Acute Services Building

1. Introduction

1.1

The theme for our work programme in 2014/15 was Governance and accountability. We chose this theme because of recent significant changes in legislation and financial reporting standards that affect public sector accountability arrangements. Good governance is important for achieving successful outcomes for major projects.

1.2

We audited three projects that are part of the Canterbury earthquake recovery. The recovery has long-term implications for people’s lives as well as the economy. Rebuilding Canterbury is a priority for the Government and is a significant area of public spending. Strong governance is needed to ensure that public funds are being spent appropriately, that entities are working together to deliver intended outcomes, and to provide clear accountability for Cantabrians and all New Zealanders.

1.3

The three projects we audited were the Bus Interchange, the New Central Library, and the Acute Services Building at Christchurch Hospital. This document reports our findings and conclusions for the Acute Services Building.

1.4

We have assessed the governance and accountability arrangements of the three projects against six principles of good governance. We identified these principles by drawing on some of our previous reports as well as other relevant literature. Figure 1 sets out the six principles.

Figure 1

Principles of good governance

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Clarity of purpose | Governance sets a clear strategic purpose for the entity or project and provides direction that drives the entity towards achieving that purpose. |

| Accountability | The governance structure includes a clear accountability framework. |

| Roles and responsibilities | Each part of the governance structure has clear roles and responsibilities that are complementary and aligned with strategy. |

| Leadership | Leadership is demonstrated across all levels of governance. |

| Information and reporting | The governance arrangements are supported by information and reporting for monitoring performance, managing risks, making decisions, and providing direction. |

| Capability and Participation | The right people are involved in governance. |

Governance arrangements for the Acute Services Building project

Background

1.5

The Acute Services Building project is part of a $650 million programme of work that also includes a major redevelopment at Burwood Hospital. The work at Burwood Hospital is being done before the Acute Services Building project and is expected to be completed in 2016. The governance arrangements for the Acute Services Building project also apply to the work at Burwood Hospital.

1.6

Our audit focused only on the Acute Services Building project. However, where it makes sense to consider both projects, we refer to the Burwood Hospital project as well.

1.7

Canterbury District Health Board (the DHB) had already produced a business case for redeveloping the facilities at Burwood Hospital and Christchurch Hospital before the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011.

1.8

After the earthquakes, there was a lot of damage to the DHB’s facilities. Also, many of its remaining hospital beds were at risk of damage from subsequent earthquakes. There was also a risk that engineering reports could find them unsafe. This meant that there was some urgency to start building new facilities.

1.9

Usually, district health boards run their own major construction projects and put their own governance arrangements in place. The Ministry of Health (the Ministry) monitors the project and advises Cabinet on any important decisions.

1.10

With this project, the Government said it was concerned that the DHB was under a lot of pressure continuing to provide day-to-day health services at the same time as managing its own recovery from the earthquakes. Therefore, the Government decided that it would relieve the pressure on the DHB and bring in expertise that could help build some of the new facilities quickly by introducing new arrangements for the DHB’s facilities redevelopment.

New arrangements

1.11

For our audit, we did not look at whether the new arrangements should have been introduced or whether they are better than alternative arrangements, including the previous arrangements. We looked at the way the new arrangements were implemented and how they are working. Paragraphs 1.12-1.21 describe the new arrangements.

1.12

Under the new arrangements, the Ministry is responsible for managing the project and holds the legal authority for any contracts. This was a new role for the Ministry, which is using a mix of existing staff and external contractors to manage the project.

1.13 The then Minister of Health appointed a new group, the Hospital Redevelopment Partnership Group (the HRPG), to provide governance for the project. The HRPG has four full members. Three are independent of the project and between them they bring a mix of experience of major construction projects and healthcare. The fourth member is the chairperson of the DHB. The HRPG also includes people who represent the Ministry, the DHB, and the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA).

1.14

Our findings focus on the HRPG because it is the main group providing governance to the project. Where appropriate, we also refer to other entities, groups, and people that are part of the project’s wider governance and accountability framework.

1.15

The role of the DHB under the new arrangements is less clear. Cabinet gave the DHB some specific tasks that relate to the DHB’s transition to the new facilities. These were to prepare a workforce transformation plan and an Information, Communication, and Technology plan.

1.16

Cabinet did not give any further indication about how it intended the DHB would be involved on a day-to-day basis – for example, how the DHB would provide input into the design process or other decisions that might affect the DHB’s delivery of health services.

1.17

We understand that the DHB was not consulted on the new arrangements. No-one we spoke to was able to tell us what the DHB’s role was or how the DHB, as the end user and owner of the completed facilities, was supposed to provide input. This is not satisfactory.

1.18

The new arrangements were introduced quickly because of the urgent need to build new facilities. However, this meant that there was little time to plan how the arrangements would work. As a result, the arrangements were not clear in several areas – in particular, accountabilities for the project, roles and responsibilities of the entities involved, and how information would be shared. We discuss these further in sections 3, 4, and 6.

1.19

The new governance arrangements are similar to those used in other parts of the public sector. For example, the Ministry of Defence leads the procurement of major defence capabilities on behalf of the New Zealand Defence Force. We expected to see that the Ministry had looked at how similar arrangements work in other sectors to help it set up the new arrangements in Canterbury. However, we did not see any evidence of this.

1.20

The Government has now introduced similar management and governance arrangements for other major construction projects in the health sector, in Dunedin and the West Coast. The Ministry told us that it expects the new model to become the norm for major health capital projects. Any lessons that can be learned from this project will have wider implications than just for the programme of work in Canterbury.

1.21

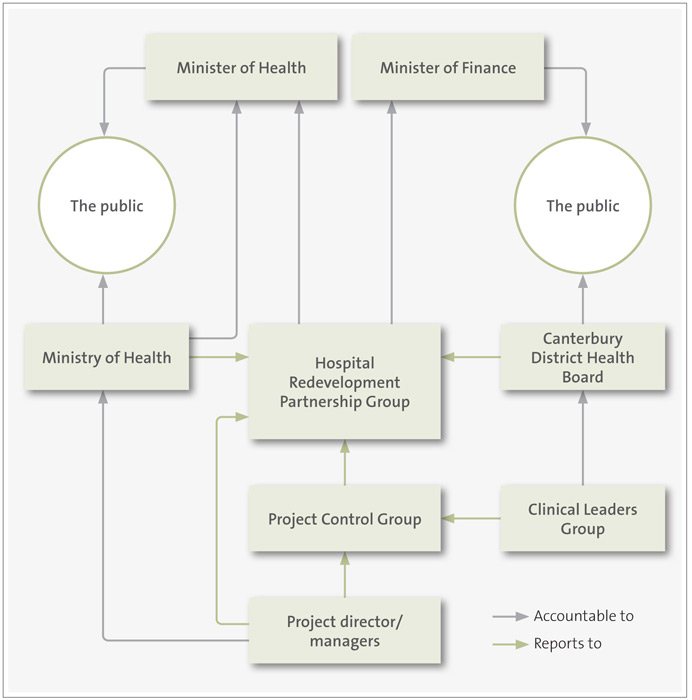

Figure 2 shows our understanding of the governance structure for the project. Our interpretation is based on information we gathered from interviews and reviews of documents.

Figure 2

Acute Services Building project governance structure

Source: Office of the Auditor-General

*The DHB is generally accountable to the Minister of Health. However, for this project, the DHB’s accountabilities are unclear. This is explained further in section 3.

Overall findings

1.22

We found mixed results for the Acute Services Building project. The HRPG has brought strong leadership to the project, which has made good progress as a result. The project is now in negotiations with its preferred contractor for the main construction contract. The HRPG is supported by both the main partners – the Ministry and the DHB – despite their conflicting views on many parts of the project.

1.23

However, strong leadership was needed to compensate for a lack of clarity about the arrangements. In particular, the roles and responsibilities of the main partners were unclear and not well documented. In addition, we found confusion about who is accountable for the project. People we spoke to could not give us clear and consistent explanations about roles and accountabilities.

1.24

Given that this project has a new governance model, clarity around accountabilities, roles, and responsibilities is particularly important. Clearer roles and responsibilities could also provide a framework for resolving disagreements between the partners.

1.25

We note that the Ministry has identified a programme of work to strengthen the governance arrangements for this project that addresses some of the findings from our audit.

2. Clarity of purpose

Why is clarity of purpose important?

2.1

People that set the direction for projects need to clearly understand the project’s purpose, including the limits to what they have to do and the project’s intended outcomes. They must also be able to understand the influence of their decisions and actions. If they do, goals are more likely to be met and intended outcomes achieved.

2.2

Individually and together, people in governance positions need to focus on more than just the reports on the project. They need to think at a strategic level, disseminate that thinking and understand the effects of their direction.

The HRPG has a clear purpose

2.3

The HRPG’s purpose is clear and well understood by its members. The HRPG’s members were initially appointed in September 2012 to develop a final business case and fast track the design of the Burwood Hospital redevelopment. The initial terms of reference sent to each member of the HRPG confirm this purpose.

2.4

Once the final business case was approved, there was a clear purpose for constructing the Acute Services Building. Members of the HRPG we spoke to clearly understood that they were there to oversee delivery of the best possible facility on time and within budget, in keeping with the business case.

2.5

However, there has been some disagreement over the scope of the business case and what the approved funding covers.

The HRPG’s scope has been extended over time

2.6

The HRPG’s members were initially appointed for a fixed term ending on 31 May 2013. Cabinet had not decided on the final governance arrangements and intended to review the arrangements when the business case was approved.

2.7

When Cabinet approved the detailed business case in March 2013, it tasked the HRPG with the next phase of the project, the design phase. Cabinet agreed to review the governance arrangements again when this phase was completed.

2.8

This pattern of tasking the HRPG one stage at a time has continued, and the HRPG is now working under the assumption it will oversee the remainder of the project. Cabinet has also expanded the HRPG’s scope. For example, in June 2014, Cabinet agreed that the HRPG would oversee the DHB’s Earthquake Repairs Programme.

3. Accountability

Why is accountability important?

3.1

Public accountability is how authorities using public resources explain their activities:

The level of citizen trust in the ability and motivation of decision-makers in authority determines how well society works. If decision-makers are required to explain their intentions, reasons and performance standards publicly, fully and fairly before they act, citizens can act fairly and sensibly to commend, alter or halt the intentions.1

3.2

Who is accountable for what, and who they are accountable to, needs to be clear. Everyone involved in the activity should understand the accountability framework.

3.3

When projects are funded by public money, the public has the right to know whether that money is well spent. If accountability is unclear, they cannot know who is ultimately responsible for the results.

3.4

Being accountable to the public means keeping the public informed about important decisions, how the project is progressing, and what results are being achieved. The public are often asked for their views about what they want from a project. Decision-makers should ensure that the public’s views are heard. Those decision-makers should then tell the public how they have acted on those views.

Accountabilities are confusing

3.5

There is no clear accountability framework, and no one person or group is accountable for the successful delivery of the project. We heard conflicting views about who is accountable for what and to whom. In our interviews, we found that some people thought that the HRPG is accountable for delivering the project on time and within budget. Other people thought that the Ministry is accountable.

3.6

Some specific accountabilities are defined. For example, according to its terms of reference, the HRPG is “accountable to the Ministers of Health and Finance for quality and timeliness of deliverables and effective fulfilling of responsibilities commissioned by Cabinet”. When we spoke to them, members of the HRPG had a good understanding of this accountability.

3.7

However, the HRPG’s accountability does not match its authority. In practice, the HRPG makes decisions and the Ministry acts on these. In theory, the HRPG does not have the authority to tell the Ministry how to act. It is not clear what would happen if the Ministry chose to act against a decision made by the HRPG.

3.8

We also found confusion about what the Ministry is accountable for. The Ministry holds the financial delegations for this project, but some people we spoke to confused this with accountability for delivering the project. The Ministry also has legal responsibility for project contracts. Project managers attend HRPG meetings to give an account of project progress and performance but are technically accountable to the Ministry.

3.9

The effect of the arrangements on the DHB’s accountabilities is also unclear. Under the previous governance model, the DHB would have been responsible for managing the project and accountable for its delivery. The Ministry would have had a monitoring and oversight role.

3.10

Once the project is finished, the DHB will have accountability as the owner and operator of the new facility. Until then, as we explained in section 1, the DHB’s role under the new arrangements is not clear. Some of the people from the DHB we spoke to told us they are uncertain about what effect, if any, the new arrangements have on the DHB’s accountability.

3.11

Final approval for major decisions, such as signing off the business case or committing funds, has not changed. These major decisions need to be cleared by the National Health Board’s Capital Investment Committee and then approved by Cabinet.

Information about the project is available to the public

3.12

Information about the project is made available to the public in several ways. Communication is a joint responsibility of the HRPG and the DHB. They work together to communicate project milestones.

3.13

On a day-to-day basis, the DHB provides detailed information through its website. The DHB also produces a regular newsletter, It’s all happening, which is available in print and on its website. The newsletter covers both the Burwood Hospital and the Acute Services Building projects.

3.14

The DHB also uses social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to provide information and answer questions from the public. These communications support the Ministry and the DHB’s accountability to the public.

4. Roles and responsibilities

Why are clear roles and responsibilities important?

4.1

Good governance gives direction and surety to the people who put ideas into action and bring projects to life. The people at each level of project governance need to understand what part they play in completing the project and delivering intended outcomes.

4.2

Clearly documented roles and responsibilities confirm what is expected from each position and group, and how they work together. When roles and responsibilities are well understood – and followed – it helps each person make their intended contribution. If roles and responsibilities are not well understood, these contributions might be duplicated or, worse, not made at all.

4.3

Having clear roles and responsibilities also supports good decision-making when different views or conflicts need to be resolved.

Roles and responsibilities are unclear

4.4

The roles and responsibilities of the three main partners – the HRPG, the Ministry, and the DHB – are unclear and not understood consistently by people involved in the project. Some people working in the project described it as if they have “two masters”, namely the Ministry and the DHB. There is no agreed process for reaching agreement on decisions or for resolving conflict between the Ministry and the DHB. When there have been disagreements it has taken time and effort to resolve them.

4.5

Some tension can be expected and may even be desirable. However, in our view, the level of tension for this project has created inefficiencies. A high level of tension can also be unpleasant and stressful for people working on the project.

4.6

Roles and responsibilities are not clearly documented. They are spread across several documents such as Cabinet minutes and different versions of the HRPG’s terms of reference. These documents lack detail, particularly about the roles and responsibilities of the Ministry and the DHB. For example, the latest version of the terms of reference for the HRPG states that:

…the HRPG will work with CDHB to ensure the CDHB has available and committed appropriate resource and expertise to facilitate prompt input in to HRPG considerations.

4.7

We are not aware of any supporting documents or process that provide more detail about how this requirement will be put into practice.

4.8

In our view, clearer roles and responsibilities would help the three partners work together more effectively and efficiently. Given that these are new arrangements that exist in an already complex environment, we expected the HRPG, the Ministry, and the DHB to work out clear roles and responsibilities when the arrangements were introduced. In particular, we expected them to look at how similar models work in other parts of the public sector.

4.9

Clearer roles and responsibilities could provide a structure to help resolve misunderstandings or disagreements. Roles and responsibilities should be comprehensive and be detailed enough to minimise any ambiguity or uncertainty.

People are making things work

4.10

Despite unclear roles and responsibilities, people are getting on with the project and doing their best to make progress. Project teams are working hard, and people have found ways of working together to make sure things get done. Everyone involved supports the HRPG and shares the goal of delivering a high-quality facility on time and within budget.

Responsibility for health and safety is unclear

4.11

Roles and responsibilities for co-ordinating health and safety between the hospital and the construction site were not well defined at the start of the project. Co-ordination has improved, but we consider that responsibilities should have been more clearly defined.

4.12

Health and safety is taken seriously, and all partners are aware of the risks of having a construction site adjacent to a hospital full of patients and staff. There is added complexity for this project because the construction site and hospital are managed by different entities.

4.13

Health and safety staff from the different entities meet weekly to share information. They have also introduced processes for the construction site to provide notice of any work that might affect the hospital.

4.14

However, some people we spoke to were not clear about health and safety responsibilities, particularly in an emergency. These people did not know critical information such as who to contact in an emergency. We understand that, since our audit, the Ministry and the DHB have aligned their emergency planning, including producing an emergency contact list.

Risk management

4.15

The HRPG’s role in managing project risks is not clear. We saw that the HRPG is managing risks effectively. However, it is unclear what the parameters are for escalating risks to the HRPG or what risk reporting is required.

4.16

This is another example where the documentation of roles and responsibilities lacks enough detail. A recent Gateway Review found that the risk management plan and risk reporting were not detailed enough for a project of this size and complexity. The Ministry has started to make some improvements in response to the Gateway review.

Responsibilities for managing interfaces are not well defined

4.17

Responsibilities for managing links with other projects were not well defined. The Acute Services Building project has close links with several other projects. These include the new Outpatients building, new car parking at the Hospital, the DHB’s Earthquake Repairs Programme, and the District Energy Scheme.

4.18

There are also links with the nearby Health Precinct. The Acute Services Building needs to co-ordinate with these other projects for both physical links, where work needs to match up, and critical timing issues – for example, where schedules need to match up. There can also be wider effects, such as congestion from several construction activities taking place in a small area. If interfaces are not managed well, there is a risk of work being delayed or rework being required.

4.19

At first, the HRPG did not have oversight of these other projects. The projects were being managed by the DHB, in some cases in partnership with other entities. People working on both the Acute Services Building and the other projects gave us examples of difficulties they had finding out what they needed to know to co-ordinate with each other. People were unclear about how issues might be resolved and did not know who was responsible for this.

4.20

Over time, Cabinet has expanded the HRPG’s scope so that it has oversight of these related projects. This should help with co-ordination. However, given that accountabilities, roles, and responsibilities were already unclear, there is the potential for even more confusion now that more projects are involved.

4.21

This makes it even more important that accountabilities, roles, and responsibilities for all the projects, both individually and as a whole, are clarified, documented, and communicated.

5. Leadership

Why is leadership important?

5.1

Effective leaders model behaviours and actions that promote expectations of high standards of performance, professional conduct, and achievement. They show this in many ways, including:

- scrutinising and challenging proposals to inform and make good decisions;

- owning those decisions and being ready for scrutiny;

- ensuring clear and open communication within and outside the project;

- complying with relevant legislation and other requirements; and

- promoting a culture that commits to learning and continuous improvement.

5.2

Leadership is critical to a project from early stages through to outcomes. Poorly led projects can be managed to specifications but might compromise wider outcomes.

5.3

Good leaders can also identify opportunities from adversity. If their strategic views and insights are lacking, the project might miss opportunities for new and innovative approaches to achieving the outcomes.

The HRPG has brought strong leadership to the project

5.4

The Ministry and the DHB agree that the HRPG has brought strong leadership to the project. All stakeholders speak highly of the HRPG and the results it is achieving. We were told that the HRPG is able to maintain a balance between acknowledging and challenging opposing views so that it can make decisions that move the project towards its goals. We saw evidence of this when we observed an HRPG meeting.

5.5

At the time of our audit, project progress was on track. Some milestones were forecast as being up to three months overdue, but the expected date for completion had not changed. The project will have more up to date information about whether its timeline is achievable once it finalises the main construction contract. However, we understand that the timeline is still acknowledged as a risk.

5.6

There was also a small forecast cost overrun. Project reports showed that the HRPG was actively managing this forecast overrun by identifying opportunities for savings and other funding sources.

There are significant risks in future phases of the project

5.7

The project will continue to need strong leadership through the tendering and construction phases. Although progress so far has been good, these phases bring significant risks that will need to be managed to achieve a successful outcome.

Construction costs may be higher than expected

5.8

When we did our audit, construction cost was recognised as the project’s biggest risk. The Canterbury recovery has generated a commercial construction market characterised by high and unpredictable costs. There is high demand for contractors but limited availability. A shortage of sub-trade availability adds to the risk. The main effect is on cost, but it could also have an effect on timing.

5.9

The HRPG and Ministry’s project team already experienced difficulty in securing contractors when they tendered for the main construction contract for the Burwood Hospital project in 2013. The Burwood Hospital project team told us that they found that tenderers were unfamiliar with the procurement type being offered. Tenderers responded by adding a premium to their pricing. Based on this, the Acute Services Building project team has used different tendering and contract structures to get the best result they can from the current market.

5.10

Now that the project has approached the market and is in negotiations with a preferred contractor, we understand there is now a much lower risk of construction costs being unaffordable.

Independent review of the project has been limited

5.11

The Acute Services Building project has not had the level of independent scrutiny we expected to see for a project like this. The DHB facilities redevelopment project is large and complex. The project also has a new set of governance arrangements.

5.12

We expected to see a range of independent reviews to provide assurance over the project’s governance and management processes and that the project is on track to deliver its intended outcomes. However, there have been only limited reviews of the project to date.

5.13

The project has had two Gateway reviews, the most recent in November 2014. Gateway reviews, at key points in a project’s lifecycle, are mandatory for a project like this. Gateway reviews provide a level of assurance that a project is progressing as expected and is on track to successfully deliver its outcomes.

5.14

The more recent Gateway review for this project had an “amber” rating. This means that the reviewers found that successful project delivery was feasible but that significant management issues would need to be resolved. The issues identified are consistent with the findings of our audit. We understand that the Ministry put in place changes to address the Gateway review’s recommendations.

5.15

The project has not yet procured an Independent Quality Assurance (IQA) review. An IQA review can provide assurance to those responsible for the project that the systems and processes in place are sound and will support the successful delivery of the project’s intended outcomes.

5.16

An IQA programme is often focused on project risks. For this project, we expected to see the HRPG and the Ministry, as the governors and managers of the project, assessing where assurance is needed and procuring a programme of IQA reviews accordingly. We understand that the HRPG and the Ministry are now making arrangements for an IQA review of the project.

5.17

As part of a programme of IQA reviews, we expected to see a review of how well the governance arrangements are working, with improvements made as applicable. As a project moves through different phases, it is good practice to review its governance arrangements to make sure they are appropriate for the stage of the project, the risks that exist, and any other influences on the project.

5.18

Given that the arrangements for this project are based on a new model, it is particularly important to review them to make sure they are working as intended and identify any areas where improvements are needed.

5.19

As described in this findings document, we found several areas where the governance arrangements could be improved – for example, clarifying accountabilities, roles, and responsibilities; having clear agreements for information sharing; and reducing the number of people who attend HRPG meetings.

5.20

Most people we spoke to about the project, including members of the HPRG, were aware that the arrangements could be improved. Despite this awareness, there has been not been any systematic attempt to review the arrangements and make improvements. Instead, we saw individual changes made when a specific need has come up.

5.21

The Ministry has also not commissioned any internal audit work for this project. The Ministry acknowledges that the Acute Services Building project is high risk. It is one of the Ministry’s top ten priorities. The Ministry could use internal audit work to help manage risks by providing visibility of, and assurance for, specific areas. We expected the Ministry to use its internal audit function to provide assurance over this project.

6. Information and reporting

Why are information and reporting important?

6.1

People leading projects must balance limited resources with direction and decisions that have the best possible influence on achieving outcomes. They need to make sensible choices based on what they can know now and what influence each choice will have. They must understand the current state of the project, the decisions needed, and the effects of their choices.

6.2

Project leaders are usually kept informed through regular reporting of present and future-focused information, including:

- current project performance, such as milestones, activities, achievements, work in progress, resource capacity, and health; and

- anticipated events in the future, such as potential risks, ongoing issues, and resource demands.

6.3

Information should be tailored to meet the needs of decision-makers. It should be accurate, relevant to their role, and presented in a way they can readily understand. Too much information can obscure what they need to know.

6.4

Decision-makers must also ensure that the people who will act on their decisions know what those decisions are so they can put them into practice.

The HRPG is well informed about project progress and issues

6.5

Members of the HRPG told us they are happy with the reporting they receive. Reports to the HRPG include crucial information such as cost, risks, issues, progress, and health and safety. These reports are comprehensive and of a high standard, but there are many of them. They are produced by different people and have an inconsistent format and level of detail. A consolidated report that brings all the reports together would be beneficial. This would give the HRPG a clearer overview.

There are no formal channels for sharing information from the HRPG

6.6 There is no formal process to ensure that people are informed about HRPG decisions and discussions. Instead, there is an assumption that people will share information with others who need to know it.

6.7

This means that sometimes people are not told about things when they should be. One example of this was when the HRPG and the Ministry asked Cabinet to increase the budget for Burwood Hospital from $190 million to $215 million. This has financial implications for the DHB, but it did not find out about this until later.

6.8

We were told that decisions are occasionally made outside of formal meetings, but there is no process for recording or communicating those decisions. We received a strong perception from our interviews with DHB staff that they are not well informed about decisions the HRPG makes outside of formal meetings.

6.9

We expected to see formal information channels built into the governance and management arrangements. This might include distribution lists for documents and decisions. If people are expected to act as intermediaries, this should be clearly documented as part of the project’s roles and responsibilities

There are no formal channels for sharing information between the Ministry and the DHB

6.10

We also found that people in the Ministry and in the DHB were not always getting the information they needed from each other. There has been disagreement about whether the information is needed and whether information requested has been provided. One example of this is information about how ownership of the new building will be transferred from the Ministry to the DHB when it is completed.

6.11

The Crown, through the Ministry, owns the Acute Services Building while it is being constructed. After completion, the building and related assets will transfer to the DHB. Details of the timing, mechanisms, and financial and practical implications of the transfer are only now being worked through.

6.12

Our understanding is that the DHB has been trying to resolve this with the Ministry for some time. The Ministry engaged with the DHB on this matter only recently. This delay has caused uncertainty for the DHB’s financial planning.

6.13

Without formal channels, some people have started to find ways to share information – for example, by setting up regular meetings. This has helped to build trust and has been largely effective in keeping people informed. Sometimes, there can still be delays in people getting the information they need.

6.14

Information sharing is another example of roles and responsibilities lacking clarity. Clear processes and agreements about what information needs to be shared, who should provide it, when it should be provided, and what format it should be provided in would help to reduce frustration and delays.

6.15

The Ministry will also need to share information with other district health boards in future projects that use this governance model. Introducing clear roles and responsibilities for information sharing at the start of a project will help it to run smoothly.

7. Capability and participation

Why are capability and participation important?

7.1

People governing projects require a wide set of attributes and knowledge to be fully effective. They are more likely to achieve successful outcomes when they have the right qualities, skills, and experience to help them make good decisions and judgements.

7.2

These people need to bring their expertise and background to the project. They also need to commit to, and take part in, the project and any wider programmes the project is part of.

7.3

Balance and scale are also important. Different and complementary experiences and skills bring a breadth of knowledge. This should include the right amount of independence to bring an unbiased perspective. There also needs to be a mix of views to stimulate challenge and debate. Robust discussion enhances the effect the group can have. This mix adds up to more than the sum of the separate parts.

7.4

Group size should optimise opportunities for good debate and consensus without becoming a wider forum for every aspect of the project.

The HRPG’s members bring independence and a good mix of skills to the project

7.5

The HRPG’s members have brought relevant skills and experience to the project. Their skills include construction knowledge and clinical expertise. They are also experienced in governance. The other partners in the project spoke positively about the HRPG. In particular, the chairperson of the HRPG is widely viewed as being very effective in this role.

7.6

Three of the HRPG’s members are also independent of the project. Their independence has strengthened governance by providing perspective, real challenge, and alternative views. This in turn has added robustness and transparency to decision-making.

7.7

Some people thought that the HRPG could benefit from an additional member. This was mostly because the existing membership was stretched when there were absences. The terms of reference allow for the Minister of Health to appoint another member.

Stakeholders are represented

7.8

The Ministry and the DHB are represented on the HRPG. The chairperson of the DHB is a member of the HRPG. The HRPG terms of reference also state that the HRPG will have “ex officio” members from the Ministry and the DHB. These two positions are filled by the Director of the National Health Board and the Chief Executive of the DHB.

7.9

The status of these ex officio members is not clear. The HRPG’s terms of reference suggest ex officio members have a different status to the other “ordinary” members but do not explain what this difference means.

7.10

The term “ex officio” usually refers to someone who has the right to membership of a group or board because of a position they hold. The HRPG’s ex officio members attend and speak at HRPG meetings but do not have voting rights. We have not seen any evidence to confirm that this was the intention for ex officio members of the HRPG.

7.11

Clinical staff are also represented indirectly. The DHB set up a Clinical Leaders Group to provide clinical input to the project. This group does not have a formal status, but it signs off on any decisions that have a clinical effect before those decisions go to the HRPG. The Clinical Leaders Group’s chairperson attends most HRPG meetings. These arrangements ensure that the HRPG is well informed about clinicians’ viewpoints.

7.12

CERA is also represented on the HRPG by an ex officio member. CERA’s representative did not attend any HRPG meetings between August 2014 and March 2015. This means that the HRPG might be making decisions without being fully informed about wider rebuild issues.

7.13

However, there are other communication channels with CERA, and CERA is well informed about the project. The Ministry also attends the Canterbury commercial support group led by CERA and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. This group shares information and lessons about the current construction market in Canterbury.

Too many people attend HRPG meetings

7.14

There are often too many people at HRPG meetings. Minutes show that sometimes more than 20 people attended a meeting. As well as the HRPG, attendees include project team members and advisors for both the Burwood Hospital and the Acute Services Building projects. Also, there are representatives from the Ministry and the DHB. Some of those people need to be there. Some come to only part of the meetings.

7.15

When there are too many people, good discussion can be limited, especially if lots of people want to speak. It can also be difficult to hear everyone in a large group. We saw this happening when we observed an HRPG meeting. We consider that the HRPG could be more directive about who attends the meetings. We understand that the HRPG has now started to limit the number of people at its meetings.

The Ministry was not well set up to deliver its new role

7.16

The Ministry did not initially have the capability or capacity for its role in this project. When the governance model was introduced, the Ministry was given the task of managing the project and supporting the HRPG. The Ministry did not have time to prepare for its new role because it was introduced suddenly and with little planning. The Ministry explained to us that this was a completely new function for it, and it did not have the people and processes in place for this role.

7.17

Over time, the Ministry has hired contractors to manage the project. The Ministry has also set up an internal group to help advise the Director-General of Health and keep him informed of project issues and risks. On the whole, these arrangements are now adequate for this project.

7.18

However, if the arrangements used for this project are used for other rebuild projects, the Ministry will need additional capacity for this role. If the Ministry is to become a centre of expertise for this type of project, we expect the Ministry to build up its capability in managing large hospital construction projects.

8. Our recommendations

8.1

We recommend that the Hospital Redevelopment Partnership Group (the HRPG), the Ministry of Health (the Ministry), and Canterbury District Health Board (the DHB) work together to agree and clearly document their roles and responsibilities and the lines of accountability. This should include learning from other parts of the public sector that use similar governance models.

8.2

We recommend that the Ministry and the DHB continue to work together to finalise arrangements for transferring ownership of the Acute Services Building and related assets from the Ministry to the DHB.

8.3

We recommend that the Ministry and the HRPG review and strengthen the quality assurance processes for the Acute Services Building project.

8.4

We recommend that the Ministry:

- develop standard processes and guidelines for how the Ministry and district health boards should work together in projects that use the same governance model as the Acute Services Building project; and

- increase its capacity and capability for the major health capital projects it is required to manage.

1: See “Public Accountability and holding to Account” on the Centre for Public Accountability site: www.centreforpublicaccountability.org, accessed 6 April 2015.