Part 3: Matters we identified from our audits

3.1

In this Part, we set out matters from the 2017 school audits that we consider important enough to bring to the Secretary for Education's attention.

School audit timeliness and improving the "audit pipeline"

3.2

We worked with the Ministry to improve the timeliness of the 2017 school audits. If the audits are not timely, the information presented is less relevant and proper accountability is difficult to achieve. Auditors received 2263 (93%) draft financial statements for audit by the statutory deadline of 31 March, an improvement on the previous year (87%).

3.3

Auditors plan and have resources available between February and May each year. Because of the number of schools, meeting the May deadline depends on auditors receiving draft financial statements throughout February and March. Instead, auditors received 1422 (58%) draft financial statements in the last two weeks of March, with 970 draft financial statements received in the last week.

3.4

Although most schools met the deadline for submitting their financial statements for audit, receiving most of the school draft financial statements for audit late in March reduces the time available to complete the audits. This puts pressure on schools, financial service providers, and auditors to complete final financial statements and sign the audit reports before the statutory deadline.

3.5

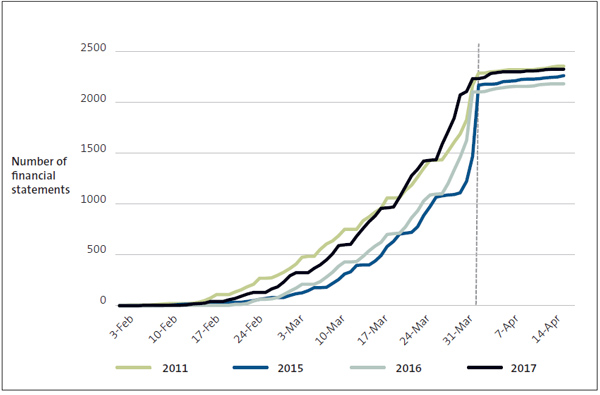

Before Novopay was introduced in 2012, requiring additional payroll reporting, auditors would get draft financial statements throughout February and March, which allowed them to spread their workloads better (see Figure 2). For the 2017 audits, we changed our approach to the payroll audit work. All payroll reports were sent out to schools at the same time and earlier than in previous years. As a result, some auditors received draft financial statements earlier, which helped improve the timeliness of reporting.

Figure 4

Date on which schools provided draft financial statements for audit

The line graph shows that in 2017 draft financial statements were received earlier than in 2015 and 2016, but still later than 2011, which was the last year we met our target of 95% of school audits completed by 31 May.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

3.6

We will take this approach for the audit work on the 2018 payroll information. We are also talking with the Ministry and the sector to find ways to make school audits go as smoothly as possible. The Ministry's appointment of a project manager to oversee school financial reporting for 2018 will help to ensure that schools and auditors have all the information they need to complete the audits in a timely manner.

3.7

We intend to use different communication channels (such as the New Zealand Trustees Association newsletter) where we are able to, to ensure that schools know their roles and responsibilities for financial reporting. We will also use these channels to reinforce what is expected of schools, so that we can complete their audits efficiently.

Quality of school financial statements

3.8

Overall, our auditors continue to see an improvement in the quality of the financial statements that they receive for audit. Updated and more timely guidance from the Ministry has helped this, as well as schools becoming more familiar with the Ministry's Kiwi Park model. The guidance for 2018 includes a checklist for schools that must report at Tier 1,3 to help them with the extra disclosures. In general, schools that prepare their own financial statements, or schools that use providers who prepare financial statements for only a few schools, are responsible for the poor-quality financial statements.

3.9

The Ministry's sector working group, attended by representatives from our Office and the school sector, has been valuable in improving the guidance available to schools. It is also good to see the Ministry repeating its Kiwi Park regional workshops this year to help schools and service providers use the model effectively. However, because most schools are now more familiar with the model, it might be more helpful in the future to provide financial reporting workshops. These workshops could focus on those matters of financial reporting that schools might struggle with.

3.10

In our report last year, we recommended that the Ministry provide further guidance and training to schools on preparing a statement of cash flows. We are still seeing an over-reliance on the worksheets in the Kiwi Park model without a clear understanding of what the cash flow statement should be showing. As a result, we have repeated our recommendation.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education provide further guidance and consider providing training to schools on preparing a statement of cash flows. |

School payroll reporting

3.11

One reason for the delay in schools providing financial statements for audit over the last few years has been the school payroll reporting. Because of the payroll error reports (overpayments, stop pays, and funding code errors) and leave liability reports for non-teaching staff, schools could not provide their financial statements to auditors early. This resulted in most schools providing financial statements for audit at the end of March (see Figure 4).

3.12

Because the occurrence of payroll errors in Novopay has reduced, many of the payroll errors reported to schools were not material. After some analysis of the 2016 payroll information, we agreed with the Ministry that schools would be sent the payroll error reports as at October 2017. If significant errors were found in the remaining months, these would be directly communicated to the affected schools. Using earlier information meant that the Ministry's appointed auditor could carry out the necessary audit work on these reports earlier. As a result, schools received all the payroll information they needed on 5 February 2018.

3.13

As part of its audit work on payroll, the Ministry's appointed auditor carries out data analytics on the payroll information. The Ministry first considers any exceptions from our expectations that we have identified. If the Ministry does not have the information available to resolve the exceptions, it sends them to schools and auditors to resolve. Auditors must resolve the exceptions before completing the school's audit.

3.14

For 2017, there were some delays in the Ministry's testing of the payroll exceptions. Our appointed auditor experienced initial delays with the data, and the Ministry then had challenges resourcing the work. Because of changes in personnel at the Ministry, there was also a lack of understanding about how much testing was needed. We had to take a staged approach to giving clearance to auditors to complete their audits, which caused significant disruption for some auditors. Auditors also did not receive enough information to resolve some of the exceptions.

3.15

The Ministry encouraged schools to complete their draft financial statements as soon as they received their payroll information. The early release of the payroll reporting helped to improve the flow of financial statements to auditors, although, as explained above, auditors still did not receive most of these until the end of March. However, the issues we had with the payroll exceptions created extra work for the school auditors and affected the ability of the auditors to complete all audits by 31 May.

3.16

For the 2018 audits, it is important that all parties work together to meet the agreed time frames. Having a project manager with oversight of the complete school financial reporting process should help to achieve this for the 2018 audits.

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education, for the 2018 audit of the school payroll: • make resources available to meet the agreed timetable, including enough time for the Ministry's internal quality assurance processes; • keep a record of actions agreed at payroll stakeholder meetings; and • continue to encourage schools to prepare draft financial statements when they receive the payroll information, and provide those draft financial statements to the auditor as soon as possible. |

School annual reports

3.17

In our report last year, we referred to the new requirement for schools to make their annual reports available on their websites and the difficulties that auditors had getting full copies of the Annual Report. The Education Act 1989 and the Ministry specifies a school must include in its Annual Report an analysis of variance, a list of trustees, financial statements (including the statement of responsibility), and a statement of Kiwisport funding.

3.18

Our auditors found that many schools were not aware of the requirement to publish their Annual Reports, even though the Ministry has provided guidance on this several times. Our auditors reminded schools of this requirement in their management letters to school boards.

3.19

Our auditors do not always receive a complete Annual Report for audit, which means they have to spend time asking for the different documents that make this up. We are aware that the Ministry does provide information on this in its Annual Reporting Circular, including a checklist, but there might need to be further communication about this matter.

3.20

It is not clear how many schools have met the requirement to put their Annual Report on their website. If it comes to our attention during the following year's audit that the school has not published its Annual Report, we will report it to the board. However, this does not promote timely accountability.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend the Ministry of Education reinforce its guidance to schools on preparing and publishing their annual report, and consider how it can confirm that schools are reporting to their communities by publishing their Annual Reports online, in a timely manner. |

Cyclical maintenance

3.21

Our auditors are still finding cyclical maintenance a challenging area to audit. Many schools do not understand the provision and do not have the necessary information to calculate the provision accurately.

3.22

The Ministry has improved its guidance in the Kiwi Park model financial statements on cyclical maintenance, which now includes a template to help with the calculation. The Ministry's school sector working group has also discussed the matter with the Ministry's property team. However, if a school does not have reasonable information to base the provision on, it will not be able to come up with a reasonable estimate. Many boards are not considering the long-term maintenance needs of the school as part of their 10-year property plans.

3.23

The 10-year property planning process requires a board to prepare a plan of its cyclical maintenance for the next 10 years, as well as considering capital works. The maintenance plan should inform the school's cyclical maintenance provision. We had hoped that changes to the property planning process introduced a few years ago would produce better quality maintenance plans and therefore more accurate provisions. However, this has not been the case. Our auditors have found that either the 10-year property plan does not include a maintenance plan, or the maintenance plan does not reflect what the school actually intends to do.

3.24

The Ministry approves all 10-year property plans. However, the Ministry does not check that the 10-year property plans include a maintenance plan, even though it is a requirement that a maintenance plan is included. As the focus of both the Ministry and board tends to be on capital works funded by the school's Five-Year-Agreement funding, there is often no review of the maintenance plan for reasonableness, where one is included.

3.25

School boards need to ensure that they base their maintenance provisions on up-to-date information. If a school does have a reliable maintenance plan in its 10-year property plan, it needs to regularly review it to ensure that it is still a fair reflection of the school's maintenance needs. We find that often this is not done, or, if it is done, there is no record of the discussion. If a 10-year property plan is more than three years old, we would expect the board's review of the plan to have input from a properly qualified property professional to ensure that the planned maintenance is still valid. Otherwise a school must provide other evidence to support its provision, such as a quote for painting.

| Recommendation 4 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education ensure that schools are complying with their property planning requirements by having an up-to-date cyclical maintenance plan. The Ministry's review of a school's 10-year property plan should include a review of the cyclical maintenance plan, to ensure that it is reasonable and consistent with the school's condition assessment and any planned capital works. |

Kura kaupapa Māori

3.26

Last year we noted our concerns about financial management and the appropriateness of spending in some kura, a matter we first drew attention to in our Education sector: Results of the 2010/11 audits report. In that report, we identified that the policies and practices in about 20% of kura did not reflect best practice. We continue to see examples of this (see Part 2). Twenty kura (27% of kura) have 2017 audits outstanding, and 10 of these have audits outstanding for other years, some for multiple years. We are working with the kura and the Ministry to get these outstanding audits completed as quickly as possible.

3.27

In our earlier reports we recommended the Ministry monitor how effectively kura and other small schools follow its guidance and, if necessary, provide more targeted guidance. The Ministry has not done so, although it has provided a pilot program in Northland where two accountants were contracted to provide training and support to kura. As we have seen little improvement in the performance of a number of kura, we repeat our recommendation.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education support kura by: • monitoring how effectively kura follow its guidance and, if necessary, provide more targeted guidance; and • continuing to work with those kura that have audits outstanding, to help facilitate the completion of those audits. |

Resource Teacher: Learning & Behaviour clusters and "other activities"

3.28

Resource Teacher: Learning & Behaviour (RTLB) clusters received about $90 million of Ministry funding in 2017. Currently the lead school of a RTLB cluster includes a note in its financial statements setting out the RTLB funding it has received and how it has spent it. We have asked the Ministry to consider the reporting requirements for these clusters and whether the current disclosures in the lead school financial statements are adequate. For example, we know that some of these clusters own assets that are currently not recognised as assets on any school's balance sheet.

3.29

Although we audit the disclosures in the note because it forms part of the school's financial statements, we do not audit the RTLB cluster. The RTLB clusters do provide accountability reports to the Ministry. The depth of our audit work will vary between schools because we carry out our testing in the context of giving an opinion on the school's financial statements. The Ministry needs to consider whether the current accountability arrangements are adequate.

3.30

Schools are also responsible for other activities, including activity centres, Communities of Learning, and other cluster arrangements. There is no guidance for schools on how to account for these separate activities. The reporting requirements usually depend on whether the school board is in a governance position or acting as an agent. Without clear guidance, there is a risk that schools are accounting for these other activities inconsistently.

3.31

In our report last year, we recommended that the Ministry:

- provide guidance to schools on accounting for "other activities" that they receive funding for; and

- consider whether schools should disclose the funding they receive for Communities of Learning separately in their financial statements.

3.32

The Ministry told us that it is still considering this.

Sensitive payments

3.33

We refer to some sensitive payments in Part 2 where we considered them significant enough to report in the school's audit report. If an auditor does not consider a matter significant enough, or it relates mainly to school policies and procedures, the auditor will raise the matter in the school's management letter. Auditors raised the following concerns about sensitive payments in several school management letters:

- schools that did not have sensitive expenditure policies for expenses such as travel and gifts;

- gifts to staff, either without board approval or inconsistent with the school's gift policy; and

- hospitality and entertainment expenses that seemed excessive.

3.34

In our reporting of the 2016 audits, we referred to extravagant gifts and spending on farewells for retiring Principals in the audit reports of three schools. For the 2017 audits, we did not identify any gifts that were significant enough to report on. Our auditors did identify several instances of spending on gifts and hospitality that could be considered excessive. While the board might have approved the payments, the minutes did not record why the board felt the amount given was appropriate. Some of these schools did not have a policy on gifts.

3.35

Following the recommendation in our report last year that the Ministry improve its guidance on giving gifts, the Ministry provided a reminder to schools about gifting in its School Bulletin (30 July 2018).

3.36

A common issue that we come across in schools is spending on credit cards that either is not approved or is approved but not by an appropriate person. Credit cards can be reasonably easily subject to error and fraud or used for inappropriate expenditure. We recommend schools use a "one-up" principle when approving expenses, including credit card spending, meaning the board would need to approve the Principal's expenses. It is important that supporting receipts are provided, reviewed, and retained for all purchases. This also applies to fuel cards or store cards used by schools.

3.37

One of our auditors raised concerns about a school providing a free bus to its students. The costs of the bus were only partly funded by a grant, which meant the school was funding the rest from its operations grant. The auditor was concerned that this was not sustainable. We have seen examples of this in the past, particularly in small schools wishing to increase their roll. It can result in a school getting into financial difficulties, because running a bus can often have unforeseen costs. We also question whether this is a correct use for the school's operations funding.

| Recommendation 6 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education consider providing guidance to schools on the suitability of funding transport services for students who live outside the immediate area of the school. |

Leases

Leasing school equipment

3.38

As noted in Part 2, for the 2017 financial year we have seen an increase in schools breaching the borrowing limit (paragraph 2.40). Most of the leasing arrangements that schools enter into are financing lease arrangements, which is a type of borrowing. The nature of these leases continues to change and although most are presented by the leasing companies as operating leases, on consideration against the relevant accounting standard we have assessed them as finance leases.

3.39

With changing teaching practices there is an increased demand for IT equipment, and decisions about leasing or buying this equipment have become more common. Leasing arrangements often provide added benefits, such as support packages, that schools find useful. Some schools also consider that they are missing out on accessing a good deal because they would breach their borrowing limit, even though they have enough funds to cover the liability.

3.40

Many of the copier contracts that schools are entering into are moving towards total volumes of copies rather than a defined term, but under the contract the school must pay for the total number of copies in the agreement if it wants to end the contract early. Because schools are paying "per copy", it is not always clear that schools understand what they have committed to. As the amounts involved can be significant, this raises concerns about the value for money of some of the contracts.

3.41

Schools are also not always following proper delegations because their boards might have not approved what can be significant contract. We do not often see schools accessing the All-of-Government contracts, which might give them a better deal.

| Recommendation 7 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education provide guidance to schools to help them: • consider whether to lease or buy equipment; and • ensure that they get value for money if they decide to lease, including how to access All-of-Government contracts. |

Schools leasing IT equipment to students

3.42

As we reported last year, we continue to see instances of schools entering into various arrangements to provide access to laptops for their students. This includes leasing laptops and allowing students to pay for them over time, or entering into arrangements with third parties such as computer companies or trusts. We have asked the Ministry on several occasions to provide further guidance on the matter, but it has not done so.

3.43

The Ministry considers schools "leasing" equipment to students to be a breach of legislation. When we identify this situation, we raise the matter in the school's management letter and ask them to discuss it with the Ministry. We have decided that, for the 2018 audits, we will collect information on schools that have these arrangements, so we know the extent of the issue. We will share this information with the Ministry.

| Recommendation 8 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education consider the adequacy of the guidance available to schools on managing laptop schemes for their students, including through a third party. |

Principals' remuneration – concurrence

3.44

In our report on the results of the 2015 school audits we raised concerns about the Ministry's guidance on "principals' remuneration – concurrence". This guidance gives prior approval by the Ministry for certain sensitive payments to principals within clear guidelines, including that any private benefit to the principal should be "incidental". Some schools are not aware of the requirement for concurrence or that, if they are, the board's interpretation of "incidental private benefit" does not always agree with our interpretation.

3.45

We have recommended the Ministry provide guidance to schools on what incidental private benefit is, and expectations of how schools can show that they have complied with the Ministry's circular. The Ministry has not done so. If payments to Principals are made outside the Principal's collective agreement, they are unlawful. Schools also need to consider whether payments meet the principles guiding sensitive payments, and the proper use of public money. Payments should be moderate and conservative and have a justifiable business purpose.

| Recommendation 9 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education give schools practical guidance on how to assess the extent of private benefit for a sensitive payment to a Principal, and how it evidences this assessment, so the school complies with the Ministry's circular. |

Update on previous recommendations and issues raised with the Ministry

3.46

In Appendix 4, we provide an update on the recommendations we raised in our letter to the Secretary for Education about the results of the 2016 audits.

3: Schools with annual total expenditure over $30 million.