Part 5: Better management of stormwater systems is needed

5.1

In this Part, we discuss the three councils':

- improvements in their asset management planning and practices;

- maintenance of their current stormwater systems;

- need to improve their information to help them prioritise funding for their most important assets;

- need to improve the delivery of planned capital spending; and

- need to work effectively with others.

Councils are improving their asset management planning and practices, with further improvement needed

5.2

The three councils are in the process of improving their asset management planning. These improvements should lead to the three councils managing their stormwater systems better. However, they need to do more, such as addressing weaknesses identified in their asset information.

5.3

Asset management planning helps organisations manage their assets effectively to support the delivery of services. We expected the three councils to have effective asset management planning to ensure that their stormwater system continues to deliver the agreed levels of service now and in the future.

5.4

Thames-Coromandel District Council has improved its asset management practices, including by introducing new asset management software that it expects will provide consistent and sustainable management of all of its assets. It has also put in place a council-wide asset management policy.

5.5

The Council is planning to improve its asset management practices further, including by:

- strengthening the connection between the infrastructure strategy and asset management plans;

- basing renewal planning on the condition of the assets; and

- completing an asset management maturity review of the three waters activities.

5.6

Wellington Water is integrating and improving asset management approaches developed by its shareholding councils. Wellington Water is also working to align asset management planning and investment decisions throughout the Wellington region with:

- a strategic asset management plan;

- regional service plans; and

- a regionally based framework for prioritising projects (also called the smart investment approach).

5.7

Porirua City Council and Wellington Water staff told us that they consider that this new smart investment approach means that investment in the stormwater system is more evidence-based, more strategic, and proactive rather than reactive.

5.8

An internal audit of Dunedin City Council's three waters asset management planning, completed in December 2017, found that there was:

- a lack of overarching asset management plans;

- a lack of a structured approach to asset maintenance planning;

- poor quality of asset plant data; and

- a lack of integration between asset management systems.

5.9

Dunedin City Council told us that it is addressing these issues through an asset management improvement programme.

5.10

These improvements by the three councils should lead to better management of stormwater systems. However, they need to do more, including improving asset information. We encourage the three councils and Wellington Water to continue improving their asset management planning practices.

Councils need to effectively maintain their stormwater systems

5.11

Councils need to effectively maintain their stormwater systems to ensure that they operate at design capacity during rainfall. If the maintenance of the stormwater system is outsourced, this needs to be supported by effective contract management, including through setting appropriate performance measures. Councils need to monitor and manage a contractor's performance so they can assess whether they are receiving what was contracted.

5.12

Thames-Coromandel District Council and Dunedin City Council outsource the maintenance of their stormwater systems to external contractors. Wellington Water has a contract with Porirua City Council's Works Operations Unit to maintain Porirua's stormwater system. These contractors are responsible for planned and unplanned maintenance, such as responding to people's complaints.

5.13

The three councils have a schedule of planned maintenance for their stormwater systems. For example, contractors inspect and clear critical inlets in Porirua monthly. The three councils and Wellington Water ensure that the work is done to the required standard through spot checks and audits.

5.14

The three councils also carry out maintenance of their stormwater systems before a predicted extreme rainfall event, such as checking that inlets into the stormwater infrastructure is clear. This helps ensure that the stormwater systems can disperse rainfall without blockages.

5.15

A lack of maintenance caused some of the flooding in South Dunedin in 2015 because blockages in the stormwater system meant that water was not being dispersed as fast as it could have been. Since 2015, Dunedin City Council has improved the maintenance of its stormwater system by amending contracts with higher service standards when they have been renewed, better monitoring of contracts, and spending more on maintenance.

5.16

Staff from Porirua City Council, Wellington Water, and Thames-Coromandel District Council did not raise any issues about the maintenance of their systems. However, there are some matters for improvement. For example:

- an internal audit found that Dunedin City Council does not have a structured approach to planning asset maintenance; and

- Thames-Coromandel District Council could make more use of maintenance information in renewals planning.

Better information would help councils prioritise funding for their most important assets

5.17

The three councils have increased their planned capital spending for stormwater infrastructure compared with previous forecasts. We cannot provide assurance about whether this spending is focused in the right areas because of the weaknesses in the three councils' information about their flood risk.

5.18

Addressing the identified weaknesses in information and the current state of their stormwater systems would help the three councils to better identify and prioritise the work needed to achieve the agreed levels of service, and the cost of doing so.

5.19

We compared the three councils' planned capital spending for stormwater infrastructure for 2019-25 in their 2018-28 long-term plans with what they forecast in their 2015-25 long-term plans.

5.20

Porirua City Council has increased its planned capital spending by 131%, Thames-Coromandel District Council by 72%, and Dunedin City Council by 31%. The increases are mainly for renewing their stormwater infrastructure and increasing levels of service.

5.21

The three councils are not alone in increasing their planned capital spending on stormwater infrastructure. Figure 4 shows that, generally, councils have increased their planned capital spending. The national average increase is by 59%. This consists of a:

- 98% increase in planned capital spending to increase the levels of service;

- 45% increase for renewing stormwater infrastructure; and

- 32% increase to cater for growth.

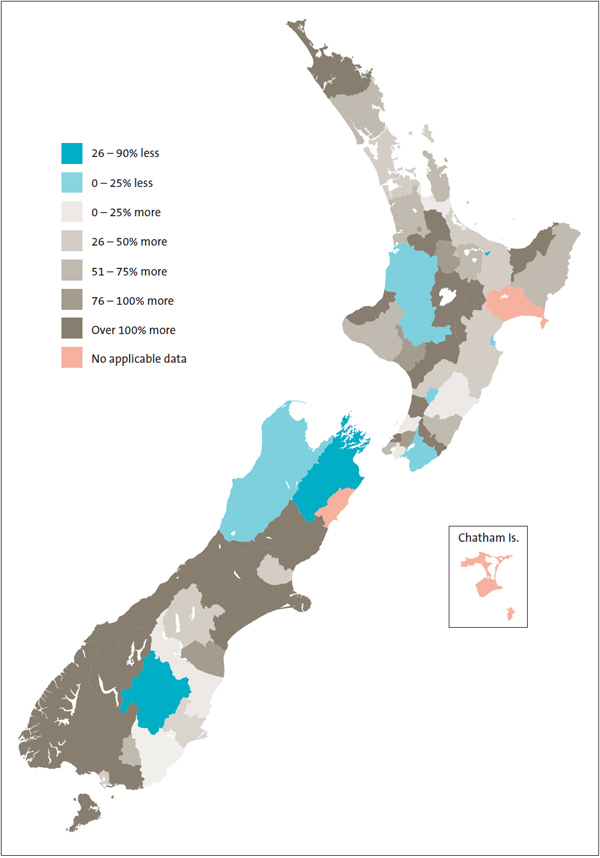

Figure 4

Changes in councils' planned capital spending on stormwater infrastructure for 2019-25 in their 2018-28 long-term plans, compared with their 2015-25 long-term plans

Most, but not all, councils are planning to spend more on capital.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

5.22

In previous years, we have outlined our concern that some councils are not adequately reinvesting in their assets to maintain current levels of service.12 If nothing changes, the under-investment will increase the risk of the stormwater system being unable to cope with heavy rainfall, resulting in people's properties being flooded.

5.23

Our concerns are based on the gap between the depreciation of stormwater assets and what councils were spending on the renewal of those assets. This gap indicates that the assets are likely to be wearing out faster than they are being renewed.

5.24

To understand how councils are planning to reinvest in their stormwater assets, we compared planned renewal and replacement capital spending with depreciation for 2019-28. Most councils (46 out of 67) are planning to spend less than 60% of depreciation on renewing and replacing stormwater assets from 2019 to 2028.

5.25

Figure 5 shows the forecast renewal and replacement capital expenditure compared with depreciation for 2019 to 2028. The national average for the period from 2019 to 2028 is 52%. This is the equivalent of wearing out stormwater assets twice as fast as they are being replaced.

Figure 5

Forecast renewal and replacement capital expenditure compared with depreciation for stormwater assets, 2018/19 to 2027/28

The bars would be close to 100% if assets were replaced at the same rate as they were used up.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

5.26

For the councils we looked at:

- Porirua City Council is not planning for any spending on renewing stormwater assets.

- Dunedin City Council is planning to spend 115% of depreciation on renewing and replacing stormwater assets.

- Thames-Coromandel District Council is planning to spend 89% of depreciation.

5.27

However, these figures do not tell the whole story. For example, Porirua City Council is planning to spend more than $15 million during 2019-28 to increase the levels of service its stormwater system provides. This will include some renewing of stormwater infrastructure that is not recognised in the figures above since the main reason for doing the work is to increase the capacity of the stormwater system rather than renewing it. Porirua City Council does not expect to carry out major renewals until the 2030s because that is when the Council expects its stormwater infrastructure to start reaching the end of its useful life.

5.28

This is in contrast with Dunedin City Council. The Council is catching up on a backlog of assets that need replacing because they are past their useful lives. It has also had issues in delivering its planned capital spending, which has meant that this backlog has increased over time (see paragraphs 5.31-5.40 for more information).

5.29

Addressing the identified weaknesses in information about their flood risk and the current state of their stormwater systems would help the three councils to better identify and prioritise the work needed to achieve the agreed levels of service and the cost of doing so. It would also allow the Council to give people confidence that the stormwater system will continue to protect their homes from flooding.

5.30

For example, the three councils primarily based their renewals planning on the age of their assets. However, if they had better information about the condition and performance of their assets, the councils would have more certainty about when these needed to be replaced.

Councils need to improve their delivery of planned capital spending

5.31

Some councils have had issues in delivering their planned capital work programmes. Better information would help councils prioritise funding. However, there is still a risk that, if councils continue to under-deliver their planned capital spending programme for stormwater infrastructure, their stormwater systems will not deliver the agreed levels of service in the future. This could lead to more flooding.

5.32

The three councils are making changes to improve their delivery of their capital spending programmes.

Figure 6

Councils' actual capital spending on stormwater infrastructure compared with planned spending, 2014/15 to 2016/17

Many councils in the North Island spent less than half of what they had planned for.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General, based on figures in councils' 2015-25 long-term plans.

5.33

Figure 6 shows that, from 2014/15 to 2016/17, 33 of 67 councils spent less than 80% of their overall planned capital expenditure for stormwater infrastructure. Only two councils consistently spent 80%-120% of their planned capital expenditure each year.

5.34

Between 2014/15 and 2016/17, Dunedin City Council spent 87% of planned capital expenditure, Porirua City Council spent 141%, and Thames-Coromandel District Council spent 36%. However, Figure 7 shows that there were significant variances in the three councils' actual spending on stormwater infrastructure compared with planned spending during those three years.

Figure 7

Actual capital spending on stormwater infrastructure as a percentage of planned spending, by council, 2014/15 to 2016/17

For the last three years, none of the three councils consistently spent close to what they had planned.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General, based on figures in the three councils' 2015-25 long-term plans.

5.35

Some of the reasons for the three council's under- and overspending include:

- delays in projects;

- unspent money from projects completed under-budget being added to next year's budget;

- over-budgeting and changes in scope;

- internal capacity and capability;

- procurement processes;

- contaminated ground; and

- the availability of contractors.

5.36

These reasons are similar to what we reported in our 2018 report, Managing the supply of and demand for drinking water.

5.37

The three councils are making changes to improve their delivery of their capital programmes. For example, Dunedin City Council is setting up an engineering support consultancy panel, and Thames-Coromandel District Council has created a new team to manage the delivery of capital projects.

5.38

The situation of historically underspending planned capital expenditure while planning to significantly increase capital expenditure on stormwater infrastructure is not unique to the three councils.

5.39

We identified 20 councils that increased their planned capital expenditure by more than 10% in 2019-25 compared to previous forecasts but spent less than 80% of their planned capital expenditure from 2014/15 to 2016/17.

5.40

In our view, if councils are going to deliver the planned increase in capital expenditure on stormwater infrastructure, they will need to make improvements, including improving their information to plan better (see Recommendations 1 and 4) and increasing internal capacity and capability (see Recommendation 5). Otherwise, there is a risk that the stormwater system will not deliver the agreed levels of service in the future.

Councils need to work effectively with others

5.41

Regional, city, and district councils' roles and responsibilities for hazard management, including flooding, are interconnected (see paragraphs 1.3-1.6).

5.42

For example, Dunedin City Council's stormwater piped network discharges into the Taieri River and tributaries, for which the Otago Regional Council manages the flood protection. When the Taieri River and tributaries are high, stormwater discharge is hindered, leading to backflow and flooding in Mosgiel.

5.43

We expect city and district councils to work effectively with regional councils to manage flood risk in their areas.

5.44

We observed in each of the three councils that greater clarity about roles and responsibilities would support more effective management of flood risks. This includes co-ordinating work programmes, sharing hazard information, and being clear about who is responsible for maintaining what.

5.45

Waikato Regional Council is leading work to understand some flood risks in the Thames-Coromandel district and to share hazard information in the Waikato region. Staff from Thames-Coromandel District Council and Waikato Regional Council told us that they had a good relationship but that roles and responsibilities between the councils could be clearer – for example, responsibility for managing coastal hazards.

5.46

Councils also need to manage the different parts of their stormwater systems holistically. This can be challenging because separate departments within a city or district council, the regional council, or private landowners can manage different parts of the system (see Figure 8).

5.47

For example, Dunedin City Council has little information on watercourses and private drains. Responsibility for these are split between the Council, Otago Regional Council, and private landowners. This means that there is a lack of clarity about who is responsible for watercourses. There are also concerns that a lack of renewals and maintenance for watercourses and private drains will increase the risk of flooding.

Figure 8

Illustration of the different roles and responsibilities for the stormwater system

Different parts of the stormwater system are managed by different agencies or individuals.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

5.48

In our view, there is also an opportunity for all councils to work together in new ways to address shared challenges in managing their stormwater systems, such as collaborating to improve their capability in asset management and in responding to climate change. During our audit, we saw two examples of councils collaborating in this way.

5.49

Wellington Water's predecessor, Capacity Infrastructure Services, took over management of Porirua City Council's stormwater system in 2013. Porirua City Council observed that Wellington Water raised technical, operating, and management capabilities in the Wellington region. This observation was supported by staff from the Council and Greater Wellington Regional Council, who told us that Wellington Water has improved the management of Porirua City Council's stormwater system.

5.50

A report commissioned by the Local Government Commission in 2016 reported that the Wellington Water model was showing signs of providing a more efficient and effective service than previous arrangements. It also noted that the model was still maturing.

5.51

Thames-Coromandel District Council and eight other Waikato councils have recently agreed to prepare a business case to set up a centre of excellence under a Water Asset Technical Accord to support the councils to improve the management of their water assets.

5.52

The new Water Asset Technical Accord is aiming to establish best practice in water and wastewater management and provide the councils with guidance on asset and environmental management, compliance frameworks, and investment decision-making. This builds on the region's Road Asset Technical Accord.

5.53

In our view, there is an opportunity for councils to collaborate more to address their shared challenges.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that councils identify and use opportunities to work together with relevant organisations to more effectively manage their stormwater systems. |

5.54

Councils might need help from organisations that have an interest in the local government sector, such as the Department of Internal Affairs, the Ministry for the Environment, and Local Government New Zealand, to facilitate this.

5.55

Some councils noted that this could include central government providing greater direction to councils. Current central government guidance includes these guides issued by the Ministry for the Environment:

- Climate change effects and impacts assessment: A guidance manual for local government in New Zealand, May 2008;

- Climate Change Projections for New Zealand, September 2018;

- Coastal Hazards and Climate Change: Guidance for Local Government, December 2017; and

- Preparing for future flooding: A guide for local government in New Zealand, May 2010.

5.56

There is also a voluntary New Zealand Standard Managing Flood Risk – A Process Standard, published in 2008. However, there is currently no mandatory national standard for managing flood risk or natural hazards. A national policy statement for natural hazards is currently proposed.

5.57

During our audit, the Government announced the Three Waters Review. This review is looking at how to improve the management of New Zealand's drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater. The review is looking at the options for improving the management of the three waters, including the service delivery, funding, and regulatory arrangements.

| Questions to consider |

|---|

| For councils: |

| How do you know that your maintenance regimes are supporting you in achieving the intended level of service? |

| How are you prioritising and planning your work programme to ensure that the stormwater system is achieving, and will continue to achieve, the intended level of service? |

| Do you have the right people and skills to deliver your work programme? |

| For people to ask their councillor: |

How is the council working to address any issues in delivering the level of protection?

|

12: For example, Matters arising from the 2015-25 local authority long-term plans (December 2015), paragraphs 2.11-2.19; Local government: Results of the 2014/15 audits (April 2016), paragraphs 1.37-1.45; Local government: Results of the 2015/16 audits (April 2017), paragraphs 1.22-1.29; and Local government: Results of the 2016/17 audits (May 2018), paragraphs 1.14-1.19. These reports are available on our website, www.oag.govt.nz.