Part 2: Public sector arrangements for fulfilling settlements

2.1

After a settlement Act passes, multiple public organisations become responsible for providing redress to the relevant post-settlement governance entity.

2.2

Until February 2025, Te Arawhiti was responsible for overseeing how the Crown met its settlement commitments. A framework, He Korowai Whakamana, set out oversight and monitoring arrangements. These included requirements for core Crown agencies to report their progress in meeting their commitments and a pathway for resolving issues.

2.3

In this Part, we outline these arrangements and discuss how the number of settlements has increased, and how the nature of redress has evolved over time.

Settlements have a clear purpose

2.4

A settlement is intended to acknowledge historical injustices that the Crown perpetrated against iwi and hapū, provide compensation (also called redress), and establish the basis for a renewed relationship. Figure 1 sets out an overview of the settlement process.

2.5

This purpose is set out in settlement negotiation policy, deeds of settlement, and settlement legislation. For example, the Government's settlement negotiation policy states that settlements are intended to:

- explicitly acknowledge historical injustices experienced by iwi and hapū that were caused by the Crown's actions or omissions;

- settle all iwi and hapū claims arising from the Crown's historical injustices;10

- be durable, which means they must be fair, be achievable, and remove the sense of grievance;

- provide financial, commercial, cultural, and other redress that balances fairness to iwi and hapū with the Crown's fiscal and economic constraints; and

- form the basis for strengthening the Crown's relationship with iwi and hapū.11

Figure 1

The process from negotiating to ratifying a Treaty settlement

| Preparing claims for negotiations |

|---|

|

A historical claim or claims about breaches of te Tiriti o Waitangi is registered with the Waitangi Tribunal. If the Crown agrees that there has been a breach of te Tiriti o Waitangi (often but not always after a Waitangi Tribunal inquiry report), the iwi or hapū represented by the claim(s) can negotiate with the Crown. What is “the Crown”?“The Crown” refers to the Executive branch of government and stands for the historical authority of the Queen or King as head of state. Today, the Executive is made up of the Governor-General, Ministers in Parliament, and their government departments.

|

| Pre-negotiations |

|

Both parties write and sign terms of negotiation. Redress is identified – this can take the form of financial payments, one-off commitments (such as the transfer of public land or restoration of a traditional place name), or ongoing commitments (such as establishing co-governance arrangements for a natural feature). |

| Negotiations |

|

Formal negotiations take place. A deed of settlement is drafted – this contains the Crown’s final offer. |

| Ratification and implementation |

|

The deed of settlement is ratified and signed. A governance entity is ratified by iwi and hapu members.

|

Source: Adapted from Office of Treaty Settlements (2018), Ka tika ā muri, ka tika ā mua — Healing the past, building a future: A Guide to Treaty of Waitangi Claims and Negotiations with the Crown (the Red Book), at whakatau.govt.nz.

2.6

The text of each deed of settlement and settlement Act includes the Crown's acknowledgement of the iwi or hapū group's grievances and the Crown's apology. Together, these set out the government's aspirations for the settlement. For example, Te Kawerau ā Maki Claims Settlement Act 2015 states:

The Crown unreservedly apologises for not having honoured its obligations to Te Kawerau ā Maki under the Treaty of Waitangi. Through this apology and this settlement the Crown seeks to atone for its wrongs and lift the burden of grievance so that the process of healing can begin. By the same means the Crown hopes to form a new relationship with the people of Te Kawerau ā Maki based on mutual trust, co-operation, and respect for the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles.12

2.7

Together, these texts articulate the intent of both Cabinet and Parliament. They provide context for the settlement agreement and the redress contained within it.

2.8

Settlement legislation has historically received cross-party support.

Deeds of settlement and settlement Acts assign responsibilities for individual commitments

2.9

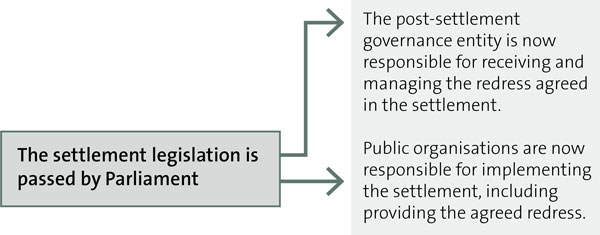

Settlements are given effect through deeds of settlement, which are signed by the iwi or hapū and the Executive, through Cabinet. Generally, deeds of settlement are conditional on being enacted into law by Parliament through settlement Acts.

2.10

As of November 2024, about 100 deeds of settlement have been reached, and 80 of these have been enacted through legislation.13 About 26 settlements remain to be negotiated, and five are pending enactment through legislation.14

2.11

Deeds of settlement and settlement Acts set out the accountabilities for individual commitments. They explain each settlement's purposes and functions, the commitments that have been agreed, and which Ministers and public organisations are responsible for fulfilling them. In doing so, they place contractual and legal obligations on those parties to provide the redress set out in the deed.

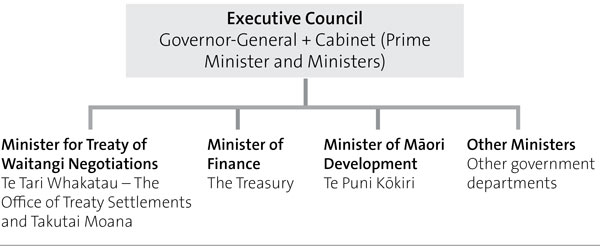

2.12

A range of public organisations are responsible for providing settlement redress, including Ministries and departmental agencies, Crown entities, State-owned enterprises, and local authorities. Each public organisation is accountable to its Minister or relevant governing entity for complying with its contractual and legal obligations to fulfil individual settlement commitments.

2.13

Ministers are accountable to Parliament for the actions and omissions of the public organisation(s) that they are responsible for. Other governing entities, such as elected council members, are accountable to the communities that elected them for the actions and omissions of the public organisation(s) that they are responsible for.

2.14

In some instances, the governing entity is responsible and accountable for individual commitments. For example, Ministers can be formally responsible for sending letters of introduction (see paragraph 2.16).

2.15

Post-settlement governance entities receive and manage redress.

Various types of commitments are included in settlements

2.16

Settlements contain a range of types of commitments. Some are one-off commitments, such as:

- transfers of public land, including through:

- properties transferred on the settlement date;

- rights of first refusal, where post-settlement governance entities retain a long-term right to be given the opportunity to buy land a public organisation disposes of; and

- deferred selection properties, where post-settlement governance entities can choose to buy properties within a set time frame;

- Ministers sending letters of introduction to other public organisations encouraging them to establish relationship agreements with post-settlement governance entities;

- paying financial redress; and

- restoring traditional place names.

2.17

Other redress types involve ongoing commitments, such as:

- relationship agreements, protocols, and forums between post-settlement governance entities and public organisations;

- co-management and/or co-governance arrangements for natural features, such as the Waikato River; and

- ongoing consultation on strategy and planning processes (such as conservation management strategies and plans) or on regulatory matters (such as regional plans or resource consent applications).

Public organisations must consider settlements' overall intent when meeting commitments

2.18

In December 2022, Cabinet endorsed a set of expectations for core Crown agencies about how to meet settlement commitments "so that settlements are durable and support true Treaty partnership".15 In March 2024, Te Arawhiti issued guidance reinforcing these expectations.16

2.19

These expectations confirm what deeds of settlement and settlement Acts already set out:

- Any redress that has been committed to is a contractual and legal obligation that responsible public organisations must fulfil.17

- Settlements commit parties to a "renewed relationship"18 and provide a foundation for an enduring "Treaty partnership".19

2.20

These expectations also state that, although agencies are "responsible for individual commitments to iwi, it is important to be mindful of the holistic intention of the settlement rather than solely focusing on implementation of individual commitments".20 In other words, meeting individual commitments and pursuing a renewed relationship are interdependent.

2.21

This might involve seeking to realise the aspirations of iwi and hapū through "partnership opportunities beyond specified redress".21 It might also involve understanding the settlement's context, any interdependencies with commitments that other agencies hold, and co-ordinating with other agencies to provide redress (see Part 3).

The number and complexity of commitments have increased over time

2.22

Since the first settlement negotiations began in 1989, the number of settlements have effectively doubled each decade until 2020. Eleven deeds of settlement were agreed between 1989 and 2000, 24 between 2001 and 2010, 52 between 2011 and 2020, and at least 13 since 2021. Through the process of achieving settlements between iwi and hapū and the Crown, public organisations have become responsible for increased volumes of settlement redress.

2.23

Today, about 150 public organisations are responsible for about 12,000 individual settlement commitments. In some instances, public organisations are responsible for hundreds of commitments. Four public organisations are each responsible for more than a thousand commitments.

2.24

Settlements have also become more complex over time. Early settlements were about a single claim or issue. However, since 1999, Governments have preferred to seek settlements with what it terms "large natural groupings" – with "groups of tribal interests, rather than with individual hapū or whānau within a tribe".22

2.25

As a result, public organisations are responsible for settlements that can involve a wide range of redress, which can sometimes be novel and complex. Settlements can involve public organisations using existing tools and procedures to provide redress (such as financial and property transfers) or including post-settlement governance entities in existing processes (such as consulting with them as part of developing strategies and plans and carrying out regulatory processes).

2.26

Settlements can also require public organisations to set up new processes and sometimes new entities. Co-governance and co-management arrangements often require public organisations to work with iwi and hapū in ways that they have not previously – even if they have had pre-existing relationships with the same groups.

2.27

The nature of negotiations means that, although most or all settlements feature common redress types, some types of redress are tailored to individual settlements. We were told that this is likely to continue to be the case for the settlements that are yet to be negotiated and agreed. We were also told that some complex settlements are yet to be negotiated.

Oversight arrangements were strengthened in December 2022

2.28

In December 2022, the then Minister for Māori Crown Relations – Te Arawhiti said:

Currently the delivery of settlement commitments rests with each individual commitment holding agency. There is no unified Crown system requiring all those organisations to monitor or report on the progress of their commitments. The Crown lacks assurance that settlements are being honoured. The Crown is also unable to provide that assurance to iwi. This is a significant risk to Māori Crown relationships. When settlement commitments are not honoured, this undermines the confidence of iwi in the Crown and can involve a slow and expensive process to resolution.23

2.29

Cabinet subsequently approved a framework, called He Korowai Whakamana, "for achieving oversight and enhancing accountability" of settlement commitments. Figure 2 sets out the framework's components.

Figure 2

Components of He Korowai Whakamana

|

He Korowai Whakamana He Korowai Whakamana is a framework for overseeing settlement commitments. The framework has:

|

Source: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", at whakatau.govt.nz.

2.30

He Korowai Whakamana applies to "core Crown agencies", which it defines as public service departments and departmental agencies, the New Zealand Defence Force, and the New Zealand Police.

2.31

The framework excludes all other public organisations with Treaty settlement commitments, including Crown entities and local authorities. The Cabinet paper that proposed He Korowai Whakamana recognised that there was an opportunity to consider extending it to other public organisations after core Crown agencies had implemented it.24

Te Arawhiti's mandate was strengthened

2.32

Before He Korowai Whakamana was introduced in December 2022, Te Arawhiti – and its predecessor agencies the Office of Treaty Settlements and the Post Settlement Commitments Unit, which were both part of the Ministry of Justice – already had a mandate to support the fulfilment of Treaty settlement commitments. This included providing proactive guidance and support to core Crown agencies about meeting their commitments and addressing specific issues.25

2.33

However, Te Arawhiti told us that, with limited resources, it had prioritised supporting public organisations with significant settlement issues (such as to prevent a settlement breach or where a breach had already occurred).26 As a result, its involvement in supporting public organisations to meet settlement commitments more generally tended to be reactive.

2.34

Through He Korowai Whakamana, Cabinet approved a strengthened mandate for Te Arawhiti "to lead the system to achieve oversight of delivery of core Crown Treaty settlement commitments".27 This included:

- providing guidance, advice, and support to core Crown agencies – including discrete advice when requested;28

- maintaining clear expectations for core Crown agencies;29

- monitoring core Crown agencies' commitments through Te Haeata – the Settlement Portal;

- administering the resolution pathway when post-settlement issues involving core Crown agencies had been escalated; and

- preparing a whole-of-system report on the status of core Crown agencies' commitments for 2023/24 onwards.

New monitoring and reporting arrangements were introduced

2.35

Te Arawhiti developed Te Haeata from an older list of individual commitments derived from deeds of settlement and settlement Acts.30 It now contains about 12,000 commitments tagged to the entities responsible for meeting them.

2.36

More than one public organisation is responsible for some commitments, leading to an overall number of about 18,000 responsibilities. Of these responsibilities:

- core Crown agencies are responsible for about 80%; and

- Crown entities, local authorities, and other non-core Crown agencies are responsible for about 20%.

2.37

He Korowai Whakamana requires core Crown agencies to provide quarterly updates in Te Haeata on the status of each commitment they are responsible for. It also requires core Crown agencies to report on their settlement commitments in their annual reports from 2023/24 onwards. The Treasury has issued guidance to assist core Crown agencies with these requirements.31

2.38

Although Te Haeata lists the commitments of Crown entities, local authorities, and other non-core Crown agencies, these organisations are not required to provide status updates or information about their commitments in their annual reports.

2.39

Through He Korowai Whakamana, Cabinet also directed Te Arawhiti to produce a report on the status of core Crown Treaty settlement commitments for the Minister for Māori Crown Relations. It released the first report, for 2023/24, in December 2024 (see paragraphs 6.65-6.67).

A resolution pathway was set up

2.40

He Korowai Whakamana formalised a resolution pathway that can be used when a settlement issue arises. In March 2024, Te Arawhiti released guidance reinforcing the resolution pathway process.32 A settlement issue arises when a commitment has not or cannot be met as intended – for example, within the specified time frame.33

2.41

The pathway allows for the following three levels of response to a settlement issue:

- "Resolve" is triggered when a post-settlement governance entity or core Crown agency raises a settlement issue with Te Arawhiti (now with Te Puni Kōkiri). The public organisation involved notifies Te Puni Kōkiri, updates Te Haeata, then works with the post-settlement governance entity to resolve the issue (with advice and support from Te Puni Kōkiri if needed).34

- "Re-establish" is triggered for significant settlement issues. At this step, the relevant public organisation's chief executive and the Public Service Commissioner are formally notified.35

- "Report" is triggered if the agreed pathway to resolution has not been met and partners cannot agree on adjustments to time frames.36

2.42

The final step (Report) includes a series of escalations. This includes a report to the relevant Ministers, who then provide direction on the next steps.37

2.43

If the public organisation cannot resolve the issue with the post-settlement governance entity, Ministers may request the Māori Crown Relations Cabinet Committee or Cabinet to provide further direction.38

He Korowai Whakamana is yet to be fully embedded

2.44

Implementation of He Korowai Whakamana started in 2023, but aspects of it had not been fully embedded when we carried out our audit. For example, the Public Service Commissioner had yet to be formally notified of any significant settlement issue, in part because the Commissioner's role after being notified had not yet been worked out (see paragraphs 5.27-5.35).

2.45

Aspects of Te Arawhiti's strengthened mandate and its processes and procedures for reporting the status of commitments in Te Haeata were also still new. Public organisations were only required to publicly report from 2023/24.

2.46

As mentioned in paragraphs 1.19-1.20, in late 2024, the Ministers of Treaty for Waitangi Negotiations and Māori Crown Relations decided to transfer responsibility for many of Te Arawhiti's functions to Te Puni Kōkiri. This included responsibility for monitoring and reporting on the Crown's fulfilment of commitments. When we published this report, these changes had only recently been implemented.

2.47

We expect that it will take more time for Te Puni Kōkiri to fully embed He Korowai Whakamana alongside its new responsibilities. This report aims, in part, to assist Te Puni Kōkiri in identifying and making improvements to support public organisations to fulfil settlements.

2.48

Te Puni Kōkiri has been given significant responsibilities, which are crucial to strengthening the Crown's relationship with iwi and hapū. A critical step will be to build constructive relationships with post-settlement governance entities.

2.49

We intend to follow up on the progress public organisations have made on our recommendations in due course.

10: The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 defines historical claims as claims relating to acts or omissions of the Crown that occurred before 21 September 1992 (see section 2 of the Act).

11: Office of Treaty Settlements (2018), Ka tika ā muri, ka tika ā mua — Healing the past, building a future: A Guide to Treaty of Waitangi Claims and Negotiations with the Crown (the Red Book), at whakatau.govt.nz.

12: Section 9(3) of Te Kawerau ā Maki Claims Settlement Act 2015.

13: Te Arawhiti (2024), Whole of System (Core Crown) Report on Treaty Settlement Delivery, page 5, at beehive.govt.nz.

14: Te Arawhiti (2024), Whole of System (Core Crown) Report on Treaty Settlement Delivery, page 5, at beehive.govt.nz

15: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", Appendix 3, at whakatau.govt.nz.

16: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, at tpk.govt.nz.

17: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, page 2, at tpk.govt.nz.

18: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, page 2, at tpk.govt.nz.

19: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, page 3, at tpk.govt.nz.

20: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, page 3, at tpk.govt.nz.

21: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, page 3, at tpk.govt.nz.

22: Office of Treaty Settlements (2018), Ka tika ā muri, ka tika ā mua — Healing the past, building a future: A Guide to Treaty of Waitangi Claims and Negotiations with the Crown (the Red Book), page 39, at whakatau.govt.nz.

23: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", paragraph 14, at whakatau.govt.nz.

24: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", paragraph 23, at whakatau.govt.nz.

25: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", paragraph 18, at whakatau.govt.nz.

26: Te Arawhiti's guidance defines a significant settlement issue as a case where:

… one or more of the following factors are present:

- the Deed or Legislation has been breached;

- the redress cannot be delivered as intended;

- an all-of-Crown view is required;

- there is a material relationship breakdown between parties;

- there is a lack of reasonable progress or engagement;

- a number of issues have arisen, and the cumulative impact is significant.

See Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", page 24, at whakatau.govt.nz.

27: Te Arawhiti (2023), "Proactive release – He Korowai Whakamana – Enhancing oversight of Treaty settlement commitments", paragraph 58.5, at whakatau.govt.nz.

28: The Crown Law Office also provides legal advice to core Crown agencies when requested.

29: We discuss these expectations in paragraphs 2.18-2.21. Cabinet endorsed the original version of these expectations, and they were released in December 2022. Te Arawhiti reissued these expectations in March 2024: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance for Crown: Crown expectations for Crown Treaty settlement commitments, at tpk.govt.nz.

30: The Post Settlement Commitments Unit in the Ministry of Justice, which was set up in 2013, started developing the original list. This unit was absorbed into Te Arawhiti, which became operational in 2019.

31: The Treasury (2024), Annual reports and other end-of-year performance reporting: Guidance for reporting under the Public Finance Act 1989, pages 42-44, at treasury.govt.nz.

32: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, at tpk.govt.nz.

33: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, page 2, at tpk.govt.nz.

34: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway page 4, at tpk.govt.nz.

35: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, pages 4-5, at tpk.govt.nz.

36: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, page 5, at tpk.govt.nz.

37: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, pages 5-6, at tpk.govt.nz.

38: Te Arawhiti (2024), Guidance: Crown post-settlement issues resolution pathway, page 6, at tpk.govt.nz.