Medium-term financial stability of universities

Financial sustainability

3.1

In our 2017 report on the TEI audit results, we prioritised ITPs because of the sharp decrease in their financial sustainability since 2016. We concluded that universities were in a stronger position, but this year we looked at their results in more detail. We were interested in understanding whether the operating environment that had led to difficulties in ITPs was likely to have a similar effect on the performance of universities.

3.2

Most universities have continued to increase their revenue, surpluses, assets, and equity. All universities have positive net cash flows from operations.

3.3

Universities have low levels of debt. Auckland University of Technology (AUT) (15%) and Victoria University of Wellington (VUW) (9%) have the highest debt-to-asset ratio, but all of the others have negligible debt (1% or less).

3.4

Universities are also spending more on capital expenditure than the amount their assets are depreciating by. In most cases, this should mean that universities are improving the assets available for teaching, learning, and research.

3.5

Universities have also been managing within their means. Total revenue increased by 14.1% and costs by 13.3% since 2015. The universities are engaged in numerous benchmarking groups and collaborative projects to help them understand and manage their costs.

3.6

We looked at data on staffing-to-student ratios to see whether universities were managing costs by reducing staff. Overall, the ratio of academic staff to EFTS slightly worsened from 2007 to 2018 – from 16.1 students per staff member to 16.5 students per staff member. However, the ratio of all staff to students went up in all but one university.

3.7

VUW, AUT, and the University of Otago’s costs ran marginally ahead of revenue in total during 2015-18 (1.9%, 0.8%, and 1.5% respectively), but all have good net cash flow. This indicates some spending to reduce costs in future years.

3.8

Massey is the only university to have had a downturn in revenue in 2018. However, it increased its net cash flow from operations, and its equity increased by $13 million.

3.9

Lincoln University returned to a more stable financial position in 2018, mostly because it received the proceeds of an earthquake-related insurance claim. However, Lincoln’s small size, its mix of education programmes, and the condition of its physical campus present significant challenges. It still needs to invest heavily in its facilities to attract students.

3.10

On 23 November, the Government approved $80 million to help Lincoln University rebuild its earthquake-damaged science facilities. The investment will take place alongside a modernisation programme covering teaching, research, and partnerships with other agencies.

3.11

The financial performance of universities is intrinsically linked to the volume of students they attract. Although most universities have other revenue streams (such as subsidiary companies, research, and charitable giving), the revenue stream from students (including government funding for domestic students) dominates their income.

Student enrolments

3.12

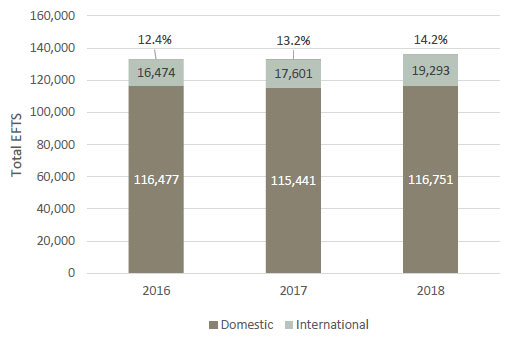

We looked at the change in enrolments from 2016 to 2018, and in some cases compared the 2018 enrolments to 2007. We chose 2007 because this was the year after some colleges were merged into universities. It was also the year before the global financial crisis. A weakened economy is one factor that can have a positive effect on enrolment into tertiary education. We were also interested to see whether the universities’ reliance on revenue from overseas students was increasing. Figure 5 shows the total enrolments expressed in EFTS for 2016 to 2018.

Domestic student enrolments

3.13

For all universities, domestic enrolments increased by 1.14% compared to 2017, are slightly higher than in 2016, and are 2% higher than in 2007. Only Massey University and Lincoln University had fewer enrolments compared to 2017 and 2016.

3.14

Universities have a much more stable flow of domestic students than other types of tertiary provider. Three out of four school-leavers entering tertiary education with a qualification at level 3 choose to go to university. This proportion is not changing much over time, although the number of school- leavers not entering further education straight after leaving school increased sharply between 2017 and 2018. However, the number of school-leavers is expected to start rising again by 2021, from about 60,000 a year to about 65,000 a year.

Figure 5

Equivalent full-time student enrolments (EFTS) at universities, 2016 to 2018, including the percentage of international students

Source: University annual reports.

International student enrolments

3.15

International EFTS enrolments were up 9.61% from 2017 (up 15% since 2007). The proportion of international students has increased to 14.2% from 13.2% last year and 12.4% in 2016.

3.16

However, for most universities, the proportion of revenue from international students and the proportion of revenue from domestic students was about the same in 2018 as it was in 2007. This is partly because the number of international students is much lower than the number of domestic students and partly because universities are increasing their revenue from other sources.

3.17

The Universities of Canterbury, Otago, and Waikato, and VUW have little international EFTS growth as a percentage of the total student population compared with 2007. However, demand at the University of Canterbury will have been affected by the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes, and there are signs that demand has started to increase.

3.18

Conversely, the University of Auckland has experienced significant growth in demand from international students since 2007 (up 64%), and international students now make up 15% of its total enrolments. Massey University’s international EFTS are now 18% of total EFTS, compared to 14% in 2007.

3.19

Lincoln University has the highest exposure to international student markets (38% of total students are international students), compared to 32% in 2007.

3.20

We have become aware of an increasing trend of international students enrolling in courses in New Zealand at level 8 and higher on the qualifications framework (such as taught Masters’ degrees). These courses are usually of less than a year’s duration after allowing for prior learning.

3.21

We cannot tell whether the trend is significant enough to contribute to an overdependence on revenue from some international markets. We suggest that the Committee ask the TEC about these trends, as it collects more information than is contained in the annual reports.

Conclusion

3.22

Universities are in good financial standing, with low debt and strong equity. Although future international student enrolment patterns might be more volatile than in the past, universities should have enough resources to manage any period of adjustment.

3.23

Several other operating environment factors might have a bearing on the future success of universities.

3.24

For example, government revenue for level 3 and above domestic student tuition increased by 1.6% from 2019, with a further 1.8% from 2020. Although some costs are rising more quickly than this, universities appear to be managing cost pressures.

3.25

The numbers of domestic students should also start to rise again in 2021. If historical patterns prevail, then universities should see further increases in domestic student enrolments.

3.26

We are aware that universities are concerned about how their position on various international ranking assessments might affect their ability to attract academic staff and international students. Some universities see this as their major strategic risk, and this is something the Committee could be interested in exploring further with Universities New Zealand, Education New Zealand, and the TEC.