Part 1: Councils' performance in 2019/20

1.1

In this Part, we consider the main financial performance trends of councils for 2019/20.1 We comment on the revenue recorded by councils, the operating expenditure incurred by councils, whether councils are processing building consent applications within the statutory time frames, and whether aspects of councils' non-financial performance for 2019/20 were affected by Covid-19.

1.2

To carry out our analysis, we compared 2019/20 actual reported figures with what councils planned and included in their budgets.2

1.3

Overall, the revenue received by councils in 2019/20 from core revenue sources (such as rates, subsidies, and grants) was as expected and in line with what had been budgeted for.

1.4

Councils did incur higher than forecast operating expenditure. From our analysis, there were no consistent reasons for this. However, we have noted that liabilities from leaky home claims is a long-standing issue that continues to have significant expenditure implications for at least two councils.

1.5

Covid-19 directly affected council services that were required to close during Alert Levels 3 and 4. However, based on the information included in councils' annual reports, other council operations were not as affected by Covid-19.

Revenue recorded by councils

1.6

Councils recorded total revenue of $13.9 billion for the 2019/20 year (2.8% higher than the $13.6 billion budgeted). Excluding Auckland Council, councils recorded total revenue of $8.8 billion, which was 4% higher than councils had forecast ($8.4 billion).

1.7

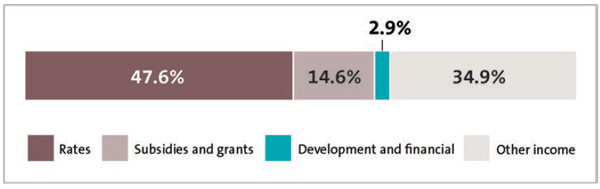

Figure 1 shows the categories of revenue for councils for the 2019/20 year.

Figure 1

2019/20 actual revenue, by sub-category

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

1.8

The proportion of revenue recognised by councils was similar to the previous financial year.

1.9

Of the total revenue in 2019/20, $6.6 billion was from rates. This was largely consistent with the amount councils planned to collect and equates to 47.6% of the councils' total revenue. In 2018/19, rates were 46.7% of the councils' total revenue.

1.10

The revenue received by councils was not significantly affected by the nationwide lockdown in response to Covid-19, although we note that individual councils would have been affected in different ways. For example, Hurunui District Council had a decrease in revenue because the Hanmer Springs Thermal Pools and Spa could not operate during Alert Levels 3 and 4.

1.11

We note that councils faced public pressure to keep rates increases down in the 2020/21 financial year to assist ratepayers facing financial hardship because of the disruptions of Covid-19.3 As a result, many councils reconsidered planned rates rises and consulted with their communities on options to keep rates down. Councils also considered other options to provide targeted assistance to ratepayers that needed it, including revised rates remission, postponement policies, and lower rate penalties.

1.12

We found that revenue other than rates was largely as planned. Subsidies and grants received by councils was $75 million (3.8%) higher than budgeted.

1.13

In previous years, most subsidy income has been received from Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency. More recently, councils have had access to other grants, such as the Provincial Growth Fund, some tourism funds, and the Government's "shovel-ready" funding.

1.14

Christchurch City Council had a significant increase (85%) compared with budget in subsidies and grants, largely because it received $81 million of grants from the Crown's Christchurch Regeneration Accelerator Fund to accelerate Canterbury's earthquake recovery. This was not budgeted for.

Operating expenditure of councils

1.15

Councils incurred higher than forecast operating expenditure. The total operating expenditure for all councils was $12.5 billion, which was a $626 million (5.3%) increase compared with planned expenditure of $11.9 billion. When Auckland Council is excluded from these results, councils incurred total operating expenditure of $8.1 billion compared with a budget of $7.6 billion.

1.16

Figure 2 shows the main categories of councils' operating expenditure.

Figure 2

2019/20 budget and actual operating expenditure, by sub-category

| Operating expenditure | 2019/20 Actual $million | 2019/20 Budget $million | Expense as a proportion of total actual operating expenditure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depreciation and amortisation | 2,661.9 | 2,638.4 | 21.3 |

| Employee costs | 2,765.9 | 2,679.0 | 22.2 |

| Finance costs | 806.7 | 867.6 | 6.5 |

| Other operating expenditure | 6,247.2 | 5,670.4 | 50.0 |

| Total | 12,481.7 | 11,855.4 | 100.0 |

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

1.17

Employee costs for all councils increased by 3.2% to $2.8 billion compared with a budget of $2.7 billion. In our work, we often hear about the challenges councils face in recruiting and retaining skilled staff, particularly regulatory and engineering staff. We will continue to monitor and report on this.

1.18

Other operating expenditure was 10% higher than budgeted. From our analysis, there were no consistent reasons for this.

1.19

Two councils, Auckland Council and Tauranga City Council, had higher operating expenditure compared to budget due to increased operating expenses for the remediation of weathertightness and associated building defects.

1.20

Liabilities from leaky home claims is a long-standing issue that continues to have significant implications for Auckland Council in particular. This issue is complex due to uncertainty and the various stages of legal proceedings. As a result, it is difficult for councils to budget for. We first reported on council's exposure to liabilities from leaky home claims in our report Local government: Results of the 2006/07 audits.4

1.21

Tauranga City Council reported $30.6 million in weathertightness settlements in 2019/20. This was a significant increase for the Council as no settlement had occurred in the previous year. Because of the complexity of the settlements, these have a high degree of uncertainty when setting the budget. Tauranga City Council also reported other losses of $35.7 million. This included asset impairments for the Harington Street carpark building, which did not meet the required standard of seismic resistance ($19.8 million), and the Bella Vista site remediation ($9 million).

1.22

Auckland Council notes in its annual report that the costs of weathertightness settlements are not budgeted for because of the uncertainty of a provision for the remediation of weathertightness and associated building defect claims (as well as the remediation for the management of contaminated land and closed landfills). Auckland Council's provision for remediation of weathertightness claims increased by $86 million as a result of the high costs associated with multi-unit claims. The contaminated land and closed landfills provision mainly increased by $17 million due to an increase in climate change coastal adaptation costs associated with closed landfills.5

1.23

Another reason for Auckland Council's increased operating expenditure was an unbudgeted $10 million that the Auckland Emergency Management Team spent on Covid-19 relief, including the delivery of food parcels and household goods during the nationwide lockdown period.6 Additional expenditure for Covid-19 relief might also have been incurred by other councils, but this level of detail was not in their annual reports.

Building consents

1.24

Councils have a statutory requirement to process most building consent applications within 20 working days (this applies to 67 out of the 78 councils as the 11 regional councils do not process building consents). As part of the audit of councils' non-financial performance, our auditors often look at how councils meet this requirement. This timeliness requirement can also be used as an indicator of councils' effectiveness in responding to growth.

1.25

In 2018/19, we reported that most councils did not meet the statutory time frames for processing building consent applications.7

1.26

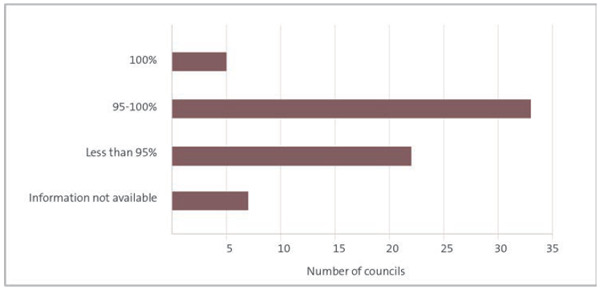

In 2019/20, building consent performance data was available for 60 councils (2018/19: 60). Of the 60 councils, five reported that they had processed 100% of building consent applications within 20 working days (Figure 3),8 which is the statutory requirement (in 2018/19, eight councils reported that they had processed 100% of building consent applications in that time frame). Thirty-three councils reported they had processed between 95% and 100% of building consent applications within the time frame (2018/19: 34), and 22 councils reported that they processed fewer than 95% (2018/19: 18). We did not find usable information about building consent timeliness in seven councils' annual reports.

Figure 3

Councils' processing of building consent applications within 20 working days in 2019/20

Source: Collated from 60 councils' annual reports.

1.27

This indicates a decline in performance in 2019/20 compared with 2018/19, with fewer councils processing all building consent applications within 20 working days and more councils processing fewer than 95% of these applications within the statutory time frame.

1.28

We could reasonably expect fewer building consent applications to have been processed during the latter half of the 2019/20 financial year as a result of Covid-19 and the economic slowdown. This might have presented an opportunity for those fewer applications to have been processed more quickly. However, this does not take account of the nature or complexity of the applications, or whether councils' other activities took priority over building consent processing post-lockdown.

1.29

Of the five councils that processed 100% of building consent applications within the statutory time frame, only one (Waimakariri District Council) is classified as a high-growth council under the National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity 2016 (see Appendix 1).9 This means that most high-growth councils are not meeting the statutory time frame for processing building consent applications.

1.30

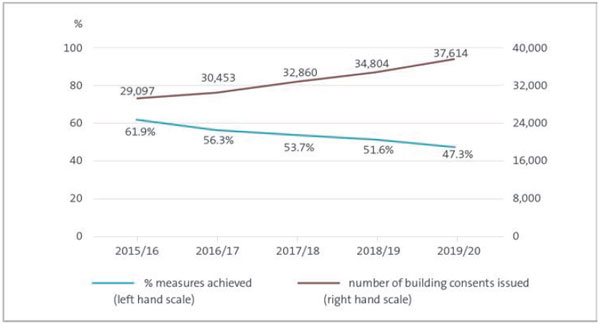

Timeliness is one of the measures used to assess councils' performance in relation to building consents. These measures are generally shown as either "achieved" or "not achieved" in councils' annual reports. Trend analysis of councils' performance across all building consent measures shows a steady decline from 61.9% achieved in 2015/16 to 47.3% achieved in 2019/20 (Figure 4). The decrease of 4.3% from 2018/19 to 2019/20 is larger than the 3.4% average decrease per year from 2015/16 through to 2018/19. Given that performance has been declining since 2015/16, Covid-19 cannot be the principal reason for this, in the years up to and including 2018/19.

Figure 4

Percentage of all building consent performance measures achieved and the total number of building consents issued for new dwellings, 2015/16 to 2019/20

Source: From information collected from councils' annual reports and Statistics New Zealand.

1.31

Figure 4 shows that the total number of building consents issued has increased steadily from 29,097 in 2015/16 to 37,614 in 2019/20. Overall, the percentage of performance measures achieved has decreased over the same period. However, this might not represent a direct causal relationship and there could be other factors contributing to fewer building consent performance measures being achieved over time.

1.32

We encourage all councils to investigate their performance. In our view, high-growth councils in particular need to consider what effect this could have on their ability to support growth in their communities.

Levels of service were not significantly affected in 2019/20 as a result of Covid-19

1.33

Because of the disruption caused by Covid-19, we looked at whether the performance information reported indicated a decline in the levels of service provided by councils in 2019/20.

1.34

Our analysis did not indicate any consistent decline in the levels of service provided by councils. This was because many of the services provided by councils are essential services that continued despite New Zealand moving into a nationwide lockdown during the financial year.

1.35

However, some services were affected. For example, there was a drop in the percentage of performance measures achieved in respect of libraries in 2019/20. Between 2015/16 and 2018/19, the percentage of performance measures achieved in respect of libraries were relatively stable, dropping from 74.6% in 2015/16 to 70.2% in 2018/19. In 2019/20, this dropped to 54.0%. This is not unexpected, given that libraries were closed for part of the 2019/20 financial year during Alert Levels 3 and 4.

1: For 2019/20, draft financial information for five local authorities was included in our analysis because the audited financial information was not available at the time we undertook our analysis. Five councils missed the revised deadline to complete and adopt their audited annual report by 31 December 2020. Paragraphs 3.4-3.9 of this report provide more information.

2: We looked at individual council figures, except for Auckland Council where group level figures were used, because the council-controlled organisations of Auckland Council provide core services such as public transport, roading, and water services. Budget information is as reported in councils' 2019/20 annual reports.

3: Local Government Covid-19 Response Unit (August 2020), Local government sector COVID-19 financial implications, Report 3 – Comparison of 2020 annual plan budgets against long-term plans, page 10.

4: Office of the Auditor-General (2008), Local government: Results of the 2006/07 audits, Part 10, page 69.

5: Auckland Council (2020), Auckland Council Annual Report 2019/20, Volume 3, page 31.

6: Auckland Council (2020), Auckland Council Annual Report 2019/20, Volume 3, page 31.

7: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Insights into local government: 2019, Part 3.

8: These councils were Horowhenua District Council, Ruapehu District Council, Stratford District Council, Waimakariri District Council, and Waitomo District Council.

9: Two provincial and three rural councils met the statutory time frame.