New Central Library

1. Introduction

1.1

The theme for our work programme in 2014/15 was Governance and accountability. We chose this theme because of recent significant changes in legislation and financial reporting standards that affect public sector accountability arrangements. Good governance is important for achieving successful outcomes for major projects.

1.2

We audited three projects that are part of the Canterbury earthquake recovery. The recovery has long-term implications for people’s lives as well as the economy. Rebuilding Canterbury is a priority for the Government and is a significant area of public spending. Strong governance is needed to ensure that public funds are spent appropriately, that entities are working together to deliver intended outcomes, and to provide clear accountability for Cantabrians and all New Zealanders.

1.3

The three projects we audited were the Bus Interchange, the New Central Library, and the Acute Services Building at Christchurch Hospital. This document reports our findings and conclusions for the New Central Library project.

1.4

We have assessed the governance and accountability arrangements of the three projects against six principles of good governance. We identified these principles by drawing on some of our previous reports as well as other relevant literature. Figure 1 sets out the six principles.

Figure 1

Principles of good governance

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Clarity of purpose | Governance sets a clear strategic purpose for the entity or project and provides direction that drives the entity towards achieving that purpose. |

| Accountability | The governance structure includes a clear accountability framework. |

| Roles and responsibilities | Each part of the governance structure has clear roles and responsibilities that are complementary and aligned with strategy. |

| Leadership | Leadership is demonstrated across all levels of governance. |

| Information and reporting | The governance arrangements are supported by information and reporting for monitoring performance, managing risks, making decisions, and providing direction. |

| Capability and participation | The right people are involved in governance. |

Governance arrangements for the New Central Library project

1.5

At the time of our audit in December 2014, Christchurch City Council (the Council) identified that the Project Control Group was the main group providing governance to the New Central Library project. Therefore, our audit focused on the Project Control Group.

1.6

However, one of our main findings was that, in practice, the Project Control Group acted in a management role. We were unable to identify any group or individual that had a specific role in providing governance of this project beyond existing day-to-day line management roles and responsibilities. We also identified several weaknesses in the way the Project Control Group operated.

1.7

Since then, the Council has made several changes to strengthen its governance of the New Central Library project. These changes include setting up a new Project Steering Group to provide governance. The extent of the changes means that our findings from December 2014 do not reflect the current governance arrangements for the project.

1.8

We decided to update our findings by reviewing the new arrangements. This work included reviewing documentation about the new Project Steering Group, observing a Project Steering Group meeting, and interviewing members of the Project Steering Group and Council management. This enabled us to make a judgement about whether the new arrangements are effective and address the weaknesses we identified earlier. We did this work in October 2015.

1.9

This document presents our findings from December 2014. Where applicable, it also presents our findings from October 2015. We show these under separate sub-headings for December 2014 or October 2015.

1.10

The elected councillors provide the highest level of governance of the project. They have the authority to make decisions that will determine the type of library that will be built and how much they can spend on it. To make the best decisions they can, councillors need reliable and relevant advice and information. Providing this advice is one of the main roles of a governance group at a project level. This is the level of governance our audit focused on.

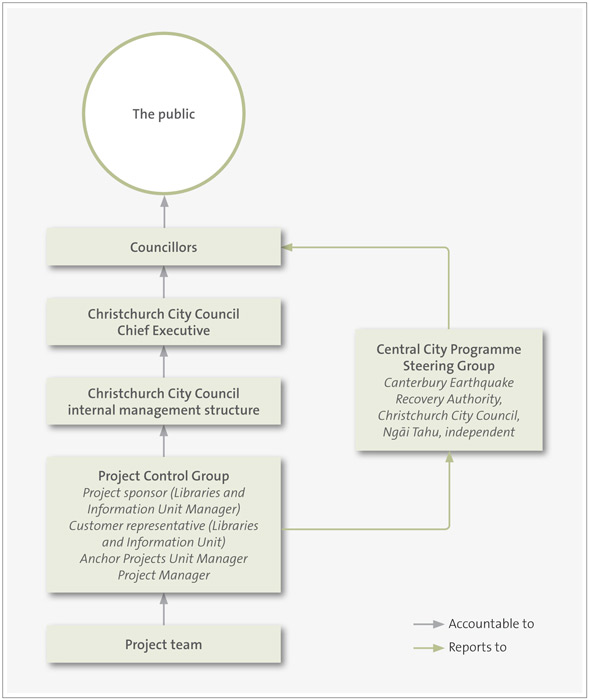

1.11

Figure 2 shows our interpretation of the management and governance structure for the project when we did our audit in December 2014. In the documents we reviewed, we could not find a diagram of the structure that accurately reflected the arrangements we found in practice. Our interpretation is based on information we gathered from interviews and document reviews.

Figure 2

New Central Library project governance structure, December 2014

Source: Office of the Auditor-General

1.12

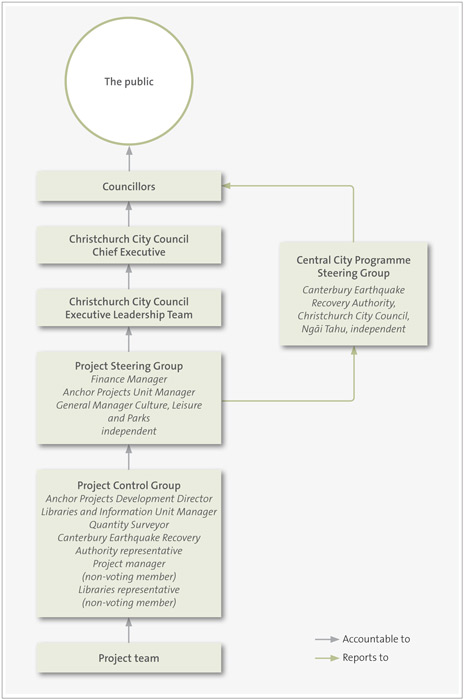

Figure 3 shows the new governance arrangements that have been put in place.

Figure 3

New Central Library project governance structure, October 2015

Source: Office of the Auditor-General

Overall findings

1.13

In December 2014, the governance and accountability arrangements for the New Central Library were not consistent with the principles of good governance. In particular, we did not consider that the arrangements had been designed in a way that provided adequate independent oversight and leadership of the project.

1.14

The Project Control Group was acting as a management group and no group provided governance oversight of the project below the level of councillors. The Project Control Group was not providing adequate leadership for critical project risks. Risk management in general was weak, and reporting lacked focus and consistency.

1.15

These findings did not necessarily mean that the project would fail. In fact, the project had made good progress at that time. However, without strengthening the governance arrangements, there was a significant risk that the project would fail to deliver its objectives on time and on budget. We found that some significant risks with funding and affordability were not being addressed.

1.16

The Council recognised that there were weaknesses with its governance arrangements for the New Central Library project. The Council appointed a new Development Director to make some improvements. These improvements included:

- setting up a Project Steering Group that has a clear project governance role;

- bringing people from other parts of the Council and with more governance experience into the Project Steering Group;

- appointing an independent chairperson to the Project Steering Group;

- appointing external project managers;

- clarifying roles and responsibilities; and

- making improvements to reporting.

1.17

The new Project Steering Group has been in place only since August 2015 and so has had limited opportunity to demonstrate its effectiveness. However, based on the work we did in October 2015, we are satisfied that the new arrangements are a definite improvement on the arrangements we saw in December 2014. We found more clarity with the project’s governance arrangements, improved reporting, and a separation of management and governance.

1.18

We also saw more leadership of project risks. In particular, the Council has carried out several steps to mitigate the funding and affordability risks. The New Central Library project has now taken more ownership of these risks, there are plans in place to manage them, and information about the risks is being communicated to the right people.

2. Clarity of purpose

Why is clarity of purpose important?

2.1

People that set direction for projects need to clearly understand the project’s purpose, including the limits to what they have to do and the project’s intended outcomes. They must also be able to understand the influence of their decisions and actions. If they do, goals are more likely to be met and intended outcomes achieved.

2.2

Individually and together, people in governance positions need to focus on more than just the reports on the project. They need to think at a strategic level, disseminate that thinking, and understand the effects of their direction.

The project has a clear strategic purpose

2.3

There is a clear strategic purpose for the project. The project business case, which councillors approved on 26 March 2015, is detailed, with a clear purpose and objectives for building the new library. These objectives are for the library to:

- develop a strong community and sense of place;

- contribute to the knowledge economy;

- celebrate and preserve culture and heritage; and

- act as a catalyst for the regeneration of Christchurch.

2.4

The business case also shows how the new library will fit into the Council’s library services and the overall strategic context for Christchurch, including the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan. The library has a clear role in the regeneration of Christchurch and is described as “central to the city’s future”.

The arrangements lacked clarity

December 2014

2.5

In December 2014, the project’s governance and management arrangements were not as clear as its purpose. There were no clear objectives for the Project Control Group. In the documents we saw, we found confusion about whether the group had a governance or management role. We found that the people we interviewed were similarly confused. In our view, the Project Control Group was acting as a management group, rather than a governance group.

2.6

We expected to see a clear purpose for the Project Control Group, such as whether it was there to monitor, advise, or make decisions. We also expected to see an explanation of relationships between the Project Control Group and other groups and individuals with a governance or management role in the project.

2.7

Project Control Group members we spoke to had a good understanding of the project’s purpose and goals. However, without a good understanding of what the Project Control Group is there for, members may not understand their role in achieving the project’s intended outcomes.

2.8

Project documentation was not clear about the role that the Central City Programme Steering Group has for the project. This group provides governance at a programme level for the Christchurch Central Delivery Programme. The group is run by the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) but includes representatives from the Council and Ngāi Tahu, as well as independent members.

2.9

The Central City Programme Steering Group is an advisory group that monitors and helps co-ordinate all public sector rebuild projects and oversees programme-level risks. However, the New Central Library project business case states that the Central City Programme Steering Group is responsible for project governance. We did not see any explanation of what this involves. Nor did we see how the role of the Central City Programme Steering Group interacts with the role of the Council, which has ultimate control of, and accountability for, the project.

October 2015

2.10

In October 2015, the new Project Steering Group has a clear purpose to provide governance oversight of the project. This is explained in its terms of reference. We spoke to all the members of the group, and they had a good understanding of the group’s purpose. They understood how it differed from the Project Control Group, which now has a clear management role.

3. Accountability

Why is accountability important?

3.1

Public accountability is how authorities using public resources explain their activities:

The level of citizen trust in the ability and motivation of decision-makers in authority determines how well society works. If decision-makers are required to explain their intentions, reasons and performance standards publicly, fully and fairly before they act, citizens can act fairly and sensibly to commend, alter or halt the intentions.1

3.2

Who is accountable for what, and who they are accountable to, needs to be clear. Everyone involved in the activity should understand the accountability framework.

3.3

When projects are funded by public money, the public has the right to know whether that money is well spent. If accountability is unclear, they cannot know who is ultimately responsible for the results.

3.4

Being accountable to the public means keeping the public informed about important decisions, how the project is progressing, and what results are being achieved. The public are often asked for their views about what they want from a project. Decision-makers should ensure that the public’s views are heard. The decision-makers should then tell the public how they have acted on those views.

Accountabilities were not clearly defined

December 2014

3.5

In December 2014, accountabilities for this project were not clearly defined or well understood. The Council is ultimately accountable for the project under the Cost Sharing Agreement between the Crown and the Council. Line management relationships were also assumed to provide some of the accountabilities.

3.6

We did not see anything that reliably said what the accountabilities were for the Project Control Group or individuals with specific project roles. People we spoke to were clear about their reporting lines but not what they were accountable for.

3.7

In our interviews, project team members and the Project Control Group showed a good understanding of when full Council approval is required. However, project documents did not explain this. There are clear financial delegations, but criteria for escalating non-financial decisions are not specified.

3.8

We expected to see a clear accountability framework. This information is often recorded alongside roles and responsibilities in a document, such as terms of reference. An accountability framework should include who is accountable, who they are accountable to, what they are accountable for, and how they will be held to account. We also expected to see people in both management and governance roles being held to account in keeping with the framework.

October 2015

3.9

In October 2015, we found more clarity about accountabilities, but there was still room for improvement. The Project Steering Group’s terms of reference list the group’s responsibilities and who it reports to. However, accountabilities were not documented beyond that.

3.10

Several people told us that they were not clear about who is accountable for the project at a more senior level. However, they did explain that, within the Facilities and Infrastructure Rebuild Group, which is responsible for project delivery, accountabilities are aligned with people’s job descriptions and these are well understood.

3.11

In our view, the Council would benefit from clarifying project accountability so that people can be certain about who is accountable for delivering the project to completion.

Consultation with the public was comprehensive and transparent

3.12

Public consultation for the New Central Library has been open and comprehensive. Initial public consultation for the rebuild of central Christchurch was through the award-winning Share an Idea campaign.

3.13

This was followed by Your Library, Your Voice, which asked people what they wanted to see in the New Central Library. Your Library, Your Voice received more than 2400 ideas from the public, all of which have been published.

3.14

Information released about the New Central Library explains how these ideas have been incorporated into its design. This transparent approach supports the Council’s accountability to the people of Christchurch.

4. Roles and responsibilities

Why are clear roles and responsibilities important?

4.1

Good governance gives direction and surety to the people who put ideas into action and bring projects to life. The people at each level of project governance need to understand what part they play in completing the project and delivering intended outcomes.

4.2

Clearly documented roles and responsibilities confirm what is expected from each position and group, and how they work together. When roles and responsibilities are well understood – and followed – it helps each person make their intended contribution. If roles and responsibilities are not well understood, these contributions might be duplicated or, worse, not made at all.

4.3

Having clear roles and responsibilities also supports good decision-making when different views or conflicts need to be resolved.

Project Control Group roles and responsibilities were not well defined

December 2014

4.4

In December 2014, the terms of reference for the New Central Library Project Control Group were not fit for purpose. They were based on a CERA template, which the Council had not amended for this project.

4.5

The template was based on the structure that CERA uses for its anchor projects. This has a Project Control Group in a management role, with governance provided by a Project Steering Group. According to the terms of reference, the Project Control Group supports the Project Steering Group. This did not match the New Central Library structure, which only had a Project Control Group.

4.6

Some Project Control Group members were not aware that there are terms of reference. Also, some members did not fully understand their roles and responsibilities in the group.

4.7

Roles and responsibilities for the Project Control Group are included in the business case and also in the project management plan. However, these lacked the detail we expected. There was more detail about individual roles than group roles.

4.8

We expected to see roles and responsibilities for each part of the governance structure clearly documented. For example, we expected to see details of membership, who the chairperson is, when and where meetings will be held, and what the information and reporting requirements are.

4.9

The project team’s diagrams of the governance structure for the project did not reflect the actual structure that was in place. This was not explained. For example, the business case explains that governance is designed to remain above the Project Control Group, but the accompanying diagrams show the Project Control Group having a governance role. Several people also told us that the Project Control Group provided governance for the project.

October 2015

4.10

In October 2015, the Council has produced new terms of reference that provide a much better description of the Project Steering Group’s roles and responsibilities. They have been written specifically for the New Central Library Project Steering Group, which makes them more fit for purpose.

4.11

The terms of reference include the type of information we expected to see: a clear purpose for the group and its specific responsibilities, the role of the group as a whole, and what is expected of individual members of the group. The terms of reference also include more administrative matters such as membership of the group and requirements for papers and meetings and for out-of-session decisions.

4.12

The Project Steering Group accepted the new terms of reference at its first meeting in August 2015.

Other parts of the governance and management structure were not well identified, and those roles were also unclear

December 2014

4.13

In December 2014, the Council had not clearly identified how other individuals and groups provided management or governance oversight of the project. Some people in important management positions, including the chief executive, as well as groups that are part of the Council’s internal management structure, were expected to provide oversight of the project as part of their day-to-day roles. Project documents mentioned only some of these people, and their exact roles in governing or managing this project were not included.

4.14

We expected project documents to clearly identify people and groups with a governance or management role, explain what their roles and responsibilities were, and show how they related to each other. If it is not clear who is responsible for providing governance or management, there is a risk that oversight of the project does not happen.

October 2015

4.15

In October 2015, the new terms of reference cover the Project Steering Group only and do not include an explanation of how other parts of the Council provide governance to the project. Some people we spoke to, especially those who are part of other management groups within the Council, had a good understanding of the role other groups have in governing the project. In our view, it would be beneficial for the project documents to clarify the role of different groups and how they fit together, including a diagram of the governance structure.

5. Leadership

Why is leadership important?

5.1

Effective leaders model behaviours and actions that promote expectations of high standards of performance, professional conduct, and achievement. They show this in many ways, including:

- scrutinising and challenging proposals to inform and make good decisions;

- owning those decisions and being ready for scrutiny;

- ensuring clear and open communication within and outside the project;

- complying with relevant legislation and other requirements; and

- promoting a culture that commits to learning and continuous improvement.

5.2

Leadership is critical to a project from its early stages through to its outcomes. Poorly led projects can be managed to specifications but might compromise wider outcomes.

5.3

Good leaders can also identify opportunities from adversity. If their strategic views and insights are lacking, the project might miss opportunities for new and innovative approaches to achieving the outcomes.

The Project Control Group has made progress

5.4

Members of the Project Control Group showed commitment and enthusiasm for the project. The Project Control Group led the project to complete a business case and concept design. Based on these documents, councillors agreed in March 2015 that the project was ready to approach the market for expressions of interest. This was an important step in achieving the project’s goals.

Neither the Project Control Group nor anyone else was providing leadership at the level we expected

December 2014

5.5

In December 2014, the Project Control Group was not providing the type of leadership we expected to see as part of effective governance. In our view, the Project Control Group was operating as a management group. We expected to see leadership at a governance level that was driving the project towards achieving its outcomes but also challenging what those outcomes are and the best way of achieving them. We also expected to see leadership in striving for best practice and looking for ways to improve.

5.6

Without strong leadership, projects are at increased risk of exceeding their budget and timeline and not meeting their stated objectives. For this project, there is also the risk that the project will fail to deliver the right library for Christchurch that fits in with other parts of the Canterbury rebuild and other Council activities.

October 2015

5.7

The new Project Steering Group has only been in place since August 2015. When we visited in October 2015, it had held only two meetings. Therefore, the group has had limited opportunity to demonstrate its leadership of the project.

5.8

However, its members are more senior and experienced than members of the Project Control Group. They are better placed to provide oversight at the right level. When we spoke to them, they had a good understanding of the main project risks and issues, and where leadership was needed to address these.

5.9

People also spoke positively about the new independent chairperson and were confident he has the right attributes to bring the leadership needed.

5.10

Below the level of the Project Steering Group, the project’s development director has also shown effective leadership. He has led the design and implementation of the improvements to the project’s governance arrangements. He has also led the project through several steps to address its main risks and issues. These are described in more detail in paragraphs 5.23-5.26 and paragraph 5.34.

5.11

Based on current timelines, the project still has nearly three years left before the New Central Library opens to the public. Strong leadership during that period will be critical to ensuring that the project achieves its objectives. In our view, the new governance arrangements are now much better placed to provide the leadership required.

Risk management could be improved

December 2014

5.12

In December 2014, we identified weaknesses with the way that risks were being reported, monitored, and mitigated. According to the Project Management Plan, the Project Manager was responsible for maintaining the risk register. However, no-one was clearly identified as responsible for risk management.

5.13

We expected the Project Control Group to take the lead in managing risks, but we did not see evidence of this. Risks were not an agenda item for the Project Control Group, and minutes mentioned only some specific risks. The Project Manager’s monthly report to the Project Control Group had a section on risk, but this mentioned only a few risks. It did not include a risk register or any detail about risks.

5.14

The risk register for the project included risks down to a low level. The version we saw listed 171 different risks. Seventy of these were rated as a high risk. Using the risk register, we found it difficult to identify the project’s biggest risks.

5.15

The register also lacked detail about who owns each risk and what mitigation has been identified. We expected to see the full risk register condensed into a smaller document that clearly identified the main risks with detail about who owns the risk and what action was being taken to mitigate the risk. This information should have been provided to the Project Control Group.

October 2015

5.16

In October 2015, the risk register was more focused. The latest version lists only the 20 most important risks and provides more information about each risk and the mitigation approach adopted. It is easy to see what the main risks are and what is being done about them.

5.17

The risk register forms part of the regular reporting to the Project Steering Group and is discussed at its meetings. We found people on the Project Steering Group had a good understanding of the risks and are therefore in a much better position to address them.

Risks of affordability and funding

5.18

During our audit in December 2014, we identified two significant risks that, in our view, needed stronger leadership. These were risks of affordability and funding. When we spoke to them, Project Control Group members were not as concerned about these risks as we would have expected and were taking little action to mitigate them.

5.19

These risks are still present, but the Council has since taken a number of steps to address those risks. In paragraphs 5.20-5.35, we describe the two risks, what we found in December 2014, and what the Council has done about them since then.

Leadership was not shown towards risks of affordability

5.20

In our view, the Project Control Group showed poor leadership towards the project’s affordability. The Project Control Group focused on making the library as big as possible without enough consideration of the budget available.

5.21

In our interviews, we were told that the concept design had been significantly over budget. Project reporting confirms this. Project reports also show that the Project Control Group dismissed smaller and cheaper options and simply accepted that cost was a risk.

5.22

It was not until December 2014, when the Council’s senior management made it clear that councillors would be very unlikely to increase funding for this project that anything was done to try and reduce costs. Project reports confirm that the Project Control Group would still not compromise on floor space and had to look for other approaches.

5.23

Led by the Development Director, the project team reviewed and analysed the cost for each subsection of the proposed design and compared the cost breakdown to other similar projects. This analysis identified parts of the project where costs could be reduced without affecting outcomes. As a result, the project team was able to bring the expected cost within the budget of $85 million. Project reports show that most of these savings were in the groundwork and foundations ($5 million) and project management ($5.5 million).

5.24

The project team also commissioned a detailed risk assessment of the cost breakdown to provide assurance to councillors that the expected cost was realistic and achievable before councillors were asked to approve the concept design.

5.25

The assessment worked out the probabilities of different cost scenarios for each subsection of the project and then used this information to calculate the likely range of total project costs. The results of the assessment confirmed that the revised design had an expected cost of $85 million. This included an allowance of $16 million for contingencies and cost escalation. Councillors approved the concept design on this basis on 26 March 2015.

5.26

As the design became more developed, the cost estimates increased again to $99 million. The project tender process was put on hold so that the Council could complete a value management exercise and again identify where savings could be found. This exercise found some savings within the design. However, to bring the costs down to $85 million, the floor space needed to be reduced by 300 square metres.

5.27

The Council’s Libraries and Information Unit was opposed to reducing floor space, and the matter was raised to the newly formed Project Steering Group. After considering all viewpoints, the Project Steering Group endorsed the proposal to reduce floor space.

5.28

The project’s independent quantity surveyor was then able to certify that the cost estimate for the design was achievable within budget. This allowed the Council to issue its request for proposal to three shortlisted tenderers.

5.29

The value management exercise caused a delay of six weeks. However, it provides an example of how the new governance arrangements have shown leadership in managing conflicting views and resolving an issue that could have caused the project to fail.

Leadership was not shown towards funding

5.30

We also saw a lack of leadership towards philanthropic funding. Under the Cost Sharing Agreement, $10 million of the funding for the library should come from a philanthropic source. The Cost Sharing Agreement does not specify where this funding will come from or who is responsible for finding donors. However, representatives from CERA and the Council told us that CERA had accepted responsibility for sourcing this funding.

5.31

Project records show that, in September 2013, CERA advised the Council that it could not guarantee any philanthropic funding. The project noted this as a risk but progressed under the assumption that $10 million would be found. Project Control Group minutes over several months show that the Project Control Group took a “hands off” approach and simply identified it as a risk. The Project Control Group did not identify any alternative strategies for raising the money some other way or for cutting costs from its chosen design.

5.32

More than a year later, CERA had not made any progress in raising funds. As a result, when the project team asked the councillors to approve the concept design on 26 March 2015, $10 million of the $85 million budget was still at risk.

5.33

At their meeting on 26 March 2015, councillors questioned the project team about affordability risks. Councillors were clear that they were not prepared to underwrite the extra $10 million. Councillors asked the project team to report back in September 2015 with an update on project funding, including the $10 million in philanthropic funding.

5.34

Since then, the Council has taken some initial steps to try to raise the required funds. The Council has engaged a consultant who specialises in raising funds for projects to build community facilities. The consultant has developed a strategy for raising the funding required. This strategy was presented to the councillors in September 2015.

5.35

Councillors endorsed the consultant’s recommendations, including to set up a fundraising steering group comprising the mayor, other councillors, and community members. The Council has also started to identify other options in case the philanthropic funds are not forthcoming.

5.36

It is too early to say whether the Council will be able to raise all or some of the required funds, but the Council taking more responsibility for this is a positive step. The lack of philanthropic funding is still a risk for the project, but it is clearly recorded as such and people at all levels are well informed about the risks and the steps in place to address them.

The project would benefit from independent assurance and review

5.37

When we spoke to members of the Project Control Group, we found some awareness of good governance and project management practice. Some members were looking at ways to improve governance of the project. However, this was not widespread. We note that there is no Independent Quality Assurance (IQA) over the project. IQA reviews are generally considered good practice because it can provide independent assurance that the project’s structures and processes support successful delivery of the project. We think that the Council would benefit from this type of independent review.

6. Information and reporting

Why are information and reporting important?

6.1

People leading projects must balance limited resources with direction and decisions that have the best possible influence on achieving outcomes. They need to make sensible choices based on what they can know now and what influence each choice will have. They must understand the current state of the project, the decisions needed, and the effects of their choices.

6.2

Project leaders are usually kept informed through regular reporting of present and future-focused information, including:

- current project performance, such as milestones, activities, achievements, work in progress, resource capacity, and health; and

- anticipated events in the future, such as potential risks, ongoing issues, and resource demands.

6.3

Information should be tailored to meet the needs of decision-makers. It should be accurate, relevant to their role, and presented in a way they can readily understand. Too much information can obscure what they need to know.

6.4

Decision-makers must also make sure that the people who will act on their decisions know what those decisions are so they can put them into practice.

Project Control Group members are well informed about the project

December 2014

6.5

In December 2014, members of the Project Control Group got regular reporting of important project information that allowed them to monitor progress and make decisions. In our interviews with Project Control Group members, they told us they were satisfied with the information they received and that it was accessible, timely, and relevant. We found that they were well informed about the project.

6.6

The Project Management Plan for the New Central Library put the onus on individuals to make sure they have the information they need. The Plan also included responsibilities and information channels to support information getting to the right people. These included detailed distribution lists.

6.7

Members of the Project Control Group also told us they acted as intermediaries between the project and other specific parts of the Council. For example, the Libraries and Information Unit representative shared information between the project and the Libraries and Information Unit.

6.8

We identified a few improvements that could be made. For example, project reporting would benefit from adding visual aids, such as a dashboard, to give an overview of the project’s status. (We identify other improvements that could be made to reporting project risks in section 5.)

October 2015

6.9

In October 2015, project reporting has been improved. Papers to the Project Steering Group include a dashboard-style report that highlights important information about budget, risks, issues, and milestones. Papers also include an overview of the project’s status and clearly identify matters for discussion. We spoke to members of the new Project Steering Group and found that they were well informed about the project and satisfied with the information and reporting they receive.

6.10

The Council has appointed an external company to provide project management services to the project. This includes a monthly financial report and the risk register. These also form part of the papers for the monthly Project Steering Group meetings. The external project managers also provide reporting to the Project Control Group.

6.11

The Council has used experts to get better information about the project. For example, the Council used consultants to carry out financial modelling of funding options and to complete a risk analysis of the project’s affordability. This information gave councillors more confidence in the decisions they made about the project.

Project Control Group minutes could be improved

December 2014

6.12

In December 2014, Project Control Group minutes could have been improved in several ways. Minutes of meetings should allow someone who was not at the meeting to follow the main discussion points, see what decisions were made, and see any action points created. Project Control Group minutes did not meet this requirement. They could have been improved by:

- adding the main points made in discussions;

- separating the record of the current meeting from earlier meetings;

- clearly highlighting decisions; and

- clearly identifying action points and who they have been assigned to. They should also include a clear record to show the status of action points.

October 2015

6.13

When we visited the Council in October 2015, there had only been one meeting of the new Project Steering Group. We attended the second meeting. Therefore, there was only one set of minutes for us to review. These minutes clearly showed the topics that had been discussed at the first meeting and, where applicable, recorded what decisions the Project Steering Group made.

Programme-level reporting

December 2014

6.14

In 2014, groups operating at a programme level, both within the Council and the Central City Programme Steering Group, received regular information about the project. Internally, there was good communication between people in the Project Control Group and other parts of the Council.

6.15

The Central City Programme Steering Group was also getting regular information about the project. Two members of the Council’s leadership team are members of the Central City Programme Steering Group, and the Council provides a monthly report on the project. Information is also shared through CERA’s representative on the Project Control Group.

6.16

However, we found some information in reports from the project to programme-level groups that could be misleading. For example, the March 2015 report to the Central City Programme Steering Group shows the overall project status as “green – on track” but most underlying areas are “amber – at risk”. One area is “red – critical”. In the Project Status Report for September 2014, the overall status is green but several underlying areas are rated red. It is important that reports provide a realistic view of how risks could affect the project.

October 2015

6.17

In October 2015, programme-level reporting now provides a more balanced view of the overall project status and what the main risks are. In the reports we saw, summary indicators now reflect underlying information more accurately. People operating at a programme level will now have more reliable information about this project.

7. Capability and participation

Why are capability and participation important?

7.1

People governing projects require a wide set of attributes and knowledge to be fully effective. They are more likely to achieve successful outcomes when they have the right qualities, skills, and experience to help them make good decisions and judgements.

7.2

These people need to bring their expertise and background to the project. They also need to commit to, and take part in, the project and any wider programmes the project is part of.

7.3

Balance and scale are also important. Different and complementary experiences and skills bring a breadth of knowledge. This should include the right amount of independence to bring an unbiased perspective. There also needs to be a mix of views to stimulate challenge and debate. Robust discussion enhances the effect the group can have. This mix adds up to more than the sum of the separate parts.

7.4

Group size should optimise opportunities for good debate and consensus without becoming a wider forum for every project aspect.

Most major stakeholders are represented on the Project Control Group

7.5

The Project Control Group had members representing most major stakeholders in the project. These members were the Libraries Manager (who is also the project sponsor), a representative from Library Services, the Project Manager, the Unit Manager for Anchor Projects, and a representative from CERA.

7.6

CERA was represented on the Project Control Group to support and enable CERA’s role in this project as well as its wider co-ordination role for the rebuild. We found that CERA’s representative was well placed to fulfil this role.

The Project Control Group lacked governance capability

December 2014

7.7

In December 2014, not all members of the Project Control Group had experience of a project of this size and significance. The project is also taking place in a complex political environment with significant central government involvement that is unusual for some of the people involved with this project.

7.8

In our view, one of the reasons that the Project Control Group acted as a management group was because some of its members lacked the skills and experience to provide effective governance. This view was based on our interviews with Project Control Group members, which identified their level of understanding of issues and how they could be resolved.

7.9

The Project Control Group did not have a designated chairperson. A strong chairperson helps run meetings effectively. The chairperson ensures that discussions remain focused and lead to good decisions. The chairperson also ensures that all views are heard and processes are followed.

October 2015

7.10

In October 2015, governance is provided by the new Project Steering Group. The Council members of the new Project Steering Group are the Finance Manager, the Anchor Projects Unit Manager, and the General Manager for Culture, Leisure and Parks. These people are in positions where they can make sure the New Central Library project is consistent with the Council’s long-term plan and annual plan.

7.11

The Development Director and the Libraries Unit Manager, who is also the project sponsor, attend the Project Steering Group meetings as well. The Project Steering Group also has an external independent chairperson.

7.12

The Council has also changed the Project Control Group membership to bring a stronger balance of management experience and leadership skills.

The Project Control Group lacked independence

December 2014

7.13

In December 2014, there were no independent members on the Project Control Group or within the rest of the project’s governance and management structure. Independent members can strengthen governance and management by bringing more experience and providing perspective, real challenge, and alternative views. We saw independent chairpersons from outside the organisation make a positive difference to the other two projects we looked at.

October 2015

7.14

In October 2015, the external chairperson of the new Project Steering Group brings independence to the project’s governance. He also brings experience in local government, major construction projects, and governance. These are all of value to the project.

7.15

Other members of the Project Steering Group told us they had already seen the benefits of his independence in the way he managed the recommendation to reduce floor area at the Project Steering Group’s first meeting. He was able to get agreement even when there was strong opposition.

Getting Ngāi Tahu involvement has been difficult

December 2014

7.16

In December 2014, there were difficulties getting Ngāi Tahu2 involved with the project. Ngāi Tahu told us it had not been able to commit resources to the project because its own resources were stretched across all the development taking place in Christchurch.

7.17

The Christchurch Central Recovery Plan identified Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu as a partner in the project. The business case mentions that the project team engaged with Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tuāhuriri3 early on to get their input into the concept design.

7.18

The iwi identified values they would like to see in the design and other ways of incorporating Māori design elements and artwork. Since then, Ngāi Tahu told us it has not had enough resources to be as involved as it would like with this project. Project documents recognised this as a reputational risk.

October 2015

7.19

The Council told us it has re-engaged with Ngāi Tuāhuriri through the Matapopore Trust, which is now providing some input to the library design and to some potential artwork. The Council is also considering whether it can involve Ngāi Tuāhuriri in the project governance arrangements.

8. Our recommendations

8.1

We recommend that Christchurch City Council:

- continue to strengthen the new governance arrangements that are in place for the New Central Library project by:

- clarifying project accountabilities at all levels; and

- reviewing the new governance arrangements on a regular basis to make sure they are bringing the improvements to governance that were intended; and

- review and strengthen its quality assurance processes for its major capital projects, including the New Central Library.

1: See “Public Accountability and holding to Account” on the Centre for Public Accountability site: www.centreforpublicaccountability.org, accessed 6 April 2015.

2: Ngāi Tahu is the iwi of the Southern region of New Zealand.

3: Ngāi Tuāhuriri is the hapū with mana whenua over Christchurch City.