Part 3: How well is public accountability positioned for the future?

3.1

Although our current system has served the public sector well, increased public expectations and public sector reforms provide an imperative and an important opportunity to consider whether improvements can be made.

3.2

This Part draws on interviews with senior public sector leaders, as well as other research to discuss how well positioned the current public accountability system is to meet the public's increased expectations.

3.3

In our view, achieving effective public accountability relies on five essential steps:

- developing well-informed relationships;

- setting clear objectives;

- agreeing meaningful, appropriate, and accessible information;

- establishing the right forums for discussion and debate; and

- agreeing a set of relevant consequences that encourage the right behaviours.

Are there well-informed relationships?

3.4

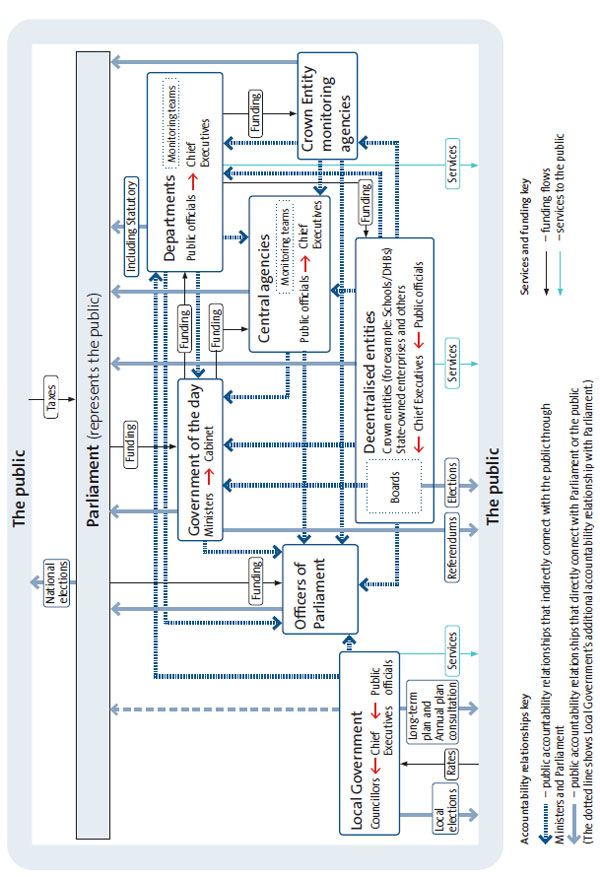

Our current public accountability system is derived from our constitutional arrangements and is based on the United Kingdom's Westminster "chain" of accountability (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

The Westminster chain of accountability

Source: Adapted from: Stanbury, W (2003), Accountability to citizens in the Westminster model of government: More myth than reality; Roy, J (2008), "Beyond Westminster governance: Bringing politics and public service into the networked era"; and State Services Commission (1999), "Improving accountability: Setting the scene".

3.5

Figure 4 shows that the chain of accountability starts with the public official's accountability to their chief executive and ends with Parliament's accountability to the public. The chain provides a clear set of well-defined accountability relationships for holding to account those responsible for delivering public services that:

- are controllable through individual organisations;

- are easily and clearly defined; and

- have few external influences.

A complex network of accountability relationships

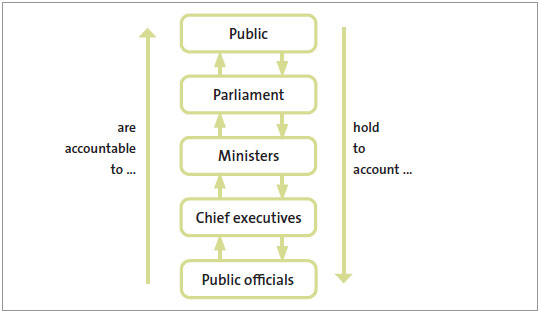

3.6

As the management and delivery of public services and outcomes have expanded and changed over the last few decades, the traditional chain of accountability has become increasingly complicated with lots of moving parts. It has also become more complex; that is it involves many inter-relationships that can be difficult to understand and predict. New and different ways of organising, funding, delivering, governing, and monitoring public services have contributed to this. Figure 5 shows the various accountability relationships in the public sector today. The larger arrows in Figure 5 show which organisation is accountable to which.

3.7

Figure 5 also shows the complexity of these accountability relationships. Taken as a whole, it is a somewhat entangled network of multiple institutions, roles, relationships, and expectations. For example, decentralised public organisations (such as universities, district health boards, and schools) have many different accountability relationships, including relationships with their chief executives and Boards. Each of these accountability relationships have different objectives, expectations, information, forums for debate, and consequences.

3.8

Gill, in discussing specific relationships between Ministers, the State Services Commissioner, and chief executives in 2011, also observed a:

… far more complex reality than a simple principal-agent model … it suggests a world of multiple principals, with ministers facing different imperatives from departmental chief executives.33

Figure 5

Mapping the public accountability system

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

3.9

Because of the public accountability system's Westminster origins, there is a strong emphasis on indirect lines of accountability to the public through Parliament. Many of these lines are based on how funding is allocated to appropriations rather than on how and to whom public services are delivered. Local government has a more direct accountability relationship with its communities. Even so, local government operates within the legislative and regulatory framework established and maintained by Parliament.

3.10

Although Figure 5 is complex, it still does not include:

- the accountability relationships related to te Tiriti o Waitangi;

- the many other accountability relationships with related organisations and institutions, including the judiciary, the media, the New Zealand Police, the Serious Fraud Office, subsidiaries, council-controlled organisations, departmental agencies, the Head of State, professional institutions, international institutions, and the private/non-governmental organisation sector;

- collaborative working arrangements between public organisations, such as the Joint Venture for Family Violence and Sexual Violence;

- information transfer mechanisms, such as the Official Information Act 1982, reporting, and complaints; and

- informal or as-required relationships that arise from time to time (for example, public sector consultations about proposed policies with the public).

Relationships are not well understood and are challenging

3.11

Many public sector workers we spoke to found their accountability relationships complicated and disjointed. One person said, "I don't think public servants are held to account in any logical fashion". Another said, "[t]he system … is clunky, it is siloed … from out there it appears that there is no talking between the parties".

3.12

Many of those who worked outside of Wellington, including in local government, did not feel they had a constructive or informed accountability relationship with central government. One person said, when talking about complying with central government accountability requirements, "there's so many branches of government and parts of this organisation are effectively accountable to different parts … the government is like this great hydra". Another person said, "I think Wellington just blocks … every inch of the way". Many who worked in regional areas of New Zealand considered their accountability relationship was primarily with their communities. They took pride in maintaining strong local community ties.

3.13

For some, the rigid public accountability processes were a barrier to collaborative relationships and adaptability. When talking about the public accountability system's ability to respond to community needs, one person said "it can't be a cruise liner with a one-size-fits-all, there has to be, in my view, some adaptability but it's very, very hard to break that model.". Another person said, "we continue to say … the community needs to change to fit the system as opposed to … this system isn't actually working".

3.14

Several people we interviewed observed that Māori still lacked representation in the public sector, particularly in local government. Recent legislative changes have made it easier for councils to establish Māori wards34 to encourage greater Māori participation in local government.

3.15

When talking about the Māori/Crown relationship, it was described as based more on the specific rights from Te Tiriti o Waitangi rather than the partnership that underlies it. One person said "[t]he Westminster approach is not aligned with the Māori approach to accountability – for Māori it is about the relationship not the rights".

3.16

Other research has highlighted sometimes uninformed and difficult relationships across the public sector. For example, in 2020 the New Zealand Productivity Commission (the Productivity Commission) reported on the many insights it had from inquiries into local government. One of the report's observations was:

A recurrent theme across the Commission's inquiries has been the poor state of relations between central and local government. This failure arises from a lack of understanding of each other's roles and of the constitutional status of local government.35

3.17

The findings from interviews carried out by the Productivity Commission in 2017 also highlighted the value of developing collaborative, rather than adversarial, relationships. Collaborative relationships were seen as more effective in holding organisations to account for their performance in the state sector.36

3.18

Some public officials we interviewed identified challenges to building informed relationships with the public. These included:

- some of what the public sector does is complicated to explain;

- the public sector cannot always meet everyone's needs;

- there might be privacy or security implications regarding some information;

- some expectations might be more important than others; and

- the public can be ill-informed or uninterested.

3.19

These challenges need to be considered. However, care is needed to avoid what researchers have referred to as "a vicious circle in accountability". This is where, particularly in complex or high-risk situations, "the lack of public participation is justified by the lack of competence, and the lack of competence is perpetuated by the lack of participation".37

3.20

For many people, the relationships that underpin effective public accountability do not appear to be well established, maintained, or informed. At times, they also lack proper community representation and can be confusing and fragmented. Given the complexity of the public accountability system and the multiple (and sometimes conflicting) accountability arrangements and expectations involved (see Figure 5), this is not surprising.

3.21

The people we interviewed suggested some improvements, including focusing on what communities want and building better relationships between central and local government.

Are there clear objectives?

3.22

Everyone we interviewed who worked in the public sector recognised public accountability as a fundamental part of what they do. However, there was less clarity and consistency in the responses about why they think public accountability is important.

There is a lack of understanding about the public accountability system

3.23

People we interviewed considered being accountable to the public as a privilege. They also identified many strengths in the public accountability system, including good budgetary and financial controls, accrual accounting, strong checks and balances, and good public consultation at the local government level.

3.24

However, one-third of the people we interviewed who worked in the public accountability system said they did not have a clear understanding of it. Of the people who said they understood the system and its objectives, many explained it in a narrow way and focused on what it meant to their own individual roles and responsibilities.

3.25

One person said, "[w]e seem to have lost what accountability means and if you lose that, and I mean lose it with the public … no one believes you anymore". Another said:

It is impossible to measure good performance or behaviour across the system because of the woolly definition of public accountability. I don't think anyone really knows what it means.

There is little agreement about the purpose of public accountability

3.26

People we interviewed who worked in Wellington said the purpose of public accountability was largely about delivering better services, outcomes, and oversight. Many of them said that public accountability was important for improving public sector performance and parliamentary scrutiny. Therefore, they talked a lot about information, forums for debate, financial performance, and service delivery. One person talked about a strong accountability focus on financial performance, funding, and control, noting that "in terms of short-term delivery and accounting for the money and resources we have some really good accountability mechanisms".

3.27

Many of the people we interviewed who worked outside of Wellington had a different perspective. They talked more about public accountability as fundamental to developing and maintaining good relationships with their communities and other regional bodies. Therefore, they talked about the importance of behaviour, maintaining a good reputation, and ensuring that moral and ethical matters were well managed.

3.28

One person said that, for Māori, there were two main purposes:

[O]ne is obviously for your financial governance [and] management, getting outcomes. But there is also that accountability that you have to front … to your people to account for your overall stewardship of your role, not just the money.

3.29

When we asked who public officials are accountable to, we received a variety of answers. These included Parliament, the public, particular communities, Ministers, central government departments, and Boards. One person said, "everyone actually!"

3.30

There was little evidence of a clear and common understanding of public accountability, why it was important, and who it was for. Given the complexity of the public accountability system, this is not surprising. This lack of a common understanding might also explain why three-quarters of the people we interviewed who worked in the public accountability system thought the way the public sector is held accountable was not working as well as it could.

3.31

Although various objectives were discussed, many were specific to people's roles. The people we interviewed were not always clear or confident about what the public accountability system was intended to achieve. This was sometimes the source of confusion about respective roles and responsibilities for accountability arrangements across the system. Some people we interviewed suggested there could be improvements to public accountability. However, people did also stress that it was important to maintain the system's strengths, such as strong financial controls.

Is the information used appropriate?

3.32

The people we interviewed spoke extensively about public accountability information. Many public sector workers felt that the accountability information they were asked to provide was not appropriate for different audiences or relevant in explaining what they did and the difference they were making.

3.33

People talked about having to provide information only once a year and that it was too complex, mainly quantitative, and not always focused on services or outcomes. One person said, "financial information … [is important] … but I think there are some pretty huge gaps in terms of ethics and conduct". Another person thought that performance measures were used mainly to support what management wanted and not what readers of the information wanted, saying "departments use performance measures … for support not illumination".

3.34

Many people we interviewed from regional New Zealand questioned the relevance and importance of accountability information requested by central government. One person said, "they're doing 10 reports a day for one kid … what is being done with all these reports?"

3.35

What people said to us about the appropriateness of accountability information is consistent with other research, including:

- our survey results (see Part 2), which showed that in order to be more accessible and relevant, accountability information needs to consider the views of the different communities receiving it;

- interviews carried out by the Productivity Commission in 2017, which observed that:

… accountability and performance requirements administered by central agencies are excessive … [and while] … designed with the intention of driving better performance, the requirements too often imposed excessive compliance costs for little benefit;38

- a 2019 report by the Productivity Commission, which found that:

… the current performance-reporting requirements on local authorities, including the financial and non-financial information disclosures, are excessively detailed, inappropriately focused and not fit for purpose;39 and

- our 2019 report on councils' long-term plans, where we described council long-term plans as "long and complex". We suggested a review of the content of long-term plans should be carried out "to ensure that they remain fit for purpose as planning and accountability documents".40

3.36

Furthermore, in our work on improving performance reporting, we show that reported performance information is not always properly explained or used appropriately.41

3.37

Although the comments in our interviews were varied, they collectively revealed a general sense of concern about the extent, relevance, and usefulness of accountability information. One possible reason for this, is the lack of clear and common objectives for public accountability across the public sector.

3.38

Many people we interviewed said there should be a greater focus on information about what is achieved with public money across sectors and the whole of government.

Are there the right mechanisms or forums for discussion and debate?

3.39

Most people we interviewed recognised that a public organisation's annual report was the main way of carrying out its public accountability obligations. However, many also saw annual reports as compliance driven, not convenient or accessible, and did not easily support public feedback or debate. People spoke about annual reports as being overly technical and difficult to understand. One person, talking about the relevance of these documents noted, "one size does not fit all". This was a common view.

3.40

Dormer and Ward, in researching accountability and public governance in New Zealand, observed that:

… governments, and individual government agencies, often publish significant amounts of information that is neither read nor understood by those to whom they are accountable.42

3.41

The people we interviewed who work in central government said Parliament and select committees were important forums for public accountability. However, some also noted that members of Parliament did not always have enough time or resources, or access to the right skills and advice. One person who attended select committees said "I think we get challenged … but I am not sure we get challenged in the right way."

3.42

These comments about select committees were consistent with other research on improving long-term governance in Parliament. Researchers have found "important aspects of the existing parliamentary scrutiny arrangements are inadequate".43 The 2020 report from the Standing Orders Committee also referred to data that suggests the number of inquiries initiated by select committees has been trending downwards for at least the last 10 years. The report noted that "subject Select Committees are not scrutinising the Government to the extent expected, and thus are not entirely fulfilling their purpose".44

3.43

During our interviews, various comments were made about the effectiveness of the Official Information Act 1982 as a mechanism for transparency. Some viewed this as a strong mechanism while others saw it as weak. There was a similar difference of opinion about the use of social media. Some consider social media a positive opportunity and others consider it an undesirable challenge. There was a general view that the relationship between public officials and the media could at times be problematic.

3.44

Some of the people we interviewed who worked outside Wellington mentioned using different and more direct approaches to demonstrating accountability to the public. These included, for example, road-shows and other more tailored reporting. One person working in the education sector said that because reporting to parents was not meeting their needs, they worked with parents, through newsletters, meetings, and surveys, to create a new reporting approach that "revamped the report form based on [what] these parents wanted and … to me that's accountable".

3.45

There were many comments about the approaches used to communicate accountability information and whether these approaches encouraged the right level of discussion and debate. People we interviewed found that complying with one-size-fits-all accountability requirements, such as annual reports, meant they were not always relevant or well understood. People, particularly those who worked outside Wellington, were exploring other more direct and tailored approaches to presenting and discussing what they did.

3.46

Suggested improvements from those interviewed included being more transparent about what went well and what did not, and using different ways to communicate.

Are the judgements and consequences appropriate?

3.47

There were relatively few comments in our interviews about the judgements and consequences in accountability relationships. For people who did comment on this, consequences were seen as an important part of achieving the objectives of public accountability. Some people commented that consequences were at times unclear and inconsistently applied. Others said that, to be useful, consequences needed to be meaningful and relevant. One person said, "we have got to have some real sanctions and they have got … to be meaningful".

3.48

Much of the research about consequences and public accountability discusses two things:

- punishment after an event has occurred; and

- motivation or stimulus before an event has occurred.

3.49

Deciding on the appropriate type of consequence usually depends on the level of trust between the account holder and account giver and the objectives of the accountability arrangement. Choosing the wrong type of consequence can be significant. It can lead to a lack of openness, poor decision-making, and a culture of risk aversion and blame.

3.50

Interviews carried out by the Productivity Commission in 2017 noted one state sector leader as saying:

Accountability and performance requirements are generating "hard" performance measures … but there are no consequences for good or bad performance against those measures.

3.51

People interviewed by the Productivity Commission indicated that those with monitoring responsibilities were often too quick to take a punitive approach, which created an adversarial rather than collaborative relationship. The Productivity Commission also observed that:

… many interviewees spoke of enforcement too often being undertaken by staff who lacked the needed experience and skills, who applied a tick box, one-size-fits-all approach, and who sought to "catch out" and punish state entities. There tended to be a presumption of bad faith held by central agencies with respect to the behaviour of agencies.45

3.52

The findings reinforce the importance of having appropriate consequences to any public accountability relationship and to the overall culture of an organisation. However, in practice, it appears little attention is given to the right consequences. At present, they remain largely punitive and, at times, can be inconsistently applied.

3.53

In the next Part, we consider how the public accountability system could change to better meet Parliament and the public's needs.

33: Gill, D, et al (2011), The Iron Cage Recreated: The performance management of state organisations in New Zealand, Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, page 107.

34: Māori wards and constituencies establish areas where only those on the Māori electoral roll can vote for the representatives.

35: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2020), Local Government Insights, page 14, at productivity.govt.nz.

36: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2017), Efficiency and Performance in the New Zealand State Sector: Reflections of Senior State Sector Leaders, page 14, at productivity.govt.nz.

37: Kerveillant, M and Lorino, P (2020), "Dialogical and situated accountability to the public. The reporting of nuclear incidents" Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, page 3.

38: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2017), Efficiency and Performance in the New Zealand State Sector: Reflections of Senior State Sector Leaders, page 19, at productivity.govt.nz.

39: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2019), Local Government Funding and Financing, page 112, at productivity.govt.nz.

40: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans.

41: Office of the Auditor-General (forthcoming), The problems, progress, and potential of performance reporting.

42: Dormer, R, and Ward, S (2018), Accountability and public governance in New Zealand, unpublished research paper.

43: Boston J, Bagnall, D, and Barry, A (2019), Foresight, insight and oversight: Enhancing long-term governance through better parliamentary scrutiny, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, page 12.

44: Standing Orders Committee (2020), Review of Standing Orders 2020: Report of the Standing Orders Committee, pages 21 and 22, at parliament.nz.

45: New Zealand Productivity Commission (2017), Efficiency and Performance in the New Zealand State Sector: Reflections of Senior State Sector Leaders, pages 14, 19, 20, and 42, at productivity.govt.nz.