Part 1: Introduction

1.1

New Zealand’s marine environment covers over 4 million square kilometres of ocean. It includes New Zealand’s exclusive economic zone, which includes the Kermadec Islands and the subantarctic islands. For economic purposes, this marine environment supports the fishing industry, aquaculture, hydrocarbon exploration, extraction of mineral deposits, tourism, and biotechnology. It is also used recreationally by many New Zealanders each year for swimming, fishing, and boating.

1.2

As an island nation, New Zealand’s marine environment serves many purposes and roles, and is a matter of significant cultural, spiritual, and economic importance. To iwi and hapū, water is taonga. The geographic remoteness of the country is also what makes the sea life rich and diverse. Many of the 15,000 species living in the marine environment are only found here.1

1.3

The New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2000-2020 is part of the Government’s commitment, as a signatory to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, to maintain and preserve New Zealand’s natural environment, both on and offshore. Aims of the Strategy include:

- stopping the decline in New Zealand’s biodiversity and restoring the remaining natural habitats; and

- maintaining the genetic resources of introduced species that are important for economic, biological, and cultural reasons by conserving their genetic diversity.

1.4

In 2005, the Government released Marine Protected Areas: Policy and Implementation Plan (the MPA policy). The MPA policy was to be led by the Ministry of Fisheries, which is now part of the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), and the Department of Conservation (DOC). The MPA policy is currently the government-mandated process for creating marine protected areas (whether in the form of marine reserves or areas where certain activities are regulated or prohibited). This was followed up with the Marine Protected Areas: Classification, protection standard and implementation guidelines in 2008. The aim of the MPA policy is to protect “marine biodiversity by establishing a network of [marine protected areas] that is comprehensive and representative of New Zealand’s marine habitats and ecosystems.”2

1.5

We looked at two different processes that resulted in recommendations for establishing marine protection. Although only one process started with the formal goal of creating a marine protected area, both had the objective of protecting the marine environment and both resulted in recommendations for the Government to establish marine protected areas off New Zealand’s coastline. We looked at whether each process was transparent, inclusive, and informed and what lessons could be learned from them.

Why we chose this audit

1.6

New Zealand has 44 marine reserves. The first of these was established in 1975 at Goat Island, north of Auckland. Since then, proposals for establishing new marine reserves have been infrequent. Only 0.4% of the mainland territorial sea has marine reserves.

1.7

When a decision is made to accept a marine reserve proposal, it effectively prioritises access to and the use of a particular body of water. As a result, each new proposal has the potential to affect a broad range of interests and values. This can lead to tensions between a desire to protect New Zealand’s biodiversity and the perceived effect that this will have on existing rights and values. Getting the process of creating marine protected areas right is important, particularly when establishing marine reserves.

1.8

Previous attempts to establish marine reserves have at times been fraught. In some instances, these attempts have led to legal cases and judicial reviews. For example, the original application for the Akaroa Marine Reserve was publicly notified in 1996. It got to the High Court in 2012 and the marine reserve was finally approved in 2013.

The focus of our audit

1.9

Our audit looked at the development of marine reserve proposals. There are three ways in which a marine reserve proposal can be established:

- using Marine Protection Planning Forums (under the MPA policy);

- through the statutory processes under the Marine Reserves Act 1971; and

- through special legislation.

1.10

We looked at two processes that resulted in recommendations to create marine reserves:

- the “MPA policy process”, which was used by the South-East Coast Marine Forum (the South-East Forum); and

- a “community-led process”, which led to the creation of special legislation, was used by Te Korowai o Te Tai ō Marokura, the Kaikōura Coastal Marine Guardians (Te Korowai).

1.11

We looked at whether the processes were transparent, inclusive, and well informed. By examining how inclusive, transparent, and well informed the processes were, we wanted to identify lessons that could be applied to support the establishment of other marine reserves and marine protection. These three principles are part of the MPA policy.

1.12

We did not assess the biodiversity outcomes that were achieved or likely to be achieved by the two processes.

How marine reserves are established

1.13

The MPA policy is the government-mandated process for creating marine reserves. Its aim is to create marine biodiversity protection. The MPA policy provides the framework for creating a process that is designed to be inclusive and transparent, with decisions about marine protection based on the best available information. It was also designed to minimise the effects of changes on existing users of a marine area.

1.14

A set of implementation guidelines are provided to assist the process for proposing marine protected areas as defined by the MPA policy. These implementation guidelines also define the protection standard that a marine protected area must meet, but not at the expense of biodiversity protection.

1.15

Marine protected areas that are established through marine planning processes must meet the protection standard of the MPA policy. There are different tools for establishing marine protection. Two of these tools, called “Type 1” and “Type 2” marine protected areas, meet the protection standard. Type 1 marine protected areas are marine reserves with the highest level of marine protection and are normally established under the Marine Reserves Act. Type 2 marine protected areas are protected areas established outside of the Marine Reserves Act, and are intended to provide enough protection from the adverse effects of fishing to meet the Marine Protected Area Protection Standard.

1.16

Under the Marine Reserves Act, marine reserves can be proposed to the Director-General of Conservation by community groups, or through institutions with a science or conservation focus, such as various environmental non-governmental organisations. The Director-General can also make an application for a marine reserve.

1.17

Marine reserves can also be formed through special legislation. This is when legislation is created to provide particular solutions for marine protection. Special legislation is usually used to provide support to local or regional planned efforts that have come up with marine management plans. It can address the challenge of implementing a range of proposals and initiatives at the same time.

The Marine Reserves Act 1971

1.18

“The main aim of a marine reserve is to create an area free from alterations to marine habitats and life, providing a useful comparison for scientists to study.” Under the Marine Reserves Act, marine reserves may be established in areas with distinctive or unique marine life, or where continued preservation is in the national interest.

1.19

DOC is responsible for administering the Marine Reserves Act through both statutory and non-statutory processes. The non-statutory process involves defining the objectives and forming a team, initial consultation with interest and user groups, site survey and investigation, preparing and releasing a draft proposal for public comment, and preparing a formal application.

1.20

The statutory process involves making a formal application to the Director-General of Conservation for an Order in Council to declare a marine reserve. The applicant then notifies the public of the application. The public can object to the proposed marine reserve in writing to the Director-General, which the applicant can respond to. The Director-General then presents the application, objections, and any responses to objections to the Minister of Conservation.

1.21

The Minister of Conservation decides whether any objection should be upheld. If none are upheld, the Minister decides whether the proposed marine reserve will be in the best interests of scientific study and will benefit the public. The Minister will also consider if it is expedient to declare a marine reserve. If the Minister concludes yes to these requirements, they will seek agreement from the Minister of Fisheries and the Minister of Transport and, if required, the relevant council. The Minister then makes a recommendation to the Governor-General for the Order in Council to declare the marine reserve.

The processes we looked at

The MPA policy process

1.22

The South-East Forum was a Marine Protection Planning Forum that operated under the direction of the MPA policy and the implementation guidelines. It was led by DOC and supported by MPI. In 2014, the South-East Forum was appointed by the Minister of Conservation and the Minister of Fisheries.

1.23

The South-East Forum was to recommend which sites on the south-east coast of the South Island should be considered for marine protection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The region covered by the South-East Marine Protection Forum

This figure shows that part of the south-east coast of the South Island that was the area under consideration by the South-East Forum for marine protection.

Source: Adapted from South-East Marine Protection Forum (February 2018), Recommendations to the Minister of Conservation and the Minister of Fisheries: Recommendations towards implementation of the Marine Protected, Areas Policy on the South Island’s south-east coast of New Zealand, Wellington, page 35.

1.24

The South-East Forum included 16 people3 who were appointed to represent the views and values of the different groups with interests in the area. They represented:

- tāngata whenua;

- commercial and recreational fishing;

- the environment, science, and tourism sectors; and

- the local community.

1.25

There was also an independent chairperson.

1.26

The South-East Forum was supported by a governance group with members from DOC, MPI, and Ngāi Tahu.

1.27

DOC provided the South-East Forum with financial contributions, governance members, project staff, and technical experts. MPI provided governance members and project staff.

1.28

The South-East Forum proposed two options for networks of marine protected areas, called “Network 1” and “Network 2” (see the Appendix). Ministers have considered joint advice from DOC and MPI and intend to consult on progressing Network 1 in its entirety, noting that amendments might be made based on the outcomes of public consultation and assessments against relevant statutory requirements.

The community-led process

1.29

Te Korowai are a group of community members who, from the initiative of Ngāti Kuri of Ngāi Tahu and with the support of government agencies, prepared a marine strategy for the Kaikōura coast.

1.30

The Kaikōura coast has many unique marine features, such as the biologically rich undersea Kaikōura Canyon. It is also home to several types of marine mammals, including New Zealand’s only population of resident sperm whales.

1.31

Te Korowai was formed with a shared vision to create a more sustainable marine environment and included people from local groups directly involved with the coastal marine area. DOC provided financial support and technical experts. The group was self-governed.

1.32

Previous attempts had been made to create a marine reserve off the coast of Kaikōura, including one from the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand (Forest and Bird). Forest and Bird applied to the then Minister of Conservation for a marine reserve on the Kaikōura peninsula, but the application did not proceed. However, in recognition of the importance of the marine environment, the Minister of Conservation invited Ngāti Kuri to plan formally for the future of the Kaikōura marine environment.

1.33

Funding and support came from a range of sources, including DOC, Kaikōura District Council, Environment Canterbury, the Encounter Foundation, Solution-Multipliers NZ Limited, Canterbury Community Trust, Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura, Ngāi Tahu Communication, Takahanga Marae, the Lobster Inn, the Ministry for the Environment, and MPI. Members of Te Korowai donated much of their time and some also made financial donations.

1.34

The strategy was not prepared under the MPA Policy, and the Minister of Conservation specifically excluded Kaikōura from the national process. However, Te Korowai took the MPA policy’s practice guidance into account.

1.35

In 2008, Te Korowai published a characterisation report on the environment of the Kaikōura coast, followed by the Kaikōura Marine Strategy. The strategy proposes several marine protection and fisheries mechanisms to manage coastal and marine resources. The Government has implemented the main elements of this strategy through the Kaikōura (Te Tai ō Marokura) Marine Management Act 2014, which came into force in August 2014.

Figure 2

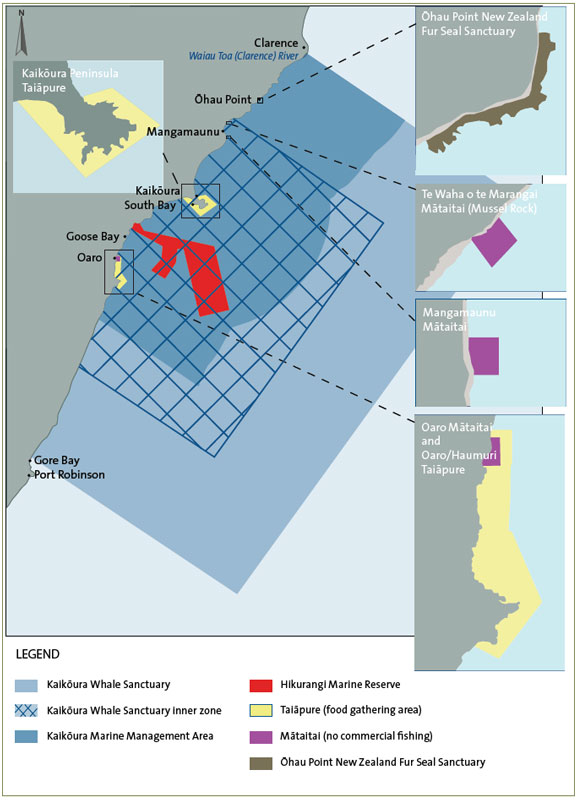

The Kaikōura Marine Management Area

This figure indicates the extent of the Kaikōura Marine Management Area, showing the Kaikōura Whale Sanctuary, the Hikurangi Marine Reserve, two taiāpure (food-gathering areas), three mātatai (no commercial fishing) reserves, and the Ōhau Point New Zealand Fur Seal Sanctuary.

Source: Adapted from www.howtokit.org.nz.

1.36

The Kaikōura (Te Tai ō Marokura) Marine Management Act 2014 established several marine protection and sustainable fisheries measures (see Figure 2).

These include:

- Hikurangi Marine Reserve, covering the Kaikōura Canyon area and connecting to the coast south of the Kaikōura township;

- Te Rohe o Te Whānau Puha/Kaikōura Whale Sanctuary;

- Ōhau Point New Zealand Fur Seal Sanctuary;

- two taiāpure – local fisheries around the Kaikōura Peninsula that provide traditional food-gathering areas; and

- three mātaitai reserves where commercial fishing is prohibited.

1.37

It also established an advisory committee called the Kaikōura Marine Guardians to advise Ministers and those exercising statutory powers. The Kaikōura Marine Guardians represented Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and the Kaikōura community, as well as biosecurity, conservation, education, environment, fishing, marine science, and tourism interests.

How we carried out our audit

1.38

To carry out our audit, we:

- interviewed staff from DOC and MPI, including staff who work on marine strategy and who made up the governance group members of the South-East Forum;

- interviewed members of the South-East Forum and Te Korowai and the support staff who directly worked with them; and

- examined documents related to the processes.

1: For more information on New Zealand’s marine environment, see www.doc.govt.nz.

2: Department of Conservation (2005), Marine Protected Areas: Policy and Implementation Plan, at www.doc.govt.nz, page 6.

3: The 16 people included alternate members for Ngāi Tahu.