Part 4: Opportunities to improve performance reporting

4.1

Our work suggests that the "vicious cycle" Gill described in 2011 still exists today (see paragraphs 2.30-2.31). Many well-considered initiatives have been tried, but they often still focus on what is important to public organisations and not on what is important to Parliament and the public.

4.2

In this Part, we consider changes that might help to improve the usefulness and value of performance reporting for those who need it. We also look at some performance reporting innovations from New Zealand and other countries.

Five areas of focus that could help improve performance reporting

4.3

Our research suggests that performance reporting is not contributing to effective public management, finance, or accountability as well as it could be. There is no one, single problem with performance reporting. The issues involved are complex. Furthermore, because there is not just a single problem with performance reporting, there can be no single answer.

4.4

Performance information must be meaningful to Parliament and the public if we want them to read, understand, and use it. There are already signs that public organisations understand the need for new approaches. However, in our view, systemic change is needed for performance reporting to fully realise its potential.

4.5

In our view, there are five areas where improvements could be considered. These are:

- focusing performance reporting more on the issues that matter to New Zealanders;

- more tailored reporting of performance;

- integrating and aligning information better;

- providing more support to assist with monitoring and scrutiny; and

- building demand, leadership, and capability.

Shift the perspective towards New Zealanders

4.6

In the last few decades, the legislation, policies, and guidance that underpin the public finance, management, and accountability systems have largely focused on improving the effectiveness and efficiency of public organisations.

4.7

This is likely to have improved the service delivery of public organisations. It has also helped maintain the high level of trust that most people have in public services based on their personal experiences.54

4.8

However, New Zealand is changing. As we observed in our recent discussion papers Public accountability: A matter of trust and confidence and Building a stronger public accountability system for New Zealanders, public organisations today are facing a new set of complex and longer-term challenges.

4.9

Managing these will require public organisations to act as stewards of New Zealanders' intergenerational well-being. To support this focus, new approaches to public accountability are needed.

4.10

Boston, Bagnall, and Barry recognise this shift in focus and note that "if Parliament is to scrutinise the performance of the executive, assessing departmental stewardship in its various forms must be a core feature of such oversight".55

4.11

The response to Covid-19 indicates that government action alone is not always enough to achieve successful outcomes. People's buy-in and trust is also needed. The long-term success of the public sector's response to Covid-19 is not just about delivering services and outcomes effectively and efficiently, but also about the public sector maintaining a trusted partnership with communities.

4.12

This might mean it is time to reconsider the way public sector performance is thought about, analysed, and reported on to better reflect what is important to the public. This might mean public organisations:

- working more closely with Parliament, select committees, and other public stakeholders to understand what information is important to them;

- developing new ways of reporting on the management of complex long-term issues that matter to the public;

- reporting on a wider set of behavioural-related attributes, such as respect, integrity, sustainability, collaboration, participation, and inclusion;

- accounting for a broader range of the public organisation's assets and liabilities that support the stewardship of New Zealanders' intergenerational well-being;

- explaining more clearly how the public organisation uses public money to generate value for the public;

- integrating and sharing results between public organisations to describe performance in a way that includes outcomes, sectors, and the whole of government; and

- aligning the public organisation's funding requirements to the services and outcomes that are important to people's well-being rather than only to the inputs and outputs of its activities.

4.13

Integrated reporting is one method that attempts to account for a broader range of organisational assets and liabilities. This focuses on the relationships between a broad base of organisational capitals, including financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural.

4.14

Integrated reporting is designed to clearly show how an organisation's strategy, governance, performance, and prospects, in the context of its external environment, create value in the short, medium, and long term.56

4.15

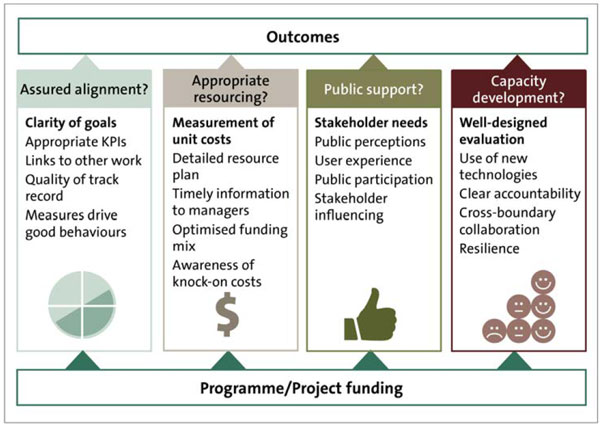

There are also examples in other countries that might be useful to consider. For example, in 2019, Her Majesty's Treasury asked departments and other public bodies in the United Kingdom to use their Public Value Framework57 to guide their planning, everyday decision-making, and reporting processes.

4.16

Instead of focusing on quantifying the inputs and outputs of departments and observing the relationship between them, the framework focuses on the process of improving the value of public money.

4.17

Success is defined by four broad organisational activities or pillars. These are how the department:

- pursues and monitors its overall goals;

- manages its financial inputs;

- supports long-term sustainability by developing system capability; and

- engages citizens and users to understand their needs and gain their support.

4.18

Guidance on the framework recognises that most organisations will find engaging with the public and demonstrating that engagement new and challenging. However, the guidance also says that:

By collating insights from citizens and users, it becomes possible for government to focus its efforts on activities that will result in genuine improvements to people's lives and thus, maximise public value.58

4.19

Figure 3 provides one example of how Historic England59 draws on the Public Value Framework to assess and report on the public value of the outcomes it achieves with public money.

Figure 3

Historic England's public value framework

Source: Adapted from the Historic England, Public value framework, at historicengland.org.uk.

4.20

In New Zealand, initiatives such as the Policy Project support many public organisations to engage with communities when designing and developing policies.60 Using a similar process to develop more relevant and accessible reporting to those communities could be useful.

More tailored performance reporting

4.21

Although legislation gives public organisations flexibility in what performance information they present,61 that information is not always analysed and presented in a relevant and accessible way.

4.22

A new balance might need to be struck between what public organisations are formally required to report to Parliament and what the public and communities need to know to better understand public sector performance.

4.23

Making performance reporting more useful and valuable will require public organisations to move away from the largely one-size-fits-all exercise that exists today. For example, it could mean:

- reporting performance through more accessible channels (not just in annual reports);

- a greater focus on what it means to be stewards of New Zealanders' intergenerational well-being; and

- different ways of analysing and presenting performance.

4.24

Different users of performance information have different needs. For example, in the context of the transport sector:

- communities might focus on the quality of roads in their region, how quickly road damage is fixed, and whether roads are open and safe for pedestrians, drivers, and cyclists;

- industry bodies might be interested in how well the public sector works with the industry, and the progress and value for money of government investment in motorways; and

- Parliament might be interested in how well public organisations are funded and whether they work well, individually and collectively, to deliver the government's transport priorities.

4.25

In terms of their relevance and usefulness to particular audiences, how measures are determined can be as important as what they measure. Co-developing indicators and reporting with the public could help ensure that there is a well-informed and generally accepted way of demonstrating performance. Recent research also suggests that collaborating with stakeholders to develop performance measures can achieve more meaningful and useful accountability information.62

4.26

Some agencies prepare additional information to assist people to understand their performance. For example in 2018/19 Te Puni Kōkiri prepared documents to accompany its annual report, including a short A5 booklet and a folded A4 leaflet with highlights, photos, and infographics from the main report. The A5 regional summary booklet features a regional breakdown of investment spending to give whānau a view by rohe.63

4.27

Standard-setters and those that provide guidance might also need to better understand what performance means to the public and encourage public organisations to prepare and present performance information in ways that are more relevant and accessible to people.

Improve the integration and alignment of reporting

4.28

In central government, the general approach to performance reporting involves public organisations:

- setting out their strategic intentions at least once every three years; and

- reporting on a separate annual cycle that starts with the authorisation of funding and ends with reporting on what they have achieved with that funding, including their progress against their strategic intentions.

4.29

This approach provides strong visibility of, and detailed control over, a public organisation's intentions and allocated spending. However, it can also result in a fragmented performance story that explains only what individual organisations do to fund and deliver their own planned services and outcomes.

4.30

This says little about how well the public sector collectively delivers those services and outcomes, and how people receive, experience, and value them.

4.31

In our view, performance reporting should tell an integrated and aligned story that starts with what outcomes the government as a whole wants to achieve for New Zealanders. This should then be clearly reflected in public organisations' strategic intentions and operational plans.

4.32

This could involve public organisations identifying which objectives are relevant to these wider outcomes. They could then better describe how their activities, services, and outputs align with these objectives.

4.33

In our view, more time needs to be spent on defining the intervention logic between activities, services, outputs, and outcomes.

4.34

Public organisations also need to acknowledge and understand external influences that are difficult to control or attribute. They need to explain uncertainties that will affect whether they achieve their planned outcomes, particularly when a wider network of stakeholders is involved (including other public organisations, non-governmental organisations, and communities).

4.35

Technologies that bring together organisational, sector, or whole-of-government performance could help public organisations to understand and communicate that integrated story.

4.36

Insights could be found by looking at the Canadian Government's "GC InfoBase", a web-based interactive tool that summarises complex government data into simple visual stories.64 It brings together information from more than 500 government reports, including public accounts, estimates, departmental plans, and quarterly financial reports.

4.37

GC InfoBase was developed in 2013 after Canada's Parliament requested better access to information on government finances. It was also designed to meet public demand for simpler government reporting.

4.38

Agencies such as the Parliamentary Budget Officer, which provides independent analysis on the state of the nation's finances to Canada's Parliament, recognise GC InfoBase as an easy to use source of information about government spending.

4.39

The options that GC InfoBase offers for understanding the performance of the public sector and the government include an overall summary of how resources flow throughout the government, comparing the spending of public organisations, and exploring information about a specific subject, such as indigenous relations, veterans' affairs, or health.

4.40

Performance.gov in the United States of America is another example of a website that provides whole-of-government performance information. The website communicates the goals and outcomes the Federal Government is working on, how it seeks to achieve them, and how agencies are performing.65

4.41

Simply put, the performance of government and the public sector is not evident in the sum of its individual parts. Describing that performance means telling a comprehensive story about what services and outcomes are important and how public organisations, individually and collectively, use public money to provide them.

4.42

Taking a whole-of-government perspective will mean clearly demonstrating how the government's strategic ambitions connect to the individual public organisations that deliver on those ambitions.

Extend assurance and monitoring support

4.43

Auditing and monitoring functions are critical to the supply of, and demand for, good performance reporting. However, these functions are not always carried out in a way that drives improvement of performance reporting to better meet the needs of Parliament, the public, and the public organisations being monitored.

Broadening the assurance toolkit

4.44

The Public Service Act 2020 and other public sector reforms seek to encourage the public sector to be stewards of New Zealanders' intergenerational well-being.

4.45

As a result, what public sector information is considered relevant and important is also changing. For example, there are already new legislative requirements in central government for periodic well-being reports and long-term insight briefings. There is also a greater focus on baseline reviews that look at total spending and not just the marginal spending in each budget.66

4.46

Broadening the suite of assurance products and tailoring their use to where they are most beneficial might also build confidence in performance information. For instance, regular and standardised audit processes might be useful when seeking assurance about recurring allocations of funding. However, longer-term and more uncertain outcome performance might need less standardised and more targeted evaluation – performance audits are an example of this.

4.47

Sweeney argues that public sector performance audits could act as a transformational mechanism. He found that auditing performance:

… has the capacity and potential to move beyond a purely deficit-based role, to positively promote improvements and collaborative learning between institutions and stakeholders.67

4.48

However, to achieve this, performance auditing will need to become a more "proactive, collaborative, participatory activity".68

4.49

We are trying to do this in our own work. Some of our recent work has been designed to look at programmes in their early stages to provide insights to public organisations that they can act on in a timely way. Examples include our work related to the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme, the joint venture on family and sexual violence and the nationwide roll-out of the Covid-19 vaccination programme.69

Broadening the monitoring function

4.50

Not only is there evidence of a lack of clarity about the effectiveness of existing monitoring functions (see paragraphs 3.45-3.55) but two of our recent reports also highlight issues with how information about larger areas of public sector work are analysed, reported, and reviewed.

4.51

In our report Managing the Provincial Growth Fund, we found that "no clear responsibility was assigned for reporting to Parliament on the performance of the Fund's investments".70 As we mentioned in paragraph 3.30, our report Analysing government expenditure related to natural hazards found it extremely difficult to obtain a meaningful picture of what the government spends on managing natural hazards.71

4.52

The monitoring function might need to be broadened and deepened so that Parliament and the public are better able to understand public sector performance throughout regions, for specific programmes of work, across sectors, and the whole of government over the short, medium, and long term.

4.53

The monitoring function could also do more to analyse value for money and follow the money into private organisations that provide public services. We acknowledge that assessing value for money can sometimes be difficult, but we think is important to understand whether what is spent is reasonable compared to what has been achieved.

4.54

The monitoring function could also consider how well public organisations interact with Parliament and the public, and/or analyse how resilient sectors are to possible short-term shocks (such as another pandemic) or long-term changes (such as climate change).

4.55

Currently, the monitoring function focuses on public organisations within sectors. As the public sector increasingly works in a more unified and collaborative way to manage longer-term issues and outcomes, there may be value in more sector-based or outcomes based monitoring and reporting.

Build demand, co-ordinated leadership, and capability

4.56

Currently, leadership of central government's performance reporting rests somewhere between the Treasury, Te Kawa Mataaho, and public organisations. The Office of the Auditor-General, Taituarā, independent standard-setters, and other monitoring agencies also play important roles in supporting the effectiveness of performance reporting.

4.57

In our view, more co-ordinated leadership throughout the public sector is needed for the legislation, standards, and guidance to provide the right incentives to support good performance reporting.

4.58

Insights to help develop more co-ordinated leadership throughout the public sector could be found in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. This Act provides a shared vision and purpose for improving the economic, social, environmental, and cultural well-being of Wales.

4.59

The Act establishes a co-ordinated framework that shifts the focus of how public bodies plan and track what they do towards well-being outcomes at a population level and away from outputs at an organisational (performance) level.72

4.60

Although the Act allows public bodies to be flexible when setting well-being objectives, these objectives must clearly align with the contribution the public body makes to the national well-being goals. There are also clear guidelines for planning and reporting on how the public body will contribute to these national goals, the progress made, the review of that progress, and the objectives of annual reporting and assurance.73

4.61

Effective performance reporting in New Zealand needs business acumen, strategy and analysis skills, and accounting and auditing knowledge. A good understanding of internal governance practices and the legislative environment that the public organisation operates in is also needed.

4.62

Senior leaders in public organisations need to demand performance information that informs and reflects the aspirations of their organisation. If public resources are being directed and managed well, public organisations should be able to tell a clear and convincing story about how their activities and services deliver value and contribute to the outcomes that are important for New Zealand.

4.63

Committed leadership, adequate resources, and strong professional networks that continue to encourage the transfer of knowledge and best practice are all required to tell that performance story well. Public organisations might need to raise the profile of the performance reporting function and locate the function closer to strategy teams rather than accounting teams.

4.64

Above all, performance information must be meaningful and accessible if we want users to value it. For this to happen, systemic change and co-ordinated leadership throughout the performance reporting system is needed.

54: See the Te Kawa Mataaho's Kiwis Count survey at www.publicservice.govt.nz.

55: Boston, J, Bagnall, D, and Barry, A (2019), Foresight, insight and oversight: Enhancing long-term governance through better parliamentary scrutiny, Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, page 23.

56: See integratedreporting.org.

57: HM Treasury (2019), The Public Value Framework: with supplementary guidance, at www.gov.uk.

58: HM Treasury (2019), The Public Value Framework: with supplementary guidance, page 33, at www.gov.uk.

59: Historic England is a public organisation that promotes England's historic environment. See historicengland.org.uk.

60: The Policy Project is an initiative by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet that seeks to promote good policy design and development throughout the Government.

61: The Treasury (2020), Improving external performance reporting – Treasury update, page 6, at www.treasury.govt.nz.

62: Yang, C and Northcott, D (2019), "Together we measure: Improving public service outcomes via the co-production of performance measurement", Public money and management, Vol. 39, No. 4, page 253.

63: See Te Puni Kōkiri, He whakarāpopoto o ngā tūmahi ā-rohe: Regional snapshot of achievements in 2018/19.

64: The GC InfoBase can be viewed at www.tbs-gc.ca.

65: The Performance.gov website can be viewed at www.performance.gov.

66: The Treasury describes a baseline review as "a ‘deep dive' into a ministry's financial performance and is completed jointly by The Treasury and the relevant ministry. The outcome of a baseline review is to get a better understanding of the current spend, assist in assessing reprioritisations and future funding needs. It's particularly relevant to assisting the Minister of Finance in completing the annual Budget allocation." See www.treasury.govt.nz for more information.

67: Sweeney, J (2018), Beyond a deficit-based approach: Public sector audit as a transformative mechanism for positive change, PhD Thesis, London Metropolitan University, page i.

68: Sweeney, J (2018), Beyond a deficit-based approach: Public sector audit as a transformative mechanism for positive change, PhD Thesis, London Metropolitan University, page i.

69: All of these reports are available on our website at www.oag.parliament.nz.

70: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Managing the Provincial Growth Fund, page 33.

71: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Analysing government expenditure related to natural hazards.

72: Welsh Government (2016), "SPFS 1: Core guidance", Shared purpose: Shared future – Statutory guidance on the well-being of future generations (Wales) Act 2015, page 14.

Welsh Government (2016), "SPFS 2: Individual role", Shared purpose: Shared future – Statutory guidance on the well-being of future generations (Wales) Act 2015, page 4.

73: Welsh Government (2016), "SPFS 2: Individual role", Shared Purpose: Shared Future – Statutory guidance on the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, pages 3, 4, and 7.