Part 1: Introduction

1.1

Performance reporting is the main way that public organisations explain to Parliament and the public how well they have used public money to deliver services and achieve outcomes, and ultimately create value for New Zealand.

1.2

Therefore, effective performance reporting plays an important role in maintaining public trust and confidence in the public sector and the government. This is important for our representative democracy.

1.3

In this Part, we explain:

- what we mean by performance reporting;

- why we are writing this paper;

- the purpose of this paper; and

- our research approach.

What is performance reporting?

1.4

Performance in the public sector can often be a "blurry, elusive concept".1 Sometimes, performance just means how well something is done.

1.5

When we use the term "performance", we mean how well public organisations make the best use of public money and resources to achieve certain objectives.

1.6

Reporting on that performance is a critical part of the process of providing effective public accountability.2 Performance reporting provides the building blocks for demonstrating the competence, reliability, and honesty of the public sector to Parliament and to the public. It is also fundamental to good management, governance, and decision-making.

1.7

In line with statutory obligations, public organisations must report annually to Parliament and the public on their performance as part of a regular performance management cycle.

1.8

Explaining performance includes describing:

- how an organisation spends money on necessary resources (such as people or equipment);

- how it uses those resources to deliver services or other outputs (such as elective surgery or improved road signs); and

- how those services or outputs impact on planned outcomes (such as healthier communities or safer roads).

1.9

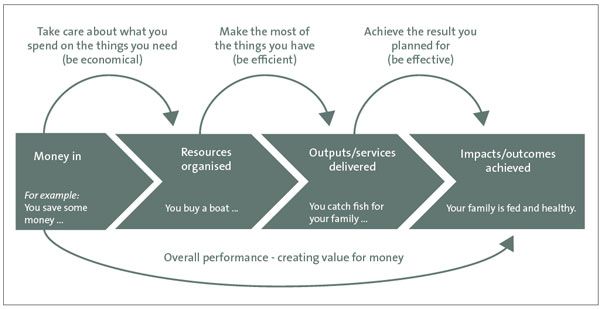

Figure 1 shows a common model of bringing these steps together to explain and account for performance.3 Each step assesses different dimensions of performance – the economy of using resources, the efficiency of delivering outputs, and the effectiveness of generating outcomes.4

1.10

In this model, overall performance is a combination of these three dimensions. It is about understanding whether the money spent (economically) on delivering services (efficiently) to achieve the desired outcomes (effectively) has resulted in value for money.

Figure 1

A common approach to describe and report performance

Source: Adapted from Pollitt

1.11

The model described in Figure 1 is useful for explaining and accounting for the performance of an organisation with resources, outputs, and outcomes that:

- are controllable;

- are easily and clearly defined; and

- have few external influences.

1.12

However, this production-line model of performance has limitations.5 By itself, it cannot always capture the full range of public sector activities or the attributes that Parliament and the public look for in the public sector's performance. For example, the model is not well suited to describing the performance of networks of organisations and people who, to meet complex social challenges, need to deliver shared outcomes.6

1.13

The model cannot always demonstrate whether an organisation (and its employees) has behaved in the way the public might expect. It cannot help to describe whether an organisation has acted respectfully, fairly, honestly, and with integrity or whether it has worked collaboratively and is inclusive.

1.14

The model also does not describe whether an organisation's outputs, services, or outcomes:

- are the right ones;

- have public support;

- are resilient to shocks (such as a pandemic); or

- are sustainable over time.

1.15

In our view, the wider attributes set out in paragraphs 1.12-1.14 are all fundamental to describing public sector performance. Reporting these clearly helps a public organisation to effectively demonstrate its trustworthiness and how well equipped it is to be a long-term steward of public resources. Stewardship is about how the public sector works and behaves for the long-term benefit of the public, not just about what services it delivers.

1.16

Another approach to reporting performance that tries to incorporate some of these wider attributes of public sector value or success was proposed by the Auditor-General in 2002. This model included:

- the results a public organisation achieves (including any impacts on communities);

- the level and quality of a public organisation's interactions with the public (including ethical behaviours); and

- the costs associated with these results and interactions.7

1.17

Another example of an alternative approach is the Public Value Framework that Her Majesty's Treasury in the United Kingdom developed in 2019. This framework redefines what value for money means to a government department and how it should be reported.

1.18

Rather than focusing on quantifying inputs and outputs, the Public Value Framework measures success by how a public organisation pursues and monitors its overall goals, manages its financial inputs, supports long-term sustainability, and engages with people to understand their needs and gain their support. We discuss this model in more detail in Part 4.

The purpose of our work

1.19

The public's trust and confidence in the public sector and the government is an important foundation of our democracy. To help build and maintain that trust, the public sector needs effective public finance, management, and accountability systems. These systems need to be cohesive and mutually reinforcing.

1.20

Today, these systems are undergoing significant change. Increased public expectations and a range of reforms are shifting the way the public sector thinks and works. Some reforms focus on supporting the public sector to work in ways that can better serve people and, in doing so, support a broader range of intergenerational well-being outcomes.

1.21

In our view, the information that the public sector uses to understand and manage its performance – and that is used to hold it to account – is of central importance to meeting these objectives.

1.22

We continue to have a strong interest in improving performance reporting and, in turn, helping to improve public sector performance and accountability. We also play an important role in improving performance reporting through our independent audit work, Controller function, and support of Parliament's scrutiny.

1.23

This paper builds on our recent research about the future of public accountability. It considers performance reporting in its entirety – from collecting information to its reporting and use. Although this paper primarily focuses on performance reporting for public accountability purposes, we also consider, where relevant, the implications of this reporting for effective governance and management in public organisations.

1.24

The main purpose of this paper is to provide insights into how the public sector can improve its approach to reporting performance in a way that is useful to Parliament and to the public. A secondary aim is to inform our own thinking about our role and how we can better support improvements to performance reporting.

Our approach

1.25

This paper draws from a mix of qualitative and quantitative research. We collected information about the annual reporting process by analysing annual reports, interviewing staff at public organisations, reviewing auditor findings, and looking at other related research.

1.26

Our work also considered findings from two recent discussion papers we have published: Public accountability: A matter of trust and confidence and Building a stronger public accountability system for New Zealanders.8

Analysing annual reports

1.27

To help us understand performance reporting from a reader's or user's perspective, we analysed performance information from the annual reports of 33 public organisations that were published between 2016 and 2018.

1.28

The annual reports we looked at came from a range of sectors, including health, education, transport, justice, and local government.

1.29

We recently developed a database of performance data from the annual reports of about 300 public organisations from 2016 to 2019. We have also drawn on this resource to help inform this work.

1.30

It is important to note that drawing broad conclusions from this data is difficult because of its uniqueness and changeability. A degree of judgement is needed when interpreting how some annual reports describe and present performance information.

Interviews with staff of public organisations

1.31

To help us understand the public sector's perspective, we interviewed a small number of senior officials from public organisations in a range of sectors. Their responsibilities included preparing annual reports and monitoring other public organisations.

1.32

The interviews were semi-structured. We asked questions about the challenges and opportunities that people experienced when developing and using performance frameworks, operating in the planning and reporting cycle, and monitoring other public organisations.

1.33

We used the findings from these interviews to collate common themes that reflected the strengths and weaknesses of the performance reporting and monitoring processes.

Reviewing audit findings on performance reporting

1.34

Our annual audits of public organisations routinely assess the appropriateness of service performance measures and verify the reported results.

1.35

To help us understand the auditor's perspective on performance reporting, we reviewed the main findings from our audits of 51 public organisations in a range of sectors from 2015 to 2018. We chose the public organisations based on their size, their representation of different sub-sectors, and geographical spread.

Other research

1.36

To understand the perspectives of other commentators on this topic, we reviewed research and studies about the quality of performance reporting in the public sector. These included publicly available reports and papers from the Productivity Commission, private sector consultants, and academics.

1.37

We also looked at the different approaches that New Zealand and international public organisations are taking to performance reporting. We also reviewed the many previous reports about performance reporting and public accountability that we have published.

Scope and limitations

1.38

Although this research draws on several sources, the qualitative and quantitative data we have gathered represents a sample only of the total population of each of these sources.

1.39

The Auditor-General does not comment on government policy except to review how well particular policies are implemented (for example, their effectiveness and efficiency). Therefore, because the options to improve the system of performance reporting are mostly matters of government policy, this paper is limited in what it can say about these.

1.40

When we discuss options for improvement, we present a range of examples, some of which are from public organisations in New Zealand. The examples are intended to illustrate different approaches and do not represent a view by the Auditor-General that these constitute best practice.

1: Summermatter, L and Siegel, JP (2009), Defining performance in public management: Variations over time and space, paper for International Research Society for Public Management XXIII conference, Copenhagen, 6-8 April 2009, pages 3 and 19. For an overview of the complexities in defining performance, see Ghalem, Â, Okar, C, Chroqui, R, El Alami, S (2016), Performance: A concept to define!, Logistiqua Conference, Morocco.

2: See Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Public accountability: A matter of trust and confidence at oag.parliament.nz.

3: Smith notes that Pollitt was one of the first to conceptualise this model. See Smith, S (2014), Performance management as ritual in the New Zealand public sector, Doctoral thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology, page 28. Also see Pollitt, C (1986). Beyond the managerial model: the case for broadening performance assessment in government and the public sector. Financial Accountability and Management. 2(3).

4: Productivity is another measure to help describe performance. It is measured by the rate of outputs per unit of inputs.

5: See Smith, S (2014), Performance management as ritual in the New Zealand public sector, Doctoral thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology, pages 28, 29, and 37.

6: See Vitalis, H and Butler, C (2019) "Organising for complex problems – beyond contracts, hierarchy and markets", presentation at the XXIII International Research Society for Public Management Annual Conference.

7: Office of the Auditor-General (2002), Reporting public sector performance, pages 5-6.

8: See our website at oag.parliament.nz.