreneurs and their needs.

2.11

For "ethics and responsible behaviour", tenderers needed to confirm that they had policies that addressed ethical conduct, well-being, and health and safety. The RFP document also asked for examples of how tenderers had implemented these policies. For "diversity", tenderers needed to provide plans and targets to increase diversity and demonstrate an understanding of how to achieve this.

2.12

Tenderers were also provided with a copy of the proposed contract. This referred to the New Zealand Government Procurement Supplier Code of Conduct, which reinforces expectations about ethical behaviour and human rights.

The due diligence process

2.13

Because of her concerns about unethical behaviour in the sector, the Chief Executive wanted the due diligence process for selecting providers to deliver the Start-up programme to be more intensive than usual. This was described to us as a pilot.

2.14

In January 2022, Callaghan Innovation prepared a procurement plan for the Start-up programme that set out examples of due diligence that Callaghan Innovation could do. This included directly contacting any past or current contacts of tenderers that Callaghan Innovation came across in its dealings.

2.15

The RFP document replicated this part of the plan and specified that tenderers "agree not to prevent those contacts from engaging with [Callaghan Innovation] on any matter relating to the RFP". The RFP also stated that Callaghan Innovation might use a third party to help with enquiries.

2.16

We asked Callaghan Innovation what this more intensive due diligence process involved. The Chief Executive told us that Callaghan Innovation had used an AGILE approach to develop the more intensive due diligence process.10

2.17

The Chief Executive also told us that she understood that Callaghan Innovation's procurement team had legal support and had worked with an external probity advisor to manage any risks associated with the due diligence. The probity advisor told us that their involvement was limited, they gave advice based on the information Callaghan Innovation provided at the time, and they were not involved in the process in detail.11

2.18

In the Chief Executive's view, the RFP document clearly set out what Callaghan Innovation could and could not do.

How Callaghan Innovation commissioned the due diligence

2.19

In December 2021, a business contact, Mr B, emailed the Chief Executive saying that, "as promised", they were connecting the Chief Executive with a licensed private investigator (who we refer to as the contractor in this report) for any due diligence that might be needed for procurement. The Chief Executive had previously met the contractor at a conference.

2.20

In an email responding to Mr B and the contractor, the Chief Executive told the contractor about allegations she had heard about tenderers on the short list for a procurement. These included an allegation that one provider had been "taking government money with fraudulent practices underneath" and complaints of sexism and bullying about another.

2.21

The Chief Executive told us that she gave the contractor's contact details to Callaghan Innovation's procurement team and recommended that the team use the contractor for due diligence. After receiving the recommendation, Callaghan Innovation's legal team sought external legal advice about contracting a licensed private investigator to carry out due diligence.

2.22

The legal team then briefed the Chief Executive. The Chief Executive decided that Callaghan Innovation would use the contractor to carry out the due diligence.

2.23

On 5 May 2022, Callaghan Innovation sent the contractor a contract using the Government Model Contract for Services template. The contract stated that Callaghan Innovation and the contractor would "agree the scope and timeframe of any due diligence activities required, and the parties involved". Payment was based on an hourly rate. The contract was signed on 9 May 2022.

2.24

The contract required both parties to comply with applicable laws and regulations. At a meeting with the contractor on 5 May 2022, Callaghan Innovation's legal team advised the contractor to comply with legislation (such as the Privacy Act 2020 and the Search and Surveillance Act 2012), and the PSC Code of Conduct and standards for information collection when doing the due diligence.

2.25

On 9 May 2022, Callaghan Innovation gave the contractor the names of the six shortlisted tenderers for the Start-up programme, including Manaaki/We Are Indigo. On the same day, the procurement team noted in an email to the contractor that "you have stated that you have no conflicts of interest related to this activity". We discuss conflicts of interest in Part 4.

2.26

The contractor told us that he did not agree a formal scope of work with Callaghan Innovation. Instead, Callaghan Innovation relied on the contractor's expertise in carrying out due diligence. Callaghan Innovation told us that the contractor understood that his role was to provide objective information about the shortlisted tenderers for Callaghan Innovation to evaluate.

What Callaghan Innovation told tenderers about the due diligence process

2.27

Sections 3.8 and 3.9 of the RFP document set out the due diligence activities that Callaghan Innovation might carry out (see Appendix 1). These sections of the RFP also:

- stated that Callaghan Innovation could use third parties to help with enquiries;

- stated that Callaghan Innovation could perform variable levels of due diligence on tenderers; and

- explained how past experience with tenderers could be used in the due diligence.

2.28

Paragraph 6.6 of the RFP's terms and conditions sets out that Callaghan Innovation could collect additional information from a relevant third party, such as a referee or a previous or existing client (see Appendix 2). Tenderers agreed to waive any confidentiality applying to information that a third party held (apart from commercially sensitive pricing information) so that Callaghan Innovation could use that information to evaluate the tenderer's proposal.

2.29

Although Callaghan Innovation signalled in the RFP that it could use a third party to do due diligence, it did not tell tenderers who would be carrying out the due diligence as the procurement progressed.

2.30

A member of the Callaghan Innovation procurement team told us that it was concerned about the "optics" of using a licensed private investigator to do the due diligence and that this might alarm tenderers. Therefore, there was a reluctance to inform tenderers that Callaghan Innovation was using a private investigator.

How the due diligence process was carried out

2.31

The contractor started the due diligence process by verifying information about the tenderers – for example, verifying the company name and checking the identity of directors.

2.32

To identify who to interview for the due diligence, the contractor looked at publicly available information (for example, information from websites and media articles) and responses from the shortlisted tenderers to the RFP document. The contractor confirmed that the people he contacted agreed to be interviewed voluntarily.

2.33

For the due diligence on Manaaki, the contractor explained to us that he found an article about a dispute between We are Indigo (Manaaki's parent company) and another company. The contractor interviewed the director of that company. The director then suggested that the contractor talk to three other businesses that had had dealings with Manaaki.

2.34

The contractor told us that he had wanted to speak to Manaaki directly as part of the due diligence but that Callaghan Innovation said that it would talk to Manaaki. Callaghan Innovation told us that this was the more suitable approach because Callaghan Innovation was responsible for assessing and selecting the tenderers.

2.35

The contractor prepared a report on each of the shortlisted tenderers for Callaghan Innovation. The report about Manaaki set out the contractor's findings, including statements from people he interviewed. We discuss the due diligence findings for Manaaki in Part 3.

Our observations about the due diligence process

More planning was needed, and there was a lack of documentation about the due diligence process

2.36

Callaghan Innovation described the more intensive due diligence process as a pilot. Pilots typically assess the suitability, feasibility, benefits, and costs of expanding a process more widely.

2.37

When we asked the Chief Executive about the due diligence process, she told us that Callaghan Innovation used an AGILE approach to develop it. An AGILE approach typically emphasises iterative planning and communication through regular feedback.

2.38

We did not see evidence that Callaghan Innovation had taken a considered approach to how the due diligence process would work. Callaghan Innovation told us that it planned the next steps as the due diligence proceeded and that it engaged with legal and probity advisors on issues as they arose.

2.39

Callaghan Innovation directly selected the contractor to carry out the due diligence, which its procurement policy allowed because it was a low-value procurement. Callaghan Innovation told us that it took the Chief Executive's previous knowledge of the contractor from having met him at a conference into account.

2.40

We saw no evidence that the procurement team formally assessed or documented the contractor's skills or experience in due diligence for public sector procurements. We saw few documented instructions, no documented scope for the due diligence at the outset of the engagement, and limited correspondence between the contractor and Callaghan Innovation.

2.41

Most interactions between Callaghan Innovation and the contractor were verbal. No records were kept, and those involved have differing recollections about what guidance Callaghan Innovation gave the contractor. We do not consider that this is consistent with Rule 52 of the Procurement Rules, which requires organisations to keep good records of the procurement process and decisions.

2.42

It was reasonable for Callaghan Innovation to want to put in place a more intensive due diligence process, given the nature of its concerns about bullying, harassment, and unethical behaviour.

2.43

We accept that some flexibility might be needed to deal with unexpected events. However, we do not consider that Callaghan Innovation gave enough forethought to what safeguards and protections it might need when starting a process that's objective was to identify and exclude tenderers who might have previously engaged in undesirable conduct.

2.44

Given the stated concerns underlying the choice of due diligence process, it was reasonably foreseeable that issues related to poor behaviour and conduct might be raised and that, as a result, sensitive information might feature in discussions with interviewees.

2.45

Some examples of things that we consider Callaghan Innovation reasonably ought to have thought about and documented in its planning include:

- what the due diligence process would and would not involve;

- what guidance or legislation applied;

- who would do the due diligence and what skills and experience they would need (particularly in light of the potential vulnerability of the parties being interviewed);

- what protections would apply to individuals participating in the due diligence process;

- what information Callaghan Innovation would document, how the information would be used, and how the information would be kept secure;

- expectations of confidentiality – for example, what interviewees would be told about how their information might be used and what the subject of the due diligence would be told;

- what Callaghan Innovation would tell tenderers about the process, including opportunities for tenderers to respond to any adverse findings;

- how Callaghan Innovation would consider and assess the results of the due diligence process, including how the process would reflect the principles of natural justice; and

- the circumstances where confidentiality obligations might need to be overridden – for example, risk factors that might warrant a referral to another external agency.12

2.46

Apart from an email reminding the contractor of the need to abide by relevant legislation, we did not see evidence that Callaghan Innovation had addressed these matters at the planning stage. We discuss some of these matters in Part 3.

Use of a private investigator

2.47

The RFP document set out what Callaghan Innovation could do for its due diligence, including using a third party. We were told that there had been concerns about the "optics" of using a private investigator and that it was decided to not tell tenderers that a private investigator was going to do the work. This suggests that Callaghan Innovation was alert to the risks of using a private investigator.

2.48

We consider that this is inconsistent with Rule 2 of the Procurement Rules, which requires public organisations to be fair and transparent when dealing with suppliers. In our view, Callaghan Innovation should have told tenderers that it was using a private investigator to do the due diligence and who that person was.

2.49

Not disclosing who would carry out the due diligence meant that tenderers could not raise any potential conflicts of interest or risks of bias. This meant that Callaghan Innovation missed an early opportunity to identify and manage an alleged conflict of interest that Manaaki raised with it later. We discuss this in Part 4.

2.50

Callaghan Innovation told us subsequently that it made a good faith decision to enable the contractor to proceed without first informing tenderers who the contractor was. Callaghan Innovation acknowledges that, in hindsight, its judgement might not have been correct.

7: See Controller and Auditor-General (2008), Procurement guidance for public entities, at oag.parliament.nz.

8: See "Conducting due diligence checks", at procurement.govt.nz.

9: When we refer to Callaghan Innovation's Chief Executive, we are referring to the former Chief Executive who was in the role during the procurement. We use "current Chief Executive" to refer to the Chief Executive at the time we wrote this report.

10: The AGILE methodology is a way to manage a project by breaking it up into several phases. It involves constant collaboration with stakeholders and continuous improvement at every stage.

11: The probity advisor was engaged to provide probity advice for aspects of the Start-up programme. This included reviewing procurement documents supplied by Callaghan Innovation (including the procurement plan (for context), communications log, supplier briefing material, final evaluation score sheets, the evaluation recommendation report, the preliminary due diligence report, and the letter to be sent to unsuccessful tenderers), reviewing conflict of interest declarations and management plans made available by Callaghan Innovation, attending the evaluation panel moderation meeting and a meeting with Manaaki about the due diligence findings, and providing ad hoc advice on the preliminary due diligence report and the scope of the subsequent review of the due diligence process.

12: This is of particular relevance because Callaghan Innovation told us that, in late 2022, it contacted first the Police then Worksafe about the due diligence findings about Manaaki. Neither agency chose to investigate the complaint.