Chapter 5: Systems focus and lessons from Whānau Ora and collective impact

5.1 Systems focus on family violence, sexual violence and child abuse

5.1.1 Systems thinking approach

A ‘wicked problem’ requiring a sophisticated solution

The complexity and interconnectedness of family violence, sexual violence, child abuse and other social issues mean they can be regarded as ‘wicked problems’, a term coined by Rittel and Webber (Carne et al., 2019, pp. 8–10). Wicked problems can be described as:

… complex, multifaceted and enduring. They have multiple drivers, are hard to describe and don’t have one right answer. Many stakeholders are involved with different viewpoints, norms and priorities. Additionally, the effectiveness of specific interventions are hard to evaluate because of downstream effects and the inherent complexity of the issue, making it difficult to identify direct links of cause and effect. (Carne et al., 2019, p. 8.)

Many of the studies reviewed in this report agree that the complexities of family violence, sexual violence, and child abuse need a sophisticated approach because no one intervention, agency, initiative or piece of legislation can solve this ‘wicked problem’ (Allen & Clarke, 2017; Carne et al., 2019; Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2016, 2017; Foote et al., 2014, 2015; Herbert & MacKenzie, 2014; Lambie & Gerrard, 2018; Rees, Boswell, Appleton-Dyer, 2017; Taylor et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the interconnections between types of violence mean they need to be addressed together (Carne et al., 2019; Lambie & Gerrard, 2018; Taylor et al., 2014; The Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2017). Rees and colleagues (2017, p. 6) state that:

Tackling these different forms of violence independently of the others, ignores their overlapping causes and the underlying set of factors that can protect people and communities. It is important therefore, if we are to be more successful at addressing violence in all its forms, that we understand this system of interconnected factors.

Transformative change – Systems thinking approaches

The paper by Carne, Rees, Paton, Fanslow and Campus (2019) Using systems thinking to address intimate partner violence and child abuse and neglect in New Zealand provides a good overview of systems thinking (ST) approaches and tools, and how they could be applied to develop a holistic response.

Carne et al. (2019, p. 3) describe ST as:

… a way of seeing the world that provides a language to communicate and investigate complex issues. While ST includes a number of theoretical and practical approaches, they share a common focus on understanding the factors affecting an issue and how they are connected to each other in a system: a set of things working together as a complex whole.

ST tools and approaches provide a way of co-designing, sharing understandings, monitoring and evaluating a more holistic family violence system (Carne et al., 2019; Foote, Carswell, Wood & Nicholas, 2015). Foote et al. (2015) used systems tools to prototype a method for measuring the effectiveness of a ‘whole-of-system’ response to family violence. They identified that the benefits of a systems approach are that it:

provides a set of ideas and tools to make the ‘whole system’ visible and discussable, and enables those involved in setting policies and investment priorities the ability to learn about what will shift the behaviour of the family violence prevention system towards desired outcomes. (Foote et al. 2015, p. 6.)

Foote and colleagues note ‘there is a high degree of uncertainty about the effectiveness of government investment in response to family violence. There is a general lack of strong evidence about “what works, what doesn’t and why”. Also, there is no unique, uncontested measure of effectiveness’ (Foote et al. 2015, p.10).

Authors note that, although there has been some progress in understanding the effectiveness of certain programmes and interventions, there is a lack of capability within government agencies to engage and use system approaches. Carne and colleagues (2019) make the point that the concepts of ST and service integration are often confused and conflated:

With respect to the service ‘system’ responding to IPV and CAN, there is much talk about integration of services, including terms such as: integrated system, integrated programme, integrated response model, integrated service response, integrated practice and integrated community practice. Likewise, most of the literature relating to service systems and IPV and CAN refers to service integration and does not actually include systems thinking, methods, or tools. (Carne et al., 2019, p. 13.)

5.1.2 Analysis of current ‘family violence system’

Several studies have examined the current state of the family violence system to identify what is required to improve the system for families and whānau. An analysis by Foote, J., Taylor, A., Nicholas, G., Carswell, S., Wood, D., Winstanley, A., et al. (2014) for the Glenn Inquiry assessed New Zealand’s response to family violence and child abuse as like a patchwork. Their analysis was based on the People’s Inquiry (2014), which involved 500 public responses to the question ‘If NZ was leading the world in addressing child abuse and domestic violence, what would that look like?’ They also held workshops with practitioners, sector experts and researchers, who reported New Zealand’s response was of:

- variable quality;

- variable resourcing;

- insufficient coordination;

- poor levels of evaluation and evidence to support some approaches;

- insecurity of funding;

- lack of national strategy;

- contracting, funding and accountability processes that can undermine service delivery.

Allen and Clarke’s (2017) study of the family violence service system for the Ministry of Justice interviewed 171 participants, including families and whānau effected by family violence, government and community service providers and family violence experts. Their recommendations echo the concerns identified in the Glenn Inquiry and focus on a more integrated, holistic and well-resourced service system:

- The current system needs to move from being crisis-driven to focussing on long-term wellbeing. This will require a greater focus on primary prevention targeting young people and the general population, and longer-term support for families and whānau accessing services.

- Assessment and interventions need to be integrated and holistic. This could be in the form of a ‘hub’ model with co-located services, and will require navigation and advocacy services that are not limited to cases that are deemed ‘high risk’ or ‘complex’.

- Support needs to be whānau-centred, in that it needs to be provided to all members of the family and whānau at the same time (although not necessarily through the same provider or at once). Families and whānau should also be the key decision-makers in determining their own journeys to wellbeing.

- Services need to be more flexible in terms of the way that they are funded and provided. A one-size-fits-all approach will not work, and support needs to be individualised and culturally relevant. This includes incorporating flexibility into eligibility criteria for client funding, and moving towards outcomes-based contracting of services (which will require a greater focus on monitoring and evaluation).

- Communities must be empowered to drive the process of addressing family violence. Local input into designs is vital to ensure that services are successful in the large variety of local contexts and environments across New Zealand.

Lambie and Gerrard’s (2018) discussion paper on preventing family violence in New Zealand also promotes the need for more prevention and early intervention, particularly given the life-long impacts of family violence and child abuse on children. They also point to the need for workforce capacity and capability to be enhanced in terms of trauma-informed care, and for more research and evaluation to identify emerging and promising practices as discussed in the previous chapter.

Carne, Rees, Paton, Fanslow and Campus (2019, p. 12) summarise the calls to take a systems approach to intimate partner violence and child abuse by the Family Violence Death Review Committee, the Glenn Inquiry, the Impact Collective, and the New Zealand Productivity Commission:

- The current family violence service ‘system’ is a system by default and not a system by design. It was not developed to account for the intersection of IPV and CAN and concurrent social issues that may exist (e.g. trauma, mental health issues, addiction, poverty)

- Many services and service delivery models have been unchanged for years without being evaluated. Likewise, agencies generally have little information about which interventions and services work well and for whom, and which do not work well and why

- Without clarity about interconnections across the system, attempting to fix one part of a complex system in isolation can reveal or create unexpected further problems downstream and/or be unsafe

- There is little ability or incentive for providers to experiment and share or adopt innovations. (This is partly related to low levels of funding of non-government organisations and highly prescribed contracting by agencies.)

- Services can be disempowering for clients allowing them little participation in decisions. There is often poor coordination between services, and clients often find government processes confusing, overly directive and/or harmful (exposing victim/survivors to further violence) as well as wasteful and disconnected

- Responses can be inappropriately confined to one-off single-issue interventions. Opportunities for early intervention with potential to avoid further escalation or harm are frequently missed. The current system means that both human and fiscal costs escalate as people repeatedly re-enter the system at more costly intervention points, such as prisons or emergency units.

These authors also identify the lack of a sustainable long-term approach with cross-party support:

Governments come and go and have different priorities and methods of addressing them. A systems approach to reduce experiences of IPV and CAN in New Zealand is a long-term project and cross-party support over time would be a challenge to achieve and maintain but will be a necessary part of forward progress. (Carne et al., 2019, p. 27.)

5.1.3 The need for strategic systems analysis to inform continuous improvement

A related challenge is the need for a strategy of continuous improvement that measures system effectiveness using systems thinking tools and an overarching research and evaluation programme to inform system and service development. How outputs and outcomes for families and whānau are recorded and analysed also needs attention. As noted in Chapter 2, the lack of this results in duplications and gaps in knowledge. There is also a lack of transparency about the extent to which government agencies consider research and evaluation findings and recommendations, and act on them.

Many of the studies reviewed – and referenced in the annotated bibliography – include quantitative and qualitative evidence, including the voices of services users, families, whānau, kaimahi and other frontline workers and managers from community organisations and government agencies. They share their stories, experiences and insights, with the intention of informing change and improvements throughout the system. However, lack of co-ordination and sharing of research inhibits the way this research can inform system change.

5.2 Role of the government in enabling transformative systems change

5.2.1 Concept of stewardship

The concept of stewardship is used to frame the role of the Joint Venture for Family Violence and Sexual Violence in bringing together government agencies to collectively address the issue of family violence and sexual violence. The rationale for the joint venture interagency model relates to concerns about the commitment and engagement of other agencies over time. Joint accountability and collective ownership by agencies are intended to offset the competing demands of agencies’ core business with cross-agency work. The functions of the joint venture are outlined in the Cabinet Paper Breaking the intergenerational cycle of family violence and sexual violence (2018) as:

17.1 The mandate to lead a whole-of-government work programme to reduce family violence and sexual violence.

17.2 Authority to provide strategic policy and funding advice on behalf of all agencies involved in the response to family violence and sexual violence, including collective Budget advice.

17.3 Levers for Ministers collectively to prioritise the allocation of funding across different agencies to ensure effective delivery of a whole-of-government strategy and response.

17.4 Strategic leadership of the approach to commissioning family violence and sexual violence services, working alongside contracting agencies to reflect this in their funding strategies, including the development of new models of contracting.

17.5 An enduring, sustained commitment to reduce family violence and sexual violence that binds all of the agencies involved.

17.6 Accountability to the public and to Parliament for the performance of this whole-of government response – to substantially reduce family violence and sexual violence. (Cabinet paper 2018)50

Carne and colleagues identify effective stewardship as a fundamental factor in the success of a systems thinking approach that ‘requires leaders to lift their heads above the concerns and priorities of their own organisation to take on a shared responsibility for the bigger issues that cannot be solved by any single organisation’ (Carne et al., 2019, p. 26).

The Productivity Commission’s report (2015, p. 127) on effective social services discusses the government’s role in stewardship of the social services system. It recommended that the government take responsibility for system stewardship because of its unique regulatory and statutory powers, because it is a major funder of social services and in the interests of expediency. The Commission’s report recognised submissions that proposed joint stewardship with communities for social services but considered ‘such arrangements could distract and delay government from fulfilling responsibilities that are firmly its own’ (2015, p. 126). Rather, the Productivity Commission position was that partnering with other sectors of society is required to effectively implement these responsibilities and provides examples of devolution. It recommended that the government’s responsibility for system stewardship include:

- Conscious oversight of the system as a whole

- Clearly defining desired outcomes

- Monitoring overall system performance

- Prompting change when the system under-performs

- Identifying barriers to and opportunities for beneficial change, and leading the wider conversations required to achieve that change

- Setting standards and regulations

- Ensuring that data is collected, shared and used in ways that enhance system performance

- Improving capability

- Promoting an effective learning system

- Active management of the system architecture and enabling environment. (Productivity Commission, 2015, p. 127.)

Although the Productivity Commission’s report (2015) recommended against joint stewardship in favour of the government getting on with fulfilling its responsibilities, the question of power sharing between the government, iwi and communities in relation to decision-making about social services is an important ongoing debate.

5.2.2 Conditions for enabling system change

The government’s role in facilitating an enabling environment for system change has been examined in several reports. The Family Violence Death Review Committee’s fifth report (2016) recommended that directions for system integration were:

- Legislation frame – integrative practice principles in legislation;

- Investment that sustains family violence expertise and strengthens opportunities for intervention with those perpetrating family violence;

- Infrastructure – develop the workforce infrastructure for an integrated response system; and

- Organisational responsiveness – strengthen organisational responsiveness to family violence throughout the family violence system.

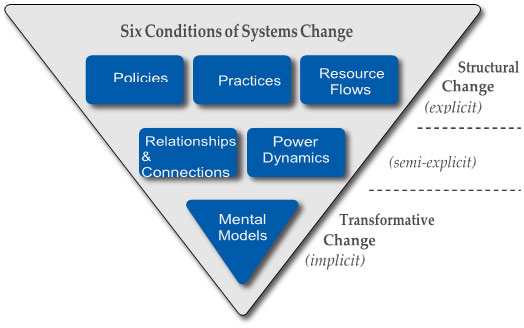

Carne et al. (2019, p. 17) set out the conditions for systems change based on the model by Kania, Kramer & Senge (2018): The Water of Systems Change, FSG.

| Systems change conditions — Definitions |

|---|

| Policies: Government, institutional and organizational rules, regulations, and priorities that guide the entity’s own and others’ actions. Practices: Espoused activities of institutions, coalitions, networks, and other entities targeted to improving social and environmental progress. Also, within the entity, the procedures, guidelines, or informal shared habits that comprise their work. Resource Flows: How money, people, knowledge, information, and other assets such as infrastructure are allocated and distributed. Relationships & Connections: Quality of connections and communication occurring among actors in the system, especially among those with differing histories and viewpoints. Power Dynamics: The distribution of decision-making power, authority, and both formal and informal influence among individuals and organizations. Mental Models: Habits of thought—deeply held beliefs and assumptions and taken-for-granted ways of operating that influence how we think, what we do, and how we talk. |

The level of ‘mental models’ is identified as the least visible but the most transformative condition for social change. This is because other conditions are not likely to shift without shifting these deeply held beliefs. In the case of family violence, sexual violence and child abuse, this relates to changing attitudes and beliefs about the ‘normalising narratives’ identified earlier in this report, such as negative gender constructs and we also add how children are viewed and listened to (Carne et al 2019, p 18).

5.3 Proposed models to transform the family violence system

There have been a number of proposals put forward to transform the family violence system over the last decade based on considerable work and consultation including:

The Glenn Inquiry, 2014

To transform the family violence and child abuse system, the Glenn Inquiry proposed an integrative, sustainable model working at multiple levels. This is the viable systems model (VSM), where viability:

… means that the necessary functions in the system work together coherently, and that the system is seen by key stakeholders as relevant, credible and legitimate.

We model a transformed system drawing on Beer’s Viable System Model which sets out five critical functions needed to work together to sustain a system:

- Operational effectiveness

- Coordination

- Tasking, resourcing, monitoring performance

- Scanning and planning

- Purpose and guidance

In relation to FV and CAN, each of these five functions will need to be present at multiple levels: national, regional and local; and will need effective communication between these levels. (Foote, Taylor, Nicholas, Carswell Wood, & Winstanley, 2014.)

The Way Forward – Backbone Collective 2014 and 2018

The Way Forward Model (Herbert & MacKenzie, 2014) also calls for an integrated systems approach to address IPV and child abuse. Herbert & MacKenzie’s paper in 2018 calls for:

… a national collaborative backbone agency – at arm’s length from central government – to be established as part of the infrastructure required to support the new integrated, whole-of-government approach to family violence and sexual violence …. We believe that the primary (but not necessarily the sole) purpose of the collaborative backbone agency would be to provide the glue to hold the integrated system together, to enable all key stakeholder groups to have collective ownership, accountability and responsibility for ensuring the system continually learns and improves over time. (Herbert & MacKenzie, 2018a)

Breaking the inter-generational cycle of family violence and sexual violence (Cabinet paper, 2018)

The proposed response system outlined in the Cabinet paper Breaking the inter-generational cycle of family violence and sexual violence (2018) proposes a strong integrated response throughout the government whereby each agency knows the role it should play in responding to and reducing violence and is equipped with the skills and resources it needs to fulfil its role. An integrated response (as informed by experts, victims and the sector) would:

16.1 significantly increase primary prevention, at the community and national level, so we build a culture of non-violence and change attitudes and behaviours that enable violence to occur and constrain help-seeking;

16.2 harness opportunities for early intervention by funding early intervention services that mitigate the impacts of trauma on children, youth and their families to prevent lifetime and intergenerational consequences;

16.3 help victims, children and families to get the help they need by ensuring that all relevant government and non-government organisations understand the dynamics and impacts of family and sexual violence, and know how to refer individual and families to the appropriate support;

16.4 ensure the immediate safety of victims through rapid multi-agency safety responses building on current innovations and learning from pilots such as the Integrated Safety Response (ISR) and Place Based Initiatives;

16.5 ensure specialist services are sustainably funded, better contracted, and support new approaches to service delivery at the community level so services better meet the complex needs of families and whānau, in particular those suffering intersecting forms of disadvantage or unique needs (such as the elderly and those with a disability); and

16.6 build awareness of effective interventions and ensuring that evaluation informs our priorities, and that communities, in particular Māori and Pacific communities, are supported and empowered to act on evaluation findings.

5.4 Government initiatives to facilitate the family violence system’s change

The recognition that the complexity of family violence, sexual violence and child abuse requires a multi-faceted and collaborative approach has resulted in the establishment of a number of government bodies since 1976. These are chronologically listed in table 6 (Carne et al., 2019, p. 32).

Table 6: National level government and community collaborative structures to address family violence from 1976 to 2020 (Carne et al., 2019, p. 32)

| Body | Year established |

|---|---|

| Joint Venture, Family Violence and Sexual Violence (including Joint Venture Business Unit) | 2018 |

| Multi Agency Team (MAT) | 2017 |

| Ministerial Group on Family and Sexual Violence | 2014 |

| Taskforce for Action on Sexual Violence | 2007 |

| Taskforce for Action on Violence within Families | 2005 |

| Family Violence Ministerial Group | 2005 |

| Te Rito Advisory Group | 2002 |

| Family Violence Focus Group | 1999 |

| Family Violence Unit | 1996 (disbanded 1999, new Family Violence Unit established 2011) |

| Family Violence Advisory Committee | 1994 |

| Crime Prevention Unit | 1993 |

| Crime Prevention Action Group | 1992 |

| Victims Task Force | 1987 |

| Family Violence Prevention Coordinating Committee | 1985 |

| National Advisory Committee on the Prevention of Child Abuse | 1981 |

| New Zealand Committee for Children | 1979 |

| Inter-departmental committee on child abuse | 1976 |

There does not appear to be any substantive studies of these established bodies that evaluate what worked well for what purpose, to identify key enablers of effective government and community collaboration. The Cabinet paper Breaking the inter-generational cycle of family violence and sexual violence (2018) identifies the following issues, which officials based on a short desktop review in March 2018 and consultations with NGOs and other officials:

19 Successive governments have tried to develop better cross-agency approaches … but have struggled to make lasting and substantive change. Prior attempts have used voluntary coordination through inter-agency taskforces, expert advisory groups, cross-agency boards and ministerial groups, but none have achieved sustained integration and systemic issues remain (for example, there is no overall strategy and prevention remains chronically underfunded).

20 Independent research has found that these earlier attempts were ultimately ineffectual … related to the limits of voluntary coordination and cross-agency working. Drivers of this lack of progress include:

20.1 It is not in the interests of any agency to make the case for the significant level of investment needed for integrated primary prevention and early intervention efforts, because this is not within the primary mandate of any agency;

20.2 Accountability for working with families experiencing violence is fragmented across ten departments (in particular, different agencies work with children, victims and perpetrators). Each agency has its own primary focus, resulting in a lack of overall system stewardship, strategy and family or whānau centred responses;

20.3 Momentum is lost because family violence and sexual violence has not been the collective priority of the relevant agencies. Each agency faces strong competing demands on their time and budgets, with family and sexual violence initiatives, (particularly those that cross agency and service delivery lines) often not resourced >sufficiently;

20.4 As with other wicked problems, policy changes in one area can hinder improvements made in another and the wider system response. For example, changes to one agency’s funding criteria can impact the security of providers reliant on multiple funding streams; and

20.5 Government has not always listened to the expertise of the sector, communities, Māori and others, and already stretched services are often not compensated for their efforts when they are asked for input. Sector engagement is led by multiple departments on their areas of focus, rather than being coordinated and sequenced to achieve collective objectives. (Cabinet paper, 2018, p. 5.)

From the literature, the extent of collaboration and power sharing between the government, communities and iwi has varied over time and been skewed towards the government’s favour. New models are emerging and there is currently more focus on how genuine partnerships can be developed to address these complex issues of family violence, sexual violence and child maltreatment. Critical analysis of the varied national coordination and strategic forums that have arisen over the last 40 years could provide insight into operationalising genuine collaborative partnerships at national, regional, and local levels.

Crown collaboration with Māori – Te Rōpū partnership with the joint venture51

The Crown has partnered with Māori to form Te Rōpū partnership with the Joint Venture for Family Violence and Sexual Violence. The membership of the interim Te Rōpū was announced on 18 December 2018. The terms of reference for Te Rōpū outline the partnership arrangements with the Crown, Ministers and a dedicated agency (the joint venture) ‘to deliver these shared goals, underpinned by the Treaty of Waitangi and the Crown’s obligations to uphold mana motuhake’. The interim Te Rōpū will also contribute to the development of a more enduring set of arrangements to formalise this partnership to give effect to this partnership in the initial stages of the development of a national strategy and action plan.

The Cabinet paper states that:

The Government is committed to substantially reducing family violence, sexual violence and violence within whānau. There is overwhelming evidence that a sustained, integrated response is required to achieve this goal, and that new ways of working across government and with whānau Māori and communities are needed to deliver this integrated response. …

The role of Te Rōpū is to provide an enduring mechanism to:

- Establish a partnership between Māori and the Crown (and especially for wāhine Māori) to transform the whole-of-government response to family violence, sexual violence and violence within whānau.

- Facilitate Māori views on what and how the Crown needs to operate in order to be able to create the change Māori want to see for Māori and to work with the Crown to give effect to such change.

- Ensure Māori express their own views on what works for Māori and their right to determine their own development (reflecting mana motuhake and rangatiratanga).

- Monitor and report on the Crown’s performance. Te Rōpū will report directly to the [Lead Minister], and will be supported by an independent secretariat.52

5.5 Whānau Ora outcomes framework and collective impact

We conclude the review with information about the development and implementation of the Whānau Ora outcomes framework and collective impact model, initiatives and evaluations, to propvide inisghts for developing a family violence system. The Whānau Ora outcomes framework includes a shared outcomes framework, developed through extensive consultation, and the use of a collective impact approach to achieve large-scale social change.

Whānau Ora outcomes framework

Whānau Ora is a major contemporary indigenous health initiative in Aotearoa driven by Māori cultural values. Its core goal is to empower whānau and communities to support them within the community context rather than individuals within an institutional context. The initiative also partly developed in response to a recognition by the government that standard ways of delivering social and health services were not working and that outcomes, particularly for Māori whānau, were not improving (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2017).

The Whānau Ora outcomes framework provides a nationally validated, and shared, reporting structure for all Whānau Ora providers. Led by the Taskforce on Whānau-Centred Initiatives in 2009, the Framework was informed through a consultation process, with a panel of national and international experts, a review of relevant literature, contributions of the experiences of health and social service agencies, hui throughout the country and written submissions from individuals and organisations.

During the last five years, data about the framework has been collected and stored at the Whānau Ora commissioning agencies. For example, outcome data for the North Island whānau is held by Whānau Tahi,53 which provides a software platform for planning and collaboration, workflow, KPI reporting and datacollection. As well, Whānau Ora works, and has been shown to work, in a diverse range of social and health areas, including employment, education, housing, justice, chronic conditions, physical activity and disability.54 Thus, Whānau Tahi also provides a useful and rigorous data management platform for the inter-rating of outcome data from multiple providers and issue areas.

A 2015 report by the New Zealand Productivity Commission found that the Whānau Ora Kaiārahi (Navigator) approach was a key example of an integrated whānau-centred approach supporting seamless access to health and social services.55 An independent 2018 report for the Minister of Whānau Ora also found:

- That the Whānau Ora Commissioning Approach results in positive change for whānau;

- That it creates the conditions for that change to be sustainable;

- That it operates within, and meets the requirements of, a structured accountability system; and

- That it operates in a transparent manner.56

As well, the Whānau Ora commissioning agencies have produced several publicly available research and evaluation reports that show whānau achieving short-, medium- and long-term outcomes.57

Whānau Ora and collective impact

The collective impact (CI) model recognises that large-scale social change requires broad cross-sector coordination. It also explains how substantially greater progress could be made in alleviating many of society’s most serious and complex social and environmental problems if non-profits, governments, businesses, and the public were brought together around a common agenda to create collective impact (Kania, Kramer, & others, 2011).

In 2015, the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency (formerly known as Te Pou Matakana) commisisoned 13 CI initiatives throughout the North Island. According to the Stanford Social Innovation Review, CI initiatives must meet the following five criteria to be considered collective impact (Kania et al., 2011):

- Common Agenda: All participating organisations (government agencies, non-profits, community members, etc.) have a shared vision for social change that includes a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving the problem through agreed upon actions.

- Shared Measurement System: Agreement on the ways success will be measured and reported with a short list of key indicators across all participating organisations.

- Mutually Reinforcing Activities: Engagement of a diverse set of stakeholders, typically across sectors, coordinating a set of differentiated activities through a mutually reinforcing plan of action.

- Continuous Communication: Frequent communications over a long period of time among key players within and across organisations, to build trust and inform on-going learning and adaptation of strategy.

- Backbone Organisation: On-going support provided by an independent staff dedicated to the initiative.The backbone staff tends to play six roles to move the initiative forward: Guide Vision and Strategy; Support Aligned Activity; Establish Shared Measurement Practices; Build Public Will; Advance Policy; and Mobilise Funding.

The Whānau Ora outcomes framework provided the partners with a common agenda and shared measurement system. Each collective was also contracted by the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency based on outcomes rather than outputs, leaving each collective to decide how to manage, organise and utlise their partnerships, services and resources. Each collective, made up of serveral partners, was responsible for nominating a lead partner for the collective who was responsible for organising and establishing a backbone organisation. A toolkit was also developed by the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency outlining the CI approach and performance criteria that collectives could use to assess their progress.

An evaluation of two of the CI initiatives was conducted in 2019. Results from the evaluation showed that after three years of the initiative, whānau:

- were making informed choices about the support they required and who they accessed support from, and were leveraging the knowledge, skills and capabilities within their whānau and networks to advance their collective interests;

- had learnt new skills such as budgeting, maintaining homes and accessing materials for making home improvements;

- could model to other whānau members their ability to take personal responsibility for their own health and wellbeing;

- had improved their interpersonal skills;

- had developed nurturing environments that provided for their physical, emotional, spiritual and mental wellbeing, and were confident to address crises and challenges when they arose;

- could articulate and implement healthy living habits in the home that supported their success;

- were achieving the knowledge, skills sets and qualifications to pursue training and employment that provided them with financial security and career options;

- were benefiting from being part of a Māori community group and/or organisation and were also accessing cultural knowledge, engaging in knowledge creation and transferring that knowledge amongst themselves; and

- were trained and serving as public, community and cultural champions, advocates and leaders.

51: breaking-the-inter-generational-cycle-of-family-violence-and-sexual-violence.pdf (justice.govt.nz)

53: Whānau Tahi provides a software platform for planning and collaboration, workflow, KPI reporting and datacollection. More information about Whānau Tahi can be found on their website: https://www.whanautahi.com/.

54: Research and evaluation reports for the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency can be found at https://whanauora.nz/resources/research/. Research and evalaution reports for Te Pūtahitanga can be found at http://www.teputahitanga.org/reports-and-research.

55: New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2015). More effective social services – final report. Retrieved from Wellington: New Zealand Productivity Commission website: https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/8981330814/social-services-final-report.pdf.

56: Te Puni Kōkiri. (2018). Whanau Ora Review – Tipu Mātoro ki te Ao – Final Report to the Minister of Whānau Ora. Retrieved from https://www.tpk.govt.nz/docs/tpk-wo-review-2019.pdf.

57: Research and evaluation reports for the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency can be found at https://whanauora.nz/resources/research/. Research and evalaution reports for Te Pūtahitanga can be found at http://www.teputahitanga.org/reports-and-research.