Part 3: Making subsidy payments

3.1

In this Part, we describe:

- how quickly payments were made;

- whether the eligibility criteria were met;

- how adequate the payment system and processes were;

- how effective communication about the Scheme was; and

- how well repayments were managed.

Summary of findings

3.2

Subsidy payments were efficiently managed. Many applications were processed and paid within short time frames. Support was provided to New Zealand employers and, in turn, their employees at a critical time.

3.3

Applicants assessed whether they were eligible, with officials verifying some aspects of the application before making payments. Payments were paid on average within three and a half days of receiving an application. This was well within the Ministry of Social Development's target of five days.

3.4

One eligibility requirement – that a business must have taken active steps to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 – was open to considerable interpretation. As a result, there is a risk that some businesses have received subsidy payments when they could have accessed support from other sources. However, the unclear definition of this requirement means that this cannot be determined with any certainty.

3.5

Nearly $300 million was paid to public organisations. A few large organisations received most of this. In the early stages of the Scheme, there was a lack of clarity about whether public organisations were eligible for subsidy payments.

A significant number of subsidy payments were made quickly

3.6

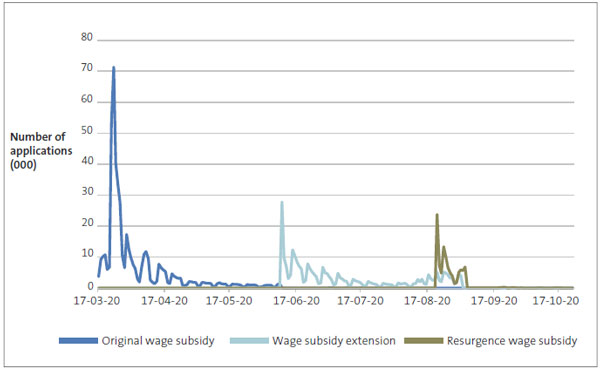

Figure 3 shows the daily number of applications received. The number of applications received within the first two weeks of the Scheme was high. More than 70,000 applications were received on one day.

3.7

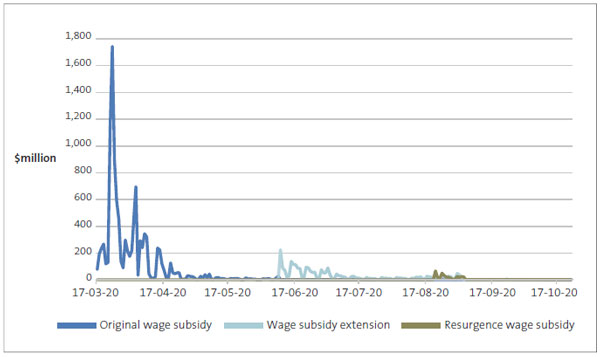

Figure 4 shows the daily amount of payments made. Payments totalling nearly $1.8 billion were made on one day.

3.8

The Ministry of Social Development estimated that, excluding sole traders, the Scheme supported more than half of the jobs in New Zealand at its peak.

Figure 3

Number of applications for the wage subsidy received daily

Source: Our analysis of the Ministry of Social Development's data, produced 23 October 2020, for accepted and declined applications. See the Appendix for information about the limitations of our analysis.

Figure 4

Amount of wage subsidy payments made daily

Source: Our analysis of the Ministry of Social Development's data, produced 23 October 2020, for accepted applications. See the Appendix for information about the limitations of our analysis.

3.9

Figure 5 shows that, on average, payments were made well within the Ministry of Social Development's five-day target. Although most payments were made in a timely manner, a small number of applications took much longer to process. For example, in the early weeks of the Scheme, the average time it took to make payments exceeded the five-day target on several occasions. This reflected the large number of applications during the early weeks of the Scheme.

Figure 5

Average number of days between application and payment, as at 23 October 2020

| Stage | Average number of days to make payment |

|---|---|

| Original wage subsidy | 4.25 |

| Wage subsidy extension | 2.52 |

| Resurgence wage subsidy | 1.82 |

| All three subsidy stages | 3.48 |

Source: Our analysis of the Ministry of Social Development's data. See the Appendix for information about the limitations of our analysis.

Payment amounts varied during the Scheme

3.10

Figure 6 shows the average payment for the original wage subsidy was about $25,000. For the wage subsidy extension (Figure 7) it was about $12,300, and for the resurgence wage subsidy (Figure 8) it was about $3,700. In all three stages of the subsidy, more than 99% of the payments were less than $1 million.

Figure 6

Number and average value of payments for the original wage subsidy stage, as at 23 October 2020

| Value of payment | Number of payments | Total value of payments | Average payment in category |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1 million or less | 440,661 | $8,761,404,360 | $19,882 |

| $1 million to $10 million | 684 | $1,480,626,677 | $2,164,659 |

| $10 million to $20 million | 15 | $195,688,908 | $13,045,927 |

| $20 million plus | 14 | $510,265,982 | $36,447,570 |

| All payments | 441,374 | $10,947,985,927 | $24,804 |

Figure 7

Number and average value of payments for the wage subsidy extension stage, as at 23 October 2020

| Value of payment | Number of payments | Total value of payments | Average payment in category |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1 million or less | 208,709 | $2,416,586,189 | $11,579 |

| $1 million to $10 million | 56 | $116,756,570 | $2,084,939 |

| $10 million to $20 million | 0 | $0 | $0 |

| $20 million plus | 1 | $35,804,672 | $35,804,672 |

| All payments | 208,766 | $2,569,147,430 | $12,306 |

Figure 8

Number and average value of payments for the resurgence wage subsidy stage, as at 23 October 2020

| Value of payment | Number of payments | Total value of payments | Average payment in category |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1 million or less | 84,968 | $301,027,280 | $3,543 |

| $1 million to $10 million | 3 | $16,355,273 | $5,451,758 |

| $10 million to $20 million | 0 | $0 | $0 |

| $20 million plus | 0 | $0 | $0 |

| All payments | 84,971 | $317,382,554 | $3,735 |

Source: Our analysis of the Ministry of Social Development's data. See the Appendix for information about the limitations of our analysis.

Notes: Repayments have not been subtracted from the payment information. At each stage of the Scheme, a small number of organisations received the subsidy payment in more than a single payment.

Eligibility was not always clear

3.11

In Part 5, we describe the Ministry of Social Development's analysis of the types and locations of businesses that received a subsidy payment and the employees who were supported.

3.12

There has been considerable media coverage of, and public interest in, some private organisations that received a subsidy payment. This is particularly so for those that, despite experiencing or projecting a reduction in revenue, have nevertheless paid a dividend to shareholders or otherwise shown financial robustness.

3.13

This does not necessarily prevent private organisations from being eligible for the subsidy. We do not audit private organisations, and we have not assessed the eligibility of any private organisation that received a subsidy payment.

3.14

In the early stages of the Scheme, there was a lack of clarity about whether certain public organisations were eligible. Government agencies, Crown entities, schools, and tertiary education institutions were generally not eligible. Guidance indicated that a State Sector organisation could seek an exemption to become eligible. Local government organisations were eligible.

3.15

More than 200 public organisations applied for a subsidy payment. In total, public organisations were paid nearly $300 million before any decisions were made to return money.

3.16

The largest public organisations that applied had more commercial functions. Cabinet approved their applications on a case-by-case basis. These approvals considered each public organisation's revenue drop and the steps it had taken to manage the impact of Covid-19 on its business. Cabinet gave Television New Zealand, KiwiRail, New Zealand Post, Quotable Value, the New Zealand Artificial Limb Service, and Airways New Zealand access to the subsidy.

Some eligibility criteria might not have been met

3.17

The requirement for applicants to have taken active steps to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 on their business was not clearly defined. Some examples were provided – for example, engaging with their bank or drawing on cash reserves. However, these examples were limited, and employers were not required to make a statement about any active steps they had taken to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 on their business.

3.18

This requirement is important. It tests whether an applicant needs taxpayer-funded assistance. There is a risk that some applicants who did not meet this requirement received payment.

3.19

However, this cannot be determined with any certainty because:

- the definition of the requirement is unclear;

- applicants did not have to provide corroborative evidence at the time of application; and

- we could not identify records that described any actions taken to conclusively verify whether this requirement was met.

3.20

In our view, if the Ministry of Social Development had required applicants to make a statement about what steps they had taken, they might have been more likely to comply with this requirement. As a result, there would have been information that could have been verified in any assurance work carried out after payment was made.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that, when public organisations are developing and implementing crisis-support initiatives that approve payments based on "high-trust", they ensure that criteria are sufficiently clear and complete to allow applicant information to be adequately verified. |

3.21

In our view, this is especially important when high-trust approaches are being used because it is primarily applicants who assess whether they are eligible and not officials.

3.22

Inland Revenue told us that it has followed this recommendation when implementing the Small Business Cashflow Scheme.

Payments were generally well managed

3.23

The main system the Ministry of Social Development had in place to support and record the processing of applications was its Emergency Employment Support system.

3.24

Some automated checking and warning messages were built into the Emergency Employment Support system. Users of the Emergency Employment Support system could record the checks they carried out before approving an application, using a free-text field and drop-down boxes.

3.25

Payments were restricted to the levels outlined in the Scheme's policy – $585.80 each week for a full-time employee and $350.00 each week for a part-time employee. An employee with the necessary delegation and who had not processed the application would sign off on a batch of payments. Ministry of Social Development staff doing post-payment assurance work could not work on applications they had originally approved.

3.26

Only staff with administrator access could change the applicant's bank account details obtained when they applied. The Ministry of Social Development's work included checking for any payments against bank accounts of its staff. That work did not identify any fraudulent payments to Ministry staff.

3.27

Although these processes worked well overall, there were some areas for improvement. The Emergency Employment Support system permitted staff to record information about pre-payment checks, but this was not always done or done consistently. Although we saw records that indicate the Ministry of Social Development generally checked Inland Revenue Department numbers (IRD numbers), it did not always record the specific employee IRD numbers it checked. However, Inland Revenue told us that it kept a record of which customers the Ministry asked about.

3.28

The Ministry of Social Development used existing financial delegations for approval of applications and authorising payments. As part of the 2019/20 annual audit of the Ministry, our appointed auditor recommended that the Ministry consider tightening delegation arrangements in any future stage of the Scheme. Initially, a cap limited subsidy payments to $150,000. When the cap was lifted, applications from employers with more than 80 employees were subject to pre-payment checks that were completed by the Ministry's integrity staff.

It is not clear whether applicants fully understood their obligations

3.29

Once the Scheme had begun, the Ministry of Social Development, Inland Revenue, and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment all had information about it on their websites and social media. There was also information on the Government's Covid-19 website. Although there was a lot of information available, there was no single place to get definitive information about the Scheme.

3.30

It appears that, on balance, having information about the Scheme on multiple websites was considered more appropriate for these circumstances than a single website. We were told that the risk of detracting from important health information on the Government's Covid-19 website was also a reason for not putting all information about the Scheme on that site.

3.31

Although each public organisation involved in the Scheme used its existing communications channels and approaches, all of them worked together to prepare the communications. We were told about some small inconsistencies in the information available on different websites about the purpose of the Scheme and employment-related expectations. These were later corrected. Public organisations did regularly meet to discuss common queries received about the Scheme and queries received from the same organisations.

3.32

There were also some challenges communicating the requirement to comply with employment law and the eligibility criteria. Stakeholders we spoke with felt that communications about the purpose of the Scheme could have been clearer and more focused on the main objective of keeping people employed. Others believed that some of the advice on websites conflicted with employment law and that specific employment-relations information about the Scheme should have featured more prominently on the websites. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment told us that there were improvements to the employment information on Employment New Zealand's website during the Scheme.

3.33

The Ministry of Social Development also assessed that its communication about the Scheme was not completely effective. In late July 2020, the Ministry of Social Development told its leadership team that:

Enquiries from applicants and early auditing showed that many applicants had not fully understood the criteria when they applied, particularly as the Wage Subsidy kept changing, and the interplay between the different stages of the Wage Subsidy was not straight-forward.

3.34

We understand that the Ministry of Social Development sought to improve its communications during the life of the Scheme using this type of feedback.

3.35

Information in the declaration form was the main way possible enforcement action was communicated to applicants. The information included the possibility of applicants being required to repay the subsidy payment. Subsequently, additional information about reviews and enforcement has been added to the Ministry of Social Development's website.

3.36

Although the declaration form was relatively clear, it was lengthy and contained a lot of information. It also changed between the different stages of the Scheme.

3.37

There is a risk that some applicants did not fully read the form or did not fully understand the obligations. Many applicants agreed to the declaration at a time of uncertainty and stress (unrelated to the Ministry of Social Development's actions). The declaration was read out to some applicants over the phone, who agreed to it verbally.

3.38

We were told that it would have been helpful to have had clearer information before people applied about:

- how and when to repay the subsidy payment and what would trigger a repayment; and

- the criteria for repaying the subsidy payment, such as when a business had nearly but not fully reached the revenue drop threshold or had genuinely forecast a revenue drop that did not eventuate.

3.39

We agree that more clarity on when repayments were required could have been helpful given the continually changing situation many applicants were in. The speed at which the Scheme was implemented meant that the repayment processes were not in place when the Scheme was launched. However, they were put in place during the Scheme's first week.

3.40

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment told us that it has recently improved and streamlined its website information about the Scheme. Given it is possible that further stages of the Scheme will be implemented, we encourage public organisations involved in the Scheme to review their communications to ensure that they are consistent and adequate to assist applicants to fully understand their obligations.

A process to manage repayments was established quickly

3.41

The Ministry of Social Development received its first query about repaying a subsidy payment on the second day of the Scheme going live. It received its first repayment on 25 March 2020, just over a week after it had made the first payment. The Ministry had not anticipated such early repayments. It quickly set up a facility to receive payments.

3.42

The Ministry of Social Development subsequently prepared standard letters to send to applicants after reviewing their application. Those letters have a clear statement about the conclusion of the review and the implications for repayment.

3.43

The Ministry of Social Development believes that media coverage, the published list of some recipients, and advice from third parties such as business advisors have all influenced people ineligible for subsidy payments to voluntarily repay.

3.44

As at 5 March 2021, the Ministry of Social Development received 20,973 repayments valued at $726.2 million. This is about 5% of the value of payments made to that date. About $703 million of the repayments were voluntary.

ADDENDUM: This information was supplied to us by the Ministry of Social Development at the time of our audit. The Ministry has since reported different information about the amount of voluntary repayments as at 5 March 2021.