Part 3: The Controller function

3.1

The Controller function is an important part of the Auditor-General’s work. It supports the fundamental principle of Parliamentary control over government expenditure.

3.2

Under the country’s constitutional and legal system, the Government needs Parliament’s approval to:

- make laws;

- impose taxes on people to raise public funds;

- borrow money; and

- spend public money.7

3.3

Parliament’s approval to incur expenditure is mainly provided through appropriations,8 which are authorised in advance through the annual Budget process and annual Acts of Parliament. When the Government wants to incur expenditure not yet authorised in an Appropriation Act, it can draw on the Parliamentary authority provided in an Imprest Supply Act. Expenditure can be authorised in advance through permanent legislation. Some expenditure can also be approved retrospectively.

3.4

The incidence of unappropriated expenditure reached a historical low in 2020/21. This continued in 2021/22, with 12 instances reported in the Government’s financial statements. The amount of unappropriated expenditure as a percentage of the Government’s budget also remained constant, at 0.09% of the budgeted spend.

3.5

In this Part, we discuss:

- why the Controller work is important;

- how much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2021/22;

- why the expenditure was unappropriated;

- how 2021/22 compared with previous years; and

- a summary of work we carried out in 2021/22 to discharge the Controller function.

Why the Controller work is important

3.6

Appropriations ensure that Parliament, on behalf of the public, has adequate control over how the Government plans to spend public money. They also ensure that the Government can be subsequently held to account for how it has used that money.

3.7

Most of the Crown’s funding is obtained through taxes. Parliament and the public are entitled to assurance that the Government is spending public money as authorised by Parliament.9

3.8

As the Controller, the Auditor-General helps maintain the transparency and legitimacy of the public finance system. The Auditor-General provides an important check on the system on behalf of Parliament and the public by providing independent assurance that the spending is within authority. The Auditor-General also provides assurance that any government spending without authority has been identified and dealt with appropriately. As an Officer of Parliament, the Auditor-General is independent of the Government.

3.9

In the Appendix, we explain how public expenditure is authorised, who is responsible for managing it, and the Controller’s role in checking it.

How much public expenditure incurred in 2021/22 was unappropriated?

3.10

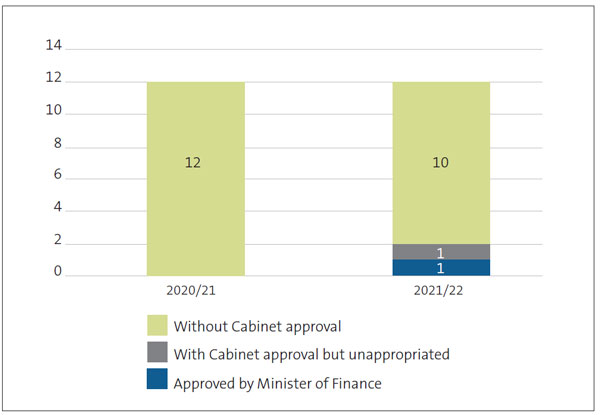

The Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2022 report 12 instances of unappropriated expenditure (2020/21: 12). Expenditure incurred above or beyond appropriation10 for 2021/22 was $162.5 million (2020/21: $133.7 million). Figure 1 shows a breakdown of unappropriated expenditure categories.11

Figure 1

Unappropriated expenditure incurred for the year ended 30 June 2022

| Category | Unappropriated expenditure by category | 2021/22 Number | 2021/22 $million* | 2021/22 Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act 1989. | 1 | 0 | Māori Development |

| B | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but in excess of appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | 1 | 3 | Conservation |

| C | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but without appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | - | - | |

| D | In excess of appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 5 | 19 | Conservation; Ombudsmen; Social Development; Finance |

| E | Outside scope of an appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 2 | 24 | Foreign Affairs, Social Development |

| F | Without appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 3 | 115 | Revenue; Business, Science and Innovation |

| Total | 12 | 162 |

* Amounts are rounded to the nearest million.

3.11

The unappropriated expenditure categories shown in Figure 1 fall into three broader categories:

- Approved by the Minister of Finance (Category A): Small overruns of expenditure in the last three months of the financial year (that is, within $10,000 or 2% of the appropriation) may be approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act. Although unappropriated, expenditure approved under section 26B is lawful. There was one instance of unappropriated expenditure authorised under this section for 2021/22 (2020/21: No instances).

- With Cabinet approval (Categories B and C): When it is anticipated that expenditure will be incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits, departments should seek prior Cabinet approval to use imprest supply for the spending not covered by appropriations.

- However, the use of imprest supply is only an interim authority (it expires on 30 June each year), so all spending using this authority must also be appropriated through an Act of Parliament by 30 June (see the Appendix for how appropriations work).

- Sometimes Cabinet’s approval to use imprest supply is obtained but the extra spending is not included in an Appropriation Act12 before the end of the financial year, so the spending remains unappropriated.

- There was one instance of unappropriated expenditure in this section in 2021/22 (2020/21: No instances).

- Without prior Cabinet approval (Categories D, E, and F).

- For 2021/22, the Government’s financial statements report 10 instances of expenditure incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits without any authority at the time it was incurred, that is, without Parliamentary appropriation and without Cabinet’s prior approval to use imprest supply (2020/21: 12 instances).

3.12

Figure 2 shows a continuation in 2021/22 of the low number of instances of unappropriated expenditure (see Figure 5 for a seven-year time series), with two fewer instances of expenditure without prior Cabinet approval than for 2020/21.

Figure 2

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2022

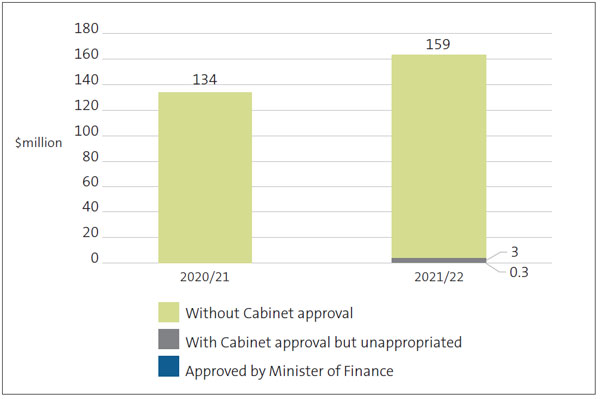

3.13

Figure 3 compares the dollar amounts of unappropriated expenditure for 2020/21 and 2021/22. The amount of unappropriated expenditure increased from $134 million for 2020/21 to just over $162 million for 2021/22.13

Figure 3

Amount of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2022

3.14

Expenditure outside the bounds of the appropriations tends to be relatively low. Unappropriated expenditure of $162 million for 2021/22 was 0.09% of the Government’s final budgeted expenditure for that year, the same percentage as in 2020/21.

Why was the expenditure unappropriated?

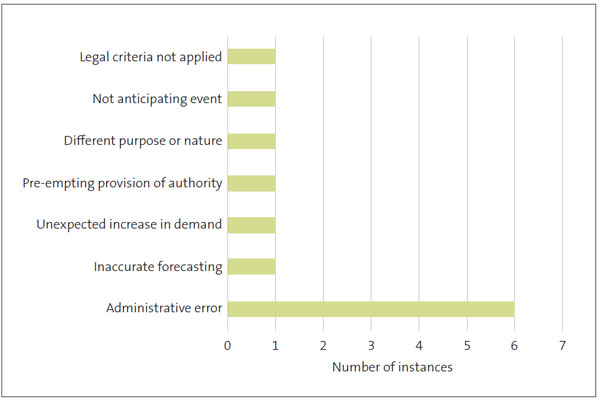

3.15

We assigned the instances of unappropriated expenditure into seven categories that describe why the unappropriated expenditure came about (Figure 4). Administrative errors feature heavily. Six of the 12 instances resulted from administrative oversights and accounted for 75% of the $162 million of unappropriated expenditure.

Figure 4

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure in 2021/22, by number of instances

Legal criteria not applied

3.16

The Social Security Act 2018 provides for accommodation assistance payments to eligible recipients, in accordance with criteria set out in the Act or in delegated legislation made under the Act. Most of the accommodation assistance is in the form of the Accommodation Supplement, which was established on 1 July 1993.

3.17

Since the payment was introduced in 1993, the Ministry of Social Development (the Ministry) has been applying different payment criteria from that laid out in legislation. This means that some of the payments made over the last 29 years have been unlawful under the Social Security Act and are, consequently, unappropriated. Specifically, the Ministry has been paying the grant at the single rate to “community-based partners” when it should have been paying them at the (usually lower) couples’ rate.14

3.18

In May 2019, the Ministry became aware that its approach to paying this grant to community-based partners was unlawful. Until 2019, it was operating in the belief that it was complying with the legislation. After learning that its approach was not supported by the legislation, the Ministry has continued to make the unlawful payments. It told us that it considers its approach to be consistent with the original intent of the policy for the Accommodation Supplement.

3.19

In March 2022, the Ministry became aware that its practice had led to a breach not only of the Social Security Act but also of the Public Finance Act, because payments to community-based partners were outside the scope of the Accommodation Assistance appropriation. After learning that its payments were unappropriated, the Ministry proposed changes to the legislation that would bring the law into line with its current practice. However, the Ministry’s proposal involved continuing to make the unlawful and unappropriated payments for at least a further 14 months.

3.20

Our auditors were informed in May 2022, at the same time that the Ministry was considering its options to resolve the issue. After receiving key documents from the Ministry in September 2022, our Controller team advised the Ministry that the Controller considered that the situation was unacceptable and should be resolved urgently. The Controller wrote to the Ministry in October 2022 expressing his concerns and outlining his expectation for urgent action.

3.21

For the historical expenditure, we consider it impracticable for the Ministry to identify every unappropriated payment back to 1993. The Ministry’s financial statements for 2021/22, and the Government’s financial statements for 2021/22, disclose the amount of unappropriated expenditure for the last five years. The financial statements also disclose that expenditure has been incurred unlawfully since 1993. In our view, these disclosures provide enough transparency about the nature and extent of the unauthorised expenditure.

3.22

Unappropriated expenditure on the Accommodation Supplement was $5.9 million for the last five years, including $1.5 million for 2021/22. Unappropriated payments continued until 25 November 2022, when amendments to the Social Security Act and Regulations made the current practice lawful.

Not anticipating an event

3.23

From time to time, the majority Crown-owned energy companies will issue new shares as part of their dividend reinvestment plans. The Crown’s participation in these plans is necessary to ensure that it maintains its majority shareholding. Parliament authorises the Crown’s reinvestment in the energy companies through a specific appropriation in Vote Finance.

3.24

Meridian Energy Limited announced on 30 March 2021 that it would apply a dividend reinvestment plan to its next dividend payment, in October 2021. On 15 October 2021, the company paid a dividend, resulting in the Crown receiving new shares valued at $33 million. However, the appropriation that authorises such reinvestments had not been increased to cover this event. The authority available at the time was only $21.3 million, which meant that $11.7 million of the investment was unappropriated expenditure.

Different purpose or nature

3.25

The New Zealand Antarctic Institute, which runs Scott Base, received spending authority under Vote Foreign Affairs to maintain the Scott Base buildings and services infrastructure.

3.26

Funding received in Budget 2021 was intended for the redevelopment of Scott Base. Redevelopment work is of a different nature from maintenance work, but redevelopment costs were not within the appropriation scope.15 The scope needed to be amended to provide authority for this expenditure, but it was not. Consequently, $23 million of redevelopment costs were unappropriated.

Pre-empting provision of authority

3.27

Unappropriated expenditure can occur when departments seek expenditure transfers from one year to the next. We have previously urged government departments to better manage the transfer of spending authority between years.

3.28

If activities authorised for a particular financial year are delayed or otherwise deferred, it is common for government departments to request an in-principle expense transfer (and associated funding) to the following financial year. If the transfer is granted in principle, the department must seek confirmation of the transfer during that (following) financial year. If confirmed, the department will need to seek approval under imprest supply to incur the expenditure, unless the spending is already covered by the Budget Act for that year.

3.29

Between-year expense transfers are usually confirmed – and authorised under an Imprest Supply Act – in October of each year, after the departments’ financial statements have been audited and published. However, if the expenditure needs to take place before then, the departments need to ensure that the correct financial authority has been provided in time.

3.30

One such instance arose in 2021/22 under the Vote Conservation appropriation for the vesting of reserves. The transfer of a Reserve to a third party had been delayed from 2020/21 to 2021/22, and the Department of Conservation had requested an expense transfer from 2020/21 to 2021/22 to cover it. However, the land transfer was finalised in September 2021, before the expense transfer and the authority to use imprest supply had been approved in October 2021. This resulted in $3.1 million of unappropriated expenditure.

Unexpected increase in demand

3.31

Social housing tenants’ Income Related Rent costs are based on their income. If their income decreases, a reassessment of what they are entitled to is likely to result in a reimbursement of overpaid rent. Vote Social Development includes an appropriation that expressly authorises these reimbursements.

3.32

The Covid-19 pandemic led to an increasing number of tenants experiencing reduced hours of work (and therefore reduced income) or loss of employment. By April 2022, reimbursements had exceeded the authorised amount. The Ministry of Social Development obtained extra spending authority under imprest supply in mid-April to ensure that future reimbursements were authorised. However, $171,000 had been paid in excess of appropriation before the imprest supply authority was received.

Inaccurate forecasting

3.33

Vote Māori Development includes an appropriation, Rōpū Whakahaere, Rōpū Hapori Māori | Community and Māori Governance Organisations, which authorises expenditure to support Māori community and governance organisations.

3.34

After Budget 2021, Parliament authorised $19.875 million for this activity but this was reduced by $450,000 in the updated Budget as funds were diverted to the Covid-19 response. Consequently, Parliament authorised the lower amount of $19.425 million through the Supplementary Estimates Act.

3.35

However, a review by Te Puni Kōkiri of its forecast expenditure on commitments identified that it would need spending authority closer to the original budget for that appropriation. The department sought and received the Minister of Finance’s approval, under section 26B of the Public Finance Act, to incur $342,000 in excess of the $19.425 million authorised.

Administrative error

3.36

Half of the unappropriated expenditure instances resulted from administrative errors. Six instances of unappropriated expenditure have resulted from four administrative oversights, in Vote Conservation; Vote Revenue; Vote Business, Science and Innovation; and Vote Ombudsman.

3.37

The Community Conservation Funds appropriation authorises the payment of grants for community groups and private landowners to carry out work on public and private land; to assist with pest and weed control, fencing, and other biodiversity management actions; and to support community biodiversity restoration initiatives. In updating its Budget, the Government planned to reduce the level of spending authority for this appropriation through the Supplementary Estimates Act. The reduction was inadvertently made twice, and this resulted in expenditure exceeding the final appropriated amount by $6.8 million.

3.38

The Department of Conservation sought and obtained Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. Up to that point, $3.5 million had been incurred without Cabinet authority, with $3.3 million incurred with Cabinet authority but nonetheless unappropriated.16

3.39

By 28 June 2021, Cabinet had agreed to reactivate the Covid-19 Resurgence Support Payment scheme following a shift to higher alert levels. The purpose of the scheme (administered by Inland Revenue) was to help alleviate the economic effects of the alert level requirements on businesses.

3.40

Budget 2021 did not provide for this expenditure in Vote Revenue, so Inland Revenue needed to obtain approval to use the interim authority available under the Imprest Supply Act. Because the wording of the initial recommendation to Cabinet to reactivate the scheme in July 2021 omitted the request for imprest supply, there was no financial authority in place when the payments began. The oversight was identified in early July 2021 and imprest supply authority was provided on 15 July. By then, $4.77 million had been paid without authority. Payments after that date were made with the correct authority.

3.41

Two multi-year appropriations under Vote Business, Science and Innovation were set to expire on 30 June 2021. They each provided authority for three years of infrastructure spending (from 2018 to 2021) for Regional Digital Connectivity Improvements and Broadband Investment. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment obtained Ministerial approval to extend the period of the two appropriations by a further year.

3.42

The Ministerial approval then needed to be reflected in a special clause in the Supplementary Estimates Act17 to provide the legal authority for the extension. However, the Treasury omitted to include the clause in the Supplementary Estimates Bill, which meant the legal expiry date for the appropriations remained as 30 June 2021.

3.43

The Treasury error was identified in mid-2022, by which time the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment had incurred expenditure (since 1 July 2021) within the scopes of each of the expired appropriations. Expenditure of $33 million on regional digital connectivity improvements was unappropriated, as was $77.5 million on broadband investment.

3.44

The Office of the Ombudsman obtained approval for an additional capital injection in 2021/22, which was authorised in June 2022 through the Supplementary Estimates Act.18 The Office drew down the capital injection ($568,000) in May 2022 before the Act came into force. It could have legally accessed the capital funding in May had interim authority under the Imprest Supply Act been in place at the time. This oversight resulted in the capital injection being unauthorised. The Ombudsman returned the funding to the Crown after the error had been identified.

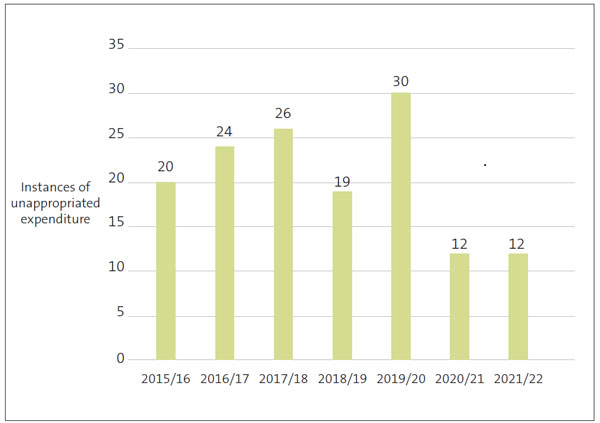

How does 2021/22 compare with previous years?

3.45

The significant decrease in the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure in 2020/21 held constant in 2021/22. The Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2022 report 12 instances of unappropriated expenditure which, along with the 2020/21 figure, represents a historical low.

3.46

For the last two years, the annual number of instances is down to around half of those in the five years before (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure, from 2015/16 to 2021/22

3.47

Figure 6 shows the dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred during the last seven years. The dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure tends not to correlate with the number of instances. Apart from an outlier year (2019/20), which is mostly attributable to one instance ($676.8 million), the value of unappropriated expenditure follows the usual fluctuations over time.

Figure 6

Amount of unappropriated expenditure, from 2015/16 to 2021/22

Work carried out to discharge the Controller function

3.48

During the year, we carried out our core Controller work through our regular monitoring (with the Treasury) of expenditure against appropriations.19 As part of this work, we check that government expenditure incurred under the authority of the Imprest Supply Acts (see the Appendix) has not exceeded the spending limits authorised under those Acts. We also check that Cabinet approvals to use imprest supply have been properly authorised.

3.49

Other core Controller activity involves our audits of appropriations and audits of the Government’s financial statements and of individual government departments.20

3.50

We published website reports on observations and findings from our monitoring of government expenditure, including a half-year report on expenditure against appropriations. We also published a website report on how changes are made and approved to the Government’s Budget between the annual Budgets, how they are scrutinised and authorised through the Supplementary Estimates, and the Controller and Auditor-General’s role in monitoring these approvals.

3.51

The authority to incur expenses or capital expenditure provided by an appropriation is limited to the scope of the appropriation and may not be used for any other purpose.21 The scope statement of an appropriation establishes the legal boundary of what an appropriation can be used for and, by omission, what it cannot. It is intended to provide an effective constraint against unauthorised activity while not inappropriately constraining activity intended to be authorised.

3.52

Several government departments provide services, including development assistance, to other countries. The Controller needs to be able to provide assurance to Parliament and the public that any public money applied for the benefit of foreign jurisdictions has been authorised by Parliament.

3.53

During 2021 and 2022, we discussed with the Treasury whether overseas assistance spending was covered by the appropriation scopes in all instances. We expect government departments to ensure that any overseas expenditure is covered by their appropriations, and we will be asking our auditors to give attention to this as part of their audit work.

3.54

We again participated in the Treasury’s Finance Development Programme of seminars to government department finance professionals. We highlighted the importance of Parliamentary control of Crown spending, how the Controller function supports New Zealand’s constitutional arrangements, why it is important to avoid incurring public expenditure without the proper authority, and some of the common problems that can lead to unappropriated expenditure.

7: Section 22 of the Constitution Act 1986.

8: Appropriations are authorities from Parliament that specify what the Crown may incur expenditure on (specific areas of expenditure). Most appropriations specify limits in terms of the type of expenditure (the nature of the spending), scope (what the money can be used for), dollar amount (the maximum that can be spent), and period (the time frame for which the authority is given).

9: That is, it is within the type, scope, dollar amount, and period limits authorised by Parliament.

10: That is, in excess of the maximum amount or outside the scope authorised by Parliament.

11: The Treasury (2022), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2022, Wellington, pages 158-162.

12: Normally through the annual Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Act.

13: The Treasury (2022), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2022, Wellington, page 158.

14: Community-based partners are recipients who reside in the community and whose partners are in residential care.

15: The appropriation scope statement sets out the legal boundary of what an appropriation can be used for and, by omission, what it cannot.

16: Because the unappropriated expenditure is split between two categories in the Financial Statements of the Government, it has been counted as two instances.

17: Appropriation (2020/21 Supplementary Estimates) Act 2021.

18: Appropriation (2021/22 Supplementary Estimates) Act 2022.

19: Under section 65Y of the Public Finance Act 1989.

20: Under section 15 of the Public Audit Act 2001.

21: Section 9 of the Public Finance Act 1989.