Part 3: Country and SAI background information

Country context

3.1

New Zealand is a small country in the South Pacific, made up of two main islands and smaller populated and unpopulated islands.

3.2

As at 30 June 2016, New Zealand’s estimated population is 4.71 million. Around 75% of New Zealand’s population is in the North Island. Auckland is the largest city, with an estimated 34% of New Zealanders living there.3 New Zealand's population growth is slowing but is projected to reach 5.05 million by 2051,4 with Auckland's population expected to reach around 2.5 million by that time.5

3.3

In the 2013 census, people of European ethnicity made up 74% of the population and indigenous Māori made up 15% of the population. Other significant ethnic groups include Asian descent (12%) and Pacific peoples (7%).6 More than half of Māori (53%) identified with two or more ethnic groups, the largest being Pacific peoples (37%).

3.4

New Zealand’s fiscal position is strong, helped by moderate economic growth and restrained government spending. Economic activity, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), grew 0.9% in the June 2016 quarter. This was led largely by construction, which grew by 5%. Growth for the year ended 30 June 2016 was 2.8%.7

3.5

New Zealand is economically reliant on exports of agriculture (especially dairy), fishing, and forestry products. Therefore, the country is vulnerable to fluctuations in global commodity prices, adverse weather, and changes in major export markets, primarily in Australia and China.

3.6

Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), was 0.4% in the year to 30 June 2016. The main contributor to inflation was housing-related prices, which grew by 3.3% for the year. Annual inflation has remained under 2% since December 2011, and at 1% or under since September 2014.8

3.7

Unemployment is currently at 5.1%, with 131,000 people looking for work.9

3.8

In 2015, the average weekly earnings for people in paid employment was $1031 each week. A large pay gap still exists between men (average $1207 per week) and women (average $829 per week). There are also income disparities between ethnicities, with Māori earning an average of $889 per week.10

3.9

The percentage of adults with at least a secondary school education increased steadily from 61.2% in 1991 to 77% in 2015. The number of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher rose from 8.3% in 1991 to 29.8% in 2015.11 From 2009-14, the percentage of students leaving secondary school with no qualification decreased from 19.2% to 13%.12

Country governance arrangements

3.10

New Zealand is a member of the Commonwealth and has a Westminster system of government. Parliament is made up of the House of Representatives and the Queen, represented by the Governor-General.

3.11

Unlike many countries, New Zealand has only one parliamentary house, having abolished its upper house in 1950. Select committees add an extra layer of parliamentary and public scrutiny, serving as a check on the legislative process.

3.12

Elections take place every three years. Since 1996, New Zealand elects its parliament through a mixed member proportional (MMP) system. The public chose MMP over another system, first-past-the-post, through a referendum in 1993. People have two votes under MMP: one for an electorate representative and one for a party. The party vote dictates how many members of Parliament (MPs) each political party can have. Most members of Parliament (71) are electorate MPs. The remainder (50) are list MPs selected by each party and are elected based on each party’s share of the party vote.

3.13

With the exception of the first MMP election in 1996, each election has resulted in largely stable, full-term governments. Since 2008, New Zealand has had a centre-right minority government led by the New Zealand National Party. Before this, New Zealand had a Labour-led centre-left government (first as a coalition, then a minority government) for nine years. The next election is in 2017.

3.14

The executive branch of Ministers is made up of members of the legislative branch. Most Ministers serve in a Cabinet led by the Prime Minister. Members of the support parties have often, in the past several years, been given ministerial portfolios outside of Cabinet. This means they are free from collective Cabinet responsibility and are able to oppose the Government on issues outside their portfolio.

3.15

The executive is supported by a politically-neutral public sector. Public officials are expected to provide free and frank policy advice.

3.16

There is a strict separation of power between the legislative/executive and the judiciary.

Media

3.17

The media in New Zealand includes television, radio, newspapers, news websites, magazines, social media such as Twitter, and blogs. New Zealand also has a Parliamentary Press Gallery. Three large media organisations, New Zealand Media and Entertainment, Fairfax New Zealand, and MediaWorks New Zealand, dominate the media landscape. The press in New Zealand is largely free to work independently without political interference or excessive censorship. This freedom is guaranteed by convention and statute, and supported by freedom of information legislation passed in 1982. In March 2012, Parliament passed the Search and Surveillance Act 2012, which forces journalists to answer police questions, identify sources, and hand over documents.

3.18

The Official Information Act 1982 is an important piece of legislation for journalists. The Act allows all official information – including cabinet papers and officials’ advice to Ministers – to be available on request unless there is good reason for withholding it. The OAG is not subject to the Official Information Act 1982, as the Act would interfere with the Office’s ability to adequately perform its tasks. However, the Office, working in the public interest, endeavours to be of assistance to journalists and the public where it can.

Relationship between the pillars

3.19

In 2013, New Zealand's national integrity systems (NIS) were assessed by Transparency International New Zealand (TINZ).13 This report concluded that New Zealand’s national integrity “remains fundamentally strong,” but that it was “beyond time to take the protection and promotion of integrity in New Zealand more seriously”.

3.20

The report rated New Zealand highly against a wide range of cross-country transparency and good governance measures. The strongest pillars in the NIS were the Office of the Auditor-General (OAG), the judiciary, the Electoral Commission, and the Office of the Ombudsman.

3.21

Key strengths of the pillars included:

- Support for a high-trust society, economy, and policy, and a general culture that does not tolerate overt corruption.

- Wide support for democratic institutions, and elections that are free and fair.

- Overall assurance of the political and civil rights of citizens.

- Infrequent occurrence of significant social, ethnic, religious, and other conflicts. The Treaty of Waitangi protects the rights of the indigenous minority.

- The effectiveness of the judiciary as a check on the executive’s action.

- The effectiveness of the OAG in supporting parliamentary oversight of the public finances.

- The effectiveness of the Office of the Ombudsman as a restraint on the exercise of administrative power and in enforcing citizens' rights of access to information under the Official Information Act 1982.

- When cases of corruption or unethical behaviour by those in power are exposed, the media, political parties, the Auditor-General, law enforcement agencies, and the judiciary usually pursue them vigorously.

3.22

The report identified some weaknesses and concerns in the interactions of various pillars:

- The relationship between political party finances and public funding. Concerns in the report include the transparency of political party financing and of donations to individual politicians, long-term decline in party membership and increased party reliance on public funding, and a lack of full transparency of public funding of the parliamentary wings of the parties. These concerns also influenced the refusal to extend the coverage of the Official Information Act 1982 to the administration of Parliament.

- Parliamentary oversight of the executive, including the use of urgency to pass controversial legislation and the lack of expertise and committees to hold the executive to account.

- Relationship between the political executive and public officials. The report expressed concern about the apparent erosion of the tradition that public servants provide the government of the day with free and frank advice, an apparent weakening over the last decade of the quality of policy advice that public servants provide, and perceived non-merit-based appointments to public boards.

- Interaction between central government and local government. Concerns include intervention by central government in the decision-making authority of local government and weaknesses in the design and implementation of regulations.

Country challenges

3.23

New Zealand faces a number of challenges that have the potential to affect its economic status, social outcomes, and public sector in the medium to long-term. These challenges (unless otherwise cited) were outlined in the Office’s 2013 report, Public sector financial sustainability.14

3.24

Demographic changes. Like other developed nations, New Zealand’s population is ageing. By 2051, half of the population is expected to be 46 years old or older, and one in four New Zealanders will be 65 years and over. At the national level, the main concerns of an ageing population are the sustainability of a taxpayer-funded superannuation and the increased cost of health services. At the regional and local levels, there are concerns about planning for housing and accommodation and providing aged-care, transport, and community services.15 Combined with the growth in health spending – faster than GDP growth – population change is putting greater pressure on the sustainability of public sector finances.

3.25

Economic performance. Although New Zealand’s debt position is relatively positive compared to other countries, a persistent current-account deficit could cause payment problems in the event of a sudden outflow of capital. Partly because of the country’s isolation, and despite some useful enablers such as good education and ease of doing business, private sector productivity improvements have remained modest in the past 50 years. New Zealand remains a service and resource-based economy and has not yet translated favourable commodity prices into investment in better-value additions through, for example, processing raw products.

3.26

High and increasing private debt. New Zealanders have spent more than they have earned in all but four of the last 55 years, as measured by the current-account deficit. Household debt is high and rising, comparable with some of the more stressed OECD countries. Overall, debt has been at 70-80% of GDP since 2000, and household debt to income ratio has risen from 100% to 140% between 2000 and 2012.

3.27

Unsustainable social spending. In its 2013 report Affording Our Future: Statement on New Zealand's Long-term Fiscal Position,16 the Treasury identified two main areas of government spending that are expected to grow significantly: healthcare and superannuation. From about 2030, the projection indicates that the Government will need to borrow an increasing amount to balance its budget, based on current policy settings. If nothing is done to address the growing deficit, then debt-financing costs in 2060 are projected to be 11.7% of GDP a year and net debt is projected to be 198.3% of GDP.

3.28

Increasing inequality. Evidence suggests that income inequality is associated with a wide range of undesirable outcomes and consequent public costs. In terms of market income, New Zealand has moved from being one of the most equal countries in the OECD, 30 years ago, to being one of the least equal today. There also appears to be an increasing range of at-risk groups, mainly youth (as shown by high youth suicide, teen fertility, and unemployment rates).

3.29

Child poverty. Child poverty is an issue in New Zealand. A commonly used income poverty threshold is a household equivalent disposable income of less than 60% of the median income, after adjusting for housing costs. Using the relative threshold measure (comparing incomes in a given year to the median income in the same year), 305,000 (29%) of dependent 0–17 year olds were living in income poverty in 2014. This is up from 260,000 (24%) in 2013.17

3.30

The OECD Economic Survey of New Zealand 201518 expanded on these challenges and identified others below.

3.31

Rapid population growth and a low responsiveness of supply have led to housing and urban infrastructure constraints. In particular, house prices have risen sharply in Auckland, the largest city, eroding affordability and raising financial-stability risks. Efforts to speed the housing supply response have been made, although community resistance to rezoning and densification may limit development. (Auckland Council has recently approved the Auckland Unitary Plan, which requires the building of 422,000 new houses by 2040.)

3.32

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution. New Zealand faces difficult climate change challenges because of the high share of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions coming from agriculture, where there are few cost-effective abatement possibilities, and because three quarters of electricity already comes from renewable sources, meaning there are fewer potential gains in generation. Water quality in some regions has suffered from the steady expansion of intensive dairy farming. Both industry and government have responded, but it is not yet clear if these measures will prove sufficient.

3.33

Making economic growth more inclusive. Income inequality, reflecting in part unequal employment prospects, is above the OECD average. Recent welfare reforms facilitate the transition of beneficiaries into employment, but a greater focus is needed on improving the long-term outcomes of the most disadvantaged New Zealanders across the public sector. The government is taking steps to ease shortages of affordable and social housing but will need to go further to make significant headway in rolling back the large increase in the burden of housing costs on low-income households in recent decades.

Overview of the public sector

Public sector structure

3.34

New Zealand’s public sector consists of a number of different organisational forms. These vary in the extent to which they are at an arm's-length from Ministers, how they are governed, and the expectations that apply. For example, public service departments are close to Ministers (part of the legal Crown), and Crown entities are stand-alone corporate bodies that operate at arm's-length. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are Crown-owned but required to operate as a commercial business and return a profit to the Crown. Mixed ownership model companies are similar except they are partly in private ownership (up to 49%). Most Crown entities are part of the State services, but tertiary education institutions are part of the wider State sector.

3.35

See the public sector map below,19 and the “Glossary of terms used in public sector map”20 for more information about the different types of public entities.

Public sector budget

3.36

The Treasury sets out the total of each appropriation for 2015/16 (final budgeted and estimated actual) and for 2016/17 (departmental and non-departmental transaction budgets).21

3.37

The following diagram presents the important aspects of the 2016.17 budget.

Revenue and expenditure

3.38

The Core Crown revenue forecast for 2016/17 is $78.5 billion. The Treasury’s “Budget at a Glance 2016”22 sets out New Zealand’s sources of revenue as follows:

- Individuals tax: $32.5 billion.

- Goods and Services Tax (GST): $19.1 billion.

- Corporate tax: $11.6 billion.

- Other indirect tax (such as customs, excise and gaming duties): $6.5 billon.

- Other revenue: $3.3 billion.

- Interest, revenue, and dividends: $3.3 billion.

- Other direct tax (such as resident interest and dividend withholding taxes): $2.2 billion.

3.39

Core Crown expenses forecast for 2016/17 are $77.4 billion. This is broken down as follows:

- Health: $16.2 billion.

- Education: $13.5 billion.

- New Zealand Superannuation: $12.9 billion.

- Social security and welfare: $12.3 billion.

- Core government services: $4.9 billion.

- Law and order: $3.8 billion.

- Finance costs: $3.7 billion.

- Other: $10.1 billion.

3.40

The below graph shows the Crown’s operating balance between 2009 and 2015.

Local government

3.41

Local authorities contribute a significant amount to New Zealand’s economy. The Government Finance Statistics (Local Government) for the year ended June 2015 showed that compared with the previous year:

- There was a net operating surplus of $1.0 billion for local government.

- Operating income increased 6.6% to $9.7 billion, and expenses increased 6.2% to $8.7 billion.

- The net acquisition of non-financial assets, including infrastructure, totalled $1.8 billion.

- Net borrowing was $0.8 billion, up from $0.7 billion in 2014.23

- Total assets increased $5.5 billion, to $125.9 billion, mostly due to upward revaluations.

- Total liabilities increased $2.0 billion, to $15.6 billion.

- Total net worth was $110.3 billion, up from $106.8 billion in 2014.

New Zealand’s public financial management and governance

3.42

New Zealand’s public management system is seen as world class, with strong accountability foundations.

3.43

Major public sector reforms in the 1980s and 1990s laid the foundations for New Zealand’s financial management system today. The changes introduced requirements for service delivery entities to report on service performance, for the government to consolidate its activities and show these in one set of financial statements, and for the public sector to comply with generally accepted accounting practice (GAAP). GAAP is determined by an independent standard setting body, the External Reporting Board (XRB).

3.44

The State Sector Act 1988 sets out the operation of the public service, and the responsibilities of chief executives of government departments to their Minister for the performance of their departments’ functions.

3.45

The Public Finance Act 1989 established a system for financial appropriations to be approved by Parliament and monitored by the Controller and Auditor-General. It also set out principles of responsible financial management, and gave detailed requirements for strategic planning and financial and service performance reporting.

3.46

In 1992, New Zealand was the first country to fully implement accrual accounting in its public sector.

3.47

These, and other changes, ensured that the government and public sector leaders had much more useful financial and performance information to make better medium and long-term policy decisions.

3.48

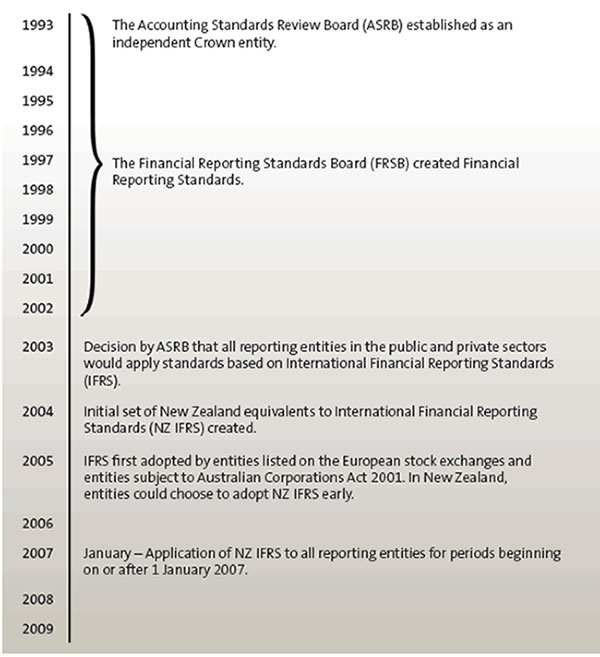

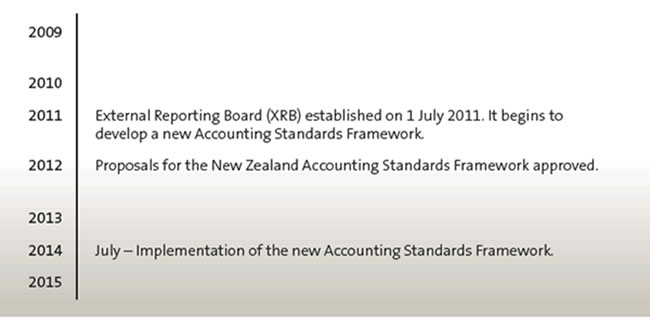

Accounting and reporting standards in New Zealand have evolved substantially in the past two decades. The International Financial Reporting Standards, designed for commercial companies listed on stock exchanges, were introduced in 2005 and proved to be unsuitable for much of the public sector. The below timeline looks at the development of accounting standards in New Zealand between 1993 and 2009.24

3.49

In 2011, the XRB was set up as an independent Crown entity to develop and issue accounting, auditing, and assurance standards in New Zealand. The XRB is largely responsible for the implementation of the new Accounting Standards Framework. The framework distinguishes between accounting standards for public benefit entities (PBE accounting standards) and standards for commercially focused entities.

3.50

The Accounting Standards Framework uses tiers so that financial reporting requirements reflect the different size and nature of reporting entities. This tiered structure is likely to help smaller entities achieve a better balance between the costs and benefits of general purpose financial reporting. The public sector now has the opportunity to remove unnecessary clutter from its reporting, focusing instead on users’ information needs and what matters most to them.

3.51

The following timeline sets out the significant changes to accounting standards since 2009. A fuller history of New Zealand’s accounting standards is available in the Office’s 2016 report, Improving financial reporting in the public sector.

3.52

Audit reports are also evolving to help users better understand, and focus on, the important issues. A “key audit matters” section is included in some audit reports and the FSG at the discretion of the Auditor-General. Key audit matters highlight the most significant issues, and how they are addressed, in a succinct and easy to understand way.

3.53

New Zealand enjoys a positive reputation for the strength of its public management framework. New Zealand has been ranked in or above the 90th percentile for all of the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators since 2009 (when one of the six indicators, political stability, was in the 80th percentile).

3.54

The following graph shows New Zealand’s ranking in the Worldwide Governance Indicators between 2010 and 2014.25

3.55

There are some emerging risks to New Zealand’s reputation. From 2006 to 2013, New Zealand ranked either first or first equal on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index. New Zealand’s ranking slipped to second in 2014, and then to fourth in 2015.26

3.56

The International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Survey (OBS) measures budget transparency, participation, and oversight. The OBS uses 109 indicators to assess “whether the central government makes eight key budget documents available to the public in a timely manner and whether the data contained in these documents are comprehensive and useful.”27

3.57

New Zealand scored first in the world for transparency, with 88 out of 100. For budget oversight by the supreme audit institution, it scored 92. For public participation (defined as “the Government of New Zealand provides the public with adequate opportunities to engage in the budget process”), New Zealand scored just 65. For budget oversight by the legislature, it scored 45.

3.58

The OBS recommends taking these actions to improve budget participation:

- Establish formal regulations that oblige the executive to engage with the public during each stage of the budget cycle.

- Hold legislative hearings on the budgets of specific ministries, departments, and agencies at which testimony from the public is heard.

- Provide detailed feedback on how public assistance and participation have been used by the supreme audit institution.

3.59

To improve parliamentary oversight, OBS recommends establishing “a specialised budget research office for the legislature.”

3.60

The Controller and Auditor-General and the Deputy Controller and Auditor-General are both officers of Parliament. Their mandate and responsibilities are set out in the Public Audit Act 2001. The OAG follows the Legislative model.

3.61

The Auditor-General reports to the Speaker of the House, not to a Minister or the executive. Budgets are set in the Officers of Parliament Committee, not the government of the day. The Office is free to appoint its own staff and set its own staff remuneration.

3.62

The Public Audit Act 2001 states the Auditor-General must act independently in exercising the functions, duties, and powers of the Office. The Auditor-General is accountable to Parliament for the management of public resources entrusted to them. The independence and mandate of the Auditor-General is discussed in Part 4, Domain A of this report.

New Zealand’s SAI’s framework, organisational structure, and resources

The Auditor-General’s vision

3.63

The Auditor-General’s vision is for the Office’s work to improve the performance of, and the public's trust in, the public sector. Everything the Office does is directed at ensuring that New Zealand has a public sector that is trusted, demonstrates responsible behaviour, and performs well.

3.64

The Office’s outcomes framework summarises its aims, the effects it aims to have, and the services that it provides.

The Office’s work

The Controller function

3.65

The Controller function provides independent assurance to Parliament that spending by government departments and Offices of Parliament is lawful, and is in the scope, amount, and period of the appropriation or other authority.

3.66

In keeping with the Auditor-General's Auditing Standards and a Memorandum of Understanding with the Treasury, the OAG and appointed auditors carry out standard procedures for the Controller function. They review monthly reports that the Treasury provides and inform them of any problems and advise the action to be taken.

3.67

The Auditor-General reports to Parliament each year on any significant matters related to the Controller function.

The auditor function

3.68

The Auditor-General has a mandate to perform several types of audits and other work.

3.69

Financial audits: By law, the Auditor-General audits all public entities in New Zealand that prepare separate general purpose financial reports; this is about 3700 public entities. They include government departments, Crown entities, schools, local authorities, and State-owned enterprises. The Auditor-General provides assurance to Parliament and the public that public sector organisations are operating, and accounting for their performance, in accordance with Parliament’s intentions. These financial audits make up about 87% of the Office’s workload. The Office also completes a small number of compliance audits in conjunction with the annual financial audit. These audits assess compliance with various regulatory and external reporting obligations. This includes the audit of debenture trust deeds, energy regulation disclosures, and tertiary education sector performance-based research funds.

3.70

Performance audits: The Office’s mandate allows it to audit the performance of all public entities. These reports identify good practices, raise any issues or concerns, and recommend improvements where necessary. The Office completes around 12 performance audits each year, as well as follow-ups to see if recommendations have been implemented. Often, Parliament’s select committees will invite the Office to brief them on these reports. The Office reports its findings and helps the committee to hold the public entities to account for implementing its recommendations. The Office will usually follow up about 18 months after the report to see what progress has been made. The Office also presents these findings to Parliament.

3.71

Since 2012/13, the Office has applied a theme across its work, particularly in its performance audits. The annual themes have been:

- 2012/13: Our future needs – is the public sector ready?

- 2013/14: Service delivery.

- 2014/15: Governance and accountability.

- 2015/16: Investment and asset management.

- 2016/17: Information.

- 2017/18: Water (proposed).

3.72

After consulting with Parliament on the proposed programme of work, the Office publishes in its Annual Plan the work the Auditor-General intends to carry out.

3.73

Inquiries: The Office can look into issues of concern. These can either be raised by anyone or the Office can initiate an inquiry. The Auditor-General has discretion over what the Office looks into – no one can force the Auditor-General to investigate a matter. Routine inquiries are small and mostly involve a review of relevant documents and talking to the organisation. They are expected to be completed within three months. The Office aims to complete significant inquiries within six months. Major inquiries, which are bigger in scope still, and have formal terms of reference. These are expected to be completed within 12 months. Major inquiries are published as reports and tabled in Parliament. In 2015/16, the Office completed work on 185 inquiries and other issues. Most were routine inquiries and five were significant.28

3.74

Factors that help the Office decide whether to inquire include:

- issues of financial impropriety;

- problems with governance or management; or

- other systemic concerns that may be important for the organisation, the sector, or the general public.29

3.75

Other factors include the seriousness of the issue, whether the Office has the resources to consider it properly, and whether the matter can be addressed through other avenues. These avenues include the Office of the Ombudsman and the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (which are both also officers of Parliament), State Services Commission, New Zealand Police, and the Serious Fraud Office.

3.76

Other work: This includes overseeing the Local Authorities (Members’ Interests) Act 1968, where the Office considers applications from elected members to participate in matters where they have a pecuniary interest or enter into contracts with their local authority worth more than $25,000 a year; the audit of local authorities’ long-term plans; sector reports, where the Office identifies trends and behaviours from each sector; and publishing fraud data, including the types, methods and reasons, and how fraud was detected; and an annual reflections report, which draws together insights and findings from the work performed under the annual theme.

Relationship with Parliament

3.77

Parliament is the Office’s primary stakeholder. The Office‘s obligations to Parliament under the Public Audit Act 2001 include:

- submitting its draft Annual Plan to Parliament and consulting with members of Parliament about proposed performance audits, although the Auditor-General still has the final say;

- preparing and presenting to Parliament an annual report that includes audited financial statements;

- submitting its annual budget to Parliament through the Speaker; and

- presenting reports in Parliament before they are publicly released, although the gap between these steps is often no longer than a few minutes.

3.78

The Office’s advice and support assists Parliament in its scrutiny of the performance and accountability of public entities. The Office uses information from its annual audits and performance audits to advise and inform Parliament and its other stakeholders. The Office’s reporting and advice to Parliament identifies and addresses issues and risks in the public sector.

3.79

The Office’s advice and support includes:

- reports and advice to select committees for their annual reviews of public entities and their examination of votes within the Estimates of Appropriations; and

- reports to Parliament on matters arising from its annual audits.

3.80

The Office also reports to Ministers on the results of the annual audits for public entities in their portfolio.

Limits to mandate

3.81

There are limits to the Auditor-General’s mandate. The Office cannot comment on policy matters. Also, if a private organisation is receiving funding from a public entity, the Office needs to focus on how the public entity is managing the relationship and monitoring deliverables under the funding agreement. Apart from matters arising under the Local Authorities (Members’ Interests) Act 1968, the Office’s main power is to report; it cannot make anyone act on its recommendations or overturn decisions. The Office also cannot carry out performance audits or inquiries into the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

The Office’s international contribution

3.82

Each year, the Office makes a significant international contribution. It aims to strengthen public sector accountability and promote good governance by sharing its skills, information, and advice with other audit bodies throughout the world, particularly in the Pacific region.

3.83

The Office supports accountability, transparency, and good governance in the Pacific through its commitment to PASAI, which is the Pacific region working group of INTOSAI. The Auditor-General and the Office support the PASAI secretariat in their work. The Auditor-General is the Secretary-General of PASAI and has represented PASAI on the governing board of INTOSAI up to this year.30 The Office has received funding from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) for the last five years to provide PASAI support, and has recently negotiated a further contract with MFAT to continue this support from 2016-19.

3.84

The Office often hosts international delegations in order to exchange information and build networks. Over the past couple of years, it has assisted representatives from the Parliaments, Treasuries, and/or Audit Offices of Tonga, Samoa, Vietnam, Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The Office has provided a comprehensive international secondment programme to assist the Audit Board of the Republic of Indonesia in its transition to accrual accounting. The Office also operates an arrangement between the Samoan and Cook Islands audit offices to assist their development.

The Office’s structure

3.85

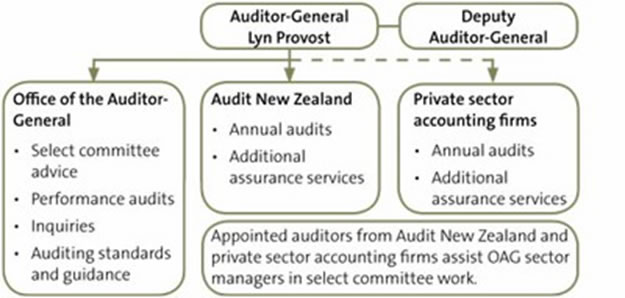

The work of the Controller and Auditor-General is carried out by the OAG, Audit New Zealand, a shared corporate services team, and private sector auditing firms.

3.86

The Office’s work is carried out by about 370 full-time equivalent staff in two business units – the OAG and Audit New Zealand. They are supported by a shared team of corporate services staff, along with appointed auditors and their staff from about 50 other audit service providers.

3.87

The Annual Report 2015/16 explains the role of the two business units:

The Office of the Auditor-General sets strategy, policy, and standards; appoints and oversees auditors; carries out performance audits; provides reports and advice to Parliament; and carries out inquiries and other research.

Audit New Zealand, the larger of the two business units, has offices in seven cities and carries out annual audits of public entities that the Auditor-General allocates to it. Audit New Zealand provides other assurance services to public entities within the Auditor-General's mandate, consistent with the Auditor-General's auditing standard on the independence of auditors.31

3.88

The Executive Director of Audit New Zealand reports to the Auditor-General.

3.89 There are six teams in the OAG:

- Accounting and Auditing Policy;

- Legal;

- Local Government;

- Parliamentary;

- Performance Audit; and

- Research and Development.

3.90

Each team is led by an Assistant Auditor-General.

3.91 One Corporate Services Team, also led by an Assistant Auditor-General, supports both the OAG and Audit New Zealand.

3.92

The OAG’s Leadership Team includes:

- the Auditor-General;

- the Deputy Auditor-General; and

- each of the Assistant Auditors-General.

3.93

The OAG Leadership Team considers all OAG business and work programme matters. The Executive Director of Audit New Zealand ensures that, where relevant, information flows freely between the OAG and Audit New Zealand.

3.94

Appointed auditors from about 50 private sector accounting firms are contracted to carry out some annual audits on the Auditor-General's behalf. These firms are called audit service providers. When allocating audits to audit service providers, six principles are applied. The principles are designed to ensure that auditors are independent, audits are of a high quality, and audit fees are reasonable. Another important principle is that auditing firms have sufficient audits allocated to them to ensure critical mass and Audit New Zealand is maintained as a strong and viable audit service provider. The Office continually monitors the allocation of audits to ensure that these principles are followed.

3.95

The below diagram sets out the relationship between each business unit and other audit service providers:

3.96

The Auditor-General remains accountable for audit quality and ensuring that audits are performed effectively, efficiently, and in line with professional accounting and auditing standards. The Auditor-General’s Auditing Standards establish the minimum standards to be applied to work carried out on their behalf. All auditors in New Zealand are required to adhere to the standards set by the XRB.

3.97

The following table sets out staff numbers and staff diversity between 2011 and 2016:

| As at 30 June | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff numbers (full-time equivalents) | ||||||

| Office of the Auditor-General | 64 | 73 | 68 | 71 | 72 | 74 |

| Audit New Zealand | 252 | 254 | 253 | 247 | 267 | 247 |

| Corporate Services | 46 | 48 | 48 | 50 | 52 | 46 |

| Total | 362 | 374 | 369 | 369 | 391 | 367 |

| Functional distribution | ||||||

| Audit/assurance | 65% | 64% | 65% | 64% | 64% | 63% |

| Technical and advisory | 11% | 11% | 10% | 11% | 11% | 14% |

| Corporate support | 21% | 22% | 22% | 22% | 22% | 20% |

| Senior management | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Gender distribution – all staff | ||||||

| Women | 53% | 53% | 54% | 55% | 53% | 54% |

| Men | 47% | 47% | 46% | 45% | 47% | 46% |

| Gender distribution – executive management | ||||||

| Women | 50% | 42% | 42% | 42% | 36% | 42% |

| Men | 50% | 58% | 58% | 58% | 64% | 58% |

| Ethnicity distribution | ||||||

| NZ European | 49% | 53% | 49% | 48% | 44% | 47% |

| NZ Māori | 2% | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Pacific Islander | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Asian | 10% | 12% | 11% | 13% | 15% | 16% |

| Other European | 12% | 14% | 14% | 13% | 12% | 15% |

| Other ethnic groups | 7% | 4% | 10% | 8% | 7% | 11% |

| Undeclared | 18% | 11% | 9% | 13% | 16% | 6% |

3.98

The Office is funded through Vote Audit, which has five separate appropriations:

- Audit and Assurance Services RDA (revenue dependent appropriation), intended to provide for audit services to all public entities (except smaller public entities) and other audit-related assurance services.

- Audit and Assurance Services, intended to provide for audits and assurance of small entities, such as cemetery trusts and reserve boards, funded by the Crown.

- Statutory Auditor Function MCA (multi-category appropriation), to support Parliament in ensuring accountability for the use of public resources.

- Remuneration of Auditor-General and Deputy Auditor-General PLA (permanent legislative authority).

- Controller and Auditor-General – Capital Expenditure PLA, which is limited to the purchase of assets by, and for the use of, the Controller and Auditor-General.

3.99

The appropriation for Audit and Assurance Services enables the Office to carry out audits and related assurance services as authorised by law. This is largely funded by audit fees collected from public entities.

3.100

The multi-category appropriation Statutory Auditor Function is largely Crown-funded and includes:

- Services to Parliament – providing advice and reports to help select committees and other stakeholders;

- Controller function – providing assurance to Parliament that public money has been spent lawfully and within the authority provided by Parliament; and

- Reports, studies, and inquiries – reporting on the results of annual audits, performance audits, and other studies, and inquiring into a public entity's use of its resources.

3.101

The funding for each appropriation, expenditure, and full financial statements are published each year in the Office’s annual report. The 2015/16 Annual Report was published in September 2016.32

3.102

In 2014/15, the Office received additional funding from the Crown to establish a dedicated inquiries team to handle the growing demand (from members of Parliament and the public) for inquiries and to increase the Office’s data analysis capability.

3: See www.stats.govt.nz.

4: See www.stats.govt.nz.

5: See Auckland Council Draft Plan: www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz.

6: See www.stats.govt.nz.

7: See www.stats.govt.nz.

8: See www.stats.govt.nz.

9: See www.stats.govt.nz.

10: See nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz.

10: See nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz.

11: See www.stats.govt.nz.

12: See www.kidscan.org.nz.

13: See www.transparency.org.nz.

14: Available at www.oag.govt.nz/2013.

15: See www.stats.govt.nz.

16: See www.treasury.govt.nz.

17: See www.nzchildren.co.nz.

18: See www.oecd.org.

19: See www.ssc.govt.nz.

20: See www.ssc.govt.nz.

21: See www.treasury.govt.nz.

22: See www.treasury.govt.nz.

23: The gross debt of local authorities at 30 June 2015 was $12.3 billion. Refer to http://www.oag.govt.nz/2016/local-govt, page 11.

24: See the Office’s 2016 report, Improving financial reporting in the public sector, available at www.oag.govt.nz.

25: See info.worldbank.org/ and www.oag.govt.nz/.

26: See www.transparency.org.

27: See “Country Summary” at www.internationalbudget.org.

28: See the Office’s annual report for 2015/16, available at www.oag.govt.nz.

29: See the inquiries section in “Our work”, at www.oag.govt.nz.

30: This role has now passed to the Auditor-General of Samoa, following a vote of the PASAI Congress in August 2016. The Auditor-General of Samoa has been mentored by New Zealand in preparation for this handover.

31: Available at www.oag.govt.nz.

32: All the Office’s annual reports are available at www.oag.govt.nz.