Part 3: The Ministry of Education needs better information

3.1

Having more comprehensive knowledge about inequity in student achievement and progress would allow the Ministry of Education to identify what factors cause inequity and to design initiatives that schools can use to address inequity. The Ministry needs the right information to attain this knowledge.

3.2

We expected the Ministry to obtain and maintain the information it needs to:

- have a comprehensive view of student achievement and progress for Years 1-13;

- identify which students are meeting achievement expectations and which are not; and

- plan to address any gaps in information that limit its ability to understand student achievement and progress.

3.3

In this Part, we discuss how the Ministry:

- does not have comprehensive information about student achievement or progress, especially for Years 1-10 and for Māori-medium education; and

- needs to work with others to address the gaps in its information.

Summary of findings

3.4

The Ministry gets information about student achievement from several sources, including schools, NCEA results, and international comparative studies. It also collects information through regular studies of the achievement of a sample of primary school students.

3.5

These sources provide some useful information about student achievement and proficiency.

3.6

However, during our audit, the Ministry acknowledged that it needs better information about the achievement and progress of Year 1-10 students.

3.7

The Ministry told us that it also recognises that there are other gaps in its information, such as:

- the achievement and progress of students in Māori-medium education in Years 1-10;

- the achievement and progress of students with disabilities, students with additional learning needs (including neurodiverse students), and LGBTQIA+ students;

- the abilities of new entrants; and

- the effect of transitioning from primary to secondary school.

3.8

These gaps limit the Ministry's knowledge about inequity in achievement and progress, including about which students are affected, what factors cause inequity, and how these factors interact for different student groups. This affects the Ministry's ability to design initiatives and interventions that best address inequity.

3.9

The Ministry has plans to address some of these information gaps, but we consider that it needs to do more. The Ministry needs to work with schools and other education organisations to identify what information is needed to fully understand student achievement and progress.

3.10

Although this work will be challenging and take time, it will be essential to enabling the Ministry to develop initiatives to address inequity using a wider range of evidence than is currently available.

The Ministry of Education does not have comprehensive information about student achievement or progress in Years 1-10

3.11

NCEA results provide the Ministry with comprehensive information about student achievement in Years 11-13. We discuss this further in paragraphs 3.55-3.59.

3.12

However, the Ministry does not have a framework or approach for receiving up-to-date and comprehensive information about student achievement and progress against the National Curriculum for Year 1-10 students.

3.13

Instead, the Ministry gets information from:

- sample studies of student achievement – these were a sample of students in Years 4 and 8 before 2023, and a sample of students in Years 3, 6, and 8 from 2023;

- student assessment tools developed to help teachers customise their teaching practice for individual students; and

- international comparative studies of student proficiency in literacy, maths, and science.

3.14

Appendix 2 summarises the sources of the information that the Ministry has about student achievement, progress, and proficiency in Years 1-13.

The Ministry has 10 years' worth of information about student achievement in Years 4 and 8

3.15

The National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (the monitoring study) is a formal sample study that produces a snapshot of student achievement against The New Zealand Curriculum. Originally, it collected information about student achievement in Years 4 and 8. The study was updated in 2023 and now collects information about Years 3, 6, and 8.

3.16

The monitoring study is a collaboration between the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, the University of Otago Educational Assessment Research Unit, and the Ministry.

3.17

The original monitoring study was carried out over 10 years. It focused on different subjects in different years. For example, it reported on achievement in maths and statistics in 2013, 2018, and 2022, in science in 2012 and 2017, and in aspects of the English curriculum (such as reading or writing) in 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2019.

3.18

The last round of the original monitoring study (on maths and statistics) involved about 2000 students in each year level studied.

3.19

The monitoring study identified trends in achievement for students in English-medium education, including trends for particular groups of students. For example, trends are available for broad categories such as gender (boys and girls), ethnicity (European/Pākehā, Māori, Pacific, and Asian), and schools' decile band (which were based on the socioeconomic status of the community).

3.20

The monitoring study highlighted inequity between these student groups for some subjects.

3.21

For example, the 2022 results for maths found that achievement was linked to school decile. Students from low to mid-decile schools did not achieve as well as those from higher decile schools. The monitoring study estimated that on average, at Year 8, the difference was equivalent to two and half years of progress.

3.22

There were similar results in the 2019 study of achievement in English, which found that a higher decile band was related to higher achievement in writing, speaking, reading, presenting, listening, and viewing.

3.23

The monitoring study also found differences in achievement by students' gender or ethnicity. For example, when it compared the 2022 results for maths and statistics with the 2018 results, it found no statistically significant change in average scores for students as a whole. However, it found statistically significant declines in average scores for Year 8 Māori and Pacific students and for Year 8 girls.

3.24

The monitoring study consistently found that differences in achievement by socioeconomic status were larger than differences by gender or ethnicity.

3.25

The monitoring study had the following limitations:

- It focused on students in English-medium education. It did not include students in Māori-medium education.

- Its design and sample size meant that achievement trends are not available for other student identifiers. For example, the monitoring study did not collect information about students' neurodiversity, disability status, gender identity, or sexuality.

- The monitoring study was limited in its ability to track student progress because each year's study looked at a different sample group of students. Although the results from each round of the monitoring study allowed student achievement at Years 4 and 8 to be compared over time, they could not show how particular groups of students had progressed between Years 4 and 8.

The monitoring study was updated in 2023 and now collects more information

3.26

After being updated in 2023, the monitoring study is now called the Curriculum Insights and Progress Study and assesses student achievement against expectations at Years 3, 6, and 8 instead of at Years 4 and 8.

3.27

The updated study will assess each subject in The New Zealand Curriculum once every four years. The original study assessed each subject once every five years.

3.28

The updated study will also assess students with additional learning needs. This will allow the Ministry to look at the impact of any extra support these students receive.

3.29

The updated study will also assess the annual progress of a cohort of students in literacy and numeracy. The cohort study should provide the Ministry with reliable information about student progress in English-medium education for the first time. It will also provide additional data about student achievement.

3.30

However, the updated study will not provide information about the achievement or progress of students in Māori-medium education. We discuss this further in paragraphs 3.60-3.72.

An online learning and assessment tool provides some insights about student achievement and progress

3.31

The Ministry developed and maintains the Assessment for Teaching and Learning online tool.9 Teachers can use it to assess student achievement and progress in reading, maths, and writing (in English-medium education) and in pānui, pāngarau, and tuhituhi (the corresponding areas in Māori-medium education).

3.32

The assessments relate to curriculum levels 2-6 for reading and maths and levels 1-6 for writing. These correlate to students in Years 5-10 for reading and maths and in Years 1-10 for writing.

3.33

Schools can – and do – share the information from the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool with the Ministry. When schools have carried out enough assessments, the Ministry may, with schools' permission, use this information to comment on aspects of student progress.

3.34

However, the Ministry told us that the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool is not suitable for monitoring student progress or generalising about achievement for all students. This is because:

- the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool is mainly used in English-medium education and is not used in all school year levels consistently;

- using the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool is voluntary, which means that the information it produces does not come from a randomly selected sample of schools and might not be representative; and

- fewer than half of all schools use the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool, and some only use it occasionally.

3.35

As a result, information from the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool has been of limited use in helping the Ministry to investigate what factors contribute to educational inequity.

3.36

We understand from recent announcements that schools are going to more consistently use the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool to monitor student achievement from 2025.

3.37

Schools will be required to use either the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool or another form of standardised assessment to test children in Years 3-8 in reading, writing, and maths twice a year.

International studies provide information on student proficiency

3.38

The Ministry also receives information from international comparative studies (see paragraphs 1.5-1.7). These provide regular and valuable insights about students' proficiency in particular subjects.

3.39

The studies do not test students against The New Zealand Curriculum. However, they do allow the proficiency of New Zealand students in specific subjects to be compared with students in other countries.

3.40

These studies all focus on students enrolled in English-medium education and are carried out in English.

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

3.41

New Zealand has been involved in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study since 1994. This takes place every four years and looks at student proficiency in maths and science at Year 5 and Year 9.

3.42

The study uses questionnaires completed by students, their parents or caregivers, teachers, and school principals to find out about aspects of students' contexts for learning (such as students' attitudes to learning and their socioeconomic circumstances).

3.43

The most recently published results (from 2019) show relative stability since 1994 in maths and science scores at Year 5 and a gradual decline in scores at Year 9.

3.44

The 2019 results also highlighted that socioeconomic status is a significant factor in achievement. For example, average results at Years 5 and 9 for students with greater access to learning resources at home (a measure of socioeconomic status) were significantly higher than for students with fewer resources.

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

3.45

New Zealand is part of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, which began in 2001. This study takes place every five years and looks at reading literacy proficiency at Year 5.

3.46

The 2021 results overall showed no significant changes in the average (mean) results, the distribution of scores, or the proportions of Year 5 students reaching each of the study's reading benchmarks compared to the 2016 study.

3.47

These studies have found that, on average, students with higher socioeconomic status score much higher than those with lower socioeconomic status. The 2021 results noted that this gap in average scores was higher than the gap found in many other countries.

3.48

The average score for Māori and Pacific boys was lower than for Māori and Pacific girls. This occurred even though the gap in average achievement between all girls and boys was narrowing. The average difference between Pacific girls' and boys' achievement scores was the largest of any ethnic group.

Programme for International Student Assessment

3.49

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a significant international study that the OECD carries out every three years. It assesses 15 year olds' proficiency in maths, reading, and science.10 New Zealand has participated in PISA since 2000.

3.50

Each assessment round tests one subject in detail. The main subject was maths in 2003, 2012, and 2022. Reading was the main subject in 2000, 2009, and 2018, and science was the main subject in 2006 and 2015.

3.51

Between 2003 and 2022, average scores in all subjects declined. This is true for New Zealand and many similar countries.11 Throughout this period, New Zealand students have continued, on average, to perform similarly to or better than their international counterparts.

3.52

The 2022 PISA results for maths show that the proficiency of low achievers declined by more than that of high achievers. The gap between the highest-scoring students (the 10% with the highest scores) and the lowest-scoring students (the 10% with the lowest scores) widened.

3.53

The same report found that, for reading and science, there was no significant change in the average results or the gap between high and low achievers.

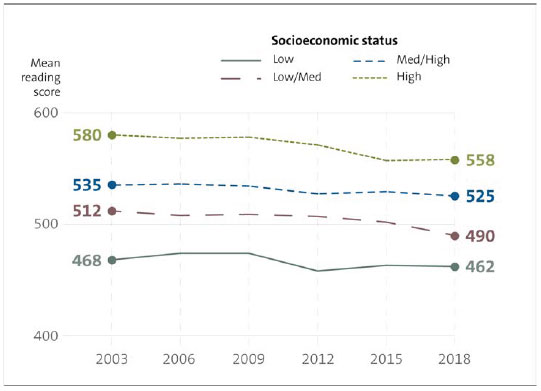

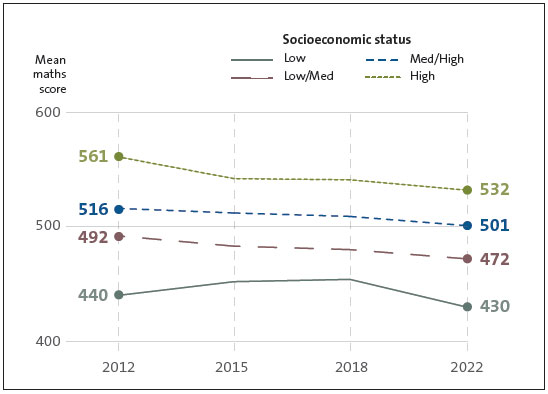

3.54

As Figures 1 and 2 show, the results also revealed that students with higher socioeconomic status (the top 25%) significantly outperformed those with lower socioeconomic status (the bottom 25%). This gap was more significant than those for gender or ethnicity.

NCEA results provide the most comprehensive view of achievement from Years 11-13

3.55

The Ministry's most comprehensive information about student achievement comes from NCEA results for Year 11-13 students. This information covers participating students and schools in all the subjects offered.

3.56

Since 2020, the number of students achieving all three levels of NCEA has declined slightly. The New Zealand Qualifications Authority reported that there is a "significant underlying equity gap" and that Māori and Pacific students attain NCEA Levels 1 to 3 at lower levels than European and Asian students.12

Figure 1

Programme for International Student Assessment – mean scores for reading (2003-2018)

Note: PISA scores are scaled to fit approximately normal distributions, with means of about 500 score points. Source: Education Counts (educationcounts.govt.nz).

Figure 2

Programme for International Student Assessment – mean scores for maths (2012-2022)

Note: PISA scores are scaled to fit approximately normal distributions, with a mean of about 500 score points. Source: Education Counts (educationcounts.govt.nz).

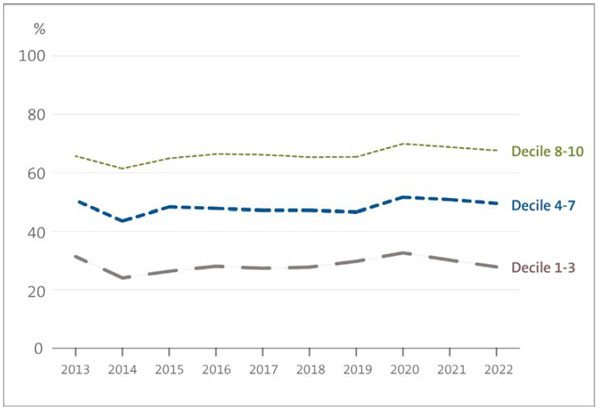

3.57

Significant differences can also be seen when comparing how many students are awarded University Entrance (the minimum requirement needed for a student to go from school to a New Zealand university). Students at low decile schools achieve University Entrance at less than half the rate of those at high decile schools (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Percentage of students who achieve University Entrance by school decile (2013-2022)

Source: Education Counts (educationcounts.govt.nz).

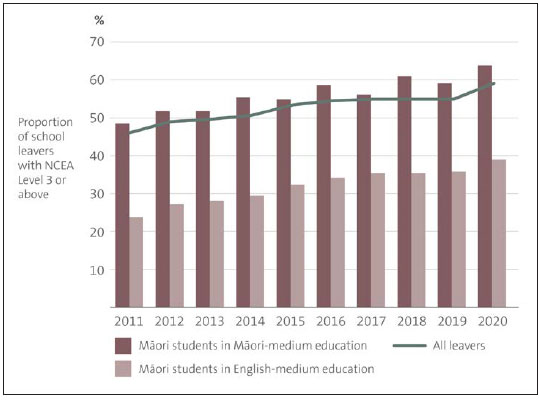

3.58

These equity issues are not consistent throughout the education system. For example, students in Māori-medium education attain NCEA Level 3 at rates significantly higher than Māori students in English-medium education.

3.59

A 2022 Ministry report looked at the qualifications attained by school leavers in 2020. It said that 64% of Māori students in Māori-medium education left school with NCEA Level 3 or above, compared to 59% for all school leavers (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Proportion of Māori students attaining NCEA Level 3 in different education settings (2011-2020)

Source: Ministry of Education (2022), Ngā Haeata o Aotearoa 2020, at educationcounts.govt.nz.

There are significant gaps in the Ministry of Education's information, especially for Māori-medium education

3.60

Although NCEA results provide achievement information for Māori-medium Year 11-13 students, the Ministry has limited information about achievement and progress for students in Māori-medium education in Years 1-10.

3.61

As at 1 July 2023, 25,824 students were in Māori-medium education. The only information that the Ministry gets about these students is for Years 1-10 for literacy in English and te reo Māori, mainly through the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool (see paragraphs 3.31-37) and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (see paragraphs 3.45-3.48).

3.62

In our view, this is a critical gap. The Ministry has a role in helping whānau, teachers, and schools to identify and meet the needs of students in Māori-medium education.

3.63

To do this, the Ministry needs to know whether there are differences in the achievement and progress of students in Māori-medium education compared to other students before they start NCEA. Understanding any differences could help the Ministry better identify factors that support achievement and progress for Māori students and factors that become barriers.

3.64

The Ministry also needs more information about children's abilities when they start school, which would provide a clearer picture of the progress students make during their first years at school. As we discuss in paragraph , the widely varying abilities of new entrants is a challenge for many schools.

3.65

The Ministry could also strengthen its efforts to address educational inequity if it had information about:

- how students are affected by transitions during their education, such as the move from primary school to secondary school; and

- the achievement and progress of particular groups of students, such as students with disabilities, students with additional learning needs (including neurodiverse students), and LGBTQIA+ students.

3.66

During our audit, the Ministry acknowledged that there are significant gaps in information about student achievement and progress, including those identified above.

3.67

It has also acknowledged these gaps in its publications. For example, the Ministry's 2022 report Ngā Ara o te Mātauranga – the pathways of education stated that it has "relatively good information on [students'] participation and attendance" and "overall achievement at secondary school".

3.68

However, the report said that the Ministry has less information "on progress and achievement throughout schooling and the extent to which teaching is responsive and inclusive". The report also said that there is "very limited information on the success of [students] in Māori medium and kaupapa Māori settings" and "extremely limited information on the participation and success of disabled [students]".

3.69

These gaps limit the Ministry's ability to gain a clear and detailed picture of when inequity in achievement and progress occurs, which students are affected, what factors are causing inequity, and how different factors might interact.

3.70

In turn, this limits the Ministry's ability to design initiatives and interventions that best address inequity in student achievement. We discuss the Ministry's approach to designing initiatives and interventions in Part 4.

There are opportunities for the Ministry to address gaps in its information

3.71

We understand that there have been discussions about setting up a study for Māori-medium education that corresponds with the Curriculum Insights and Progress Study (see paragraphs 3.26-3.30). However, when we wrote this report, no decisions had been made about this.

3.72

In our view, the Ministry needs to continue working with Māori-medium schools and kura kaupapa Māori on introducing such a study. This could help the Ministry better understand the achievement and progress of Year 1-10 students and what more the Ministry, kura, and schools can do to support Māori students to reach their potential and to better identify and address the challenges these students might have.

3.73

During our audit, the Ministry was developing assessment practices, tools, and guidance to support schools to use:

- the Common Practice Model for reading, communications, and maths for English-medium education; and

- the corresponding Ako Framework for te reo matatini and pāngarau for Māori-medium education.

3.74

The Common Practice Model and the Ako Framework identify the progress that students are expected to make at particular points throughout the National Curriculum. When the Ministry develops the related assessment tools, they should help teachers understand whether students are meeting achievement expectations.

3.75

Assessment tools are a way for teachers to identify any challenges that affect student learning. This means that they can customise their teaching practices to help students to progress.

3.76

In our view, these developments could help the Ministry fill gaps in its information about student achievement and progress. We understand that schools can choose whether to use these assessment tools.

3.77

If enough schools use the assessment tools and agree to share the resulting information, it could provide the Ministry with a source of consistent and up-to-date information about the achievement and progress of Year 1-10 students in reading, communications, and maths.

3.78

Analysing this aggregated information would help the Ministry better understand variations in achievement for many more students (compared to the information provided by the Assessment for Teaching and Learning tool).

3.79

Aggregated assessments would also provide the Ministry with real-time feedback on the effectiveness of the refreshed National Curriculum and what improvements might be needed. They would also provide a feedback loop to schools, and provide context for the results of the Curriculum Insights and Progress Study.

The Ministry of Education needs to work with others to address gaps in its information

The Ministry needs more effective working relationships with schools and the wider education system

3.80

The Ministry will need to work closely with schools to improve its information about student achievement and progress. It will also need to work with other organisations, such as the Education Review Office and the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

3.81

All those involved will need to have confidence that:

- the relevant parties will collect information consistently and reliably;

- the information will be used appropriately at all levels of the education system, from the classroom to the Ministry; and

- parties supplying information will get feedback on how that information is used and the results of any analysis.

3.82

Schools can face multiple challenges that affect their ability to support students. Working with the Ministry to improve its access to information about achievement and progress might not be a top priority for some schools.

3.83

A 2023 report from the New Zealand Council for Educational Research stated that many schools are prioritising students' basic needs – making sure that children were fed, clothed, warm, and healthy – so that they are able to learn.13

3.84

Some schools are funding breakfast and lunch for students and providing school uniforms, jackets, shoes, and socks. One school said in the report that many of its new entrants had not had hearing checks or immunisations, and they work with parents and health services to arrange for these to take place at school.

3.85

Schools told us that teachers and principals can spend a lot of their time dealing with the effects of poverty. This includes schools helping students to cope with:

- homelessness, overcrowded housing, a lack of clothing, or a lack of food;

- mental illness, drug and alcohol issues, family violence, and transience; and

- accessing digital learning resources that their families cannot afford.

3.86

Schools told us that students are starting school with a range of abilities. Some students have under-developed language skills, and others are not toilet trained or have few social skills. Some students have limited English language skills when they start school.

3.87

We also heard that schools are often reluctant to share information about their students' achievement and progress with the Ministry.

3.88

Some schools are concerned about how the information will be used and whether there would be appropriate recognition of the different contexts that each school operates in and the range of challenges that their students face. We understand that schools perceive risks in directly comparing student achievement and progress or school performance.

3.89

The Ministry and schools also face practical challenges when sharing information with each other. People mentioned this during our interviews with Ministry staff, schools, and other education organisations. Schools do not always have the ability and capacity to provide reporting to support efficient analysis by Ministry staff.

3.90

The Ministry will need to consider these issues as it improves how it works with schools to identify, collect, and share relevant and timely information about student achievement and progress. This could include discussions on what a broader view of educational achievement could mean in practice.

3.91

Although this work will be challenging and will take time, we consider that it is essential for developing initiatives that are supported by reliable evidence.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education work with schools and other education organisations to identify what information it needs to develop a better picture of student achievement and progress and what factors can lead to inequity in educational outcomes. |

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education work with schools and other education organisations to develop a plan to collect and share the information it identifies in response to Recommendation 1, including who will collect it, how often they will collect it, how it will be used, and who it will be shared with. |

9: The tool is also known as "e-asTTle".

10: See "Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)" at oecd.org.

11: For example, the 2022 PISA assessment saw, on average, a drop in performance throughout the OECD that can only partially be attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic. Scores in reading and science had already been falling before the pandemic, and negative trends in maths performance were apparent in several countries before 2018. See Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023), PISA 2022 results: The state of learning and equity in education, Volume 1, at oecd.org.

12: See "NCEA and UE 2023 attainment data now available" at nzqa.govt.nz.

13: New Zealand Council for Educational Research (2023), Assessing how schools are responding to the Equity Index, at nzcer.org.nz.