Part 2: Paying to use private rental properties as emergency housing

2.1

In this Part, we describe:

- the emergency housing grant and how it has changed since 2016;

- the Ministry's decision to start paying to use private rental properties as emergency housing; and

- what happened when the Ministry decided to stop using private rental properties as emergency housing.

What the Emergency Housing Special Needs Grant is

2.2

The Ministry is responsible for implementing several programmes that are intended to help people in need. One of these programmes is the Special Needs Grant Programme (the programme).10 The programme provides "non-taxable, one-off recoverable or non-recoverable financial assistance to clients to meet immediate needs".11

2.3

The emergency housing grant is part of the programme and was established in 2016.12 It is defined as "a grant to an applicant for the supply of Emergency Housing that MSD considers adequate to meet the needs of the applicant and their immediate family".13

2.4

The emergency housing grant was intended as a last resort to pay for a week or two of temporary accommodation until a person could find longer-term accommodation.

2.5

Initially, the emergency housing grant paid for commercial accommodation such as motels or hostels.

2.6

The Work and Income website defines emergency housing as:

… premises that are intended to be used as temporary accommodation by people who have no usual place of residence or who are unable to stay in their usual place of residence (whether also used as temporary accommodation by other people).14

2.7

The Ministry's service delivery staff, including case managers, have authority to approve grants within the limit that the programme specifies.15 The programme states that the amount paid for emergency housing cannot cost more than the "actual and reasonable costs" of the emergency housing, including any security bond.

2.8

The Work and Income website includes guidelines for Ministry staff on the maximum payment rates for hostels and motels. The guidelines allow for a maximum payment of $40 each night for a single person and a maximum payment of $260 each night for a family of four or more.

2.9

The guidelines allow staff to pay higher rates in some circumstances. These include if there is a lack of adequate accommodation to meet the needs of a person and their family, or if the person has particular needs such as wheelchair access.

2.10

In a briefing to the Minister dated 20 August 2020, the Ministry noted that Ministry staff have the discretion to approve grants that are more than the maximum limits in exceptional circumstances. This could be, for example, when there is no alternative accommodation.

2.11

The Ministry said that, in all instances, its focus is on "ensuring our clients are able to access warm, safe and dry emergency housing".

The relationship between the Ministry and the supplier of emergency housing

2.12

The Ministry's position is that it has no contractual relationship with suppliers of emergency housing. The Ministry considers that it is paying the grant to the supplier on behalf of the person needing emergency housing.16

2.13

The Ministry sees its role as ensuring that people have the "financial resource to access emergency housing", and it has no function for checking the housing's quality. We discuss the Ministry's view in paragraphs 3.51-3.61.

2.14

This is consistent with the way the Ministry says that it funds other essential or emergency needs. For example, although the Ministry provides a special needs grant for food, it is not responsible for ensuring that the food purchased is good value or of reasonable quality. The person receiving the grant selects the good or service (within some limits). They also retain their rights under consumer law and can seek redress from the shop if a product is faulty in some way.

2.15

In a briefing to the Minister of Social Development on strengthening processes for the emergency housing grant dated 20 September 2020, the Ministry described the process:

Eligible clients are able to identify their preferred emergency housing accommodation that will work best for them (eg based on proximity to work, schools and childcare). When clients have not identified emergency housing accommodation, [the Ministry] works with the client to identify an appropriate supplier based on the above criteria. Once an emergency housing supplier is identified, [the Ministry] will then pay the supplier (via [an emergency housing grant]) on behalf of the client.17

How the emergency housing grant process works

2.16

A person who has nowhere to stay can apply for the emergency housing grant. They need to talk to a case manager from the Ministry, who can approve the emergency housing grant if they are satisfied that the person meets the criteria.18

2.17

When a person arrives at a Ministry office looking for emergency housing, staff call suppliers to find appropriate accommodation and establish how much it will cost.19 They also agree the amount of any security deposit to hold in case of damage with the supplier.20 The amounts are recorded on the Ministry's systems as being paid by the emergency housing grant.

2.18

The Ministry told us that staff look for accommodation if the client does not have a preferred option. However, the evidence we saw suggests that clients were discouraged from sourcing their own private rental properties.

2.19

The Ministry normally pays emergency housing suppliers directly. However, if a supplier has EFTPOS and can accept a Work and Income New Zealand payment card, the client staying in the emergency housing can pay for it that way. If the Ministry pays the supplier through direct credit, the supplier provides an invoice that the Ministry matches with the pre-approved amount before paying.

2.20

The client is given the address of the accommodation to go to. The initial emergency housing grant covers a maximum of seven days. If, after seven days, the client has been unable to find alternative accommodation and needs an extension of the emergency housing grant payment, they need to contact their case manager and show evidence that they have been actively looking for longer-term accommodation.

2.21

Ministry staff told us that this means evidence of attending viewings for rentals and applying for tenancies. Before New Zealand went into Alert Level 4 lockdown in March 2020, people were required to visit a Ministry office to see their case manager. Now they can call the Ministry.

2.22

The emergency housing grant can be renewed for up to seven more days each time a client applies.21 There is provision for grants to be renewed for up to 21 days if the Ministry has allocated an intensive case manager to the person.22

2.23

Ministry staff we interviewed talked about the challenges in finding affordable housing some people faced. Ministry staff told us that, in a competitive market where demand for low-cost rentals exceeded supply, people with high levels of debt, larger households, people with a history in the tenancy tribunal, and beneficiaries were less likely to be successful than other applicants when applying for tenancies.

2.24

Ministry staff noted that the search was demoralising and hopeless for some people. However, they were still required to provide evidence that they were actively looking for housing.23

2.25

The intention was for people to stay in emergency housing for one or two weeks. However, Ministry staff told us that the challenges in securing alternative accommodation meant that people often stayed in emergency housing, including private rental properties, for weeks or even months.

How the emergency housing grant fits with other housing support

2.26

The emergency housing grant is intended to be a last resort option. The other publicly funded longer-term housing options include transitional housing, public housing through Kāinga Ora and community housing providers, and support for people in private rental properties.

2.27

Transitional housing is a 12-week housing programme. People eligible for transitional housing are placed in housing and provided with support, such as budgeting advice. Although the Ministry completes assessments for public housing and refers people to transitional housing providers, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development procures the contracts between the Ministry and suppliers for transitional and public housing.

2.28

The Ministry also helps people find long-term accommodation through property brokers. The property broker role was established in early 2020.24 The Ministry employs them to find private rental properties and negotiate with landlords to make their properties available for the long term.

2.29

The Ministry also has several ways it can help people moving into private rental properties, including payments to cover bond and rent, accommodation supplements, and temporary additional support.

Why the Ministry of Social Development decided to use private rental properties as emergency housing

Increasing demand for emergency housing

2.30

In 2017, there was increasing pressure on the rental housing market in Auckland. The Ministry says that there was also pressure on the short-term accommodation market, with high demand from tourism and international students at the same time. Although the transitional housing programme had started, supply was not keeping up with demand.

2.31

Frontline staff told us that, in November 2017, they were dealing with increasing numbers of large households looking for somewhere to live. Ministry staff told us that most of the households were Māori or Pacific families.25

2.32

These households did not have access to longer-term accommodation straight away. Frontline staff described the difficulties that they had finding appropriate motels for them.

2.33

One of the challenges for large households was that motels generally could not fit everyone in one room. Households had to be split between motel rooms, which meant an adult had to be available to supervise children in each room. That was not always possible for larger or single-parent households.

2.34

Ministry staff also described the difficulties some disabled people had with finding suitable emergency accommodation.26 In particular, there was a shortage of suitable motel rooms for people in wheelchairs.

2.35

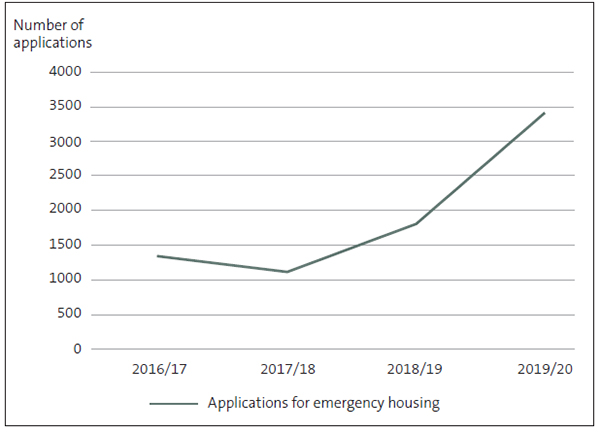

Figure 1 shows that, from mid-2018, the number of people looking for emergency housing continued to increase in Auckland. This put pressure on Ministry staff to find accommodation quickly. Frontline staff told us people often arrived at their offices late in the day needing somewhere to stay that evening.

Figure 1

The number of applications for emergency housing in Auckland, 2016/17-2019/20

Source: The Ministry of Social Development. Note that applications may cover families that include adults and children. The dates reflect the 1 July to 30 June year.

How the Ministry of Social Development started using private rental properties as emergency housing

2.36

The Ministry started using private rental properties as emergency housing in November 2017. A family had been placed in a motel that the emergency housing grant paid for.

2.37

However, the motel room was crowded, so the family looked for a better short-term option. They found a house through an online short-term accommodation booking service. The house was more suitable and cheaper than the motel they were in.

2.38

The family went to a Ministry office and asked whether the Ministry could use the emergency housing grant to pay for the private rental. Frontline staff told the family that the Ministry could use the grant in this way.

2.39

A property management company managed this house. The property management company subsequently registered as a supplier for the Ministry in November 2017. It then made more houses available for the Ministry to use as emergency housing.

2.40

Ministry staff told us that having houses available for large households was a "miracle" because it meant households that could not stay in motels had a place to go.

2.41

The property management company emailed Ministry staff with properties it had available, how many people the property could house, and the weekly cost. Ministry staff could also contact the property management company when people arrived at its offices looking for emergency housing.

2.42

Ministry staff told us that the property management company was generally able to find a property.

2.43

The Ministry said that it implemented some parameters to manage the use of private rental properties – for example, only using these properties for large families and people with mobility or social functioning issues. However, it did not develop a policy on using private rental properties as emergency housing or change its guidance for staff.

2.44

As the practice of using private rental properties as emergency housing increased, so did the number of suppliers offering their properties. By the time the Ministry stopped paying for private rental properties, 21 suppliers were registered with it.

2.45

Although private rental properties were primarily used as emergency housing to accommodate larger households, they were also sometimes used for smaller households and individuals. For much of the period covered by this inquiry, the Ministry was able to report on how many individual emergency housing grants were granted, but it could not accurately report on the size of the households using these grants. This meant that the Ministry could not say how many people were living in emergency housing.

2.46

However, in May 2020, the Ministry improved how it collected data. It says that it can now report on the size of a household and how many people, including children, were living in emergency housing at any point in time after May 2020.

2.47

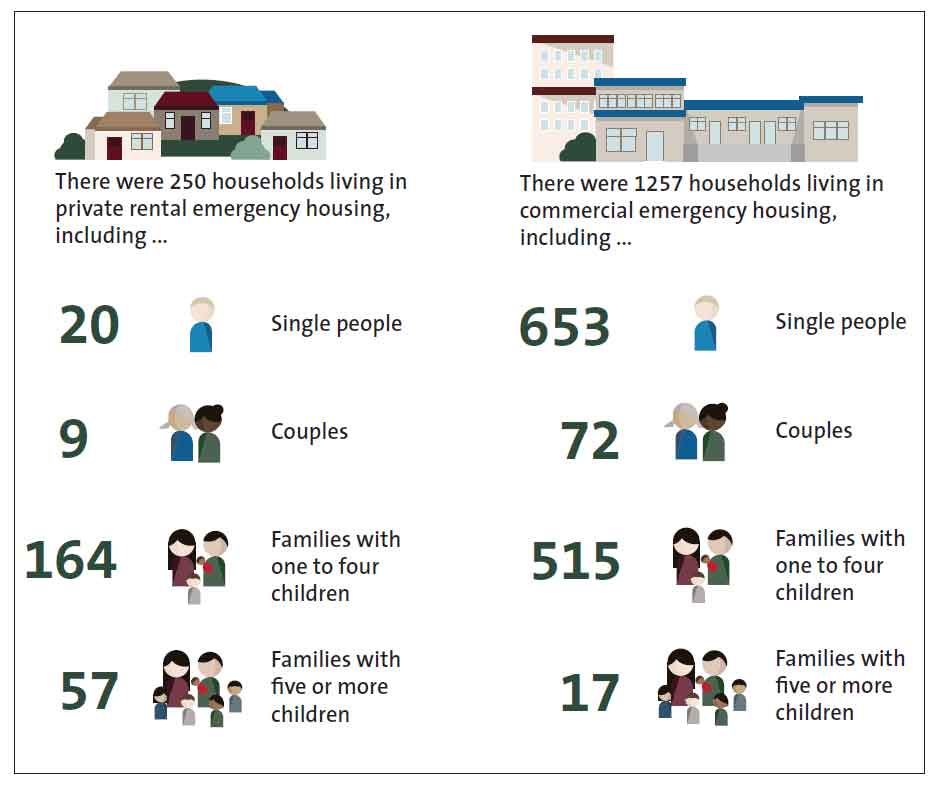

The Ministry provided us with data for the households in emergency housing in Auckland, as at 29 May 2020.27 Figure 2 shows the households in emergency housing on that day.

Figure 2

The number of people in Auckland living in private emergency housing compared with people in Auckland living in commercial emergency housing, as at 29 May 2020

Source: The Ministry of Social Development.

Suppliers of the private rental properties

2.48

The Ministry understood that the first property management company it used was preparing houses for sale while also making them available as short-term accommodation to bring in some income for the owner.

2.49

In April 2019, the Ministry spoke to the owner of the property management company about their business. The owner said that it managed properties as holiday rentals. Some of those houses were on the market for sale, and families using them as emergency housing had to vacate for any open homes.

2.50

In 2021, the property management company went into liquidation. The liquidator reported that one of the reasons the company became insolvent was because, after the Ministry stopped paying for private rental properties, it could no longer pay the long-term leases that it had entered into with landlords. Therefore, it appears that these properties were available to the supplier on long-term leases.

2.51

Some suppliers leased houses and sublet them as emergency housing. Other suppliers were property management companies that charged property owners a fee.

2.52

One supplier told us that their business helped investors buy residential property specifically to make it available as emergency housing. Another supplier told us that the houses it managed were not usually used as long-term rentals but that property owners trusted the supplier to manage their properties as emergency housing.

2.53

Until the Ministry wrote to suppliers in November 2019 (see paragraph 2.88) we did not find explicit expectations that properties needed to be furnished (including bedding) or needed electricity and gas (if applicable). However, the suppliers we spoke to said that they provided fully furnished properties. One supplier we spoke to said that they also included internet.

Becoming a supplier

2.54

Suppliers must register with the Ministry to receive payment from it. Emergency housing suppliers had to complete the Ministry's standard registration process for suppliers of goods and services.

2.55

Before September 2019, suppliers had to complete an online form and provide their bank account details to the Ministry. The form asked them to identify what they were supplying. Only one paragraph in the form referred to the quality of the good or service being supplied:

I/We will ensure that Ministry clients know that I am/we are responsible for any fault with the product or service delivered, including standard warranty/guarantee conditions listed under the Consumer Guarantees Act 1993.28

2.56

From September 2019, Ministry staff were required to check that the person or business registering as a housing supplier was either the property owner or had authority to act on the owner's behalf. This was almost two years after the Ministry started to fund private rental properties.

2.57

If the applicant was a property management company or property manager, staff also needed to check that they had a contract with the property owner. Although this requirement applied when the supplier registered, the Ministry did not require suppliers to provide evidence that they had the authority to rent out new properties after the initial registration (see paragraphs 2.72-2.77 and paragraph 3.56).

2.58

Apart from one supplier, the Ministry did not check whether suppliers that registered before September 2019 had authority to deal with the houses they provided. The Ministry told us that:

…the monitoring and enforcement of regulations around sub-letting are the responsibilities of other agencies and … that it has voluntarily strengthened its systems to improve the services it delivers to its clients rather than because it has a legal responsibility to do so.

2.59

The Ministry's verbal or email agreement with suppliers covered the period of the emergency housing grant.29 The Ministry told us that it makes agreements with suppliers on its clients' behalf.

Responsibility for the quality of emergency housing

2.60

The Ministry told us that it was paying grants to the suppliers on behalf of the people needing emergency housing but that it had no contractual arrangement with the suppliers. Accordingly, although the Ministry told us that it expected suppliers to meet standards in the Residential Tenancies Act 1986 and other relevant legislation, it did not set any standards or monitor compliance with legislative and regulatory requirements. We comment on this in paragraphs 3.53-3.61.

2.61

In the Ministry's view, it had no inspection function for quality standards or legal right to access the properties. The Ministry also told us that its staff were not trained to identify issues with housing quality. The only way of knowing whether there was an issue with a property was if a person living in emergency housing contacted the Ministry to make a complaint.

2.62

The Ministry told us that the registration process does not involve an assessment of the quality of the goods or services. It expects that suppliers will be subject to "a range of monitoring regimes".30

Payments to suppliers

2.63

From 1 January 2018 to 30 June 2020, the Ministry paid about $37 million to suppliers to use private rental properties as emergency housing in Auckland.31

Why the Ministry of Social Development decided to stop using private rental properties as emergency housing

Condition of the properties

2.64

Ministry staff and an advocate for people in emergency housing told us that there were issues with the quality of some of the private rental properties that the emergency housing grant paid for. The Ministry provided us with emails and photos about concerns people had raised.

2.65

The Ministry also described six complaints that it had recorded formally.32 Ministry staff told us that, when they raised concerns with suppliers, either the problems were solved or the people living at the property were moved.

2.66

However, Ministry staff did not routinely keep records of all complaints or photos.33 Although there was a spreadsheet for recording complaints, it included only two entries for suppliers of private rental properties in Auckland between April 2019 and December 2020.

2.67

The advocate we spoke to said that some of the private rental properties used as emergency housing were not fit for purpose. He saw houses that were like building sites with debris inside and outside, and houses with no ovens, furnishings, or bedding.

2.68

The advocate told us that, in many instances, families were so desperate they would take anything. He told us that he sometimes accompanied people to emergency housing as part of his advocacy. The addresses he went to were for private rental properties the Ministry had funded as emergency housing. He considered that six to 10 places he saw were not fit for purpose, and he advised people not to move into them.

2.69

In September 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development received a complaint about a house that three families occupied and that was funded through emergency housing grants. The house had a leaking roof and was overcrowded. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development forwarded the complaint to the Ministry.34

2.70

We were unable to obtain a complete list of private rental properties used as emergency housing. However, some private rental properties in the sample we looked at housed more than one family. These private rental properties were sometimes described as having a "front property" and a "back property".

2.71

To be recognised as separate dwellings, both the front and back properties need to be recorded in council records as dwellings, and the council should have consented them for use as dwellings. However, we checked the Auckland Council records, and there was no consent for a second dwelling on three of the properties we checked.

Legality of subletting

2.72

As well as complaints about the condition of the property, issues were raised about the legality of some of the suppliers' tenancy arrangements. Several suppliers leased houses and sublet them as emergency housing.

2.73

In a Tenancy Tribunal decision dated 24 May 2019, one of the suppliers was found to have breached the tenancy agreement when he sublet the property as emergency housing to the Ministry for 16 weeks. The tenancy agreement did not allow subletting without the landlord's consent, which had not been given.

2.74

The Ministry had paid the supplier $60,800 ($3,800 each week) through the emergency housing grant. The rent the supplier paid to the landlord under the lease for the same 16-week period was $8,000 ($500 each week).

2.75

It was not possible for us or the Ministry to identify whether any other suppliers were offering properties to the Ministry without the property owner's authority. This was because the Ministry did not have systems to ensure that suppliers of individual properties used as emergency housing had the property owner's authority.

2.76

The Ministry told us that it had no obligation to determine the nature of the lease arrangements between property managers and property owners. However, it told us that it changed its registration process in 2019 to make clear its expectation that the lessee had the owner's permission to use the property as emergency housing.

2.77

The Ministry noted that Tenancy Services is responsible for monitoring and enforcing issues with subletting residential properties.

Effect on transitional housing and the long-term rental market

2.78

In September 2019, two suppliers of transitional and community housing contacted the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. They were concerned that suppliers were providing private rental properties as emergency housing instead of as longer-term housing because of the high rates the Ministry was paying.

2.79

This could reduce housing supply for people needing transitional housing or more permanent housing, particularly because the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development would usually only pay the market rent and would not compete with the amounts the Ministry was paying.35

2.80

For example, a house had been leased for public housing for $1,400 a week. When the lease ended on 18 September 2019, the owner did not renew it. They made it available as emergency housing instead. The family who had been living in the house had to move.

2.81

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development raised these concerns with the Ministry. The Ministry talked to one supplier that it understood had the property available as emergency housing. The supplier said that the property was being redeveloped and was not available long term.

2.82

However, on 4 November 2019, a different supplier offered the same property to Ministry staff as emergency housing for $3,900 a week. This supplier told us that it had leased the property.

The Ministry's response to the issues

2.83

Between September and November 2019, the Ministry worked with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development on the issues that had been raised and how to respond. In November 2019, it agreed on a two-stage response.

2.84

The Ministry would first send a letter to suppliers asking them to consider long-term leases or to become transitional housing suppliers. The Ministry would then contact specific suppliers that had taken their properties off the long-term rental market to use them as emergency housing.

2.85

The Ministry hoped that this would reduce the use of private rental properties as emergency housing and minimise any adverse effect on the availability of long-term rental properties.

2.86

The Ministry considered setting up a service-level agreement between it and suppliers. The purpose of such an agreement would be to reflect the level of service the Ministry expected and provide a mechanism for controlling costs.

2.87

However, the Ministry did not end up progressing the idea of a service-level agreement with suppliers. The Ministry told us:

The Ministry notes that it investigated the option of using a Service Level or similar agreement to better manage the use of private rentals for emergency housing. That option was not progressed for the following reasons:

- it may have seen MSD act outside legislation by using a hardship grant to ‘underwrite' an agreement,

- it may have exacerbated the risk that suppliers perceived the relationship as a contract,

- it may have led to the replication of transitional housing functions carried out by HUD, and

- it likely would not have addressed concerns on the impact on the private rental market.

2.88

In November 2019, the Ministry wrote to the suppliers setting out its expectations that suppliers would be:

- Compliant with the Residential Tenancies Act (1986) and the Residential Tenancies (Healthy Homes Standards) Regulations (2019). It is important to note there may be potential risks to your business if you are found to be acting in a manner inconsistent with the RTA.

- Providing emergency housing that includes the required chattels for such accommodation i.e. heater, bedding, linen, cooking facilities etc.

- Not impacting the housing market by reducing the supply of long-term rental properties in the Auckland market.

- Not marketing to existing landlords with tenanted properties by offering higher returns from Emergency Housing.

- Mak[ing] properties available on request for inspection by the Ministry.

- Not marketing or using Emergency Housing to trial a tenant's suitability for more permanent housing.

- Not directly marketing vacancies to MSD case managers. Our preference would be to establish a centralised contact point, so we can ensure the right households are placed in your properties, and so we can minimise any unintended consequences of our utilisation.

2.89

The number of private rental properties used as emergency housing did not decrease. The Ministry estimated that, in September 2019, 23% of Auckland households in emergency housing were in private rental properties. By the end of March 2020, this increased to 31%.

2.90

One of the reasons the Ministry continued to use private rental properties was because there was a shortage of suitable and affordable alternative housing for people to live in. This shortage continued despite the increase in supply of transitional and public housing.

2.91

Between December 2017 and June 2021, the number of public housing tenancies in Auckland increased by 4298 and the number of transitional housing places increased by 1256. Nevertheless, demand for emergency housing in Auckland continued to grow.

2.92

However, when the country's borders closed because of Covid-19, more motels and hotels became available. This included apartment-style hotel accommodation that was better suited for larger households.

2.93

In May 2020, the Ministry wrote to suppliers telling them that it would stop paying for private rental properties from 30 June 2020.

2.94

Suppliers were invited to consider providing long-term tenancy agreements or to contact the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development to see whether their properties could be used as transitional housing.36

2.95

The Ministry allocated suppliers to specific case managers to help move people to other accommodation. We were told that some moved to emergency housing but that others went into transitional housing, public housing, or private rental properties. Some households could remain in a private rental property on a long-term tenancy agreement.37

2.96

Suppliers we spoke to said that they believed that they were providing a service to the Ministry and the people living in the houses. They said that they saw themselves as filling a gap, both in terms of providing short-term housing and supporting households to find long-term housing.38,39

2.97

We were not able to speak to anyone who was required to leave the private rental properties when the Ministry stopped paying for them. However, we understand that, although the Ministry extended the emergency housing grant week by week, some people had been living in the houses for weeks or even months and regarded the house as their home.

2.98

Based on data the Ministry collected, there were between 633 and 911 children living in private rental properties paid for by the emergency housing grant as at 29 May 2020. We note the timing of the Ministry's decision was not long after the country moved to Alert level 2 on 13 May 2020 and during an ongoing period of change as a result of Covid-19. Ministry staff spoke to the people affected by the decision to move them from private rental properties after it made that decision. However, we did not see any evidence that the Ministry engaged with any representatives of the communities living in emergency housing before deciding to move people back into commercial properties.

10: The Special Needs Grant Programme is one of 29 welfare programmes approved and established by the Minister of Social Development.

11: See workandincome.govt.nz.

12: The Cabinet paper that authorised the creation of the emergency housing grant also authorised the creation of what was to become the transitional housing scheme, where the Ministry procured emergency housing places.

13: See workandincome.govt.nz.

14: See workandincome.govt.nz.

15: Although grants are renewed weekly, some people had multiple renewals and stayed in emergency housing for weeks or months. If people received the emergency housing grant for longer than five weeks, service managers had to approve new grants. Regional directors had to approve grants after nine weeks. The Ministry of Social Development's Deputy Chief Executive had to approve grants after 12 weeks.

16: See the briefing dated 20 September 2020, Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants: Strengthening processes.

17: Briefing dated 20 September 2020, Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants: Strengthening processes, paragraph 4.

18: The Ministry has discretion to grant an emergency housing grant if an applicant has an immediate emergency housing need and not granting an emergency housing grant would have a negative effect on the applicant and their family. See workandincome.govt.nz.

19: The registration process is explained in paragraphs 2.54-2.59.

20: See the Work and Income website, workandincome.govt.nz, for more information about processes.

21: Most people need to renew their emergency housing grant multiple times while they continue to seek long-term housing.

22: The intensive case manager roles were implemented in 2020. Intensive case managers have small case loads and work with clients to find long-term housing. These clients tend to have complex needs, and it is likely they will take some time to find long-term accommodation.

23: This requirement was dropped for Covid-19 Alert Level 4 and 3 lockdown periods. After lockdown, people were able to communicate with the case manager by phone.

24: This was an initiative established under the Aotearoa/New Zealand Homelessness Action Plan. The plan also introduced rental readiness programmes to support clients to access and sustain private rental accommodation.

25: Although the Ministry did not collect specific data about the ethnicity of these clients at the time, Māori and Pacific peoples are disproportionately represented in homelessness data.

26: Staff told us this during interviews. They did not have data to support this, but it is consistent with other data, such as the Homelessness Count, and interviews with other people, such as community groups.

27: The Ministry created this data for internal purposes. It provides a snapshot of the makeup of households in emergency housing shortly before the Ministry stopped funding the use of private rental properties as emergency housing.

28: The form "Retailer/Supplier/Payee Details" is available at workandincome.govt.nz.

29: As we mentioned in paragraph 2.22, this was generally for a period of seven days and up to a maximum of 21 days if the person in emergency housing had an intensive case manager.

30: These include, for example, Tenancy Services or the Council (for consent issues). The Ministry told us that, by contrast, it will scrutinise the quality of the goods and services provided under a "preferred supplier" arrangement when it enters into that arrangement. The Ministry has preferred supplier contracts for whiteware and glasses.

31: We were told that there was limited use of private rental properties in other parts of New Zealand. Most of the spending occurred after November 2018. At this time, the Ministry estimated that only 53 households were placed in private rental properties. This had risen to 224 households by September 2019 and peaked at 356: households in March 2020.

32: It is unclear whether the emails and photos are about these complaints.

33: Ministry staff told us that the Ministry also received complaints from suppliers about the people staying in the private rental properties causing damage or removing items form the house when they left. When the emergency housing grant was set up, the Ministry would also have the person apply for a special needs grant to cover damage or loss. People who received this grant had to repay it.

34: The Ministry did not record this complaint on its spreadsheet of complaints. The Ministry told us that it would not expect to record an issue that a third party raised alongside complaints that its clients raised.

35: The Ministry noted that the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development occasionally exceeds market rents and uses a range of financial and other incentives as part of the overall package to support owners.

36: Two suppliers told us that they had tried to register as a transitional housing provider but had been unsuccessful to date.

37: Information about where the household moved to is in individual client files, and the Ministry had no system to track where people went to when they moved out of emergency housing.

38: These suppliers described a range of assistance they provided, such as social work, financial advice, and training to be good tenants. The suppliers did not have a contract to provide services and told us that they did this because they believed it was the right thing to do.

39: We were unable to obtain data to show how many households were moved from emergency housing into long-term housing.