Part 3: Responding to growth: Consenting development

3.1

In this Part, we look at information in councils' annual reports on building and resource consenting decisions, and statistical information on recent sector trends. We also look at narratives from some councils' annual reports about their consenting operations to understand their performance and the reasons they give for it.

3.2

Managing growth is a challenge for many councils. Responding to growth pressures for housing, associated infrastructure, community facilities, and services is complex, time critical, and expensive. We acknowledge that councils are often the last resort for liability claims when things go wrong.

3.3

We regularly comment on infrastructure challenges in our reports on the local government sector, including this report. The Productivity Commission's 2019 report Local government funding and financing noted that growth is one of the most significant challenges councils face.

3.4

A particular challenge is supplying enough infrastructure for urban growth. The Commission said that “[t]he failure of high-growth councils to supply enough infrastructure to meet housing demand is a serious problem”.

3.5

Ineffective development planning and consenting are regularly raised as reasons for excessive development costs and delays, particularly to housing development.

3.6

Most councils did not meet the statutory time frames for processing building consent applications and non-notified resource consent applications, although many came close.

Council responsibilities

3.7

Councils have primary responsibility for planning and regulating land use and building under the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Building Act 2004.

3.8

Councils have a statutory requirement to process most building consent and non-notified resource consent applications within 20 working days.10 As part of the audit of councils' non-financial performance, our auditors often look at how councils meet this requirement.

3.9

Meeting timeliness requirements for building and resource consent applications is only an indicator of councils' effectiveness in responding to growth. The information contained in councils' annual reports does not give a measure of the quality of the development proposals, decision-making, or planning. We also recognise that speed and cost are indicators of efficiency but not necessarily indicators of regulatory quality or value for ratepayers.11

3.10

In addition to planning for growth and consenting, councils are exposed to liabilities from regulatory and implementation failures. Weathertightness claims continue to be significant.

3.11

It takes only one failure to result in a significant cost to ratepayers. For example, the Bella Vista development in Tauranga, where the near-completed housing development was found to have serious structural and geotechnical defects.

3.12

Tauranga City Council ultimately purchased the site developed by Bella Vista. The Council is currently in a public tender process to re-sell the site for development to cover the cost of its purchase. The cost to ratepayers, not including the Council's insurance proceeds, is currently more than $3.5 million.12

3.13

Councils also meet the costs of policing (and prosecuting) unconsented and unlawful activity. Councils are also often the last resort for meeting liability claims, even where others are partly or fully responsible, creating an incentive to be cautious.

Performance of regulatory functions: Building and resource (land-use) consenting

3.14

Typically, councils have a target to process 100% of consent applications within 20 working days, but we did see some variations. For example, Hutt City Council had a target to process 80% of building and resource consent applications within 18 working days, and Rotorua Lakes Council had a target to process 60% of building and resource consent applications within 15 working days. Other councils had targets of less than 100% in 20 working days, which is not consistent with statutory obligations.

3.15

New or substantive building works often require a building consent but not a resource consent. Therefore, councils usually process more building consent applications than resource consent applications.

3.16

We looked at annual report information for building consent applications and non-notified resource consent applications for 67 territorial and unitary authorities. We did not look at notified resource consent applications, because these are usually complex and take more than 20 working days to process.

3.17

Regional councils also process consent applications for matters in their areas of responsibility, including major earthworks to do with buildings. We did not include these applications, because they are a minority and are not usually substantive for approving building developments.

Building consent delivery performance

3.18

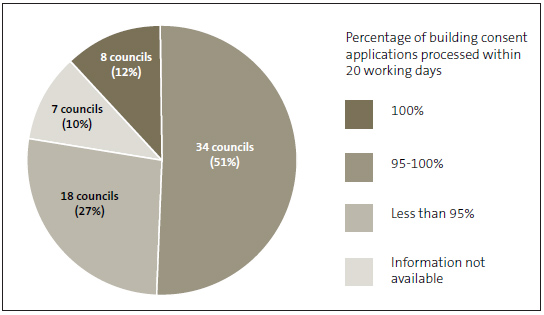

Eight councils reported that they had processed 100% of building consent applications within 20 working days, which is the statutory requirement.13 Thirty-four councils reported that they processed between 95% and 99% of building consent applications, and 18 councils reported that they processed fewer than 95%. We did not find usable information about the processing of building consent applications in seven councils' annual reports.

Figure 3

Building consent applications processed by councils within 20 working days in 2018/19

In 2018/19, eight of 60 councils reported that they processed 100% of building consent applications within 20 working days, which is the statutory requirement. Thirty-four councils processed between 95% and 99% of building consent applications within 20 working days. Eighteen councils processed fewer than 95% of building consent applications within 20 working days. We could not find usable information on building consent timeliness for seven councils.

Source: Collated from 67 councils' annual reports.

3.19

Invercargill City Council (which processed 64% of building consent applications) remarked on a significant increase in the number and value of building consent applications compared to the previous 12 months. It also stated that "resources (both internal and external) had been insufficient to meet the demand. This increase in applications is a nation-wide trend, as is the shortfall in qualified staff".14

3.20

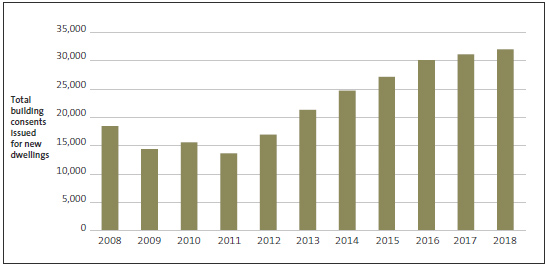

Statistics New Zealand reports increasing numbers of building consents issued, mainly for housing, which has been sustained since 2012/13.15

Figure 4

Total building consents issued for new dwellings, 2008-18

In 2018, all councils issued more than 30,000 consents for new dwellings. In 2011, all councils issued fewer than 15,000 consents for new dwellings. The graph shows a steady increase in consents issued between 2011 and 2018.

Source: Statistics New Zealand.

3.21

Statistics New Zealand recorded that Auckland Council processed 14,956 building consent applications in 2018/19, which is 37% of all building consent applications (40,855). Only five other councils processed 1000 or more consent applications: Christchurch City Council (2746), Hamilton City Council (1696), Tauranga City Council (1375), Queenstown-Lakes District Council (1364), and Wellington City Council (1016).

Resource consent delivery performance

3.22

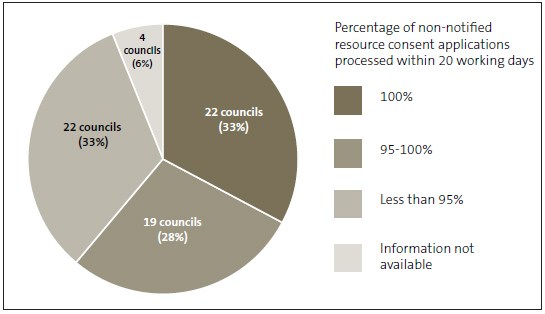

For non-notified resource consent applications, 22 of the 67 councils reported that they processed 100% of them within 20 working days. Nineteen councils reported that they processed between 95% and 99%, and 22 councils reported that they processed fewer than 95%. We did not find usable resource consent application processing information in four councils' annual reports.

Figure 5

Non-notified resource consent applications processed by councils within 20 working days in 2018/19

In 2018/19, 22 of 63 councils reported that they processed 100% of non-notified resource consent applications within 20 working days, which is the statutory requirement. Nineteen councils processed between 95% and 99% of non-notified resource consent applications within 20 working days. Twenty-two councils processed fewer than 95% of non-notified resource consent applications within 20 working days. We could not find usable information on resource consent timeliness for four councils.

Source: Collated from 67 councils' annual reports.

3.23

Auckland Council reported that it processed 56% of non-notified resource consent applications within 20 working days. Auckland Council said:

The disappointing results … continue to underline the complex and challenging consent environment bought about by an enabling Unitary Plan and the significant number of complex commercial, and residential apartment and terrace housing developments driven by growth.16

3.24

In 2017/18, Auckland Council received a modified audit opinion on the statement of service performance in its annual report for building consent and non-notified resource consent applications. This was because of inaccuracies in how it recorded processing times for these performance measures.

3.25

Central Hawke's Bay District Council (which processed 60% of building consent applications) remarked in its annual report17 that resource shortages and a dramatic increase in the number of consent applications had led to it exceeding "... time limits in many cases. Most cases where limits were exceeded were only by a number of days."

Consenting costs

3.26

We looked at council schedules of fees and charges, including deposit fees and charges for processing residential building and resource consent applications. We found that both thresholds and schedules of costs varied widely. Some councils specified a deposit fee, and others specified hourly rates only. This is not an unexpected finding, and reflects that councils have their own circumstances and policy approaches to setting fees.

3.27

For example, Auckland Council charged a building consent application deposit fee of $1,766 (for 60% of building consent applications processed), while Christchurch City Council charged $6,840 (for 99% of building consent applications processed). Waimakariri District Council charged a $164 hourly rate for processing building consent applications, while Queenstown-Lakes District Council charged a $272 hourly rate. Nelson City Council charged a non-notified resource consent application deposit fee of $1,300, while its neighbour, Tasman District Council, charged a $950 fee.

Implications for growth

3.28

Information in councils' annual reports does not clearly explain the inter-relationship between consenting performance and outcomes, nor how consenting timeliness relates to development and growth. Annual reports also do not record how long councils took to process applications where the time taken exceeded 20 working days nor, in most cases, what efforts they made to solve staff shortages. These concerns are about more than timeliness – they create risks for quality and compliance.

3.29

It seems reasonable to expect that pressures on consenting authorities will continue. It is not possible, from the information in annual reports, to understand the full effect that consenting performance has in responding to growth pressures. The information in annual reports also does not fully describe how building and resource consent requirements and conditions affect the cost, time, or location of development.

3.30

Building and resource consenting are matters of interest to communities as well as to applicants, and enable significant economic activity. We encourage councils to present meaningful numerical and narrative information about consenting performance and circumstances in their annual reports.

3.31

In this way, applicants, regulators, communities, and other stakeholders get better insights into their council's circumstances and any steps it is taking to respond to pressures and improve its performance.

10: The statutory days exclude days where the applicant provides further information or the processing end date has been extended.

11: However, other organisations do assess regulatory quality and value. For example, International Accreditation New Zealand does biannual assessments of building consent authorities to check that they have, and consistently and effectively implement, the minimum policies, procedures, and systems a building consent authority must have to perform building control functions.

12: Tauranga City Council press release, (6 December 2019), "Tauranga City Council sells 22 properties" at tauranga.govt.nz.

13: These councils are Kāpiti Coast District Council, Kawerau District Council, Ruapehu District Council, South Wairarapa District Council, Upper Hutt City Council, Waipa District Council, Wairoa District Council, and Whanganui District Council.

14: Invercargill City Council (2019), Annual Report 2018/19, page 51.

15: See Statistics New Zealand (2019), "Building consents issued: June 2019", at www.stats.govt.nz.

16: Auckland Council (2019), Auckland Council Annual Report 2018/19 Volume 1, page 99.

17: Central Hawke's Bay District Council (2019), Annual Report 2018-19. page 29.