Part 3: How we prepare our work programme

We carry out regular environmental scanning to identify and assess issues, risks, and opportunities affecting the public sector. This helps us to prepare a work programme that is responsive to current and emerging risks, that anticipates future risks, that supports our ability to engage in longer-term scrutiny of intractable issues, and that takes advantage of opportunities for us to influence improvements in public sector performance.

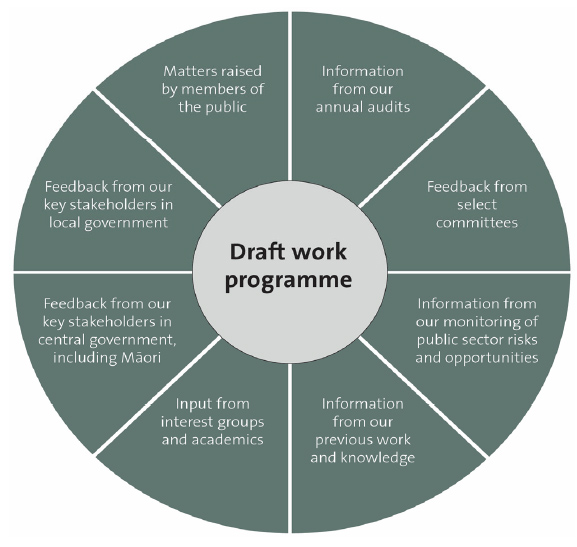

We draw on a range of sources to assess our environmental context and to help generate potential areas of interest. These sources include the information our auditors continually gather, our ongoing monitoring of risks, and our independent analysis of public sector performance and issues. We also draw on our previous work and knowledge – reports we have published (including inquiries, research reports, and the results of recent audits) and follow-up reports on how public organisations have implemented our recommendations.

Our central and local government advisory groups help us to better understand the common themes and issues in their respective sectors. Our discussions with select committees and the public organisations we audit are another source of information that we draw on.

Improving outcomes for Māori is an important consideration in planning our work programme. We work with public organisations such as the Office for Māori Crown Relations: Te Arawhiti and Te Puni Kōkiri to help us identify where we can best focus our work to influence the effectiveness of the public sector in improving outcomes for Māori.

Matters raised by members of the public and input from interest groups that we work with, such as Transparency International New Zealand, and academics also inform our planning.

The diagram shown here summarises the main sources of information we draw on to inform potential areas of interest in our draft work programme.

This year, we have assessed potential areas of interest and topics against the following criteria:

- materiality – the extent to which the topic or issue is significant and meaningful to New Zealanders and the extent to which it is common to or affects multiple public organisations;

- potential impact – the extent to which the work is likely to support or influence meaningful change or is likely to have impact beyond just one agency or group;

- the particular value we can add – the extent to which we can add value, given our knowledge and capabilities, unique view, and ability to influence;

- balance and coverage throughout the sector – ensuring that, over time, we are looking at a sufficiently wide range of public services and issues of relevance to New Zealand; and

- alignment to our strategy – potential contribution to advancing our strategic objectives.

Our operating environment

New Zealand's public sector is largely in good shape. Key indicators show that trust and confidence in the public sector remains high. New Zealand is seen as generally free of corruption and enjoys strong governance and accountability arrangements. Most New Zealanders have access to good quality public services which are, for the most part, reliable and well managed.

We operate in a challenging and changing environment. Changes in technology, our environment, and increasing social and cultural diversity mean the public's expectations of government are increasing. The COVID-19 pandemic creates new types of risks and issues which must be addressed.

Some of the main factors that will test our public services, and provide context for our work, are described below.

Several persistent and interconnected social issues are adversely affecting the lives of everyday New Zealanders and imposing significant costs on society

New Zealand’s high rates of family and sexual violence have significant economic, cultural, and social costs. Rates of violence are highest among some of our most vulnerable communities.

Family violence is widely recognised as a complex problem. It persists despite the efforts of successive governments, many government agencies, and the numerous community organisations working with those who are either harmed by or perpetrators of violence.

Harmful use of alcohol and drugs is a significant factor in criminal offending in our communities. About 60% of community-based offenders have an identified alcohol or drug problem, and 87% of prisoners have experienced an alcohol or drug problem during their lifetime.2 There are also strong links between those who struggle with addiction and those who struggle with mental health.

About one in five New Zealanders experience some form of mental illness or distress each year3. The social and economic costs are significant. The annual cost of serious mental illness, including addiction, is an estimated $12 billion each year.4 Suicide rates continue to increase, and our suicide rate for young people remains among the worst in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

About a quarter of New Zealand’s children currently live in poverty and are deprived of proper nutrition, a warm home, and the normal childhood experiences that others enjoy. The effects of poverty are far-reaching. Children who live in poverty have worse health and educational outcomes, and the economic costs of poverty are estimated to be in the range of $6-$8 billion per year.5

Although we remain above the OECD average, New Zealand’s levels of achievement in education are declining in some aspects. The latest Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report suggests that the main reasons for this include disproportionate rates of bullying, poor learning environments, truancy, deteriorating attitudes towards reading, and negative attitudes towards school.

By the time some young people get to secondary school leaving age, they do not have the general education, skills, or qualifications for direct entry into the workforce or to successfully engage in tertiary education.

In recent years, district health boards (DHBs) have been under increasing pressure to deliver services and results, and their financial results have deteriorated significantly. Demand for specialist health services and procedures continues to increase. Some New Zealanders experience inequities of access to health services, with a range of underlying socio-economic factors contributing to this.

Health spending is an increasingly significant factor in government financial sustainability, both in the short and longer term. It remains an ongoing challenge for DHBs to invest in health staff, services, infrastructure, and technology to meet New Zealand’s current and future healthcare needs, while ensuring their continued financial sustainability.

New Zealand’s housing and urban development system faces significant challenges with access to housing and its affordability. Several factors affect the supply of housing, but one of the most important is the supply of land and the planning rules for that.

Local government plays a particular role in this, including providing infrastructure, consenting, and construction. However, there has been some criticism directed at councils’ response to demand for housing, particularly in regions with significant population growth.6

New Zealanders most at risk of disadvantage are more severely affected by the lack of affordable housing. In the most extreme cases, this has resulted in people becoming homeless. People’s lack of a safe and secure place to live is also often coupled with their having other, multiple social needs that are also vital to their well-being. Problems associated with lower quality housing in New Zealand, including mould problems, have been linked to poor health outcomes (especially for children) and wider socio-economic outcomes.

There are also system-wide issues that the public sector needs to address

Māori continue to experience disparities of outcomes relative to other New Zealanders in housing, health, and education. In the “post-Treaty settlement” environment, the public sector faces widespread challenges in terms of resourcing and delivering on the Crown’s obligations and commitments made in Treaty settlement Acts.

Assuming that the Public Services Bill is passed into law, the public sector will also need to meet new requirements for organisations in the public service to strengthen capability to engage and work in partnership with Māori.

New Zealanders experience inequities in the delivery of services in the regions, and demand for services in our regional communities is expected to increase during the coming years – particularly in the northern region – in the face of a growing, ageing, and changing population.

Pressure on local infrastructure – roading, transport, drinking water, wastewater, and storm water – is also increasing. Replacing and upgrading critical infrastructure will be costly for ratepayers. Small and remote communities will face particular challenges with ageing infrastructure and declining populations.

These local authorities have a much smaller rate-payer base with which to fund these investments. The populations of many small and rural communities also have lower than average incomes and higher levels of social deprivation, which add to affordability problems.7 This could be further exacerbated by the consequences of Covid-19.

Climate change presents some particular challenges for our infrastructure. Local authorities will need to make some difficult decisions to determine how they will respond. Significant action is needed, but the path remains uncertain, and it is unclear who will bear the costs.

Against this backdrop, the public sector faces several significant pressures

New Zealand, like other parts of the world, is significantly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. Covid-19 will have an unprecedented effect on our economy, and the public sector will be managing this for many years to come.

The public is increasingly sensitive to the risks that the nation faces from significant health-related events, economic shocks, biosecurity threats, and natural hazards, as well as threats to our national security. The public sector will need to provide greater assurance to the public about what it is doing to prepare for, and respond to, these types of risks.

As the Government develops its strategy to stimulate economic recovery, in part through significant investment in infrastructure projects, sound financial management, governance, and accountability in public organisations is more important than ever.

Fraud and integrity risks increase when significant new money enters the system and there are expectations of fast and pressured delivery. There is increasing pressure on the public sector to maintain expected standards of integrity. Although New Zealand’s public sector is perceived as one of the least corrupt in the world – consistently ranked among the top two in the Transparency International Corruptions Perceptions Index – we cannot be complacent.

Internationally, and here in New Zealand, people’s expectations about their involvement in decisions that affect their lives, the value they receive from their public services, and the information about how public funds are spent are at risk of exceeding the ability of the public sector to deliver. This will affect trust and confidence in the public sector – in particular, that of some minority populations.8 The uncertain operating environment will only exacerbate this.

The public sector is grappling with how to respond. Significant reforms in many parts of the public sector, such as in health and education, are proposed or are under way. As the public sector attempts to work across agency boundaries to tackle some of the more complex problems facing society, it is exploring new organisational forms and models of governance – such as joint ventures.

There are significant expectations on the public sector to support co-ordinated action to deliver on the Government’s well-being aspirations and to ensure that New Zealand meets its international obligations for the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

All of this provides context for our proposed work programme as set out in this draft annual plan

When considering where to focus our work, we must continue to prioritise. For this draft annual plan, we have tried to balance an increased emphasis on examining issues in the social sector (given the Government’s significant investment in, and focus on, well-being) with work that examines the fundamentals of good organisational and financial management and governance, and the need to continue to influence the shape and direction of public sector reform. We provide more information about how we identify topics for our work programme at the beginning of Part 3.

2: He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (December 2018), available at mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz.

3: He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (December 2018), available at mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz.

4 He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (December 2018), available at mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz.

5: Children’s Commissioner’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty (December 2012), Solutions to Child Poverty in New Zealand: Evidence for Action, available at www.occ.org.nz.

6: Productivity Commission (19 February 2020), Insights into Local Government, available at www.productivity.govt.nz.

7: Productivity Commission (19 February 2020), Insights into Local Government, available at www.productivity.govt.nz.

8: Kiwis Count data breakdown is available on the State Services Commission’s website at ssc.govt.nz.